Signals of Belief in Early England

Signals of Belief in Early England: Anglo-Saxon Paganism Revisited is an academic anthology edited by the British archaeologists Martin Carver, Alex Sanmark and Sarah Semple which was first published by Oxbow Books in 2010. Containing nine separate papers produced by various scholars working in the fields of Anglo-Saxon archaeology and Anglo-Saxon history, the book presents a number of new perspectives on Anglo-Saxon paganism and, to a lesser extent, early Anglo-Saxon Christianity. The collection – published in honour of the archaeologist Audrey Meaney – was put together on the basis of a conference on "Paganism and Popular Practice" held at the University of Oxford in 2005.

| |

| Author | Martin Carver, Alex Sanmark and Sarah Semple (editors) |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Anglo-Saxon archaeology Religious studies Pagan studies |

| Publisher | Oxbow Books |

Publication date | 2010 |

| Media type | Print (Paperback) |

| Pages | 212 |

| ISBN | 978-1-84217-395-4 |

Opening with a foreword by Neil Price, the book's first paper, written by Carver, examines how archaeologists can best understand Anglo-Saxon paganism, drawing from the works of Price and David Lewis-Williams in order to do so. The second, written by Semple, looks at how pagan Anglo-Saxons viewed their surrounding landscape, whilst the third, written by Julie Lund, delves into Anglo-Saxon votive depositions into water. The fourth paper, authored by Howard Williams, looks at funerary practices, which is followed by Jenny Walker's study on the religious aspects of the hall.

The sixth paper, produced by Aleks Pluskowski, delves into the roles of animals in Anglo-Saxon belief, while Chris Fern's following paper focuses on the role of the horse. The eighth paper, written by Sanmark, looks at conceptions of ancestors and the soul, while the ninth, co-authored by Sue Content and Howard Williams, looks at the subsequent understandings of Anglo-Saxon pagandom. In the afterword, written by historian Ronald Hutton, the findings of the book are summarised and potential areas of future research highlighted.

The book received a mixed review in Charlotte Behr's review for the journal Anglo-Saxon England, and a positive one from Chris Scull in the British Archaeology magazine. It was praised by others looking at the field of Anglo-Saxon paganism, such as Stephen Pollington.

Background

The origins for Signals of Belief in Early England came from a conference held in 2005 at the University of Oxford; based around the subject of "Paganism and Popular Practice", it had been organised by Sarah Semple and Alex Sanmark, two archaeologists who would go on to edit the volume. The decision to produce a book based on the papers presented at that conference gained a "renewed impetus" after two further academic conferences were held by the Sutton Hoo Society, on the subjects of paganism and Anglo-Saxon halls respectively.[1]

The collection was published in honour of the archaeologist Audrey Meaney, "in appreciation of her studies of Anglo-Saxon paganism."[2] In the foreword, archaeologist Neil Price commented on Meaney and her influential work, noting that most of the published studies that had previously delved into the world of Anglo-Saxon paganism came from her "monumental output", and that it was her "years spent patiently excavating Anglo-Saxon attitudes this collection honours."[3]

Synopsis

Preface

Carver, Sanmark and Semple.[4]

In the book's preface, written by Martin Carver, Alex Sanmark and Sarah Semple, the anthology's three objectives are laid out. The first of these is to establish that Anglo-Saxon paganism consisted of "a set of beliefs that varied from place to place" rather than being a dogmatic religion that was the same across England. The second objective is to show that the beliefs of the pagan Anglo-Saxons, "whether pure reason or intellectual mish-mash, [were] expressed in their material culture". Carrying on from the second, the third objective of the anthology was to show that through archaeology, contemporary scholars can "rediscover" Anglo-Saxon belief.[4]

Summing up their view of Anglo-Saxon paganism, the editors state that it "was not a religion with supraregional rules and institutions but a loose term for a variety of local intellectual world views".[4] They also "extend the same courtesy to Christianity", noting that "Christianisation too hides a multiplicity of locally negotiated positions".[4] Ultimately, the writers noted that neither "paganism nor Christianity are treated here as independent agents, out to confront and better each other. They are sources on which people, local people – the true agents of Anglo-Saxon England – eclectically drew.[4]

Price's "Foreword: Heathen Songs and Devil's Games"

The book's foreword, entitled "Heathen Songs and Devil's Games", was written by the archaeologist Neil Price, then a professor at the University of Aberdeen. Price had previously been involved in the investigation of the pre-Christian religious beliefs of northern Europe, authoring the influential book, The Viking Way: Religion and War in the Later Iron Age of Scandinavia (2002). In his foreword, Price comments positively on Signals of Belief in Early England as a whole, noting that it is "remarkable that the present book represents the first attempt for nearly two decades to present an overall survey of early English beliefs that cannot be firmly situated within a Christian frame."[3] Ultimately, Price writes, Signals of Belief in Early England "simply represents the state of the art, with supporting references to the work on which it builds, and summarises with admirable caution and sensitivity most of what we currently know about the intricate mental world of the pre-Christian English. All future journeys through this difficult terrain must necessarily start here, and they could not have a better guide."[5]

Carver's "Agency, Intellect and the Archaeological Agenda"

In the first paper of the anthology, written by Martin Carver of the University of York, the author opens with a discussion of the work of Neil Price in his book The Viking Way (2002), which explored the existence of female shamans in pre-Christian Scandinavian society.[6] He proceeds to note that the work of Price and other academics has enabled contemporary scholars to understand historical paganism far better than ever before because they are "better equipped in that triad of disciplines"; archaeology, anthropology and history.[7] Carver then goes on to discuss the work of the archaeologist David Lewis-Williams in his book The Mind in the Cave (2002), which Carver argued has "redefined the world of early spirituality for archaeologists". Carver expresses his opinion that both Lewis-Williams' theories and his multidisciplinary approach (using methods drawn from disciplines like anthropology, psychology, art and ethnology) can be employed in order to shed light on the world of Anglo-Saxon paganism.[8] He proceeds to point out several problems facing archaeologists in their study of Anglo-Saxon paganism,[9] before looking at the ideas put forward by the archaeologists Colin Renfrew and Tim Insoll for how to best understand the cognitive aspects of historical religious beliefs.[10]

Martin Carver.[11]

Setting up a "programme for investigating Anglo-Saxon spirituality", Carver argues that those Anglo-Saxonist archaeologists who have focused their research on either the pagan or the Christian periods of Anglo-Saxon history need to interact with one another far more, before stating that the same is true for prehistorians and medievalists; in Carver's opinion, an understanding of the beliefs of the Early Anglo-Saxon period can only be achieved by understanding it as being, in part, a "continuum of prehistory".[11] Moving on to discuss the burial monuments of Anglo-Saxon England and their relations with those found elsewhere in north-western Europe, Carver argues that we can understand more about the beliefs of people at the time by looking at the spread of specific burial styles.[12] He then looks at the assembly sites found in Anglo-Saxon England, arguing that there is sufficient archaeological evidence for specific shrine structures, here drawing parallels with the work of archaeologist Leszek Słupecki in relation to the pagan shrines of Slavic Europe. Going on to reference several excavations in northern Europe, Carver discusses the theory that halls were also used as ritual spaces, and considers whether the same could be true of Anglo-Saxon England.[13]

In the third part of his paper, Carver deals with what he describes as "Christian variants", arguing that in his view, the archaeological evidence implies that "paganism and Christianity do not, in this period, describe homogenous intellectual positions or canons of practice. Pagan ideas and material vocabulary were drawn from a wide reservoir of cosmology and were recomposed as local statements with their own geographical and chronological context. I believe that the same kind of evidence, the evidence of monumentality, provokes us to a similar judgment of Christianity."[14] For this reason, Carver argues, most individuals in 7th-century England were neither clearly Christian or pagan, but adhered to elements of both in a syncretic fashion.[15]

Semple's "In the Open Air"

In the second paper of the anthology, entitled "In the Open Air", Sarah Semple provides an overview of what she refers to as the "pre-Christian sacred landscape". Opening the article, Semple discusses the theoretical trends behind recent Anglo-Saxon scholarship and looks at how these can enlighten our understanding of the Anglo-Saxon landscape; in doing so she argues in favour of an interdisciplinary approach which uses historical sources to back up archaeology, before then arguing for the use of continental European parallels to shed light on the world of Early Mediaeval England. Finally she argues that the landscape archaeology of Anglo-Saxon England has to be seen as an extension of the earlier prehistoric and Romano-British landscape rather than in isolation.[16]

Initially describing "natural places" in the landscape, Semple discusses how the pagan Anglo-Saxons may have understood their surroundings, looking at the manner in which fields and groves were devoted to deities. Proceeding to look at the way in which pre-Christian Anglo-Saxons viewed hilltops, she discusses their association with sites designated as hearg in Old English. Semple then looks at the role of fissures, hollows and pits, highlighting how Anglo-Saxons believed them to be inhabited by monsters and goblins, before examining similar ideas regarding water-places, which were believed to be inhabited by nicor and which also saw some votive depositions occurring in the Early Mediaeval. Discussing votive offerings to such water-places, she then discusses the Anglo-Saxon attitude towards "ancient remains, monuments and ruins", discussing the re-use of prehistoric burial mounds and Roman-period structures. Rounding off her paper, Semple discusses evidence for pagan temples and shrines in the Anglo-Saxon landscape, as well as sacred beams, poles and totems.[17]

Lund's "At the Water's Edge"

The anthology's third paper was produced by Julie Lund, then a Senior Lecturer in archaeology at the University of Oslo in Norway. Entitled "At the Water's Edge", it looked at the relationship between the pre-Christian Anglo-Saxons and watery areas such as rivers and lakes, relying particularly on comparisons from Scandinavia. Opening with a discussion of those votive offerings that had been deposited into water, it goes on to discuss the Early Mediaeval idea that objects, and in particular swords, had personalities, and how this might be related to their ritual deposition. Proceeding to discuss the role of rivers in the Anglo-Saxon cognitive landscape, it examines the archaeological evidence for votive deposits placed into them at this time, noting the wide array of weapons, but also jewellery and tools, which have been found.[18]

Lund moves on to discuss the role of bridges, fords and crossings in both Scandinavian and Anglo-Saxon contexts, arguing that they were significant sites in the latter's cognitive landscape, and that they were often used as the sites for votive offerings. She then discusses the role of lakes, noting that while there is ample evidence for votive deposition in Scandinavian lakes, there is currently none from Anglo-Saxon England. Finally, she looks at Christian attempts to suppress pagan ritual activity at watery places, and the revival which it experienced following the Scandinavian settlement of Britain.[19]

Williams' "At the Funeral"

The fourth paper in Signals of Belief was authored by Howard Williams, then a Professor of Archaeology at the University of Chester. Devoted to evaluating the evidence for pre-Christian Anglo-Saxon burial rites, it begins by explaining the approaches taken to this subject by earlier antiquarians and archaeologists. Moving on, Williams discusses the idea that mortuary practices in the Early Medieval Germanic-speaking world reflected pagan cosmology, eschatology, cosmogony and mythology, and describes those Scandinavian examples where aspects of the burial rituals have been interpreted as being symbolically related to elements of Norse mythology. Williams then discusses the role of cremation as a burial rite in Anglo-Saxon England, arguing that the whole cremation process must be viewed as a series of ritualised events rather than as a singular occurrence. Proceeding to discuss inhumation burials, Williams once more argues that there would have been a series of different ritualised scenes as the corpse was prepared, laid in the grave, and then covered in soil, rather than simply one singular layout of the dead.[20]

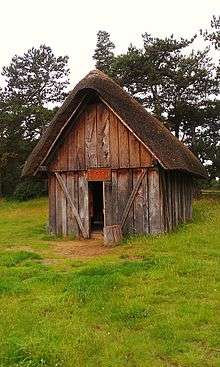

Walker's "In the Hall"

The fifth paper of the anthology, authored by Jenny Walker, a graduate of the University of York's Department of Archaeology, explores the role that the great wooden halls served as "ritual theatre[s]" in Anglo-Saxon paganism, using the Northumbrian site of Yeavering as a case study. Commenting on earlier approaches to understanding the relationship between religious practices and the Early Medieval hall both in England and Scandinavia, she highlights the influence of post-processual archaeology in altering earlier culture-historical perspectives on this subject. Referencing the theories of sociologist Anthony Giddens, Walker maintains that the role of both human agency and ideology in constructing the halls "as a political act" must be taken into account by archaeologists adopting a post-processual approach.

Proceeding to discuss the evidence for three of the halls excavated at Yeavering by archaeologist Brian Hope-Taylor in the early 20th century – buildings A2, D2b and Bab – she then goes on to discuss the archaeological evidence for two Scandinavian examples, Uppåkra in Skana, Sweden, and Borg at Vestvågøy, Norway, both of which show evidence for ritual activity. Concluding her paper, Walker emphasises the diversity in uses that halls in Anglo-Saxon England – and wider Northwestern Europe – had been put in the Early Medieval. Some, she asserts, would have been used for both socio-political and socio-religious activities, while others would have been explicitly reserved for just one of these activities.[21]

Pluskowski's "Animal Magic"

Aleks Pluskowski – an Archaeology Lecturer at the University of Reading – offers the anthology's six paper, an exploration of the role that non-human animals played in pre-Christian Anglo-Saxon religion. Opening with a discussion of the "zoomorphic" symbolism of Early Anglo-Saxon art, he also lists the various different species, both wild and domestic, that the people of Anglo-Saxon England would have been familiar with from their daily lives. Pluskowski then moves on to look at the zoomorphic symbolism found on shields, themselves symbols of adult masculinity in Anglo-Saxon England, before providing a discussion of the idea that animals offered "windows to cosmology", representing symbols of different mythological figures and cosmological places that contemporary scholarship is unaware of, in doing so referencing the work of Stephen Glosecki. Proceeding to examine the symbolic use of animals in Anglo-Saxon warfare, he rounds off this chapter by dealing with both comparisons from continental Europe and Scandinavia and by looking at the influence that Christianity had on re-deploying the symbolism of zoomorphic designs.[22]

Fern's "Horses in Mind"

In his paper, Chris Fern, an independent archaeologist and Research Associate of the University of York, explored the role of the horse in Anglo-Saxon paganism. Remarking that the horse was "a motif with socio-political, heroic and spiritual significance" for the early Anglo-Saxons, he begins with a brief overview of the importance of horses in the preceding prehistoric and Roman periods of British history. Moving on to explore the ceremonial usages of horses in Anglo-Saxon England, he first examines the archaeological evidence for horses who had been cremated or placed in inhumation burials, including those from sites such as the Snape ship burial who had been ritually beheaded. Fern follows this with an examination of horses depicted in Anglo-Saxon art, noting the predominance of motifs featuring either two fighting stallions or a warrior riding a horse, the latter being an image which Fern argues had been adopted from Imperial Rome. He also puts forward the theory that the geometric stamps found imprinted on pots represented horse branding marks.

Proceeding to look at horses featured in documents from the period, Fern discusses the mythological figures Hengist and Horsa who appear in Bede's 8th-century Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, as well as the role that the former played in the epic poem Beowulf. Turning his attention to the human consumption of horse flesh in this period, he argues that it was only eaten rarely, usually as "a sacred activity".[23]

Sanmark's "Living On"

The penultimate paper in the anthology, "Living On: Ancestors and the Soul", is authored by Alexandra Sanmark, then a post doctoral Research Associate at the Millennium Institute Centre for Nordic Studies and Lecturer at the University of Western Australia's Department of History. In it, she takes a primarily historical approach to studying Anglo-Saxon conceptions of the soul, utilising comparisons from Norse paganism, which she recognises offers contemporary scholars "an echo or an analogy" of Anglo-Saxon paganism. Beginning by discussing the structure of Norse religious thinking, she describes the division between the "higher religion" devoted to the cult of the gods and the "lower religion" devoted to the veneration of animistic deities; Sanmark includes the Norse "cult of the ancestors" within this latter category. Expanding on this by exploring the Norse conception of the soul and the manner it which it might migrate in an animal form, she then turns her attention to similar evidence from Anglo-Saxon England, in particular discussing the ideas regarding an Anglo-Saxon shamanic tradition advocated by Stephen Glosecki.

At first dealing with the literary evidence from Anglo-Saxon poems like The Seafarer, she then turns her attention to the evidence from Anglo-Saxon art, again citing the theories of Glosecki. Looking at the link between an ancestor cult and places of burial – namely burial mounds, which she considers to be places of communication between the living and the dead – she makes use of Norse historical texts and ethnographic evidence from Eastern Europe to argue that the Anglo-Saxons probably used burial mounds for the same purposes. Moving on to look at the relation between the ancestors and the ritual consumption of alcoholic beverages, she primarily makes use of Norse sources, before discussing the role of the malevolent ancestors in the pre-Christian Anglo-Saxon worldview, highlighting the theories regarding deviant burials advocated by archaeologist Andrew Reynolds.[24]

Content and Williams' "Creating the Pagan English"

The final paper of the anthology, "Creating the Pagan English: From the Tudors to the Present Day", is the product of a collaboration between Howard Williams and Sue Content, a doctoral student at the University of Chester's Department of History and Archaeology. An overview of the history of Anglo-Saxon archaeological investigation into pre-Christian religion, it begins by looking at the manner in which the Anglo-Saxon pagans were glorified as proto-Protestants under the regime of the Tudor monarchs by the likes of Polydire Vergil and William Camden, before highlighting how Roman Catholic writers such as Richard Verstegen counteracted this by portraying these pagans as barbaric. Chronologically proceeding to the 18th century, he discusses the Nenia Britannica, a proto-archaeological work authored by the Reverend James Douglas which discussed the material evidence for early Anglo-Saxon belief. Moving into the Victorian era, Content and Williams note that the period between circa 1845 and 1860 was important for the antiquarian investigation of Anglo-Saxon paganism, in particular making reference to the work of John Young Akerman and John Mitchell Kemble. They argue that following the deaths of these two figures, there was a period of stagnation in Anglo-Saxon archaeology lasting until 1910, when interest in the subject once more emerged.[25]

Hutton's "Afterword: Caveats and Futures"

Ronald Hutton, in the book's afterword.[26]

The book's afterword, entitled "Caveats and Futures", was written by the English historian Ronald Hutton (1953–), then working at the University of Bristol. At the time a Commissioner for English Heritage, Hutton had previously written about Anglo-Saxon paganism in a chapter of his book The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy (1991).[27]

Hutton notes that the collection exposes Anglo-Saxon England as a "world of fluid religious identities" in which people "pick and mix between religious systems", developing "their own idiomatic and personal manifestations" of belief and practice.[26]

Reception and recognition

Academic and popular reviews

In a review published in the academic journal Anglo-Saxon England, Charlotte Behr of Roehampton University noted that Signals of Belief in Early England differed from many conference volumes in that the archaeologists who authored the book's papers appear to have undertaken "intense discussions" about how to carry out their research and interpret the evidence. Although she believed that there was much to commend in the anthology, she was wary that words like "superstitious", "magical", "numinous", "sacred", "sanctified" and "supernatural" had been used in a loose way as if they were synonyms despite the fact that they have distinct meanings. She was also critical of "two dozen spelling errors" and "minor factual mistakes" that made it into the text, but ultimately considered the presentation of the book to be "pleasing".[28]

Robert J. Wallis reviewed the book for Time and Mind: The Journal of Archaeology, Consciousness and Culture, noting that it would be enjoyed by those who liked the theoretical positions adopted in the 1990s, and that much of the language used is similar to that which has been employed in Bronze and Iron Age Studies. Expressing that its post-processualist angle has given Anglo-Saxon archaeology "a sharper edge", he opines that it constitutes essential reading for those interested in this area, but that a greater attention to anthropological theory, particularly regarding concepts of animism, shamanism, and totemism, needs to be developed.[29]

Writing in the Council for British Archaeology's bimestrial magazine, British Archaeology, the Early Medievalist Chris Scull praised Signals of Belief in Early England, opining that it should be "required reading" for any researcher investigating Anglo-Saxon beliefs. Arguing that the book was "[s]timulating and provocative", he believed that the most successful essays were those that engaged directly with the "material evidence and near-contemporary texts" rather than those which used later Scandinavian sources. Scull furthermore expressed his view that archaeologists should now discard the terms "pagan" and "paganism" when "considering the belief-worlds of early England."[30]

Legacy

In the year following the publication of Signals of Belief in Early England, the established Anglo-Saxonist Stephen Pollington published an overview of Anglo-Saxon paganism entitled The Elder Gods: The Otherworld of Early England.[31]

References

Footnotes

- Carver, Sanmark and Semple 2010. p. x.

- Carver, Sanmark and Semple 2010. p. v.

- Price 2010. p. xiv.

- Carver, Sanmark and Semple 2010. p. ix.

- Price 2010. p. xvi.

- Carver 2010. pp. 1–2.

- Carver 2010. pp. 3–4.

- Carver 2010. p. 4.

- Carver 2010. p. 5.

- Carver 2010. pp. 6–7.

- Carver 2010. p. 8.

- Carver 2010. pp. 8–11.

- Carver 2010. pp. 11–14.

- Carver 2010. pp. 14–15.

- Carver 2010. p. 16.

- Semple 2010. pp. 21–23.

- Semple 2010. pp. 24–48.

- Lund 2010. pp. 49–54.

- Lund 2010. pp. 54–66.

- Williams 2010. pp. 67–82.

- Walker 2010. pp. 83–102.

- Plusckowski 2010. pp. 103–127.

- Fern 2010. pp. 128–157.

- Sanmark 2010. pp. 158–180.

- Content and Williams 2010. pp. 181–200.

- Hutton 2010. p. 201.

- Hutton 1991.

- Behr 2011.

- Wallis 2012.

- Scull 2011.

- Pollington 2011.

Bibliography

- Academic books

- Carver, Martin; Sanmark, Alex; Semple, Sarah (eds.) (2010). Signals of Belief in Early England: Anglo-Saxon Paganism Revisited. Oxford and Oakville: Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-84217-395-4.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Hutton, Ronald (1991). The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy. Oxford, U.K. and Cambridge, U.S.A.: Blackwell.

- Pollington, Stephen (2011). The Elder Gods: The Otherworld of Early England. Little Downham, Cambs.: Anglo-Saxon Books. ISBN 978-1-898281-64-1.

- Academic papers

- Carver, Martin (2010). "Agency, Intellect and the Archaeological Agenda". Signals of Belief in Early England: Anglo-Saxon Paganism Revisited. Oxford and Oakville: Oxbow Books. pp. 1–20. ISBN 978-1-84217-395-4.

- Carver, Martin; Sanmark, Alex; Semple, Sarah (2010). "Preface". Signals of Belief in Early England: Anglo-Saxon Paganism Revisited. Oxford and Oakville: Oxbow Books. pp. ix–x. ISBN 978-1-84217-395-4.

- Hutton, Ronald (2010). "Afterword: Caveats and Futures". Signals of Belief in Early England: Anglo-Saxon Paganism Revisited. Oxford and Oakville: Oxbow Books. pp. 201–206. ISBN 978-1-84217-395-4.

- Lund, Julie (2010). "At the Water's Edge". Signals of Belief in Early England: Anglo-Saxon Paganism Revisited. Oxford and Oakville: Oxbow Books. pp. 49–66. ISBN 978-1-84217-395-4.

- Price, Neil (2010). "Foreword: Heathen Songs and Devil's Games". Signals of Belief in Early England: Anglo-Saxon Paganism Revisited. Oxford and Oakville: Oxbow Books. pp. xii–xvi. ISBN 978-1-84217-395-4.

- Sanmark, Alex (2010). "Living On: Ancestors and the Soul". Signals of Belief in Early England: Anglo-Saxon Paganism Revisited. Oxford and Oakville: Oxbow Books. pp. 158–180. ISBN 978-1-84217-395-4.

- Semple, Sarah (2010). "In the Open Air". Signals of Belief in Early England: Anglo-Saxon Paganism Revisited. Oxford and Oakville: Oxbow Books. pp. 21–48. ISBN 978-1-84217-395-4.

- Williams, Howard (2010). "At the Funeral". Signals of Belief in Early England: Anglo-Saxon Paganism Revisited. Oxford and Oakville: Oxbow Books. pp. 67–82. ISBN 978-1-84217-395-4.

- Reviews

- Behr, Charlotte (2011). "Review of Signals of Belief in Early England". Anglo-Saxon England. 21 (2). Cambridge University Press. pp. 316–317.

- Scull, Chris (May–June 2011). "Review of Signals of Belief in Early England". British Archaeology. 118. Council for British Archaeology. p. 55.

- Wallis, Robert J. (2012). "Review of Signals of Belief in Early England". Time and Mind: The Journal of Archaeology, Consciousness and Culture. 5 (2). pp. 229–232.