Diospyros virginiana

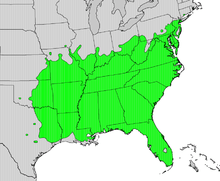

Diospyros virginiana is a persimmon species commonly called the American persimmon,[2] common persimmon,[3] eastern persimmon, simmon, possumwood, possum apples,[4] or sugar plum.[5] It ranges from southern Connecticut/Long Island to Florida, and west to Texas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Iowa. The tree grows wild but has been cultivated for its fruit and wood since prehistoric times by Native Americans.

| Diospyros virginiana | |

|---|---|

| |

| Botanical details of buds, flowers and fruit | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Ericales |

| Family: | Ebenaceae |

| Genus: | Diospyros |

| Species: | D. virginiana |

| Binomial name | |

| Diospyros virginiana | |

| |

| Distribution map of the American persimmon | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

Diospyros mosieri S.F.Blake | |

Diospyros virginiana grows to 20 m (66 ft), in well-drained soil. In summer, this species produces fragrant flowers which are dioecious, so one must have both male and female plants to obtain fruit. Most cultivars are parthenocarpic (setting seedless fruit without pollination). The flowers are pollinated by insects and wind. Fruiting typically begins when the tree is about 6 years old.

The fruit is round or oval and usually orange-yellow, sometimes bluish, and from 2 to 6 cm (3⁄4 to 2 1⁄4 in) in diameter. In the U.S. South and Midwest, the fruits are referred to as simply persimmons or "'simmons", and are popular in desserts and cuisine.

Commercial varieties include the very productive Early Golden, the productive John Rick, Miller, Woolbright and the Ennis, a seedless variety. Another nickname of the American persimmon, 'date-plum' also refers to a persimmon species found in South Asia, Diospyros lotus.

Description

The plant itself is a small tree usually 30 to 80 feet (9 to 24 m) in height, with a short, slender trunk and spreading, often pendulous branches, which form a broad or narrow, round-topped canopy. The roots are thick, fleshy and stoloniferous. This species has a shrubby growth form.[6] This plant has oval entire leaves, and unisexual flowers on short stalks. In the male flowers, which are numerous, the stamens are sixteen in number and arranged in pairs; the female flowers are solitary, with traces of stamens, and a smooth ovary with one ovule in each of the eight cells—the ovary is surmounted by four styles, which are hairy at the base. The fruit-stalk is very short, bearing a subglobose fruit an inch in diameter or a bit larger, of an orange-yellow color, ranging to bluish, and with a sweetish astringent pulp. It is surrounded at the base by the persistent calyx-lobes, which increase in size as the fruit ripens. The astringency renders the fruit somewhat unpalatable, but after it has been subjected to the action of frost, or has become partially rotted or "bletted" like a medlar, its flavor is improved.[7]

- Bark: Dark brown or dark gray, deeply divided into plates whose surface is scaly. Branchlets slender, zigzag, with thick pith or large pith cavity; at first light reddish brown and pubescent. They vary in color from light brown to ashy gray and finally become reddish brown, the bark somewhat broken by longitudinal fissures. Astringent and bitter.

- Wood: Very dark; sapwood yellowish white; heavy, hard, strong and very close grained. Specific gravity, 0.7908; weight of cubic foot, 49.28 lb (22.35 kg). The heartwood is a true ebony. Forestry texts indicate that about a century of growth is required before a tree will produce a commercially viable yield of ebony wood.

- Winter buds: Ovate, acute, one-eighth of an inch long, covered with thick reddish or purple scales. These scales are sometimes persistent at the base of the branchlets.

- Leaves: Alternate, simple, four to six inches (152 mm) long, oval, narrowed or rounded or cordate at base, entire, acute or acuminate. They come out of the bud revolute, thin, pale, reddish green, downy with ciliate margins, when full grown are thick, dark green, shining above, pale and often pubescent beneath. In autumn they sometimes turn orange or scarlet, sometimes fall without change of color. Midrib broad and flat, primary veins opposite and conspicuous. Petioles stout, pubescent, one-half to an inch in length.

- Flowers: May, June, when leaves are half-grown; diœcious or rarely polygamous. Staminate flowers borne in two to three-flowered cymes; the pedicels downy and bearing two minute bracts. Pistillate flowers solitary, usually on separate trees, their pedicels short, recurved, and bearing two bractlets.

- Calyx: Usually four-lobed, accrescent under the fruit.

- Corolla: Greenish yellow or creamy white, tubular, four-lobed; lobes imbricate in bud.

- Stamens: Sixteen, inserted on the corolla, in staminate flowers in two rows. Filaments short, slender, slightly hairy; anthers oblong, introrse, two-celled, cells opening longitudinally. In pistillate flowers the stamens are eight with aborted anthers, rarely these stamens are perfect.

- Pistil: Ovary superior, conical, ultimately eight-celled; styles four, slender, spreading; stigma two-lobed.

- Fruit: A juicy berry containing one to eight seeds, crowned with the remnants of the style and seated in the enlarged calyx; depressed-globular, pale orange color, often red-cheeked; with slight bloom, turning yellowish brown after freezing. Flesh astringent while green, sweet and luscious when ripe.[6]

Distribution

The tree is very common in the South Atlantic and Gulf states, and attains its largest size in the basin of the Mississippi River.[7] Its habitat is southern, it appears along the coast from Connecticut to Florida; west of the Alleghenies it is found in southern Ohio and along through southeastern Iowa and southern Missouri; when it reaches Louisiana, eastern Kansas and Oklahoma it becomes a mighty tree, one hundred fifteen feet high.[6]

Its fossil remains have been found in Miocene rocks of Greenland and Alaska and in Cretaceous formations in Nebraska.[6]

Diospyros virginiana is considered to be an evolutionary anachronism that was consumed by one or more of the Pleistocene megafauna that roamed the North American continent until 10,000 years ago. A 2015 study found that passage of persimmon seeds through the gut of modern elephants increased the rate of seed germination and decreased time to sprouting, which supports the idea that Pleistocene members of the elephant family were the ghost partner who accomplished seed dispersal prior to extinction of the North American members of the elephant family.[8]

Ecology and uses

The fruit is eaten by birds, raccoons, skunks, white-tailed deer, semi-wild hogs, flying squirrels, and opossums.[9]

The peculiar characteristics of its fruit have made the tree well known. This fruit is a globular berry, with variation in the number of seeds, sometimes with eight and sometimes without any. It bears at its apex the remnants of the styles and sits in the enlarged and persistent calyx. It ripens in late autumn, is pale orange with a red cheek, often covered with a slight glaucous bloom. One joke among Southerners is to induce strangers to taste unripe persimmon fruit, as its very astringent bitterness is shocking to those unfamiliar with it. The peculiar astringency of the fruit is due to the presence of a tannin similar to that of cinchona. The seeds were used as buttons during the American Civil War.[10]

The fruit is high in vitamin C. The unripe fruit is extremely astringent. The ripe fruit may be eaten raw, cooked or dried. Molasses can be made from the fruit pulp. A tea can be made from the leaves and the roasted seed is used as a coffee substitute. Other popular uses include desserts such as persimmon pie, persimmon pudding, or persimmon candy.

The fruit is also fermented with hops, cornmeal or wheat bran into a sort of beer[11] or made into brandy. The wood is heavy, strong and very close-grained and used in woodturning.[7]

Cultivation

The tree prefers light, sandy, well-drained soil, but will grow in rich, southern, bottom lands.[6]

The tree is greatly inclined to vary in the character and quality of its fruit, in size this varies from that of a large cherry to a small apple. Some trees in the south produce fruit that is delicious without the action of the frost, while adjoining trees produce fruit that never becomes edible.[6]

It was brought to England before 1629 and is cultivated, but rarely if ever ripens its fruit. It is easily raised from seed and can also be propagated from stolons, which are often produced in great quantity. The tree is hardy in the south of England and in the Channel Islands.[7]

In respect to the power of making heartwood, the persimmon rarely develops any heartwood until it is nearly one hundred years old. This heartwood is extremely close-grained and almost black, resembling ebony (of which it is a true variety).[6][12]

It is a common misconception persimmon fruit needs frost to ripen and soften, called bletting. Some, such as the early-ripening varieties "pieper" and "NC21"(also known as "supersweet"), easily lose astringency and become completely free of it when slightly soft at the touch—these are then very sweet, even in the British climate. On the other hand, some varieties (like the very large fruited "yates", which is a late ripening variety) remain astringent even when the fruit has become completely soft (at least in the British climate). Frost, however, destroys the cells within the fruit, causing it to rot instead of ripen. Only completely ripe and soft fruit can stand some frost; it will then dry and become even sweeter (hence the misconception). The same goes for the Oriental persimmon (Diospyros kaki), where early frost can severely damage a fruit crop.

Toxicity

Ingestion by humans can result in formation of a diospyrobezoar, a condition where indigestible material from the persimmon pulp is retained in the intestines, most commonly in the stomach.[13]

References

- "NatureServe Explorer 2.0 - Diospyros virginiana, Persimmon". explorer.natureserve.org. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- "Diospyros virginiana". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- "Diospyros virginiana". Natural Resources Conservation Service PLANTS Database. USDA.

- Karp, David (2000-11-08). "Know Your Persimmons". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- Phillips, Jan (1979). Wild Edibles of Missouri. Jefferson City, Missouri: Missouri Department of Conservation. p. 40.

- Keeler, Harriet L. (1900). Our Native Trees and How to Identify Them. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 195–199.

-

- Boone, Madison J.; Davis, Charli N.; Klasek, Laura; Del Sol, Jillian F.; Roehm, Katherine; Moran, Matthew D. (2015). "A Test of Potential Pleistocene Mammal Seed Dispersal in Anachronistic Fruits using Extant Ecological and Physiological Analogs". Southeastern Naturalist. 14: 22–32. doi:10.1656/058.014.0109.

- Peattie, Donald Culross (1953). A Natural History of Western Trees. New York: Bonanza Books. p. 682.

- Dodge, David (1886). "Domestic Economy in the Confederacy". The Atlantic Monthly. 58 (August): 229–241.

- "Persimmon Ale". Bloomington Brewing Company. Retrieved 2017-11-07.

- The ebony of commerce is derived from five different tropical species of the genus, two from India and one each from Africa, Malaya and Mauritius. The beautiful variegated coromandel wood is the product of a species found in Ceylon.

- Iwamuro M, Okada H, Matsueda K, Inaba T, Kusumoto C, Imagawa A, Yamamoto K (April 2015). "Review of the diagnosis and management of gastrointestinal bezoars". World J Gastrointest Endosc. 7 (4): 336–45. doi:10.4253/wjge.v7.i4.336. PMC 4400622. PMID 25901212.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Diospyros virginiana. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Diospyros virginiana |

- Native Plant Database profile, Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, University of Texas at Austin

- The Perfectly Pleasing Persimmon (Dan Nickrent)

- Bioimages.vanderbilt.edu: Diospyros virginiana images

- Persimmonpudding.com - dedicated to growing, education, and use of Diospyros virginiana, the Common or American persimmon

- Treetrail.net: Diospyros virginiana (American Persimmon) Native Range Distribution Map