Praya dubia

The Praya dubia, or giant siphonophore, is an invertebrate which lives in the deep sea at 700 m (2,300 ft) to 1,000 m (3,300 ft) below sea level. It has been found off the coasts around the world, from Iceland in the North Atlantic, to Chile in the South Pacific.[1]

| Praya dubia | |

|---|---|

| |

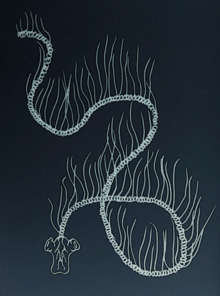

| Illustration of Praya dubia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Cnidaria |

| Class: | Hydrozoa |

| Order: | Siphonophorae |

| Family: | Prayidae |

| Genus: | Praya |

| Species: | P. dubia |

| Binomial name | |

| Praya dubia | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Praya dubia is a member of the order Siphonophorae within the class Hydrozoa. With a body length of up to 50 m (160 ft), it is the second-longest sea organism after the bootlace worm. Its length also rivals the blue whale, the sea’s largest mammal, although Praya dubia is as thin as a broomstick.[2][3]

A siphonophore is not a single, multi-cellular organism, but a colony of tiny biological components called zooids, each having evolved with a specific function. Zooids cannot survive on their own,[4] relying on symbiosis in order for a complete Praya dubia specimen to survive.

Description

Praya dubia zooids arrange themselves in a long stalk—usually whitish and transparent (though other colours have been seen[5])—known as a physonect colony.[6] The larger end features a transparent, dome-like float known as a pneumatophore,[7] filled with gas which provides buoyancy, allowing the organism to remain at its preferred ocean depth. Next to it are the nectophore,[8] powerful medusae which pulsate in rhythmic coordination which propel Praya dubia through ocean waters.[9] Together, the array is known as the nectosome.

Beneath the nectosome is the siphosome which extends to the far end of Praya dubia, containing several types of specialized zooids in repeating patterns.[6] Some have a long tentacle used for catching and immobilizing food and distributing their digested nutrients to the rest of the colony. Other zooids known as palpons, or dactylozooids, appear to contain an excretory system that may also assist in defense, though little is known about their precise function in Praya dubia.[10] Transparent bracts (also called hydrophyllia), are leaf-shaped organs generally thought to be another type of zooid which covers and forces other zooids to contract in times of danger.

Due to their hydrostatic skeleton being held together by water pressure above 46 MPa (460 bar), these animals burst when required to the surface.[11] The remains of Praya dubia dredged up in fishing nets resemble a blob of gelatin, which prevented their identification as a unique creature until the 19th century. In 1987, Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute observed living Praya dubia during a systematic study of a water column, the animal’s natural habitat, in Monterey Bay.[12][13][14]

Behavior

Praya dubia is an active swimmer that attracts its prey with bright blue bioluminescent light.[15] When it finds itself in a region abundant with food, it holds its position and deploys a curtain of tentacles covered with nematocysts which produce a powerful, toxic sting that can paralyze or kill prey that happen to bump into it.[16] Praya dubia’s diet includes gelatinous sea life, small crustaceans, and possibly small fish and fish larvae.[17] It has no known predators.

A Praya dubia specimen, filmed in its native habitat, was featured in Episode 2 of the David Attenborough television series Blue Planet II, produced for the BBC.

References

- "http://iobis.org/explore/#/taxon/497295". iobis.org. Retrieved 2018-01-30. External link in

|title=(help) - "Beauty and the deep". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. Retrieved 2018-01-30.

- "Giant siphonophore, Deep Sea, Invertebrates, Praya sp at the Monterey Bay Aquarium". montereybayaquarium.org. Retrieved 2018-01-30.

- The Deep; the University of Chicago Press, London (2007)

- "What Eats What: A Landlubber's Guide to Deep Sea Dining". nytimes.com. Retrieved 2017-12-19.

- "Siphosome - Biology-Online Dictionary". biology-online.org. Retrieved 2018-01-30.

- "Pneumatophore - Biology-Online Dictionary". biology-online.org. Retrieved 2018-01-30.

- "Nectophore - Biology-Online Dictionary". biology-online.org. Retrieved 2018-01-30.

- "Medusa - Biology-Online Dictionary". biology-online.org. Retrieved 2018-01-30.

- "Dactylozooids". The Free Dictionary.

- "Giant siphonophore". Archived from the original on 1999-11-28. Retrieved 2020-05-10.

- Praya dubia, at the Animal Diversity Web Archived 2008-04-09 at the Wayback Machine

- "Prayid siphonophores". lifesci.ucsb.edu. Retrieved 2018-01-29.

- "The Deep Next Door | Ecology Center". ecologycenter.org. Retrieved 2018-01-29.

- "The Bioluminescence Web Page". biolum.eemb.ucsb.edu. Retrieved 2018-01-29.

- "Siphonophores". siphonophores.org. Retrieved 2018-01-29.

- "Giant siphonophore, Deep Sea, Invertebrates, Praya sp at the Monterey Bay Aquarium". montereybayaquarium.org. Retrieved 2018-01-29.

External links

- Giant Siphonophore Sighting. YouTube, 22 May 2015, by E/V Nautilus during the 2015 ECOGIG dives in the Gulf of Mexico, Accessed 28, January 2018..

- Deep sea siphonophore off Roatán Honduras - 2300 feet, YouTube, 10 June 2013, Roatán Institute of Deepsea Exploration, Accessed 28, January 2018.

- Praya dubia Distribution Map at Ocean Biogeographic Information System

- Praya dubia Habitat at Encyclopedia of Life