Sinking of SS Princess Alice

SS Princess Alice, formerly PS Bute, was a passenger paddle steamer that sank on 3 September 1878 after a collision with the collier Bywell Castle on the River Thames. Between 600 and 700 people died, all from Princess Alice, the greatest loss of life of any British inland waterway shipping accident. No passenger list or headcount was made, so the exact figure of those who died has never been known.

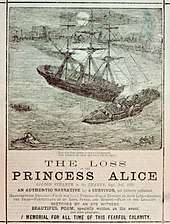

Artist's impression of the collision | |

| Date | 3 September 1878 |

|---|---|

| Time | Between 7:20 pm and 7:40 pm |

| Location | Gallions Reach, River Thames |

| Cause | Collision |

| Casualties | |

| 600 to 700 dead | |

Built in Greenock, Scotland, in 1865, Princess Alice was employed for two years in Scotland before being purchased by the Waterman's Steam Packet Co to carry passengers on the Thames. By 1878 she was owned by the London Steamboat Co and was captained by William R. H. Grinstead; the ship carried passengers on a stopping service from Swan Pier, near London Bridge, downstream to Sheerness, Kent, and back. On her homeward journey, at an hour after sunset on 3 September 1878, she passed Tripcock Point and entered Gallions Reach. She took the wrong sailing line and was hit by Bywell Castle; the point of the collision was the area of the Thames where 75 million imperial gallons (340,000 m3) of London's raw sewage had just been released. Princess Alice broke into three parts and sank quickly; her passengers drowned in the heavily polluted waters.

Grinstead died in the incident, so the subsequent investigations never established which course he thought he was supposed to take. The jury in the coroner's inquest considered both vessels at fault, but more blame was put on the collier; the inquiry run by the Board of Trade found that the Princess Alice had not followed the correct path and her captain was culpable. In the aftermath of the sinking, changes were made to the release and treatment of sewage, and it was transported to, and released into, the sea. The Marine Police Force—the branch of the Metropolitan Police that had responsibility for policing the Thames—were provided with steam launches, after the rowing boats used up to that point had proved insufficient. Five years after the collision Bywell Castle sank in the Bay of Biscay with the loss of all 40 crew.

Background

SS Princess Alice

Caird & Company of Greenock, Scotland, launched the passenger paddle steamer Bute on 29 March 1865.[1][2] She entered service on 1 July 1865.[3] The ship was 219.4 ft (66.9 m) long and 20.2 ft (6.2 m) at the beam, and measured 432 gross registered tons.[4] Bute had been built for the Wemyss Bay Railway Company, for whom she carried passengers between Wemyss Bay and Rothesay. In 1867 she was sold to the Waterman's Steam Packet Co. to travel on the River Thames; the company renamed the vessel Princess Alice, after Queen Victoria's third child. In 1870 she was sold to the Woolwich Steam Packet Company and was operated as an excursion steamer; the company later changed its name to the London Steamboat Company.[5][6][7][8] In 1873 the ship carried Naser al-Din Shah Qajar, the Shah of Persia, up the Thames to Greenwich, and became known to many locals as "The Shah's boat".[9]

When Princess Alice was acquired by the Woolwich Steam Packet Company, the company made several alterations to the ship, including the installation of new boilers and making the five bulkheads watertight. The vessel had been inspected and was passed as safe by the Board of Trade.[5][10] In 1878 another survey by the Board of Trade allowed the ship to carry a maximum of 936 passengers between London and Gravesend in calm water.[6]

SS Bywell Castle

The collier SS Bywell Castle was built in Newcastle in 1870 and was owned by Messrs Hall of Newcastle. Her gross registered tonnage was 1376, she was 254.2 ft (77.5 m) long and 32 ft (9.8 m) at the beam; her depth of hold was 19 ft (5.8 m).[6][11][12] The master was Captain Thomas Harrison.[13]

3 September 1878

On 3 September 1878 Princess Alice was making what was billed as a "Moonlight Trip" from Swan Pier, near London Bridge, downstream to Sheerness, Kent, and back. During the journey she called at Blackwall, North Woolwich and Rosherville Gardens; many of the Londoners on board were travelling to Rosherville to visit the pleasure gardens that had been built 40 years before. As the London Steamboat Co. owned several ships, passengers could use their tickets interchangeably on the day, stopping off to travel on or back on different vessels if they wanted; for tickets from Swan Pier to Rosherville, the cost was two shillings.[14][15]

Princess Alice left Rosherville at about 6:30 pm on her return to Swan Pier; she was carrying close to her full capacity of passengers, although no lists were kept, and the exact number of people on board is unknown.[16][17] The master of Princess Alice, 47-year-old Captain William Grinstead, allowed his helmsman to stay at Gravesend, and replaced him with a passenger, a seaman named John Ayers. Ayers had little experience of the Thames, or of helming a craft such as Princess Alice.[15] Between 7:20 pm and 7:40 pm, Princess Alice had passed Tripcock Point, entered Gallions Reach and come within sight of the North Woolwich Pier—where many passengers were to disembark—when Bywell Castle was sighted.[14][18] Bywell Castle usually carried coal to Africa, but had just been repainted at a dry dock. She was due to sail up to Newcastle to pick up coal bound for Alexandria, Egypt. Harrison was unfamiliar with the conditions, so employed Christopher Dix, an experienced Thames river pilot, though he was not obliged to do so.[13][19][lower-alpha 1] As Bywell Castle had a raised forecastle, Dix did not have a clear view in front of him, so a seaman was placed on lookout.[20]

On leaving Millwall, Bywell Castle proceeded down river at five knots; she kept roughly to the middle of the river, except where other craft were in her way. Approaching Gallions Reach, Dix saw Princess Alice's red port light approaching on a course to pass starboard of them.[21] Grinstead, travelling up the river against the tide, followed the normal watermen's practice of seeking the slack water on the south side of the river.[22][lower-alpha 2] He altered the ship's course, bringing her into the path of Bywell Castle. Seeing the imminent collision, Grinstead shouted to the larger vessel "Where are you coming to! Good God! Where are you coming to!"[24][25][lower-alpha 3] Although Dix tried to manoeuvre his vessel out of a collision course, and ordered the engines to be put into "reverse full speed", it was too late. Princess Alice was struck on the starboard side just in front of the paddle box at an angle of 13 degrees; she split in two and sank within four minutes—her boilers separating from the structure as it sank.[27]

The crew of Bywell Castle dropped ropes from their deck for the passengers of Princess Alice to climb; they also threw anything that would float into the water for people to hold.[28] Other crew from Bywell Castle launched their lifeboat and rescued 14 people, and crews from boats moored nearby did the same. Residents from both banks of the Thames, particularly the boatmen of local factories, launched vessels to rescue who they could.[29][30] Many of the passengers from Princess Alice were unable to swim; the long heavy dresses worn by women also hindered their efforts to stay afloat.[31] Princess Alice's sister ship, Duke of Teck, was steaming ten minutes behind her; she arrived too late to rescue anyone left in the water.[32] Only two people who had been below decks or in the saloon survived the collision;[33] a diver who later examined the saloon reported that the passengers were jammed together in the doorways, mostly still upright.[34]

About 130 people were rescued from the collision, but several died later from ingesting the water.[14] Princess Alice sank at the point where London's sewage pumping stations were sited. The twice-daily release of 75 million imperial gallons (340,000 m3) of raw sewage from the sewer outfalls Abbey Mills, at Barking, and the Crossness Pumping Station had occurred one hour before the collision.[35] In a letter to The Times shortly after the collision, a chemist described the outflow as:

Two continuous columns of decomposed fermenting sewage, hissing like soda-water with baneful gases, so black that the water is stained for miles and discharging a corrupt charnel-house odour, that will be remembered by all ... as being particularly depressing and sickening.[36]

The water was also polluted by the untreated output from Beckton Gas Works, and several local chemical factories.[37] Adding to the foulness of the water, a fire in Thames Street earlier that day had resulted in oil and petroleum entering the river.[35]

Bywell Castle moored at Deptford to await the action of the authorities and the inquest. That night Harrison and Belding, the first mate, wrote the ship's log to describe the event:

At 6:30 left the West Dock, Millwall, in charge of Mr Dicks, [sic] pilot; proceeding slowly, the master and pilot being on the upper bridge ... Light air and weather little hazy. At 7:45 pm proceeding at half speed down Gallions Reach. Being about centre of the Reach, observed an excursion steamer coming up Barking Reach, showing her red and masthead lights, when we ported our helm to keep over towards Tripcock Point. As the vessel neared, observed that the other steamer had ported, and immediately afterwards saw that she had starboarded and was trying to cross our bows, showing her green light close under the port bow. Seeing collision inevitable, stopped our engines and reversed full speed, when the two vessels collided, the bow of Bywell Castle cutting into the other steamer, which was crowded with passengers, with a dreadful crash. Took immediate means for saving life by hauling up over the bows several men of the passengers, throwing rope's-ends over all round the ship, throwing over four lifebuoys, a hold ladder and several planks, and getting out three boats, keeping the whistle blowing loudly all the time for assistance, which was rendered by several boats from shore and a boat from a passing steamer. The excursion steamer, which turned out to be Princess Alice, turning over and sinking under the bows. Succeeded in rescuing a great many passengers and anchored for the night. About 8:30 pm the steamer Duke of Teck came alongside and took off such passengers as had not been taken on shore in the boats.[38]

Aftermath

Recovery of the dead

News of the sinking was telegraphed back to the centre of London, and soon filtered through to those waiting at Swan Pier for the steamer's return. Relatives made their way to the London Steamboat offices near Blackfriars to wait for more news; many took the train from London Bridge to Woolwich.[40] The crowds grew during the night and into the following day, as both relatives and sightseers travelled to Woolwich; additional police were drafted in to help control the crowds, and deal with the remains that were being landed.[41] Reports came in of corpses being washed up as far upstream as Limehouse and down to Erith.[14][42] When bodies were landed, they were stored locally for identification, rather than centrally, although most ended up at Woolwich Dockyard. Relatives had to travel between several locations on both sides of the Thames to search for missing family members.[43][44] Local watermen were hired for £2 a day to search for bodies; they were paid a minimum of five shillings for each one they recovered, which sometimes led to fights over the corpses.[45] One of those picked up was that of Grinstead, Princess Alice's captain.[46]

Because of the pollution from the sewage and local industrial output, the bodies from the Thames were covered with slime, which was found difficult to clean off; the corpses began to rot at a faster pace than normal, and many of the corpses were unusually bloated. Victims' clothing also began to rot quickly and was discoloured after immersion in the polluted water. Sixteen of those who survived died within two weeks, and several others were ill.[35][47]

Inquest

On 4 September Charles Carttar, the coroner for West Kent, opened the inquest for his region. That day he took the jury to view the corpses at Woolwich Town Hall and Woolwich Pier. There were more bodies on the northern bank, but this lay outside his jurisdiction.[48] Charles Lewis, the coroner for South Essex, visited the Board of Trade and the Home Office to try to have the remains in his jurisdiction moved to Woolwich to allow one inquest that could cover all the victims and hear the evidence in only one location, but the law meant that the deceased could not be moved until the inquest had been opened and adjourned.[49] Instead, he opened his inquest to formally identify the bodies under his authority, then adjourned proceedings until after Carttar's case had come to a conclusion. He issued burial orders, and the remains were then transferred to Woolwich.[50][51]

_beached_after_being_cut_in_two_in_a_collision_(1878).jpg)

During low tide, part of Princess Alice's rail could be seen above the waterline. Plans to raise the ship began on 5 September with a diver examining the wreckage. He found the vessel had broken into three sections—the fore, aft and boilers. He reported back that there were still several bodies on board.[52] Work began the following day to raise the larger fore section, which was 27 metres (90 ft) long. This was beached at low tide—2:00 am on 7 September—at Woolwich; while she was being pulled ashore, Bywell Castle steamed past, leaving London, but without her captain, who remained.[53][54] The following day large crowds visited Woolwich again to view the raised section of Princess Alice. Fights broke out in places for the best vantage point, and people rowed up to the wreck to break off souvenirs. An additional 250 policemen were drafted in to help control the crowds.[44][55] That evening, after most of the crowd had gone home, the aft section of the ship was raised and beached next to the bow.[56]

Because of the accelerated rate of decomposition of many of the corpses, the burials of many of those still unidentified took place on 9 September at Woolwich cemetery in a mass grave;[35][37] several thousand people were in attendance.[58][lower-alpha 4] The coffins all carried a police identification number, which was also attached to the clothing and personal items which were retained to aid later identification.[59][60] The same day over 150 private funerals of victims took place.[62]

The first two weeks of Carttar's inquest were given over to the formal identification of the bodies, and visits to the wreck site to examine the remains of Princess Alice.[63] From 16 September the proceedings began to examine the causes of the collision. Carttar began by bemoaning the media coverage of the event, which suggested strongly that Bywell Castle had been in error and should take the blame. He focussed his proceedings on William Beechey, the first body to have been positively identified; Carttar explained to the jury that whatever verdict they reached on Beechey would apply to the other victims.[64][lower-alpha 5] Numerous Thames boatmen appeared as witnesses, all who had been active in the area at the time; their stories of the path taken by Princess Alice differed considerably. Most pleasure craft coming upriver on the Thames would round Tripcock Point and head for the northern bank to take advantage of more favourable currents. Had Princess Alice done that, Bywell Castle would have gone clearly astern of her. Several witnesses stated that once Princess Alice rounded Tripcock Point she had been pushed into the centre of the river by currents; the ship then attempted to turn to port, which would have kept her close to the river's southern bank, but in doing so cut across the bows of Bywell Castle. Several masters of other ships moored nearby who witnessed the collision agreed with this series of events. Princess Alice's chief mate denied that his ship had changed direction.[66]

During the inquest evidence was taken from George Purcell, the stoker on Bywell Castle, who, on the night of the sinking, had told several people that the captain and crew of the ship were drunk. Under oath he changed his claims, and stated that they were sober, and that he had no recollection of claiming that anyone was drunk. Evidence given by other members of Bywell Castle's crew showed it had been Purcell who had been drunk; one crewman said that "Purcell was like the generality of firemen. He was rather the worse for drink, but not so bad that he could not take his watch".[67] Evidence was also taken concerning the state of the Thames at the point the ship sank, and of the construction and stability of Princess Alice.[68] On 14 November, after twelve hours of discussion, the inquest released its verdict; four members of the nineteen-member jury refused to sign the statement.[69] The verdict was:

That the death of the said William Beachey and others was occasioned by drowning in the waters of the River Thames from a collision that occurred after sunset between a steam vessel called the Bywell Castle and a steam vessel called the Princess Alice whereby the Princess Alice was cut in two and sunk, such collision not being wilful; that the Bywell Castle did not take the necessary precaution of easing, stopping and reversing her engines in time and that the Princess Alice contributed to the collision by not stopping and going astern; that all collisions in the opinion of the jury might in future be avoided if proper and stringent rules and regulations were laid down for all steam navigation on the River Thames.

Addenda:

- We consider that the Princess Alice was, on the third of September, seaworthy.

- We think the Princess Alice was not properly and sufficiently manned.

- We think the number of persons onboard the Princess Alice was more than prudent.

- We think the means of saving life onboard the Princess Alice were insufficient for a vessel of her class.[70][lower-alpha 6]

Board of Trade inquiry

Running at the same time as the coroner's inquest was a Board of Trade inquiry. Specific charges were laid against Captain Harrison, two of the crew members of Bywell Castle, and against Long, the first mate of Princess Alice; all had their licences suspended at the start of the hearing.[lower-alpha 7] The Board of Trade proceedings began on 14 October 1878 and continued until 6 November. The board found that Princess Alice had breached Rule 29, Section (d) of the Board of Trade Regulations and the Regulations of the Thames Conservancy Board, 1872. This stated that if two ships are heading towards each other, they should pass on the port side of each other.[lower-alpha 8] As Princess Alice had not followed this procedure, the Board found Princess Alice to blame and that Bywell Castle could not avoid the collision.[74][75]

The company that owned Princess Alice sued the owners of Bywell Castle for £20,000 compensation; the owners of Bywell Castle counter-sued for £2,000.[lower-alpha 9] The case was heard in the Admiralty Division of the High Court of Justice in late 1878. After two weeks, the judgment was that both vessels were to blame for the collision.[77][78]

As no passenger list was kept on Princess Alice—or a record of the number of people on board—it was not possible to calculate the number of people who died: figures vary from 600 to 700.[79][lower-alpha 10] The Times reported that "the coroner believes that there are from 60 to 80 bodies unrecovered from the river. The total number of lives lost must thus have been from 630 to 650".[80] Michael Foley, in his examination of disasters on the Thames, observes that "there was no proof of the final death toll. However, around 640 bodies were eventually recovered".[49] The sinking was the worst inland disaster on water in the UK.[18]

The Mansion House fund for the victims had been opened by the Lord Mayor of London in the aftermath of the sinking;[81] by the time it closed it had raised £35,000, which was distributed among the victims' families.[82][lower-alpha 11]

Consequences and later events

During the 1880s London's Metropolitan Board of Works began to purify the sewage at Crossness and Beckton, rather than dumping the untreated waste into the river,[83] and a series of six sludge boats were ordered to ship effluent into the North Sea for dumping. The first boat commissioned in June 1887 was named Bazalgette—after Joseph Bazalgette, who had rebuilt London's sewer system. The practice of dumping at sea continued until December 1998.[84]

Until Princess Alice sank, the Marine Police Force—the branch of the Metropolitan Police that had responsibility for policing the Thames[lower-alpha 12]—relied on rowing boats for their work. The inquest into the sinking of Princess Alice found that these were insufficient for the requirements of the role, and that they should be replaced by steam launches. The first two launches entered service in the mid 1880s; eight were working by 1898.[85] The Royal Albert Dock, which opened in 1880, helped to separate heavy goods traffic from smaller boats; this and global adoption of emergency signalling lights on boats both helped avoid future tragedies.[14]

After 23,000 people donated to a sixpenny fund, a memorial Celtic cross was erected in Woolwich Cemetery in May 1880. St Mary Magdalene Woolwich, the local parish church, also later installed a stained glass memorial window.[86] In 2008 a National Lottery grant funded the installation of a memorial plaque at Barking Creek to mark the 130th anniversary of the sinking.[87][88]

Princess Alice's owners, the London Steamboat Co, purchased the wreck of the vessel from the Thames Conservancy for £350;[lower-alpha 13] the engines were salvaged and the remainder sent to a ship breaker.[87] The London Steamboat Co were bankrupt within six years, and their successors went into financial difficulties three years after that. According to the historian Jerry White, along with competition from the railways and bus services, the sinking of Princess Alice "had some impact ... in blighting the tidal Thames as a pleasure-ground".[89] Bywell Castle was reported missing on 29 January 1883 sailing between Alexandria and Hull; it carried a cargo of cottonseed and beans. In February 1883 newspapers carried a final report:

It is believed that the steamer Bywell Castle, which ran down the saloon boat Princess Alice, off Woolwich, some years ago, has been lost in the Bay of Biscay, in the gale which proved fatal to the Kenmure Castle. The Bywell Castle carried a crew of 40 men and her cargo consisted of Egyptian produce.[90]

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- Dix had been a river pilot for 34 years. He was employed for £2. 4s 3d to take Bywell Castle from dry dock down to the open waters at Gravesend.[19]

- The normal practice was accepted by mariners; a pamphlet clarifying the rules, with aids to memory in verse, was published as "Rule of the Road", in 1867 by Thomas Gray of the Maritime Department of the Board of Trade.[23]

- Some sources give the call as "Hoy hoy! Where are you coming to!"[26]

- The exact numbers buried on the day differ: Joan Lock, who published a history of the sinking in 2013, states it was 74 (13 in the morning and 61 in the afternoon);[59] The Daily News reported 84 (45 women, 21 men, 12 girls and 6 boys);[60] The Daily Telegraph put the figure at 83 (47 women, 18 men and 18 children);[58] while The Scotsman had the figure at 92.[61]

- Sources provide different spellings for Beechey: Beachey is also shown by some.[65]

- Sunset on 3 September 1878 was 6:42 pm.[71]

- Dix, the pilot on Bywell Castle, held a licence from Trinity House; this was also suspended and the organisation undertook a similar inquiry, after which his licence was returned.[72]

- Rule 29, Section (d) of the Board of Trade Regulations and the Regulations of the Thames Conservancy Board, 1872 states that "If two vessels under steam are meeting end on, or nearly end on, so as to involve risk of collision, the helms of both shall be put to port so that each may pass on the port side of the other."[73]

- £20,000 in 1878 equates to around £1,960,000 in 2020; £2,000 in 1878 equates to around £200,000 in 2020, according to calculations based on the Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[76]

- Sources put the number of dead at "around 640",[18] 650[14][40] and 700.[35]

- £35,000 in 1878 equates to around £3,420,000 in 2020, according to calculations based on the Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[76]

- The Marine Police Force were formed in 1798 to stop looting and corruption connected with trading on the river.[85]

- £350 in 1878 equates to around £30,000 in 2020, according to calculations based on the Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[76]

References

- Deayton 2013, pp. 149–150.

- "Launches". Greenock Telegraph.

- "The Wemyss Bay Railway Company Again". Glasgow Herald.

- Princess Alice, ship 1052614.

- "Loss of the Princess Alice". The Globe.

- Lock 2013, p. 156.

- Thurston 1965, pp. 120–121.

- Foley 2011, p. 69.

- Thurston 1965, pp. 55–56.

- Thurston 1965, p. 121.

- Stark 1878, p. 7.

- Bywell Castle, ship 1063546.

- Lock 2013, p. 11.

- Evans 2018.

- Foley 2011, p. 70.

- "The Collision on the Thames". The Times. 5 September 1878.

- Lock 2013, p. 13.

- Heard 2017.

- Thurston 1965, p. 33.

- Lock 2013, p. 14.

- Thurston 1965, p. 35.

- Dix 1985, p. 96.

- Thurston 1965, pp. 36–37.

- Thurston 1965, p. 23.

- Lock 2013, p. 15.

- "The Collision on the Thames". The Times. 19 September 1878.

- Heard 2017; Thurston 1965, pp. 29–30; Ackroyd 2008, p. 388.

- Lock 2013, p. 16.

- Lock 2013, pp. 19–21.

- Thurston 1965, p. 41.

- Foley 2011, p. 71.

- Lock 2013, p. 22.

- Thurston 1965, p. 25.

- Ackroyd 2008, p. 388.

- Ackroyd 2008, p. 389.

- "A Pharmaceutical Chemist Writes". The Times.

- Guest 1878, p. 56.

- "The Collision on the Thames". Shipping and Mercantile Gazette.

- "The Disaster on the Thames". The Illustrated London News.

- Thurston 1965, pp. 53–54.

- Lock 2013, pp. 25–26.

- Thurston 1965, p. 57.

- Lock 2013, p. 26.

- Thurston 1965, p. 63.

- Foley 2011, p. 76.

- Lock 2013, p. 65.

- Guest 1878, pp. 55–56.

- "The Catastrophe on the Thames". The Manchester Guardian. 5 September 1878.

- Foley 2011, p. 77.

- Thurston 1965, p. 59.

- Lock 2013, p. 33.

- Thurston 1965, pp. 59–60.

- Lock 2013, pp. 57–58.

- Thurston 1965, pp. 60–61.

- "The Catastrophe on the Thames". The Manchester Guardian. 9 September 1878.

- Lock 2013, p. 62.

- "The Great Disaster on the Thames". The Illustrated London News.

- "The Terrible Disaster on the Thames". The Daily Telegraph.

- Lock 2013, pp. 66–67.

- "The Disaster on the Thames". The Daily News.

- "The Steamboat Disaster on the Thames". The Scotsman.

- Lock 2013, p. 68.

- Guest 1878, p. 59.

- Lock 2013, pp. 95–97.

- Lock 2013, p. 220.

- Foley 2011, pp. 81–82.

- Lock 2013, pp. 132–133.

- Thurston 1965, p. 118.

- Lock 2013, pp. 149–149.

- "The Collision on the Thames". The Times. 15 November 1878.

- "London, England, United Kingdom — Sunrise, Sunset and Daylength, September 1878". Time and Date.

- Thurston 1965, p. 151.

- Thurston 1965, p. 152.

- "The Collision on the Thames". The Manchester Guardian. 10 November 1878.

- Lock 2013, p. 162.

- Clark 2019.

- "News". The Manchester Guardian.

- "The Princess Alice: Cross Actions: Judgment". The Manchester Guardian.

- Foley 2011, p. 75.

- "The Collision on the Thames". The Times. 28 November 1878.

- "Summary of News: Domestic". The Manchester Guardian. 6 September 1878.

- Lock 2013, p. 166.

- Dobraszczyk 2014, p. 55.

- Halliday 2013, pp. 106–107.

- "Marine Support Unit". Metropolitan Police.

- Lock 2013, p. 185.

- Foley 2011, p. 78.

- "Your National Lottery: Good Causes". National Lottery.

- White 2016, p. 264.

- "Summary of News: Domestic". The Manchester Guardian. 13 February 1883.

Sources

Books

- Ackroyd, Peter (2008). Thames: Sacred River. London: Vintage. ISBN 978-0-09-942255-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Deayton, Alistair (2013). Directory of Clyde Paddle Steamers. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4456-1487-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dix, Frank (1985). Royal River Highway. Newton Abbot, Devon: David & Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-8005-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dobraszczyk, Paul (2014). London's Sewers. Oxford: Shire Books. ISBN 978-0-7478-1431-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Foley, Michael (2011). "Princess Alice". Disasters on the Thames. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. pp. 69–84. ISBN 978-0-7524-5843-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Guest, Edwin (1878). The Wreck of the Princess Alice. London: Weldon & Co. OCLC 558734677.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Halliday, Stephen (2013). The Great Stink of London: Sir Joseph Bazalgette and the Cleansing of the Victorian Metropolis. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-2580-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lock, Joan (2013). The Princess Alice Disaster. London: Robert Hale. ISBN 978-0-7090-9541-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stark, Malcolm (1878). The Wreck of the Princess Alice, or, The Appalling Thames Disaster, with Loss of About 700 Lives. London: Haughton & Co. OCLC 138281081.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thurston, Gavin (1965). The Great Thames Disaster. London: George Allen & Unwin. OCLC 806176936.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- White, Jerry (2016). London in the Nineteenth Century: 'a Human Awful Wonder of God'. London: The Bodley Head. ISBN 978-1-84792-447-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

News articles

- "The Catastrophe on the Thames". The Manchester Guardian. 5 September 1878. p. 8.

- "The Catastrophe on the Thames". The Manchester Guardian. 9 September 1878. p. 8.

- "The Collision on the Thames". Shipping and Mercantile Gazette. 5 September 1878. p. 6.

- "The Collision on the Thames". The Times. 5 September 1878. p. 9.

- "The Collision on the Thames". The Times. 19 September 1878. p. 8.

- "The Collision on the Thames". The Times. 15 November 1878. p. 9.

- "The Collision on the Thames". The Times. 28 November 1878. p. 9.

- "The Collision on the Thames". The Manchester Guardian. 10 November 1878. p. 7.

- "The Disaster on the Thames". The Illustrated London News. 14 September 1878. pp. 248–249.

- "The Disaster on the Thames". The Daily News. 10 September 1878. p. 2.

- Evans, Alice (3 September 2018). "Princess Alice Disaster: The Thames' 650 Forgotten Dead". BBC News. Retrieved 12 December 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "The Great Disaster on the Thames". The Illustrated London News. 21 September 1878. pp. 272–273.

- "Launches". Greenock Telegraph. 30 March 1865. p. 2.

- "Loss of the Princess Alice". The Globe. 24 October 1878. p. 5.

- "News". The Manchester Guardian. 28 November 1878.

- "A Pharmaceutical Chemist Writes". The Times. 6 September 1878. p. 8.

- "The Princess Alice: Cross Actions: Judgment". The Manchester Guardian. 12 December 1878. p. 8.

- "The Steamboat Disaster on the Thames". The Scotsman. 10 September 1878. p. 5.

- "Summary of News: Domestic". The Manchester Guardian. 6 September 1878. p. 4.

- "Summary of News: Domestic". The Manchester Guardian. 13 February 1883. p. 5.

- "The Terrible Disaster on the Thames". The Daily Telegraph. 10 September 1878. p. 2.

- "The Wemyss Bay Railway Company Again". Glasgow Herald. 6 July 1875. p. 6.

Internet and television media

- "Bywell Castle (1063546)". Miramar Ship Index. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- Clark, Gregory (2019). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 28 January 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Heard, Stawell (9 June 2017). "The Princess Alice Disaster". Royal Museums Greenwich. Archived from the original on 3 January 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "London, England, United Kingdom – Sunrise, Sunset and Daylength, September 1878". Time and Date. Archived from the original on 7 February 2019. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- "Marine Support Unit". Metropolitan Police. Archived from the original on 16 July 2007. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- "Princess Alice (1052614)". Miramar Ship Index. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- "Your National Lottery: Good Causes". National Lottery. Archived from the original on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

External links

- Cameron, Stuart; Asprey, David. "PS Bute". Clydebuilt Database. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2011.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Thames Police Museum record