Signal (software)

Signal is a cross-platform encrypted messaging service developed by the Signal Foundation and Signal Messenger LLC. It uses the Internet to send one-to-one and group messages, which can include files, voice notes, images and videos.[16] Its mobile apps can also make one-to-one voice and video calls,[17] and the Android version can optionally function as an SMS app.[18]

| |||||||

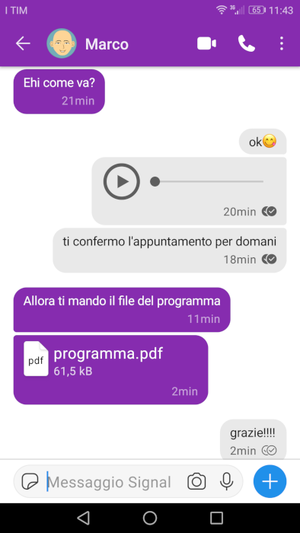

Screenshot  Screenshot of Signal Android version 4.52 (December 2019) | |||||||

| Developer(s) |

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial release | July 29, 2014[1][2] | ||||||

| Stable release |

| ||||||

| Preview release |

| ||||||

| Repository | | ||||||

| Operating system | |||||||

| Type | Encrypted voice calling, video calling and instant messaging | ||||||

| License | |||||||

| Website | signal | ||||||

Signal uses standard cellular telephone numbers as identifiers and secures all communications to other Signal users with end-to-end encryption. The apps include mechanisms by which users can independently verify the identity of their contacts and the integrity of the data channel.[18][19]

All Signal software is free and open-source. Its clients are published under the GPLv3 license,[12][13][14] while the server code is published under the AGPLv3 license.[15] The non-profit Signal Foundation was launched in February 2018 with initial funding of $50 million.[20]

History

2010–2013: Origins

Signal is the successor of the RedPhone encrypted voice calling app and the TextSecure encrypted texting program. The beta versions of RedPhone and TextSecure were first launched in May 2010 by Whisper Systems,[21] a startup company co-founded by security researcher Moxie Marlinspike and roboticist Stuart Anderson.[39][40] Whisper Systems also produced a firewall and tools for encrypting other forms of data.[39][41] All of these were proprietary enterprise mobile security software and were only available for Android.

In November 2011, Whisper Systems announced that it had been acquired by Twitter. The financial terms of the deal were not disclosed by either company.[22] The acquisition was done "primarily so that Mr. Marlinspike could help the then-startup improve its security".[23] Shortly after the acquisition, Whisper Systems' RedPhone service was made unavailable.[42] Some criticized the removal, arguing that the software was "specifically targeted [to help] people under repressive regimes" and that it left people like the Egyptians in "a dangerous position" during the events of the Egyptian revolution of 2011.[43]

Twitter released TextSecure as free and open-source software under the GPLv3 license in December 2011.[39][44][24][45] RedPhone was also released under the same license in July 2012.[25] Marlinspike later left Twitter and founded Open Whisper Systems as a collaborative Open Source project for the continued development of TextSecure and RedPhone.[1][27]

2013–2018: Open Whisper Systems

Open Whisper Systems' website was launched in January 2013.[27]

In February 2014, Open Whisper Systems introduced the second version of their TextSecure Protocol (now Signal Protocol), which added end-to-end encrypted group chat and instant messaging capabilities to TextSecure.[28] Toward the end of July 2014, they announced plans to unify the RedPhone and TextSecure applications as Signal.[46] This announcement coincided with the initial release of Signal as a RedPhone counterpart for iOS. The developers said that their next steps would be to provide TextSecure instant messaging capabilities for iOS, unify the RedPhone and TextSecure applications on Android, and launch a web client.[46] Signal was the first iOS app to enable easy, strongly encrypted voice calls for free.[1][29] TextSecure compatibility was added to the iOS application in March 2015.[47][31]

From its launch in May 2010[21] until March 2015, the Android version of Signal (then called TextSecure) included support for encrypted SMS/MMS messaging.[48] From version 2.7.0 onward, the Android application only supported sending and receiving encrypted messages via the data channel.[49] Reasons for this included security flaws of SMS/MMS and problems with the key exchange.[49] Open Whisper Systems' abandonment of SMS/MMS encryption prompted some users to create a fork named Silence (initially called SMSSecure[50]) that is meant solely for the exchange of encrypted SMS and MMS messages.[51][52]

In November 2015, the TextSecure and RedPhone applications on Android were merged to become Signal for Android.[32] A month later, Open Whisper Systems announced Signal Desktop, a Chrome app that could link with a Signal mobile client.[33] At launch, the app could only be linked with the Android version of Signal.[53] On September 26, 2016, Open Whisper Systems announced that Signal Desktop could now be linked with the iOS version of Signal as well.[54] On October 31, 2017, Open Whisper Systems announced that the Chrome app was deprecated.[10] At the same time, they announced the release of a standalone desktop client (based on the Electron framework[14]) for Windows, MacOS and certain Linux distributions.[10][55]

On October 4, 2016, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and Open Whisper Systems published a series of documents revealing that OWS had received a subpoena requiring them to provide information associated with two phone numbers for a federal grand jury investigation in the first half of 2016.[56][57][58] Only one of the two phone numbers was registered on Signal, and because of how the service is designed, OWS was only able to provide "the time the user's account had been created and the last time it had connected to the service".[57][56] Along with the subpoena, OWS received a gag order requiring OWS not to tell anyone about the subpoena for one year.[56] OWS approached the ACLU, and they were able to lift part of the gag order after challenging it in court.[56] OWS said it was the first time they had received a subpoena, and that they were committed to treat "any future requests the same way".[58]

In March 2017, Open Whisper Systems transitioned Signal's calling system from RedPhone to WebRTC, also adding the ability to make video calls.[35][59][17]

2018–present: Signal Messenger

On February 21, 2018, Moxie Marlinspike and WhatsApp co-founder Brian Acton announced the formation of the Signal Foundation, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization whose mission is "to support, accelerate, and broaden Signal’s mission of making private communication accessible and ubiquitous."[36][20] The foundation was started with an initial $50 million in funding from Acton, who had left WhatsApp's parent company Facebook in September 2017.[20] According to the announcement, Acton is the foundation's Executive Chairman and Marlinspike continues as the CEO of Signal Messenger.[36]

Between November 2019 and February 2020, Signal added support for iPads, view-once images and videos, stickers, and reactions.[38] They also announced plans for a new group messaging system and an "experimental method for storing encrypted contacts in the cloud."[38]

Signal's popularity in the United States has reportedly increased substantially due to the George Floyd protests, particularly among organizers and activists.[60] In June 2020, Signal Foundation co-founder Moxie Marlinspike announced the release of a feature that enables users to blur faces in photos. This new feature was launched after U.S. authorities increased their efforts to monitor the protests.[61]

Features

Signal allows users to make voice and video[17] calls to other Signal users on iOS and Android. All calls are made over a Wi-Fi or data connection and (with the exception of data fees) are free of charge, including long distance and international.[29] Signal also allows users to send text messages, files,[16] voice notes, pictures, GIFs,[62] and video messages over a Wi-Fi or data connection to other Signal users on iOS, Android and a desktop app. The app also supports group messaging.

All communications to other Signal users are automatically end-to-end encrypted. The keys that are used to encrypt the user's communications are generated and stored at the endpoints (i.e. by users, not by servers).[63] To verify that a correspondent is really the person that they claim to be, Signal users can compare key fingerprints (or scan QR codes) out-of-band.[64] The app employs a trust-on-first-use mechanism in order to notify the user if a correspondent's key changes.[64]

On Android, users can opt into making Signal the default SMS/MMS application, allowing them to send and receive unencrypted SMS messages in addition to the standard end-to-end encrypted Signal messages.[28] Users can then use the same application to communicate with contacts who do not have Signal.[28] Sending a message unencrypted is also available as an override between Signal users.[65]

TextSecure allowed the user to set a passphrase that encrypted the local message database and the user's encryption keys.[66] This did not encrypt the user's contact database or message timestamps.[66] The Signal applications on Android and iOS can be locked with the phone's pin, passphrase, or biometric authentication.[67] The user can define a "screen lock timeout" interval, providing an additional protection mechanism in case the phone is lost or stolen.[64][67]

Signal also allows users to set timers to messages.[68] After a specified time interval, the messages will be deleted from both the sender's and the receivers' devices.[68] The time interval can be between five seconds and one week long,[68] and the timer begins for each recipient once they have read their copy of the message.[69] The developers have stressed that this is meant to be "a collaborative feature for conversations where all participants want to automate minimalist data hygiene, not for situations where your contact is your adversary".[68][69]

Signal excludes users' messages from non-encrypted cloud backups by default.[70]

Signal has support for read receipts and typing indicators, both of which can be disabled.[71][72]

Signal allows users to automatically blur faces of people in photos to protect their identities.[73][74][75][76]

Limitations

Signal requires that the user provides a phone number for verification,[77] eliminating the need for user names or passwords and facilitating contact discovery (see below).[78] The number does not have to be the same as on the device's SIM card; it can also be a VoIP number[77] or a landline as long as the user can receive the verification code and have a separate device to set up the software. A number can only be registered on one mobile device at a time.[79]

This mandatory connection to a phone number (a feature Signal shares with WhatsApp, KakaoTalk, and others) has been criticized as a "major issue" for privacy-conscious users who are not comfortable with giving out their private phone number.[78] A workaround is to use a secondary phone number.[78] The option to choose a public, changeable username instead of sharing one's phone number with everyone they message (or share a group with) is a widely requested feature, which as of June 2020 has not yet been implemented.[78][80][81] Signal in 2019 announced plans to implement this feature, overcoming the challenges associated with storing users' social graphs by using what they called Secure Value Recovery (SVR).[82] This allows users to client-side encrypt their Signal contacts with an alphanumeric passphrase (which Signal calls a PIN[83]) and uses Intel SGX to limit the number of passphrase guesses, alleviating the risk of server-side brute-force attempts.[82][84][85] Cryptography expert Matthew D. Green described this method as "sophisticated work,"[86] but also expressed concerns that the data the system was protecting should not rely on the security of SGX, which has been repeatedly broken.[87][88]

Using phone numbers as identifiers may also create security risks that arise from the possibility of an attacker taking over a phone number.[78] This can be mitigated by enabling an optional Registration Lock PIN in Signal's privacy settings.[89]

Android-specific

From February 2014[28] to February 2017,[90] Signal's official Android client required the proprietary Google Play Services because the app was dependent on Google's GCM push-messaging framework.[91][90] In March 2015, Signal moved to a model of handling the app's message delivery themselves and only using GCM for a wakeup event.[92] In February 2017, Signal's developers implemented WebSocket support into the client, making it possible for it to be used without Google Play Services.[90]

Desktop-specific

Setting up Signal's desktop app requires that the user first install Signal on an Android or iOS based smartphone with an Internet connection.[11] Once the desktop app has been linked to the user's account, it will function as an independent client; the mobile app does not need to be present or online.[93] Users can link up to 5 desktop apps to their account.[79]

As of March 2019, Signal's desktop app does not include support for voice or video calling.[94]

The Signal desktop app does not work well in an IPv6 only environment, even when NAT64/DNS64 is present. Despite an announcement in 2016 that GIF support would be added "soon", the desktop app does not allow sending animated GIFs.

Usability

In July 2016, the Internet Society published a user study that assessed the ability of Signal users to detect and deter man-in-the-middle attacks.[19] The study concluded that 21 out of 28 participants failed to correctly compare public key fingerprints in order to verify the identity of other Signal users, and that the majority of these users still believed they had succeeded, while in reality they failed.[19] Four months later, Signal's user interface was updated to make verifying the identity of other Signal users simpler.[95]

Before version 4.17,[96] the Signal Android client could only make plain text-only backups of the message history, i.e. without media messages.[97][98] On February 26, 2018, Signal added support for "full backup/restore to SD card",[99] and as of version 4.17, users are able to restore their entire message history when switching to a new Android phone.[96] The Signal iOS client does not support exporting or importing the user's messaging history.[100]

Architecture

Encryption protocols

Signal messages are encrypted with the Signal Protocol (formerly known as the TextSecure Protocol). The protocol combines the Double Ratchet Algorithm, prekeys, and a Triple Diffie-Hellman (3XDH) handshake.[101] It uses Curve25519, AES-256, and HMAC-SHA256 as primitives.[18] The protocol provides confidentiality, integrity, authentication, participant consistency, destination validation, forward secrecy, backward secrecy (aka future secrecy), causality preservation, message unlinkability, message repudiation, participation repudiation, and asynchronicity.[102] It does not provide anonymity preservation, and requires servers for the relaying of messages and storing of public key material.[102]

The Signal Protocol also supports end-to-end encrypted group chats. The group chat protocol is a combination of a pairwise double ratchet and multicast encryption.[102] In addition to the properties provided by the one-to-one protocol, the group chat protocol provides speaker consistency, out-of-order resilience, dropped message resilience, computational equality, trust equality, subgroup messaging, as well as contractible and expandable membership.[102]

In October 2014, researchers from Ruhr University Bochum published an analysis of the Signal Protocol.[18] Among other findings, they presented an unknown key-share attack on the protocol, but in general, they found that it was secure.[103] In October 2016, researchers from UK's University of Oxford, Queensland University of Technology in Australia, and Canada's McMaster University published a formal analysis of the protocol.[104][105] They concluded that the protocol was cryptographically sound.[104][105] In July 2017, researchers from Ruhr University Bochum found during another analysis of group messengers a purely theoretic attack against the group protocol of Signal: A user who knows the secret group ID of a group (due to having been a group member previously or stealing it from a member's device) can become a member of the group. Since the group ID cannot be guessed and such member changes are displayed to the remaining members, this attack is likely to be difficult to carry out without being detected.[106]

As of August 2018, the Signal Protocol has been implemented into WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, Skype,[107] and Google Allo,[108] making it possible for the conversations of "more than a billion people worldwide" to be end-to-end encrypted.[109] In Google Allo, Skype and Facebook Messenger, conversations are not encrypted with the Signal Protocol by default; they only offer end-to-end encryption in an optional mode.[70][110][107][111]

Up until March 2017, Signal's voice calls were encrypted with SRTP and the ZRTP key-agreement protocol, which was developed by Phil Zimmermann.[1][112] As of March 2017, Signal's voice and video calling functionalities use the app's Signal Protocol channel for authentication instead of ZRTP.[113][35][17]

Authentication

To verify that a correspondent is really the person that they claim to be, Signal users can compare key fingerprints (or scan QR codes) out-of-band.[64] The app employs a trust on first use mechanism in order to notify the user if a correspondent's key changes.[64]

Servers

Signal relies on centralized servers that are maintained by Signal Messenger. In addition to routing Signal's messages, the servers also facilitate the discovery of contacts who are also registered Signal users and the automatic exchange of users' public keys. By default, Signal's voice and video calls are peer-to-peer.[17] If the caller is not in the receiver's address book, the call is routed through a server in order to hide the users' IP addresses.[17]

Contact discovery

The servers store registered users' phone numbers, public key material and push tokens which are necessary for setting up calls and transmitting messages.[114] In order to determine which contacts are also Signal users, cryptographic hashes of the user's contact numbers are periodically transmitted to the server.[115] The server then checks to see if those match any of the SHA256 hashes of registered users and tells the client if any matches are found.[115] The hashed numbers are thereafter discarded from the server.[114] In 2014, Moxie Marlinspike wrote that it is easy to calculate a map of all possible hash inputs to hash outputs and reverse the mapping because of the limited preimage space (the set of all possible hash inputs) of phone numbers, and that a "practical privacy preserving contact discovery remains an unsolved problem."[116][115] In September 2017, Signal's developers announced that they were working on a way for the Signal client applications to "efficiently and scalably determine whether the contacts in their address book are Signal users without revealing the contacts in their address book to the Signal service."[117][118]

Metadata

All client-server communications are protected by TLS.[112][119] In October 2018, Signal deployed a "Sealed Sender" feature which encrypts the sender's information using the sender and recipient identity keys, and includes it inside the message. With this feature Signal's servers can no longer see who is sending messages to whom.[120] Signal's privacy policy states that any identifiers are only kept on the servers as long as necessary in order to place each call or transmit each message.[114] Signal's developers have asserted that their servers do not keep logs about who called whom and when.[121] In June 2016, Marlinspike told The Intercept that "the closest piece of information to metadata that the Signal server stores is the last time each user connected to the server, and the precision of this information is reduced to the day, rather than the hour, minute, and second".[70]

The group messaging mechanism is designed so that the servers do not have access to the membership list, group title, or group icon.[49] Instead, the creation, updating, joining, and leaving of groups is done by the clients, which deliver pairwise messages to the participants in the same way that one-to-one messages are delivered.[122][123]

Federation

Signal's server architecture was federated between December 2013 and February 2016. In December 2013, it was announced that the messaging protocol that is used in Signal had successfully been integrated into the Android-based open-source operating system CyanogenMod.[124][125][126] Since CyanogenMod 11.0, the client logic was contained in a system app called WhisperPush. According to Signal's developers, the Cyanogen team ran their own Signal messaging server for WhisperPush clients, which federated with the main server, so that both clients could exchange messages with each other.[126] The WhisperPush source code was available under the GPLv3 license.[127] In February 2016, the CyanogenMod team discontinued WhisperPush and recommended that its users switch to Signal.[128] In May 2016, Moxie Marlinspike wrote that federation with the CyanogenMod servers had degraded the user experience and held back development, and that their servers will probably not federate with other servers again.[129]

In May 2016, Moxie Marlinspike requested that a third-party client called LibreSignal not use the Signal service or the Signal name.[129] As a result, on 24 May 2016 the LibreSignal project posted that the project was "abandoned".[130] The functionality provided by LibreSignal was subsequently incorporated into Signal by Marlinspike.[131]

Licensing

The complete source code of the Signal clients for Android, iOS and desktop is available on GitHub under a free software license.[12][13][14] This enables interested parties to examine the code and help the developers verify that everything is behaving as expected. It also allows advanced users to compile their own copies of the applications and compare them with the versions that are distributed by Signal Messenger. In March 2016, Moxie Marlinspike wrote that, apart from some shared libraries that are not compiled with the project build due to a lack of Gradle NDK support, Signal for Android is reproducible.[132] Signal's servers are also open source.[15]

Distribution

Signal is officially distributed through the Google Play store, Apple's App Store, and the official website. Applications distributed via Google Play are signed by the developer of the application, and the Android operating system checks that updates are signed with the same key, preventing others from distributing updates that the developer themselves did not sign.[133][134] The same applies to iOS applications that are distributed via Apple's App Store.[135] As of March 2017, the Android version of Signal can also be downloaded as a separate APK package binary from Signal Messenger's website.[136]

Reception

In October 2014, the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) included Signal in their updated surveillance self-defense guide.[137] In November 2014, Signal received a perfect score on the EFF's secure messaging scorecard;[63] it received points for having communications encrypted in transit, having communications encrypted with keys the provider doesn't have access to (end-to-end encryption), making it possible for users to independently verify their correspondents' identities, having past communications secure if the keys are stolen (forward secrecy), having the code open to independent review (open source), having the security designs well-documented, and having a recent independent security audit.[63] At the time, "ChatSecure + Orbot", Pidgin (with OTR), Silent Phone, and Telegram's optional "secret chats" also received seven out of seven points on the scorecard.[63]

On December 28, 2014, Der Spiegel published slides from an internal NSA presentation dating to June 2012 in which the NSA deemed Signal's encrypted voice calling component (RedPhone) on its own as a "major threat" to its mission, and when used in conjunction with other privacy tools such as Cspace, Tor, Tails, and TrueCrypt was ranked as "catastrophic", leading to a "near-total loss/lack of insight to target communications, presence..."[138][139]

Former NSA contractor Edward Snowden has endorsed Signal on multiple occasions.[33] In his keynote speech at SXSW in March 2014, he praised Signal's predecessors (TextSecure and RedPhone) for their ease of use.[140] During an interview with The New Yorker in October 2014, he recommended using "anything from Moxie Marlinspike and Open Whisper Systems".[141] During a remote appearance at an event hosted by Ryerson University and Canadian Journalists for Free Expression in March 2015, Snowden said that Signal is "very good" and that he knew the security model.[142] Asked about encrypted messaging apps during a Reddit AMA in May 2015, he recommended Signal.[143][144] In November 2015, Snowden tweeted that he used Signal "every day".[32][145]

In September 2015, the American Civil Liberties Union called on officials at the U.S. Capitol to ensure that lawmakers and staff members have secure communications technology.[146] One of the applications that the ACLU recommended in their letter to the Senate Sergeant at Arms and to the House Sergeant at Arms was Signal, writing:

One of the most widely respected encrypted communication apps, Signal, from Open Whisper Systems, has received significant financial support from the U.S. government, has been audited by independent security experts, and is now widely used by computer security professionals, many of the top national security journalists, and public interest advocates. Indeed, members of the ACLU’s own legal department regularly use Signal to make encrypted telephone calls.[147]

In March 2017, Signal was approved by the Sergeant at Arms of the U.S. Senate for use by senators and their staff.[148][149]

Following the 2016 Democratic National Committee email leak, Vanity Fair reported that Marc Elias, the general counsel for Hillary Clinton's presidential campaign, had instructed DNC staffers to exclusively use Signal when saying anything "remotely contentious or disparaging" about Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump.[150][151]

In February 2020, the European Commission has recommended that its staff use Signal.[152] Concurrently with the George Floyd protests, Signal was downloaded 121,000 times in the United States between 25 May and 4 June in 2020.[153] Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey advised the public to download Signal as protests spread in the US.[154]

In July 2020, Signal became the most downloaded app in Hong Kong on both Apple's App Store and Google's Play Store after the passage of the Hong Kong National Security Law.[155]

As of 2020, Signal is one of the contact methods to securely provide tips to major news outlets such as Washington Post,[156] The Guardian,[157] New York Times[158] and Wall Street Journal.[159]

Blocking

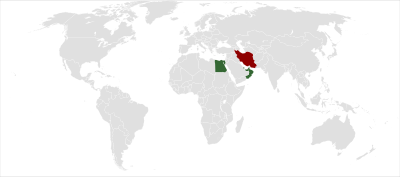

In December 2016, Egypt blocked access to Signal.[160] In response, Signal's developers added domain fronting to their service.[161] This allows Signal users in a specific country to circumvent censorship by making it look like they are connecting to a different internet-based service.[161][162] As of October 2017, Signal's domain fronting is enabled by default in Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, Oman and Qatar.[163]

As of January 2018, Signal is blocked in Iran.[164][165] Signal's domain fronting feature relies on the Google App Engine service.[165][164] This does not work in Iran because Google has blocked Iranian access to GAE in order to comply with U.S. sanctions.[164][166]

In early 2018, Google App Engine made an internal change to stop domain fronting for all countries. Due to this issue, Signal made a public change to use Amazon CloudFront for domain fronting. However, AWS also announced that they would be making changes to their service to prevent domain fronting. As a result, Signal said that they would start investigating new methods/approaches.[167][168] Signal switched from AWS back to Google in April 2019.[169]

Developers and funding

The development of Signal and its predecessors at Open Whisper Systems was funded by a combination of consulting contracts, donations and grants.[170] The Freedom of the Press Foundation acted as Signal's fiscal sponsor.[36][171][172] Between 2013 and 2016, the project received grants from the Knight Foundation,[173] the Shuttleworth Foundation,[174] and almost $3M from the US-Government sponsored Open Technology Fund.[175] Signal is now developed by Signal Messenger LLC, a software company founded by Moxie Marlinspike and Brian Acton in 2018, which is wholly owned by a tax-exempt nonprofit corporation called the Signal Technology Foundation, also created by them in 2018. The Foundation was funded with an initial loan of $50 million from Acton, "to support, accelerate, and broaden Signal’s mission of making private communication accessible and ubiquitous."[36][20][176] All of the organization's products are published as free and open-source software.

See also

- Comparison of instant messaging clients

- Comparison of VoIP software

- Internet privacy

- List of video telecommunication services and product brands

- Secure communication

References

- Greenberg, Andy (29 July 2014). "Your iPhone Can Finally Make Free, Encrypted Calls". Wired. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- Marlinspike, Moxie (29 July 2014). "Free, Worldwide, Encrypted Phone Calls for iPhone". Open Whisper Systems. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- Signal Foundation. "Signal Private Messenger - Apps on Google Play". play.google.com.

- Signal Messenger, LLC. "Signal - Private Messenger on the App Store". apps.apple.com.

- Open Whisper Systems, "Releases - signalapp/Signal-Desktop", github.com

- "Signal Private Messenger APKs". APKMirror.

- "Releases · signalapp/Signal-Android". github.com.

- "Releases · signalapp/Signal-iOS". github.com.

- "Releases · signalapp/Signal-Desktop". github.com.

- Nonnenberg, Scott (31 October 2017). "Standalone Signal Desktop". Open Whisper Systems. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- "Installing Signal - Signal Support".

- Open Whisper Systems. "Signal-iOS". GitHub. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- Open Whisper Systems. "Signal-Android". GitHub. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- Open Whisper Systems. "Signal-Desktop". GitHub. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- Open Whisper Systems. "Signal-Server". GitHub. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- Signal [@signalapp] (1 May 2017). "Today's Signal release for Android, iOS, and Desktop includes the ability to send arbitrary file types" (Tweet). Retrieved 5 November 2018 – via Twitter.

- Mott, Nathaniel (14 March 2017). "Signal's Encrypted Video Calling For iOS, Android Leaves Beta". Tom's Hardware. Purch Group, Inc. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- Frosch et al. 2016

- Schröder et al. 2016

- Greenberg, Andy (21 February 2018). "WhatsApp Co-Founder Puts $50M Into Signal To Supercharge Encrypted Messaging". Wired. Condé Nast. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- "Announcing the public beta". Whisper Systems. 25 May 2010. Archived from the original on 30 May 2010. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- Cheredar, Tom (28 November 2011). "Twitter acquires Android security startup Whisper Systems". VentureBeat. Retrieved 2011-12-21.

- Yadron, Danny (9 July 2015). "Moxie Marlinspike: The Coder Who Encrypted Your Texts". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- "TextSecure is now Open Source!". Whisper Systems. 20 December 2011. Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- "RedPhone is now Open Source!". Whisper Systems. 18 July 2012. Archived from the original on 31 July 2012. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- Yadron, Danny (10 July 2015). "What Moxie Marlinspike Did at Twitter". Digits. The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 18 March 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- "A New Home". Open Whisper Systems. 2013-01-21. Retrieved 2014-03-01.

- Donohue, Brian (24 February 2014). "TextSecure Sheds SMS in Latest Version". Threatpost. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- Evans, Jon (29 July 2014). "Talk Private To Me: Free, Worldwide, Encrypted Voice Calls With Signal For iPhone". TechCrunch. AOL.

- Open Whisper Systems (6 March 2015). "Saying goodbye to encrypted SMS/MMS". Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- Geuss, Megan (2015-03-03). "Now you can easily send (free!) encrypted messages between Android, iOS". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2015-03-03.

- Greenberg, Andy (2 November 2015). "Signal, the Snowden-Approved Crypto App, Comes to Android". Wired. Condé Nast. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- Franceschi-Bicchierai, Lorenzo (2 December 2015). "Snowden's Favorite Chat App Is Coming to Your Computer". Motherboard. Vice Media LLC. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- Coldewey, Devin (31 October 2017). "Signal escapes the confines of the browser with a standalone desktop app". TechCrunch. Oath Tech Network. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- Marlinspike, Moxie (14 February 2017). "Video calls for Signal now in public beta". Open Whisper Systems. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- Marlinspike, Moxie; Acton, Brian (21 February 2018). "Signal Foundation". Signal.org. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- Lund, Joshua (27 November 2019). "Signal for iPad, and other iOS improvements". Signal.org. Signal Messenger. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- Greenberg, Andy (14 February 2020). "Signal Is Finally Bringing Its Secure Messaging to the Masses". Wired. Condé Nast. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- Garling, Caleb (20 December 2011). "Twitter Open Sources Its Android Moxie | Wired Enterprise". Wired. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- "Company Overview of Whisper Systems Inc". Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved 2014-03-04.

- Greenberg, Andy (2010-05-25). "Android App Aims to Allow Wiretap-Proof Cell Phone Calls". Forbes. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- Greenberg, Andy (2011-11-28). "Twitter Acquires Moxie Marlinspike's Encryption Startup Whisper Systems". Forbes. Retrieved 2011-12-21.

- Garling, Caleb (28 November 2011). "Twitter Buys Some Middle East Moxie | Wired Enterprise". Wired. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- Aniszczyk, Chris (20 December 2011). "The Whispers Are True". The Twitter Developer Blog. Twitter. Archived from the original on 24 October 2014. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- Pachal, Pete (2011-12-20). "Twitter Takes TextSecure, Texting App for Dissidents, Open Source". Mashable. Retrieved 2014-03-01.

- Mimoso, Michael (29 July 2014). "New Signal App Brings Encrypted Calling to iPhone". Threatpost.

- Lee, Micah (2015-03-02). "You Should Really Consider Installing Signal, an Encrypted Messaging App for iPhone". The Intercept. Retrieved 2015-03-03.

- Open Whisper Systems (6 March 2015). "Saying goodbye to encrypted SMS/MMS". Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- Rottermanner et al. 2015, p. 3

- BastienLQ (20 April 2016). "Change the name of SMSSecure". GitHub (pull request). SilenceIM. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- "TextSecure-Fork bringt SMS-Verschlüsselung zurück". Heise (in German). 2 April 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- "SMSSecure: TextSecure-Abspaltung belebt SMS-Verschlüsselung wieder". Der Standard (in German). 3 April 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- Coldewey, Devin (7 April 2016). "Now's your chance to try Signal's desktop Chrome app". TechCrunch. AOL Inc. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- Marlinspike, Moxie (26 September 2016). "Desktop support comes to Signal for iPhone". Open Whisper Systems. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- Coldewey, Devin (31 October 2017). "Signal escapes the confines of the browser with a standalone desktop app". TechCrunch. Oath Tech Network. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- Perlroth, Nicole; Benner, Katie (4 October 2016). "Subpoenas and Gag Orders Show Government Overreach, Tech Companies Argue". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- Kaufman, Brett Max (4 October 2016). "New Documents Reveal Government Effort to Impose Secrecy on Encryption Company" (Blog post). American Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- "Grand jury subpoena for Signal user data, Eastern District of Virginia". Open Whisper Systems. 4 October 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- Marlinspike, Moxie (13 March 2017). "Video calls for Signal out of beta". Open Whisper Systems. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- Nierenberg, Amelia (2020-06-12). "Signal Downloads Are Way Up Since the Protests Began". The New York Times.

- Lyngaas, Sean (2020-06-04). "Signal aims to boost protesters' phone security at George Floyd demonstrations with face-blurring tool". CyberScoop. Retrieved 2020-06-14.

- Lund, Joshua (1 November 2017). "Expanding Signal GIF search". Open Whisper Systems. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- "Secure Messaging Scorecard. Which apps and tools actually keep your messages safe?". Electronic Frontier Foundation. 4 November 2014.

- Rottermanner et al. 2015, p. 5

- https://support.signal.org/hc/en-us/articles/212535548-How-do-I-send-an-insecure-SMS-

- Rottermanner et al. 2015, p. 9

- "Screen Lock". support.signal.org. Signal. n.d. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- Greenberg, Andy (11 October 2016). "Signal, the Cypherpunk App of Choice, Adds Disappearing Messages". Wired. Condé Nast. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- Marlinspike, Moxie (11 October 2016). "Disappearing messages for Signal". Open Whisper Systems. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- Lee, Micah (22 June 2016). "Battle of the Secure Messaging Apps: How Signal Beats WhatsApp". The Intercept. First Look Media. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- "How do I know if my message was delivered or read?". Signal Support Center. Signal Messenger. Retrieved 2019-02-22.

- "Typing Indicators". Signal Support Center. Signal Messenger. Retrieved 2019-02-22.

- O'Flaherty, Kate. "Signal Will Now Blur Protesters' Faces: Here's How It Works". Forbes. Retrieved 2020-06-05.

- Vincent, James (2020-06-04). "Signal announces new face-blurring tool for Android and iOS". The Verge. Retrieved 2020-06-05.

- Yeo, Amanda. "Signal's new blur tool will help hide protesters' identities". Mashable. Retrieved 2020-06-05.

- "Blur tools for Signal". signal.org. Retrieved 2020-06-05.

- Kolenkina, Masha (20 November 2015). "Will any phone number work? How do I get a verification number?". Open Whisper Systems. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- Lee, Micah (2017-09-28). "How to Use Signal Without Giving Out Your Phone Number". The Intercept. Retrieved 2018-02-25.

- "Troubleshooting multiple devices". support.signal.org. Signal Messenger LLC. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- "Allow different kinds of identifiers for registration · Issue #1085 · signalapp/Signal-Android". GitHub. Retrieved 2018-02-25.

- "Discussion: A proposal for alternative primary identifiers". Signal Community. 24 May 2018. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- "Signal Blog: Secure Value Recovery". signal.org.

- "Signal Blog: Introducing Signal PINs". signal.org.

- "Discussion: Technology Preview for secure value recovery". Signal Community. 19 December 2019.

- "Tweet by Signal". Twitter. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- "Tweet by Matthew Green". Twitter. 19 December 2019. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- "Second Tweet by Matthew Green". Twitter. 19 December 2019. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- "Third Tweet by Matthew Green". Twitter. 9 June 2020. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- "Registration Lock". support.signal.org. Signal Messenger LLC. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- Marlinspike, Moxie (20 February 2017). "Support for using Signal without Play Services". GitHub. Open Whisper Systems. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- Kolenkina, Masha (25 February 2016). "Why do I need Google Play installed to use Signal? How can I get Signal APK?". Open Whisper Systems. Archived from the original on 2 April 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- Marlinspike, Moxie (6 March 2015). "Saying goodbye to encrypted SMS/MMS". Open Whisper Systems. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- "Can I send SMS/MMS with Signal?". support.signal.org. Signal Messenger LLC. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- "Adding voice and video call support to the desktop app". Signal Community (Forum). 2017-06-04. Retrieved 2019-03-19.

- Marlinspike, Moxie (17 November 2016). "Safety number updates". Open Whisper Systems. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- Kolenkina, Masha. "Restoring messages on Signal Android". Signal.org. Open Whisper Systems. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- "Encrypted backup". Signal Community (Internet forum). 2017-08-16. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- "Media Not Exporting to XML #1619". GitHub. 17 July 2014. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- Marlinspike, Moxie (26 February 2018). "Support for full backup/restore to sdcard". GitHub. Open Whisper Systems. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- "iOS Import/Export #2542". GitHub. 16 September 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- Unger et al. 2015, p. 241

- Unger et al. 2015, p. 239

- Pauli, Darren. "Auditors find encrypted chat client TextSecure is secure". The Register. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- Brook, Chris (10 November 2016). "Signal Audit Reveals Protocol Cryptographically Sound". Threatpost. Kaspersky Lab. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- Cohn-Gordon et al. 2016

- Rösler, Paul; Mainka, Christian; Schwenk, Jörg (2017). "More is Less: On the End-to-End Security of Group Chats in Signal, WhatsApp, and Threema" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Lund, Joshua (11 January 2018). "Signal partners with Microsoft to bring end-to-end encryption to Skype". Open Whisper Systems. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- Marlinspike, Moxie (18 May 2016). "Open Whisper Systems partners with Google on end-to-end encryption for Allo". Open Whisper Systems. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- "Moxie Marlinspike - 40 under 40". Fortune. Time Inc. 2016. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- Marlinspike, Moxie (8 July 2016). "Facebook Messenger deploys Signal Protocol for end to end encryption". Open Whisper Systems. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- Gebhart, Gennie (3 October 2016). "Google's Allo Sends The Wrong Message About Encryption". Electronic Frontier Foundation. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- Marlinspike, Moxie (17 July 2012). "Encryption Protocols". GitHub. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- Greenberg, Andy (14 February 2017). "The Best Encrypted Chat App Now Does Video Calls Too". Wired. Condé Nast. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- "Privacy Policy". Signal Messenger LLC. 25 May 2018. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- Moxie Marlinspike (3 January 2013). "The Difficulty Of Private Contact Discovery". Open Whisper Systems. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- Rottermanner et al. 2015, p. 4

- Marlinspike, Moxie (26 September 2017). "Technology preview: Private contact discovery for Signal". Open Whisper Systems. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- Greenberg, Andy (26 September 2017). "Signal Has a Fix for Apps' Contact-Leaking Problem". Wired. Condé Nast. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- Frosch et al. 2016, p. 7

- "Signal >> Blog >> Technology preview: Sealed sender for Signal". Signal.org. October 29, 2018.

- Brandom, Russell (29 July 2014). "Signal brings painless encrypted calling to iOS". The Verge. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- Moxie Marlinspike (5 May 2014). "Private Group Messaging". Open Whisper Systems. Retrieved 2014-07-09.

- Moxie Marlinspike (24 February 2014). "The New TextSecure: Privacy Beyond SMS". Open Whisper Systems. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- Andy Greenberg (2013-12-09). "Ten Million More Android Users' Text Messages Will Soon Be Encrypted By Default". Forbes. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- Seth Schoen (2013-12-28). "2013 in Review: Encrypting the Web Takes A Huge Leap Forward". Electronic Frontier Foundation. Retrieved 2014-03-01.

- Moxie Marlinspike (2013-12-09). "TextSecure, Now With 10 Million More Users". Open Whisper Systems. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- CyanogenMod (Jan 7, 2014). "android_external_whispersystems_WhisperPush". GitHub. Retrieved Mar 26, 2015.

- Sinha, Robin (20 January 2016). "CyanogenMod to Shutter WhisperPush Messaging Service on February 1". Gadgets360. NDTV. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- Edge, Jake (18 May 2016). "The perils of federated protocols". LWN.net. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- Le Bihan, Michel (24 May 2016). "README.md". GitHub. LibreSignal. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- "Support for using Signal without Play Services · signalapp/Signal-Android@1669731". GitHub. Retrieved 2020-01-03.

- Marlinspike, Moxie (31 March 2016). "Reproducible Signal builds for Android". Open Whisper Systems. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- Marlinspike, Moxie (12 February 2013). "moxie0 commented Feb 12, 2013". GitHub. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- "Sign Your App". Android Studio. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- "About Code Signing". Apple Developer. Apple. 13 September 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- "Signal Android APK". Open Whisper Systems. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- "Surveillance Self-Defense. Communicating with Others". Electronic Frontier Foundation. 2014-10-23.

- SPIEGEL Staff (28 December 2014). "Prying Eyes: Inside the NSA's War on Internet Security". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- "Presentation from the SIGDEV Conference 2012 explaining which encryption protocols and techniques can be attacked and which not" (PDF). Der Spiegel. 28 December 2014. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- Eddy, Max (11 March 2014). "Snowden to SXSW: Here's How To Keep The NSA Out Of Your Stuff". PC Magazine: SecurityWatch. Retrieved 2014-03-16.

- "The Virtual Interview: Edward Snowden - The New Yorker Festival". YouTube. The New Yorker. 11 October 2014. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- Cameron, Dell (6 March 2015). "Edward Snowden tells you what encrypted messaging apps you should use". The Daily Dot. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- Yuhas, Alan (21 May 2015). "NSA surveillance powers on the brink as pressure mounts on Senate bill – as it happened". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- Beauchamp, Zack (21 May 2015). "The 9 best moments from Edward Snowden's Reddit Q&A". Vox Media. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- Barrett, Brian (25 February 2016). "Apple Hires Lead Dev of Snowden's Favorite Messaging App". Wired. Condé Nast. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- Nakashima, Ellen (22 September 2015). "ACLU calls for encryption on Capitol Hill". The Washington Post. Nash Holdings LLC. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- Macleod-Ball, Michael W.; Rottman, Gabe; Soghoian, Christopher (22 September 2015). "The Civil Liberties Implications of Insecure Congressional Communications and the Need for Encryption" (PDF). Washington, DC: American Civil Liberties Union. pp. 5–6. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- Whittaker, Zack (16 May 2017). "In encryption push, Senate staff can now use Signal for secure messaging". ZDNet. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- Wyden, Ron (9 May 2017). "Ron Wyden letter on Signal encrypted messaging". Documentcloud. Zack Whittaker, ZDNet. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- Bilton, Nick (26 August 2016). "How the Clinton Campaign Is Foiling the Kremlin". Vanity Fair. Condé Nast. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- Blake, Andrew (27 August 2016). "Democrats warned to use encryption weeks before email leaks". The Washington Times. The Washington Times, LLC. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- "EU Commission to staff: Switch to Signal messaging app". Politico EU. 20 February 2020.

- Molla, Rani (2020-06-03). "From Citizen to Signal, the most popular apps right now reflect America's protests". Vox. Retrieved 2020-06-07.

- "Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey says download Signal as US protests gain steam". The Economic Times. Bennett, Coleman & Co. Ltd. Indo-Asian News Service. 5 June 2020. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Lee, Timothy B. (2020-07-08). "Hong Kong downloads of Signal surge as residents fear crackdown". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- "How to share documents and news tips with Washington Post journalists". Washington Post. Retrieved 2020-06-05.

- Hoyland, Luke (2016-09-19). "How to contact the Guardian securely". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-06-05.

- "Tips". The New York Times. 2016-12-14. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-06-05.

- "WSJ.com Secure Drop". www.wsj.com. Retrieved 2020-06-05.

- Cox, Joseph (19 December 2016). "Signal Claims Egypt Is Blocking Access to Encrypted Messaging App". Motherboard. Vice Media LLC. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- Marlinspike, Moxie (21 December 2016). "Doodles, stickers, and censorship circumvention for Signal Android". Open Whisper Systems. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- Greenberg, Andy (21 December 2016). "Encryption App 'Signal' Fights Censorship with a Clever Workaround". Wired. Condé Nast. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- "SignalServiceNetworkAccess.java". GitHub. Open Whisper Systems. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- Frenkel, Sheera (2 January 2018). "Iranian Authorities Block Access to Social Media Tools". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- "Domain Fronting for Iran #7311". GitHub. 1 January 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- Brandom, Russell (2 January 2018). "Iran blocks encrypted messaging apps amid nationwide protests". The Verge. Vox Media. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- Marlinspike, Moxie (1 May 2018). "A letter from Amazon". signal.org. Open Whisper Systems. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- Gallagher, Sean (2 May 2018). "Amazon blocks domain fronting, threatens to shut down Signal's account". Ars Technica. Condé Nast. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- Parrelli, Greyson (4 April 2019). "Attempt to resolve connectivity problems for some users". GitHub. Signal Messenger LLC. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- O'Neill, Patrick (3 January 2017). "How Tor and Signal can maintain the fight for freedom in Trump's America". CyberScoop. Scoop News Group. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- Timm, Trevor (8 December 2016). "Freedom of the Press Foundation's new look, and our plans to protect press freedom for 2017". Freedom of the Press Foundation. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- "Signal". Freedom of the Press Foundation. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- "TextSecure". Knight Foundation. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- "Moxie Marlinspike". Shuttleworth Foundation. Archived from the original on 15 November 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- "Open Whisper Systems". Open Technology Fund. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- "Signal Technology Foundation". Nonprofit Explorer. Pro Publica Inc. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

Bibliography

- Cohn-Gordon, Katriel; Cremers, Cas; Dowling, Benjamin; Garratt, Luke; Stebila, Douglas (25 October 2016). "A Formal Security Analysis of the Signal Messaging Protocol" (PDF). Cryptology ePrint Archive. International Association for Cryptologic Research (IACR).

- Frosch, Tilman; Mainka, Christian; Bader, Christoph; Bergsma, Florian; Schwenk, Jörg; Holz, Thorsten (March 2016). How Secure is TextSecure?. 2016 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&P). Saarbrücken, Germany: IEEE. pp. 457–472. doi:10.1109/EuroSP.2016.41. ISBN 978-1-5090-1752-2.

- Rottermanner, Christoph; Kieseberg, Peter; Huber, Markus; Schmiedecker, Martin; Schrittwieser, Sebastian (December 2015). Privacy and Data Protection in Smartphone Messengers (PDF). Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Information Integration and Web-based Applications & Services (iiWAS2015). ACM International Conference Proceedings Series. ISBN 978-1-4503-3491-4. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- Schröder, Svenja; Huber, Markus; Wind, David; Rottermanner, Christoph (18 July 2016). When Signal hits the Fan: On the Usability and Security of State-of-the-Art Secure Mobile Messaging (PDF). Proceedings of the 1st European Workshop on Usable Security (EuroUSEC ’16). Darmstadt, Germany: Internet Society (ISOC). ISBN 978-1-891562-45-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 August 2016. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- Unger, Nik; Dechand, Sergej; Bonneau, Joseph; Fahl, Sascha; Perl, Henning; Goldberg, Ian Avrum; Smith, Matthew (2015). SoK: Secure Messaging (PDF). Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy. IEEE Computer Society's Technical Committee on Security and Privacy. pp. 232–249. doi:10.1109/SP.2015.22.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Signal (software). |

- Official website

- How to: Use Signal for Android by the Electronic Frontier Foundation

- How to: Use Signal on iOS by the Electronic Frontier Foundation