Sigismund Rákóczi

Sigismund Rákóczi (Hungarian: Rákóczi Zsigmond; 1544 – 5 December 1608) was Prince of Transylvania from 1607 to 1608. He was the son of János Rákóczi, a lesser nobleman with estates in Upper Hungary. Sigismund began a military career as the sword-bearer of the wealthy Gábor Perényi in Sárospatak. After Perényi died in 1567, Sigismund served in the royal fortresses of Eger and Szendrő. The royal chamber mortgaged him several estates to compensate him for unpaid salaries. He received Szerencs in 1580, which enabled him to engage in the lucrative Tokaji wine trade. He took possession of the large estates of András Mágóchy's minor sons as their guardian, and the second husband of their mother Judit Alaghy, in 1587.

| Sigismund Rákóczi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Prince of Transylvania | |

| Reign | 1607–1608 |

| Predecessor | Stephen Bocskai |

| Successor | Gabriel Báthory |

| Born | 1544 Felsővadász, Hungary |

| Died | 5 December 1608 (aged 63–64) Felsővadász, Hungary |

| Burial | 21 January 1609 |

| Spouse | Judit Alaghy Anna Gerendi Borbála Telegdy |

| Issue | Erzsébet George I Rákóczi Zsigmond Rákóczi Paul Rákóczi |

| Father | János Rákóczi |

| Mother | Sára Némethy |

| Religion | Calvinism |

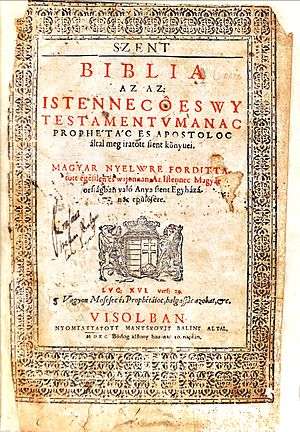

Sigismund was made the captain of the important stronghold of Eger on 29 June 1588. Rudolph I, King of Hungary, granted him the title of baron on 28 August. Sigismund rose to fame after he routed the united forces of three Ottoman beys (captains) near Szikszó on 8 October. He also helped the Calvinist pastor, Gáspár Károli, publish the Hungarian translation of the Bible (the so-called Vizsoly Bible). He renounced the captaincy in 1590 or 1591 because the royal treasury had not provided enough funds to finance the management of the fortress. Sigismund was a successful commander of the royal army during the first decade of the Long Turkish War, which broke out in 1593.

He continued to provide loans to the royal treasury which enabled him to seize new estates, but these were frequently pillaged both by Tatar marauders or unpaid mercenaries, especially after 1599. The royal chamber made attempts to seize his estates after 1602. Sigismund, who was suffering from an attack of gout, withdrew to his domains along the Polish-Hungarian border. After Stephen Bocskai rose up against Rudolph I in October 1604. Sigismund tried to mediate a reconciliation, but six months later he joined Bocskai who made him governor of Transylvania with limited authority on 14 August 1606.

Although Bocskai named Bálint Drugeth (Sigismund's former son-in-law) his successor in his last will, the Diet of Transylvania elected Sigismund prince on 12 February 1607. Drugeth abandoned his claim to Transylvania, but Gabriel Báthory (who was related to former princes) secured the support of the Hajdús (irregular soldiers) against Sigismund for himself. To avoid a new civil war, Sigismund abdicated in favor of Báthory on 5 March 1608. Sigismund returned to Upper Hungary and tried to seize command of the royal army in the region, but he died. His acquisition of large estates made his descendants the wealthiest magnates of Royal Hungary.

Childhood

Sigismund was born to János Rákóczi and Sára Némethy in Felsővadász in 1544.[1][2] His father held small estates in Abaúj and Zemplén Counties.[3] János Rákóczi was vice-ispán (or deputy head) of Zemplén County in 1551.[4] Sigismund was first mentioned in his father's charter on 22 December 1550.[5] In the charter, János Rákóczi made a complaint against Gábor Perényi, the lord of Sárospatak, who had captured one of the Rákóczis' villages, Selyeb.[6]

Sigismund attended school at his father's insistence, according to the address that István Miskolczi Csulyak gave at his funeral.[5] Historian András Szabó believes Sigismund was most probably educated in the Protestant schools at Sajószentpéter and Sárospatak.[7] He could write and read Latin.[7] He often read the Bible and the works of Roman historians until the end of his life.[7] After his father died in 1561, Sigismund decided on a military career.[7]

Career

Beginnings

Sigismund became the sword-bearer of the wealthy Gábor Perényi in Sárospatak.[7] He fought in the army of Lazarus von Schwendi, the supreme commander of Upper Hungary, during the siege of Tokaj in 1565.[8] After Perényi died in 1567, Sigismund went to serve in the stronghold of Eger.[9] According to a 17th-century family chronicle, Sigismund accompanied Gáspár Bekes to Transylvania and fought by his side in the Battle of Kerelőszentpál in 1575.[10] In the same year Sigismund was adopted by the widowed Júlia Zsoldos who willed him Csenyéte, Irota and Szakácsi.[11]

At an unspecified date between 1573 and 1577, Sigismund was transferred to the fortress of Szendrő.[10][12] As commander of the Hungarian forces, he participated in many skirmishes against Ottoman soldiers garrisoned in nearby fortresses.[10][12] For instance, after the bey (captain) of Fülek plundered the fair at Szikszó, Sigismund and the deputy-captain of Kassa (now Košice in Slovakia), Bálint Prépostváry, joined forces and defeated the retreating Ottomans at Vadna on 11 November 1577.[13]

Sigismund often mentioned in his letters that he and his soldiers had not received their salaries.[14] To compensate him for the unpaid amounts, the royal chamber mortgaged several estates to him.[15] He first received Felsőlenke and Sajószentkirály (now Lenke and Kráľ in Slovakia) in the late 1570s.[15] Szerencs was mortgaged to him for 4,000 florins in 1580.[15] Szerencs was located near the Tokaj wine region, enabling Sigismund to trade in wine.[16][17] This lucrative business made him a wealthy man by the late 1580s.[16] He erected a new castle in Szerencs, which became the center of his domains.[18]

His prestige also increased.[19] Lesser noblemen began regarding him as an able protector.[11] Rudolph I, King of Hungary, tasked him with the collection of the two-florin extraordinary tax payable by each peasant households in Gömör County in 1582, and in Borsod County in 1584.[19] He was made the captain of Szendrő in 1585.[12] By that time Sigismund, like most of his peers in Upper Hungary, had converted from Lutheranism to Calvinism.[20]

The dying[7] Gáspár Mágóchy made Sigismund the guardian of András Mágóchy's sons in 1587.[11] András (who was the wealthy Gáspár's nephew) had died in the summer of 1586.[7] His orphaned sons inherited large estates in Bereg, Szepes and Torna Counties.[21] Sigismund wrote a poem in Hungarian in Munkács on 25 May, praising God and seeking his protection.[22] In the poem, he also referred to his obligation to protect the orphans and widows.[7] Before the end of the following month, he married András Mágóchy's widow (the mother of his wards), Judit Alaghy.[22] He was the representative of the untitled noblemen on the committee, set up at the demand of the Diet of Hungary in 1588, to review the administration of royal revenues in Upper Hungary.[23] The committee members visited all the important centers of the region, but their report was ignored by the royal court.[23]

Magnate

Being the guardian of the minor Mágóchys, and the husband of their mother, Sigismund took possession of their properties, including the domain of Munkács.[11] He employed knezes who gathered colonists to establish new villages on his new estates.[24] He reinvested his income, either lending money to the royal treasury, or buying new landed property.[25]

Sigismund was made the captain of the fortress of Eger in 1588 at the initiative of the king's brother, Ernest.[26] The Diet had demanded the appointment of a Hungarian nobleman to command Eger since 1580, and his loyalty to the king was unquestionable.[27] Count Nogarola, the supreme commander of Upper Hungary, installed Sigismund on 29 June.[28] By that time, the former villages of the fortress had either been captured by the Ottomans, or mortgaged by Sigismund's predecessor, Krsto Ungnad.[29] Sigismund could finance the administration of the fortress from the revenues of the Bishopric of Eger, and from subsidies from the royal treasury.[29][30] At his appointment, he was commander of a garrison of over 500 horsemen and 450 foot soldiers; by the end of 1590, he was the head of 440 horsemen and 830 foot soldiers.[29]

As captain of Eger, he also became the ispán (head) of Heves and Borsod Counties.[29] Rudolph I granted him the rank of baron on 28 August 1588, raising him from the masses of untitled noblemen.[31] Before long, he had to face an Ottoman attack against Szikszó.[30] He first routed the troops of the bey of Szolnok on 2 October.[32] His son, George, would later say, Sigismund always relied on espionage to prevent sudden attacks.[32] After reinforcements from Kassa, Szendrő and Tokaj joined his troops, Sigismund hurried to Szikszó and routed the united army of three beys on 8 October.[33][34] His victory was celebrated by the whole kingdom, and in Vienna and Prague.[35] The minstrel György Tardi composed a poem to commemorate it.[36]

The Hungarian translation of the Bible, known as the Vizsoly Bible, completed by the Calvinist pastor Gáspár Károli, was printed under the auspices of Sigismund between February 1589 and July 1590.[37] He also financed the education of young men at the universities of Heidelberg and Wittenberg.[38] After finishing their studies, he employed them as Calvinist priests on his estates.[38] He had a good relationship with some Catholic prelates.[39] For instance, the provost (head) of the Eger Chapter borrowed 150 florins from him in 1589.[40] He also employed Orthodox priests for his Rusyn serfs.[41] However, he imprisoned the Orthodox bishop of Munkács who had filed a complaint against him at the royal court for unknown reasons.[41]

Sigismund continued the restoration the fortress of Eger which had begun in 1569.[36] He redeemed at least four villages in the royal estates centered around the fortress which had been mortgaged by his predecessors.[36] However, he found his position onerous because the royal treasury was unwilling to pay all the expenses.[42] He announced that he wanted to renounce his captaincy of the fortress on 12 March 1590, but his successor, Bálint Prépostváry, was only appointed on 15 July 1591.[42] He moved to Munkács and restored the castle.[43] He retained the guardianship of his stepsons after his wife died in July 1591.[42] In an attempt to seize the guardianship, his stepsons' cousin, Magdolna Káthay, filed a lawsuit against Sigismund stating that he had been negligent, but she lost the case.[44] Sigismund married his second wife, Anna Gerendi, before 15 July 1592.[45]

Long Turkish War

The Diet of Hungary voted an extraordinary tax to finance the defense of Slavonia and Croatia against the Ottomans in early 1593.[46] The Diet appointed Sigismund to collect the tax in Upper Hungary.[46] After the Ottoman Grand Vizier, Koca Sinan Pasha, invaded Transdanubia, rumours about his plan to transform Upper Hungary into a voivodate (vassal state) were spreading.[47] Sigismund urged the influential Nicholas Pálffy to persuade Rudolph I to launch a counter-invasion against the Ottomans without delay.[48] He also suggested that Transylvania, Moldavia and Wallachia should be included in an anti-Ottoman coalition.[48]

When the royal army broke into Ottoman territory in October, Sigismund was one of its commanders.[49] After routing an Ottoman army at Romhány on 14 November, the royal troops laid siege to the important Ottoman fortress of Fülek.[50][51] Since Sigismund was famed for his reliability, the defenders approached him to discuss the terms of their surrender.[50] They and their families were allowed to leave the fortress on 27 November.[50][51] The royal army also captured the nearby Ottoman fortresses before the end of 1593.[50][51] The capture of Fülek reinforced Sigismund's reputation.[52]

He joined Simon Forgách who led a contingent of the royal army against the important Ottoman fortress of Hatvan in early 1594.[52] They defeated the Pasha (governor) of Buda at Tura on 1 May,[51] but they could not capture Hatvan.[53] Crimean Tatars broke into Upper Hungary to assist the Ottoman forces, plundering the villages near Munkács during their march.[53] Sigismund was made a member of the royal council around 1595, thus becoming the only councillor who did not hold a high office of the realm.[54] He never attended the meetings of the royal council.[55]

Sigismund's second wife died in 1595.[56] He married Borbála Telegdy in May 1596[57] As guardian of her daughter, Zsuzsa Chapy, he took possession of her estates in Eszeny (now Eseny in Ukraine) and Parnó (now Parchovany in Slovakia).[58][59] According to a census of the peasant households, Sigismund held estates in seven counties in 1596.[60] The census also shows that many villages were destroyed during the war.[60] For instance, about 45% of the households in Bereg County disappeared between 1588 and 1596.[60]

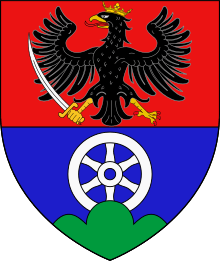

Rudolph I's brother, Maximilian, launched a campaign against Ottoman territories in the summer of 1596.[61] Sigismund joined the royal army and participated in the capture of Vác and Hatvan.[62] He also provided a loan of 3,000 thalers to Maximilian.[63] An attack of gout paralysed him shortly before the Battle of Mezőkeresztes, which ended with the catastrophic defeat of the united armies of Maximilian and Sigismund Báthory, prince of Transylvania on 28 October.[63] Rudolph I granted Sigismund a new coat-of-arms to reward him for his military service and financial support on 27 May 1597.[63] The new escutcheon (shield) depicted an eagle (instead of the Rákóczis' former raven), and supplemented the Rákóczis' traditional wheel with a mountain with three peaks.[64]

Rudolph I appointed commissioners to take possession of Transylvania in early 1598.[65] Sigismund sent reinforcements to Transylvania to assist the commissioners.[66] He was made the commander of the Hungarian troops in Upper Hungary, but his relationship with the supreme commander, Giorgio Basta, became tense.[67] Sigismund sent letters to Basta, complaining that unpaid mercenaries had destroyed his estates.[67] Basta accused him first of having failed to pay his troops' salaries, then of conspiring against the monarch.[67] Crimean Tatars pillaged many villages in Upper Hungary in the summer of 1599, which contributed to his loss of popularity with the noblemen.[68] He was tasked with the mustering of troops without the support of the Diet.[69] Unpaid mercenaries also often pillaged his estates.[70] Almost 40% of the houses were destroyed in Munkács between 1598 and 1601, and 20% of his villages in Zemplén County became depopulated during the same period.[71]

Sigismund could still loan money to the royal treasury and seize new estates.[72][73] The treasury could only finance Basta's campaign in Transylvania with Sigismund's loans.[74] Tarcal in the Tokaji wine region was mortgaged to him in 1599.[73] Prince Janusz Ostrogski sold the domain of Makovica in Sáros County (at present-day Zborov in Slovakia) to him for 80,000 florins in August 1601.[75][76] The domain was Sigismund's own property, in contrast with most of his other estates that he held either as a security for the loans he had provided to the royal treasury or as his wards' guardian.[75][77] Sigismund promised Ostrogski that he would not force the Orthodox and Catholic serfs to convert to Calvinism.[78] The castle of Makovica controlled an important route between Hungary and Poland.[77] After seizing it, Sigismund often delivered wine to Poland without paying custom duties, according to a letter of Rudolph I.[79]

Sigismund's ward, Ferenc Mágóchy reached the age of majority in 1602.[80] Mágóchy's relatives persuaded him to demand an account from Sigismund, and the royal chamber supported him.[81] Ostrogski also filed a lawsuit against Sigismund, stating that he had failed to complete the terms of the transfer of the domain of Makovica.[82] Always being in need of funds, the royal chamber also wanted to seize Sigismund's estates.[83] Royal officials obtained three of Sigismund's letters in which he complained about the state of affairs in Hungary, and mentioned his correspondence with Ottoman beys about the redemption of prisoners of wars.[84][82] Rudolph I's brother, Matthias, wanted to summon Sigismund to the Diet, but the royal councillors stood by Sigismund.[84] Sigismund and Mágóchy reached a compromise in early 1603.[81] Mágóchy received the domain of Munkács, and Sigismund promised to pay 30,000 florins and to give two villages to him,[81] but he failed to keep his promise.[85]

The Diet assembled in Pressburg (now Bratislava in Slovakia) on 3 February 1604.[86] Sigismund did not attend the Diet because he had fallen ill.[83] At his request, the delegates of the Eger Chapter visited him in Makovica and issued a certificate proving that he was unable to move.[83][87] After the Diet was dissolved, Rudolph I arbitrarily promulgated a decree that prohibited the Diet from discussing religious issues.[88] The Lutheran and Calvinist noblemen and burghers of Upper Hungary assembled at Gálszécs (now Sečovce in Slovakia) on 8 September, demanding the withdrawal of the decree.[89] Sigismund attended the meeting, but soon returned to Makovica.[90]

Bocskai's supporter

Stephen Bocskai rose up against Rudolph I in Partium in October 1604.[89] Two captains of the Hajdús who supported Bocskai, Balázs Liptai and Balázs Németi, urged Sigismund to join them in a letter in early November.[91] Sigismund remained in Makovica, but exchanged letters with Bocskai.[91] He sent his eldest son, George, to Bocskai who was in Kassa (now Košice in Slovakia).[91] Cooperating with István Csáky, Sigismund tried to mediate a compromise between Bocskai and the monarch, fearing that the Ottomans would take advantage of the civil war in Hungary.[92] Giorgio Basta was convinced that Sigismund actually wanted to secure the Principality of Transylvania and the rule of Upper Hungary for Bocskai.[92]

Bocskai's supporters assembled at Rákóczi's estate, Szerencs, and acclaimed him prince of Hungary on 20 April 1605.[93][94] A week later, Sigismund and his former son-in-law, Bálint Drugeth, went to see the wealthy Stephen Báthory at Nagyecsed and convinced him to join Bocskai.[95] Suffering from attacks of gout, Sigismund stayed mostly at Bocskai's court in Kassa during the following months.[95]

Transylvania

Governor

Sigismund accompanied Bocskai (who had already been elected prince of Transylvania) to Transylvania in August 1605.[96] With the consent of the Diet of Transylvania, Bocskai made him governor to administer the principality on 14 September.[97][93] Sigismund could not threaten Bocskai's rule because he did not have allies either in the Ottoman Empire or in Transylvania.[98] Bocskai's brother-in-law, Gábor Haller, administered the royal treasury independently of Sigismund, and János Petki, the commander of the Székelys, also received direct instructions from Bocskai.[99][100] Sigismund took up his seat in Gyulafehérvár (now Alba Iulia in Romania).[97]

Crimean Tatars moved into Transylvania to fight against Bocskai's opponents in late September, but Sigismund convinced them to withdraw without a fight.[101] Déva (now Deva in Romania), the last fortress to resist Bocskai in Transylvania proper, surrendered on 11 November.[101] Sigismund bought the domains of Szádvár and Sáros' fortresses (now Šariš Castle in Slovakia) from István Csáky's widow, but he could not pay the purchase price.[75] He prohibited the Sabbatarians from holding assemblies in Udvarhelyszék on 7 March 1606.[102][103] He did not prevent the Diet from adopting laws which enabled the noblemen to put Székely commoners into servitude.[102] The adventurer György Rácz tried to stir up the Székelys against Bocskai with the support of Radu Șerban, Prince of Wallachia, but Sigismund had Rácz captured on 7 June.[104][105]

On 23 June 1606, the Treaty of Vienna confirmed the autonomous status of the Principality of Transylvania under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire.[106] Bocskai died on 29 December, naming Bálint Drugeth his heir in his last will, although the Treaty of Vienna also confirmed the right of the Diet of Transylvania to elect Bocskai's successor.[107] The Diet of Transylvania stated that Bocskai's death had put an end to Sigismund's appointment, but confirmed his position as governor on 22 January 1607.[108][109]

György Thurzó noted that most Transylvanian noblemen were also willing to elect Sigismund prince, although Sigismund was not the only candidate.[108] The young Gabriel Báthory had laid claim to the principality in a letter to the Ottoman grand vizier already on 2 January 1607; other noblemen supported Pál Nyáry, Boldizsár Korniss, Boldizsár Szilvási or Gabriel Bethlen.[110] Drugeth and Báthory were Sigismund's chief rivals, but they failed to rush to Transylvania to secure their election.[111] The Diet also wanted to demonstrate its right to freely elect the prince, without recognizing the right of a prince to designate his successor or the Báthorys' claim to hereditary rule.[112]

Prince

The Diet again assembled to elect the new prince at Kolozsvár on 8 February 1607.[113] In accordance with Bocskai's last will, Sigismund proposed Bálint Drugeth (his former son-in-law), but the delegates of the Three Nations proclaimed Sigismund prince on 12 February.[111][113] Stating that he was old and suffering from gout, Sigismund did not want to accept his election, but the delegates persuaded him to take the princely oath.[113] Sigismund's election was the only occasion when the Diet of Transylvania could freely elect a monarch during the history of the principality.[114][115]

Gabriel Báthory accepted Sigismund's election, but he also demanded the restoration of the estates confiscated from his family in 1595.[116] Drugeth seized Huszt and Kővár (now Khust in Ukraine and Remetea Chioarului in Romania, respectively) on the border.[117] Sigismund wrote to Rudolph I's brother, Matthias, asking him to order Drugeth to withdraw from the two fortresses.[118][119] The Ottoman grand vizier, Kuyucu Murad Pasha, had confirmed Drugeth as Bocskai's successor on 18 January, but his envoy, Mustafa, modified the ahidnâme (diploma) after he learned of Sigismund's election.[118][120][121] The altered document, which confirmed Sigismund's election, was presented on 22 February.[109] To secure Murad Pasha's support, Sigismund offered to withdraw the Transylvanian troops from two important border fortresses, Lippa and Jenő (now Lipova and Ineu in Romania), but the grand vizier did not accept the offer.[121]

Rudolph I did not acknowledge Sigismund's election.[122] The noblemen of Upper Hungary assembled at Rozgony (now Rozhanovce in Slovakia) and urged Sigismund to abdicate in favor of Drugeth on 19 April.[123] Fearing an attack by Drugeth, Sigismund moved to the fortress of Fogaras (now Făgăraș in Romania) in southern Transylvania.[123] However, Rudolph I, who regarded Transylvania as a realm of the Holy Crown of Hungary, did not support Drugeth.[124] Instead, according to contemporaneous rumours, Rudolph was planning to restore Transylvania to Sigismund Báthory.[124] Sigismund Rákóczi invited Drugeth to come to Transylvania.[124] After their meeting, Drugeth did not make any further attempts to assert his claim to the principality, but retained Huszt and Kővár.[124][125]

The Diet of Transylvania did not restore the estates to Gabriel Báthory in June.[125] In addition it ordered the expulsion of the Jesuits from the principality, which outraged the Catholic noblemen.[125][126] Gabriel Báthory promised to promote the interests of the Catholics if he were elected prince.[127] The Hajdús, who had not received their salary after Bocskai's death, rose up in rebellion in October 1607.[128] They decided to place Bálint Drugeth on the throne.[128] Ali Pasha, the Ottoman governor of Buda, supported their movement.[129][130] Sigismund entered into negotiations with Gabriel Báthory, who promised to pay the purchase price of the domains of Szádvár and Sáros on Sigismund's behalf if he abdicated.[131][132] Drugeth refused to ally himself with the Hajdús, enabling Gabriel Báthory to make a treaty with them on 6 February 1608.[133] Báthory promised that he would make Catholic and Unitarian noblemen royal councillors.[127] To avoid a new civil war, Sigismund abdicated at the Diet in Kolozsvár on 5 March 1608.[134][135]

Last months

Sigismund and his wife left Kolozsvár for Upper Hungary on 7 March 1608.[136] Gabriel Báthory was elected prince of Transylvania on the same day.[133] Sigismund visited Szádvár on his way back to Makovica.[136] He provided new loans to the commanders of the royal army who had been unable to finance their fights against the rebellious Hajdús.[137] The Hajdús pillaged Sigismund's house at Felsővadász.[138]

Sigismund tried to seize the supreme commandership of Upper Hungary, but the most influential royal councillors did not support him.[139] He planned to go to Pressburg to be present at the Diet which had been convoked to elect Matthias II as King of Hungary, but he fell seriously ill.[140] He died in Felsővadász on 5 December 1608.[141] He was buried in Szerencs on 21 January 1609.[142]

Sigismund had the most dazzling career among his contemporaries in Hungary.[143] He was born as a lesser nobleman and died as a magnate, showing that he had been a "man of considerable talent," according to historian Katalin Péter.[121] His acquisition of dozens of estates made him one of the wealthiest landowners of Royal Hungary, and established the basis of his descendants' power in the 17th century.[143] Although he ruled Transylvania for less than two years, his short rule enabled his son, George I, to seize Transylvania in 1630.[143]

Family

| Ancestors of Sigismund Rákóczi[141] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sigismund's first wife, Judit Alaghy, was the daughter of János Alaghy, the lord of Regéc.[57] She inherited parts of her father's estates, including Tállya and Abaújszántó.[57] She gave birth to Sigismund's first child, Erzsébet in 1588.[144] When Judit fell seriously ill in the spring of 1591, Sigismund took her to the hospital in Sandomierz in Poland where she died on 12 July.[57][31] Erzsébet Rákóczi was given in marriage to Bálint Drugeth in 1602.[74] She died two years later.[145]

Sigismund's second wife, Anna Gerendi, was the daughter of the Sabbatarian Transylvanian nobleman, János Gerendi, and Kata Erdélyi.[146][58] Sigismund married the stepdaughter of his sister, Magdolna, because Gerendi was Magdolna's second husband.[57] Anna gave birth to three sons.[58] George, who was born in 1593, became Prince of Transylvania years after his father's death.[145][58] Sigismund, who was born in 1594 and died in 1620, did not make a career for himself.[145][58] Paul was born in 1595.[145] He was made judge royal of Hungary[145] in 1631. Anna died soon after the birth of her third son.[56]

Sigismund admitted that he had "loved women so much, that he could not live without them" in a letter addressed to his nephew, Lajos Rákóczi, a few months after Anna's death.[57][59] He proposed himself to the Catholic Borbála Telegdy, who was the widow of his late friend Kristóf Chapy.[56] They married in May 1596.[59] She survived Sigismund and converted his third son, Paul, to Catholicism.[57]

References

- Szabó 1986, p. 341.

- Hangay 1987, pp. 10, 225.

- Hangay 1987, pp. 6–10.

- Trócsányi 1979, p. 58.

- Hangay 1987, p. 13.

- Hangay 1987, pp. 12–13.

- Szabó 1986, p. 342.

- Hangay 1987, p. 16.

- Hangay 1987, p. 21.

- Szabó 1986, p. 344.

- Hangay 1987, p. 37.

- Hangay 1987, p. 225.

- Hangay 1987, p. 25.

- Hangay 1987, p. 27.

- Hangay 1987, p. 32.

- Hangay 1987, p. 33.

- Trócsányi 1979, p. 59.

- Hangay 1987, p. 34.

- Hangay 1987, p. 36.

- Hangay 1987, p. 77.

- Trócsányi 1979, p. 60.

- Szabó 1986, p. 345.

- Hangay 1987, p. 45.

- Hangay 1987, p. 40.

- Hangay 1987, p. 62.

- Hangay 1987, pp. 49–52.

- Hangay 1987, p. 49.

- Hangay 1987, p. 53.

- Trócsányi 1979, p. 62.

- Hangay 1987, p. 58.

- Hangay 1987, p. 226.

- Hangay 1987, p. 67.

- Hangay 1987, pp. 66, 73–74, 226.

- Trócsányi 1979, pp. 63–64.

- Hangay 1987, p. 76.

- Trócsányi 1979, p. 64.

- Hangay 1987, p. 84.

- Szabó 1986, p. 347.

- Hangay 1987, p. 80.

- Hangay 1987, pp. 80–81.

- Szabó 1986, p. 348.

- Hangay 1987, p. 90.

- Hangay 1987, p. 91.

- Hangay 1987, pp. 90–91.

- Hangay 1987, p. 95.

- Hangay 1987, p. 98.

- Hangay 1987, pp. 100–101.

- Hangay 1987, p. 101.

- Hangay 1987, p. 102.

- Hangay 1987, p. 103.

- Granasztói 1981, p. 413.

- Hangay 1987, p. 108.

- Hangay 1987, p. 109.

- Trócsányi 1979, p. 69.

- Trócsányi 1979, p. 70.

- Hangay 1987, p. 118.

- Szabó 1986, p. 346.

- Trócsányi 1979, p. 65.

- Hangay 1987, p. 119.

- Hangay 1987, p. 117.

- Hangay 1987, p. 111.

- Hangay 1987, pp. 111–112.

- Hangay 1987, p. 112.

- Hangay 1987, p. 113.

- Hangay 1987, pp. 120–122.

- Hangay 1987, p. 122.

- Hangay 1987, p. 124.

- Hangay 1987, pp. 126–127.

- Hangay 1987, p. 127.

- Hangay 1987, pp. 128–129.

- Hangay 1987, p. 129.

- Hangay 1987, p. 133.

- Trócsányi 1979, p. 67.

- Hangay 1987, p. 227.

- Trócsányi 1979, p. 68.

- Hangay 1987, pp. 139, 227.

- Hangay 1987, p. 139.

- Trócsányi 1979, pp. 68–69.

- Hangay 1987, p. 140.

- Hangay 1987, p. 143.

- Hangay 1987, p. 147.

- Trócsányi 1979, p. 72.

- Hangay 1987, p. 149.

- Hangay 1987, p. 148.

- Trócsányi 1979, p. 73.

- Granasztói 1981, p. 426.

- Trócsányi 1979, p. 74.

- Hangay 1987, p. 151.

- Granasztói 1981, p. 427.

- Hangay 1987, p. 153.

- Hangay 1987, p. 154.

- Hangay 1987, p. 156.

- Granasztói 1981, p. 429.

- Hangay 1987, p. 157.

- Hangay 1987, p. 158.

- Hangay 1987, p. 166.

- Hangay 1987, p. 167.

- Hangay 1987, pp. 167–168.

- Hangay 1987, p. 168.

- Trócsányi 1979, p. 76.

- Hangay 1987, p. 169.

- Hangay 1987, p. 170.

- Trócsányi 1979, p. 75.

- Granasztói 1981, p. 431.

- Trócsányi 1979, p. 81.

- Keul 2009, p. 158.

- Hangay 1987, pp. 175-176.

- Hangay 1987, p. 176.

- Granasztói 1981, p. 433.

- Hangay 1987, pp. 178-179.

- Keul 2009, p. 159.

- Péter 1994, p. 303.

- Hangay 1987, p. 180.

- Hangay 1987, p. 181.

- Trócsányi 1979, p. 86.

- Hangay 1987, pp. 182, 187.

- Hangay 1987, p. 182.

- Hangay 1987, p. 183.

- Trócsányi 1979, p. 90.

- Trócsányi 1979, p. 87.

- Péter 1994, p. 304.

- Hangay 1987, p. 186.

- Trócsányi 1979, p. 98.

- Trócsányi 1979, p. 99.

- Hangay 1987, p. 187.

- Trócsányi 1979, p. 92.

- Keul 2009, p. 160.

- Hangay 1987, p. 192.

- Hangay 1987, p. 193.

- Péter 1994, p. 305.

- Hangay 1987, p. 198.

- Trócsányi 1979, p. 103.

- Granasztói 1981, p. 435.

- Hangay 1987, pp. 198, 202.

- Trócsányi 1979, p. 107.

- Hangay 1987, p. 202.

- Hangay 1987, pp. 204–205.

- Hangay 1987, p. 207.

- Hangay 1987, pp. 212–216.

- Hangay 1987, pp. 219–220.

- Hangay 1987, p. 220.

- Hangay 1987, p. 222.

- Trócsányi 1979, p. 108.

- Hangay 1987, pp. 90, 221.

- Hangay 1987, p. 221.

- Hangay 1987, pp. 91–92.

Sources

- Granasztói, György (1981). "A három részre szakadt ország és a török kiűzése (1526–1698): 1557–1605". In Benda, Kálmán; Péter, Katalin (eds.). Magyarország történeti kronológiája, II: 1526–1848 [Historical Chronology of Hungary, Volume I: 1526–1848] (in Hungarian). Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 361–430. ISBN 963-05-2662-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hangay, Zoltán (1987). Erdély választott fejedelme: Rákóczi Zsigmond [Elected Prince of Transylvania: Sigismund Rákóczi]. Zrínyi Kiadó. ISBN 963-326-363-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Keul, István (2009). Early Modern Religious Communities in East-Central Europe: Ethnic Diversity, Denominational Plurality, and Corporative Politics in the Principality of Transylvania (1526–1691). Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-17652-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Péter, Katalin (1994). "The Golden Age of the Principality (1606–1660)". In Köpeczi, Béla; Barta, Gábor; Bóna, István; Makkai, László; Szász, Zoltán; Borus, Judit (eds.). History of Transylvania. Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 301–358. ISBN 963-05-6703-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Szabó, András (1986). "Rákóczi Zsigmond erdélyi fejedelem (1544-1608): Kiegészítések egy életrajzhoz [Sigismund Rákóczi, Prince of Transylvania (1544-1608): Addenda to a biography]". Történelmi Szemle (in Hungarian). 2: 341–350.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Trócsányi, Zsolt (1979). "Rákóczi Zsigmond (Egy dinasztia születése) [Sigismund Rákóczi (The birth of a dynasty)]". In Dankó, Imre (ed.). A debreceni Déri Múzeum Évkönyve [Annual of the Déri Museum of Debrecen] (in Hungarian). Déri Múzeum. pp. 57–113. ISSN 0133-8080.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Marek, Miroslav. "Genealogy of the Rákóczi family". genealogy.euweb.cz.

Sigismund Rákóczi Born: 1544 Died: 5 December 1608 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Stephen Bocskai |

Prince of Transylvania 1607–1608 |

Succeeded by Gabriel Báthory |