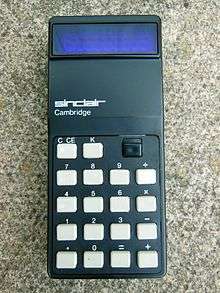

Sinclair Cambridge

The Sinclair Cambridge was a pocket-sized calculator introduced in August 1973 by Sinclair Radionics. It was available both as kit form kit to be assembled by the purchaser, or assembled prior to purchase. The range ultimately comprised seven models, the original "four-function" Cambridge, which carried out the four basic mathematical functions of addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division, being followed by the Cambridge Scientific, Cambridge Memory, two versions of Cambridge Memory %, Cambridge Scientific Programmable and Cambridge Universal.[1]

Close-up of a Cambridge | |

| Manufacturer | Sinclair Radionics |

|---|---|

| Introduced | 1973 |

| Predecessor | Sinclair Executive |

| Cost | GB£43.95 |

| Calculator | |

| Display type | Light-emitting diode |

| Display size | 8 digit |

| Programming | |

| Other | |

| Power supply | 4xAAA batteries |

| Dimensions | 50 by 111 by 28 millimetres (2.0 in × 4.4 in × 1.1 in) |

History

The Cambridge had been preceded by the Sinclair Executive, Sinclair's first pocket calculator, in September 1972. At the time the Executive was smaller and noticeably thinner than any of its competitors, at 56 by 138 by 9 millimetres (2.20 in × 5.43 in × 0.35 in), fitting easily into a shirt pocket.[2]

A major factor in the Cambridge's success was its low price; the Cambridge was launched in August 1973, selling for GB£32.95 (GB£29.95 + VAT) fully assembled or GB£27.45 (GB£24.95 + VAT) as a kit.[3] An extensive manual explained how to calculate functions such as trigonometry, n-th root extraction and compound interest on the device.[1]

Design

The Cambridge was extremely small for a calculator of the time:[1] it weighed less than 3.5 ounces (99 g) and its size was 50 by 111 by 28 millimetres (2.0 in × 4.4 in × 1.1 in). Power was supplied by four AAA batteries.[4]

The use of cheap components was an important contributor to the unit's cost. A common failure mode was with the switch contacts, making it impossible to switch the calculator off. Due to the use of switch contacts made of nickel coated with tin, rather than the gold, an oxide layer would be smeared across the insulating barrier after repeatedly using the switch.[1]

Display

Numbers were displayed on the 8-digit LED display (made by National Semiconductor[5]) in scientific format with a 5-digit mantissa and a 2-digit exponent.[6] The Cambridge used light-emitting diodes for its display. On later scientific variants the power draw for the display required a larger PP3 battery, creating a bulge in the lower rear casing of the appliance.[1]

Variants

A later model, the Sinclair Cambridge Scientific, was developed, and launched in March 1974 at a price of £49.95 (£5 cheaper than its nearest rival from Hewlett-Packard). As the name suggests, it was a development of the Cambridge, using the same case, with the addition of some common scientific functions (sin, cos, tan, etc.).[1]

The other calculators in the range were the Cambridge Memory, Cambridge Memory % (which came in two different versions), Cambridge Programmable (marketed in the United States as the Radio Shack EC-4001), Cambridge Scientific, Cambridge Scientific Programmable and Cambridge Universal.[1]

The Cambridge Programmable (sold in the U.S as the Radio Shack EC-4001[5]) was released in 1975.[7] It lacked accuracy in many of its scientific functions, some yielding only four significant digits. It featured a single memory register and a limit of 36 program steps, along with a conditional jump instruction.[6] The Programmable came with a program library consisting of 4 books, covering general functions, finance & statistics, mathematics, physics & engineering and electronics.[8]

The Cambridge Programmable was superseded by the Sinclair Enterprise, which allowed 80 program steps.[9]

References

Citations

- "Sinclair Cambridge 1973-74". Planet Sinclair. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- "Have you got a Sinclair Executive?". BBC. Archived from the original on 15 April 2003. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- Dale 1985, p. 47

- "Sinclair Cambridge models". vintagecalculators.com. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- "Sinclair Cambridge Programmable Calculator". Computing History. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- "Sinclair Cambridge Programmable". Rskey.org. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- "Sinclair Cambridge Scientific Pocket Calculator New and Boxed". Clive.nl. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- "Sinclair Cambridge Programmable". Voidware.com. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- "Sinclair Enterprise". Voidware.com. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

Sources

- Dale, Rodney (1985). The Sinclair Story. Duckworth. ISBN 9780715619018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)