Sinsharishkun

Sinsharishkun or Sin-shar-ishkun (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: ![]()

| Sinsharishkun | |

|---|---|

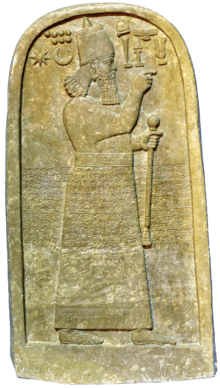

| |

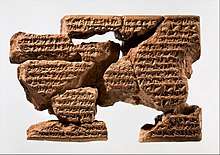

Letter written by Sinsharishkun to his primary enemy, Nabopolassar of Babylon, in which he recognizes him as King of Babylon and pleads to be allowed to retain his kingdom. Now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. | |

| King of the Neo-Assyrian Empire | |

| Reign | 627–612 BC[1] |

| Predecessor | Ashur-etil-ilani |

| Successor | Ashur-uballit II |

| Died | August 612 BC[2] Nineveh |

| Issue | Ashur-uballit II[3] (?) |

| Akkadian | Sîn-šar-iškun Sîn-šarru-iškun |

| Dynasty | Sargonid dynasty |

| Father | Ashurbanipal |

| Mother | Libbali-sharrat |

| Religion | Ancient Mesopotamian religion |

Succeeding his brother in uncertain, but not necessarily violent circumstances, Sinsharishkun was immediately faced by the revolt of one of his brother's chief generals, Sin-shumu-lishir, who attempted to usurp the throne for himself. Though this threat was dealt with relatively quickly, the instability caused by the brief civil war may be what made it possible for another general, Nabopolassar, to rise up and seize power in Babylonia. Sinsharishkun's inability to defeat Nabopolassar, despite repeated attempts over the course of several years, allowed Nabopolassar to consolidate power and form the Neo-Babylonian Empire, restoring Babylonian independence after more than a century of Assyrian rule.

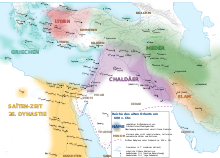

The Neo-Babylonian Empire, and the newly formed Median Empire under King Cyaxares, then invaded the Assyrian heartland. In 614 BC, the Medes captured and sacked Assur, the ceremonial and religious heart of the Assyrian Empire, and in 612 BC their combined armies attacked and razed Nineveh, the Assyrian capital. Sinsharishkun's fate is unknown but it is assumed that he died in the defense of his capital. He was succeeded as king only by Ashur-uballit II, possibly his son, who rallied what remained of the Assyrian army at the city of Harran.

Background and chronology

The period from a few years before the death of King Ashurbanipal to the Fall of Nineveh in 612 BC suffers from a distinct lack of surviving sources. The annals of Ashurbanipal, the primary sources for his reign, go no further than 636 BC.[7] Although Ashurbanipal's final year is often repeated as 627 BC[8][9], this follows an inscription at Harran made by the mother of the Neo-Babylonian king Nabonidus nearly a century later. The final contemporary evidence for Ashurbanipal being alive and reigning as king is a contract from the city of Nippur made in 631 BC.[10] To get the attested lengths of the reigns of his successors to match, most scholars agree that Ashurbanipal either died, abdicated or was deposed in 631 BC.[11] Of the three options, a death in 631 BC is the most accepted.[12] If Ashurbanipal's reign would have ended in 627 BC, the inscriptions of his successors Ashur-etil-ilani and Sinsharishkun in Babylon, covering several years, would have been impossible since the city was seized by the Neo-Babylonian king Nabopolassar in 626 BC to never again fall into Assyrian hands.[13]

Ashurbanipal had named his successor as early as 660 BC, when documents referencing a crown prince (probably Ashur-etil-ilani) were written. He had been the father of at least one son, and probably two, early on in his reign. These early sons were likely Ashur-etil-ilani and Sinsharishkun.[14] Ashur-etil-ilani succeeded Ashurbanipal as king in 631 BC and ruled until his own death in 627 BC. It is frequently assumed, without any supporting evidence, that Sinsharishkun fought with Ashur-etil-ilani for the throne.[15]

Sinsharishkun has sometimes historically and erroneously been known as Esarhaddon II after a letter written by Serua-eterat, a daughter of Sinsharishkun's grandfather King Esarhaddon. The chronology and relations of the royal family were uncertain and Serua-eterat was believed to have been too young to refer to the famous Esarhaddon. The idea of a separate Esarhaddon II as king has been abandoned by Assyriologists since the late 19th century,[16] but the name sometimes appears as a synonym of Sinsharishkun.[17][18]

Reign

Rise to the throne and revolt of Sin-shumu-lishir

In the middle of 627 BC, King Ashurbanipal's son and successor Ashur-etil-ilani died, leading to Ashur-etil-ilani's brother Sinsharishkun ascending to the Assyrian throne.[19] Although it has been suggested by several historians, there is no evidence to prove the idea that Ashur-etil-ilani was deposed in a coup by his brother. Sinsharishkun's inscriptions state that he was selected for the kingship from among several of "his equals" (i.e., his brothers) by the gods.[20]

Also dying at roughly the same time as Ashur-etil-ilani was the vassal king of Babylon, Kandalanu, which led to Sinsharishkun also becoming the ruler of Babylon, as proven by inscriptions by him in southern cities such as Nippur, Uruk, Sippar and Babylon itself.[21] Sinsharishkun's rule of Babylon did not last long, and almost immediately in the wake of him coming to the throne, the general Sin-shumu-lishir rebelled.[19] Sin-shumu-lishir had been a key figure in Assyria during Ashur-etil-ilani's reign, putting down several revolts and possibly being the de facto leader of the country. The rise of another king might have endangered his position and as such led him to revolt and attempt to seize power for himself.[21]

Sin-shumu-lishir successfully seized control of some cities in northern Babylonia, including Nippur and Babylon itself and would rule there for three months before Sinsharishkun defeated him.[19] Though both of them exercised control there, neither Sinsharishkun nor Sin-shumu-lishir officially claimed the title "King of Babylon" (only using "King of Assyria"), meaning that Babylonia experienced an interregnum of sorts.[22]

Rise of Babylon

Some months after Sin-shumu-lishir's revolt, another revolt began in Babylon. A general called Nabopolassar, possibly using the political instability caused by the previous revolt[19] and the ongoing interregnum in the south,[22] assaulted both Nippur and Babylon.[n 1] Nabopolassar's armies took the cities from the garrisons left there by Sinsharishkun but the Assyrian response was swift and in October of 626 BC, the Assyrian army recaptured Nippur and besieged Nabopolassar at Uruk. A simultaneous Assyrian attempt at recapturing Babylon itself, the last ever Assyrian action against the city, was repulsed by Nabopolassar's garrison and the attack at Uruk also failed.[23]

In the aftermath of the failed Assyrian counterattack, Nabopolassar was formally crowned King of Babylon on November 22/23 626 BC, restoring Babylonia as an independent kingdom.[23] In 625–623 BC, Sinsharishkun's forces again attempted to defeat Nabopolassar, campaigning in northern Babylonia. Initially, these campaigns were successful; in 625 BC the Assyrians took the city of Sippar and Nabopolassar's attempted reconquest of Nippur failed. Another of Assyria's vassals, Elam, also stopped paying tribute to Assyria during this time and several Babylonian cities, such as Der, revolted and joined Nabopolassar. Realizing the threat this posed, Sinsharishkun led a massive counterattack himself which saw the successful recapture of Uruk in 623 BC.[24]

Sinsharishkun might have ultimately been victorious had it not been for another revolt, led by an Assyrian general in the empire's western provinces in 622 BC.[24] This general, whose name remains unknown, took advantage of the absence of Sinsharishkun and the Assyrian army to march on Nineveh, met a hastily organized army which surrendered without fighting and successfully seized the Assyrian throne. The surrender of the army indicates that the usurper was an Assyrian and possibly even a member of the royal family, or at least a person that would be acceptable as king.[25] Understandably alarmed by this development, Sinsharishkun abandoned his Babylonian campaign and though he successfully defeated the usurper after a hundred days of civil war, the absence of the Assyrian army saw the Babylonians conquer the last remaining Assyrian outposts in Babylonia in 622–620 BC.[24] The Babylonian siege of Uruk had begun by October 622 BC and though control of the ancient city would shift between Assyria and Babylon, it was firmly in Nabopolassar's hands by 620 BC. Nippur was also conquered in 620 BC and Nabopolassar consolidated his rule over the entirety of Babylonia.[26]

Fall of the Assyrian Empire

The next few years saw repeated Babylonian victories against the Assyrians. By 616 BC, Nabopolassar's armies had reached as far north as the Balikh River. Realizing that the situation was dire, Assyria's ally, Pharaoh Psamtik I of Egypt, marched his troops to aid Sinsharishkun. Psamtik had over the last few years campaigned to establish dominance over the small city-states of the Levant and it was in his interests that Assyria survived as a buffer state between his own empire and those of the Babylonians and Medes in the east.[26] A joint Egyptian-Assyrian campaign to capture the city of Gablinu was undertaken in October of 616 BC, but ended in failure after which the Egyptian allies kept to the west of the Euphrates, only offering limited support.[27]

Following this failure, Assyria quickly collapsed. In March 615 BC, Nabopolassar inflicted a crushing defeat on the Assyrian army at the banks of the Tigris, pushing them back to the Little Zab. Although Nabopolassar's attempt at taking the city of Assur, the ceremonial and religious center of Assyria, in May of that same year failed and he retreated to the city of Takrit, the Assyrians also failed to assault Takrit and put an end to him. After yet another failure, the Assyrian army returned to Assur. In October or November 615 BC, the Medes under King Cyaxares entered Assyria and conquered the region around the city of Arrapha in preparation for a great final campaign against Sinsharishkun.[27]

In July or August of 614 BC, the Medes mounted attacks on the cities of Kalhu and Nineveh and successfully conquered the city of Tarbisu. They then besieged Assur. This siege was successful and the Medes captured the ancient heart of Assyria, plundering it and killing many of its inhabitants. Nabopolassar only arrived at Assur after the plunder had already begun and met with Cyaxares, allying with him and signing an anti-Assyrian pact. Shortly after Assur's fall, Sinsharishkun made his last attempt at a counterattack, rushing to rescue the besieged city of Rahilu, but Nabopolassar's army had retreated before a battle could take place.[2]

In April or May 612 BC, at the start of Nabopolassar's fourteenth year as King of Babylon, the combined Medo-Babylonian army marched on Nineveh. From June to August of that year, they besieged the Assyrian capital and in August the walls were breached, leading to a lengthy and brutal sack.[2] Sinsharishkun's fate is not entirely certain but it is commonly accepted that he died in the defense of Nineveh.[28][29]

Legacy

Succession

With the destructions of Assur in 614 BC and Nineveh in 612 BC, the Assyrian empire had essentially ceased to exist.[30] Sinsharishkun was succeeded by another Assyrian king, Ashur-uballit II, possibly his son and probably the same person as a crown prince mentioned in inscriptions at Nineveh from 626 and 623 BC. Ashur-uballit established himself at Harran in the west.[28] Because Assur had been destroyed, Ashur-uballit could not undergo the traditional coronation of the Assyrian monarchs and could thus not be invested with the kingship by the god Ashur and because of this, inscriptions from his brief reign indicate that he was viewed as the legitimate ruler by his subjects, but still with the title of crown prince and not king. To the Assyrians, Sinsharishkun was the last true king.[31]

Ashur-uballit's rule at Harran lasted just three years and he fled the city when Nabopolassar's army approached in 610 BC.[32][33] An attempt at recapturing Harran carried out with the remnants of the Assyrian army and Egyptian reinforcements in 609 BC failed, after which Ashur-uballit and the Assyrians he commanded disappear from history, never again to be mentioned in Babylonian sources.[34][35]

The Biblical Book of Nahum "prophetically" discusses the Fall of Nineveh, but it is unclear when it was written. It may have been written as early as during Ashurbanipal's Egyptian campaign in the 660s BC, or as late as around the time of Nineveh's actual fall. If it was written around 612 BC, the "king of Assyria" mentioned would be Sinsharishkun.[36]

King of Assyria, your shepherds slumber; your nobles lie down to rest. Your people are scattered on the mountains with no one to gather them.

Reasons for the Fall of Assyria

Although it has been a commonly circulated idea that one of the primary reasons that led to the fall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire was a civil war between Ashur-etil-ilani and Sinsharishkun over the throne which weakened Assyria, there is no contemporary text which suggests that this is true. No inscriptions mention a war or even a dispute between the two brothers. There were revolts at the beginnings of both the reign of Ashur-etil-ilani and Sinsharishkun, but these were minor and dealt with relatively quickly. As such, protracted civil war between contenders to the Assyrian throne was probably not the reason for Assyria's fall.[38]

The primary reason for Assyria's collapse in the reign of Sinsharishkun is more likely to be the failure to resolve the "Babylonian problem" which had plagued Assyrian kings since Assyria first conquered southern Mesopotamia. Despite the many attempts of the kings of the Sargonid dynasty to resolve the constant rebellions in the south in a variety of different ways; Sennacherib's destruction of Babylon and Esarhaddon's restoration of it, rebellions and insurrections remained common. Nabopolassar's revolt was the last in a long line of Babylonian uprisings against the Assyrians and Sinsharishkun's failure to stop it, despite trying for years, doomed his kingdom. The Neo-Babylonian threat, combined with the rise of the Median Empire (Assyria had for many years attempted to stop the formation of a unified Median state through repeated campaigns into Media) culminated in Assyria's destruction.[39]

Titles

From one of his inscriptions commemorating his building projects at Nineveh,[40] Sinsharishkun's titles read as follows:

Sinsharishkun, the great king, the mighty king, king of the Universe, [missing portion] chosen of Ashur and Ninlil, beloved of Marduk and Sarpanitum, dear to the heart of [missing portion], the sure choice of the heart of Nabu and Marduk, favorite of [missing portion], whom Ashur, Ninlil, Bêl, Nabu, Sin, Nin-gal, Ishtar of Nineveh, Ishtar of Arbela in the midst of his companions looked upon with sure favor and called his name for the kingship; whom they named in every metropolis, for the priesthood of every sanctuary and for the rule of all the people, to whose aid they kept coming, like his father and mother, slaying his enemies and bringing low his opponents, [missing portion] whom they created for the rulership of the universe and crowned with the crown of rulership among all [missing portion], for the guidance of his subjects, into whose hand Nabu, guardian of all things, placed a righteous scepter and a just staff [missing portion][40]

In another inscription, commemorating his restoration of a temple, Sinsharishkun incorporates his ancestry:

Sinsharishkun, the great king, the mighty king, king of the Universe, king of Assyria, son of Ashurbanipal, the great king, the mighty king, king of the Universe, king of Assyria, viceroy of Babylon, king of Sumer and Akkad, grandson of Esarhaddon, the great king, the mighty king, king of the Universe, king of Assyria, viceroy of Babylon, king of Sumer and Akkad, great-grandson of Sennacherib, the great king, the mighty king, king of the Universe, king of Assyria, the unrivaled prince, descendant of Sargon, the great king, the mighty king, king of the Universe, king of Assyria, viceroy of Babylon, king of Sumer and Akkad.[41]

Notes

- It is also possible that Nabopolassar was an ally of Sin-shumu-lishir in the previous revolt and merely continued his rebellion, but this theory requires more assumptions without any concrete evidence.[21]

References

- Na’aman 1991, p. 243.

- Lipschits 2005, p. 18.

- Radner 2013.

- Bertin 1891, p. 50.

- Tallqvist 1914, p. 201.

- Frahm 1999, p. 322.

- Ahmed 2018, p. 121.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- Mark 2009.

- Reade 1970, p. 1.

- Reade 1998, p. 263.

- Ahmed 2018, p. 8.

- Na’aman 1991, p. 246.

- Ahmed 2018, pp. 122–123.

- Ahmed 2018, p. 126.

- Johnston 1899, p. 244.

- Woodall 2018, p. 108.

- Myers 1890, p. 51.

- Lipschits 2005, p. 13.

- Na’aman 1991, p. 255.

- Na’aman 1991, p. 256.

- Beaulieu 1997, p. 386.

- Lipschits 2005, p. 14.

- Lipschits 2005, p. 15.

- Na’aman 1991, p. 263.

- Lipschits 2005, p. 16.

- Lipschits 2005, p. 17.

- Yildirim 2017, p. 52.

- Radner 2019, p. 135.

- Lipschits 2005, p. 19.

- Radner 2019, pp. 135–136.

- Rowton 1951, p. 128.

- Bassir 2018, p. 198.

- Radner 2019, p. 141.

- Lipschits 2005, p. 20.

- Walton, Matthews & Chavalas 2012, p. 791.

- Nahum 3:18.

- Na’aman 1991, p. 265.

- Na’aman 1991, p. 266.

- Luckenbill 1927, p. 410.

- Luckenbill 1927, p. 413.

Cited bibliography

- Ahmed, Sami Said (2018). Southern Mesopotamia in the time of Ashurbanipal. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 978-3111033587.

- Bassir, Hussein (2018). "The Egyptian expansion in the near east in the saite period" (PDF). Journal of Historical Archaeology & Anthropological Sciences. 3 (2): 196–200.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (1997). "The Fourth Year of Hostilities in the Land". Baghdader Mitteilungen. 28: 367–394.

- Bertin, G. (1891). "Babylonian Chronology and History". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 5: 1–52.

- Frahm, Eckhart (1999). "Kabale und Liebe: Die königliche Familie am Hof zu Ninive". Von Babylon bis Jerusalem: Die Welt der altorientalischen Königsstädte. Reiss-Museum Mannheim.

- Johnston, Christopher (1899). "A Recent Interpretation of the Letter of an Assyrian Princess". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 20: 244–249. doi:10.2307/592332. JSTOR 592332.

- Lipschits, Oled (2005). The Fall and Rise of Jerusalem: Judah under Babylonian Rule. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1575060958.

- Luckenbill, Daniel David (1927). Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia Volume 2: Historical Records of Assyria From Sargon to the End. University of Chicago Press.

- Myers, P. V. N. (1914). A General History for Colleges and High Schools. Boston: Ginn & Company.

- Na’aman, Nadav (1991). "Chronology and History in the Late Assyrian Empire (631—619 B.C.)". Zeitschrift für Assyriologie. 81: 243–267.

- Radner, Karen (2019). "Last Emperor or Crown Prince Forever? Aššur-uballiṭ II of Assyria according to Archival Sources". State Archives of Assyria Studies. 28: 135–142.

- Reade, J. E. (1970). "The Accession of Sinsharishkun". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 23 (1): 1–9. doi:10.2307/1359277. JSTOR 1359277.

- Reade, J. E. (1998). "Assyrian eponyms, kings and pretenders, 648-605 BC". Orientalia (NOVA Series). 67 (2): 255–265. JSTOR 43076393.

- Rowton, M. B. (1951). "Jeremiah and the Death of Josiah". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 2 (10): 128–130. doi:10.1086/371028.

- Tallqvist, Knut Leonard (1914). Assyrian Personal Names (PDF). Leipzig: August Pries.

- Walton, John H.; Matthews, Victor H.; Chavalas, Mark W. (2012). The IVP Bible Background Commentary: Old Testament. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0830866083.

- Woodall, Chris (2018). Minor Prophets in a Major Key. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1532642180.

- Yildirim, Kemal (2017). "Diplomacy in Neo-Assyrian Empire (1180-609) Diplomats in the Service of Sargon II and Tiglath-Pileser III, Kings of Assyria". International Academic Journal of Development Research. 5 (1): 128–130.

Cited web sources

- "Ashurbanipal". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- Mark, Joshua J. (2009). "Ashurbanipal". Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- "Nahum 3:18". Bible Hub. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- Radner, Karen (2013). "Royal marriage alliances and noble hostages". Assyrian empire builders. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

External links

- Daniel David Luckenbill's Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia Volume 2: Historical Records of Assyria From Sargon to the End, containing translations of Sinsharishkun's inscriptions.

Sinsharishkun Died: August 612 BC | ||

| Preceded by Ashur-etil-ilani |

King of Assyria 627 – 612 BC |

Succeeded by Ashur-uballit II |