Siege of Kamacha

The siege of Kamacha by the Abbasid Caliphate took place in autumn 766, and involved the siege of the strategically important Byzantine fortress of Kamacha on the eastern bank of the Euphrates River, as well as a large-scale raid across eastern Cappadocia by a part of the Abbasid invasion army. Both enterprises failed, with the siege dragging on into winter before being abandoned and the raiding force being surrounded and heavily defeated by the Byzantines. The campaign was one of the first large-scale Abbasid operations against Byzantium, and is one of the few campaigns of the Arab–Byzantine wars for which detailed information survives, although it is barely mentioned in Arabic or in Byzantine sources.

Background

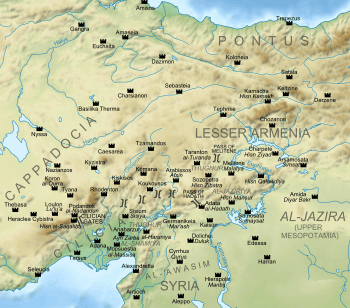

Following the Umayyad civil wars of the 740s and the turmoil of the Abbasid Revolution, the Byzantines under Emperor Constantine V (reigned 741–775) regained the initiative on their eastern border and pursued an aggressive, but limited, strategy towards the Caliphate: rather than attempting a reconquest, through his deportation of frontier populations and his obstruction of Muslim fortification efforts, Constantine pursued the establishment of a permanent no-man's land between Byzantine and Muslim domains that would shield Asia Minor and obstruct Muslim raids against it.[1][2] Among the fortresses captured by the Byzantines in 754/755, was Kamacha (in Arabic: Hisn Kamkh).[3][4] Strategically located on a plateau above the banks of the Upper Euphrates, it lay on the easternmost extremities of Byzantine territory, and since its first capture by the Arabs in 679 it had changed hands many times.[5]

After the overthrow of the Umayyads, the new Abbasid regime quickly resumed their predecessor's attacks on the Byzantine Empire, the first being recorded in 756. Despite a few successes on both sides, including a major Arab victory in 760, the five years after that were relatively tranquil, with Constantine V engaged in his wars against the Bulgars and the Abbasid Caliphate focused on subduing revolts and countering Khazar incursions.[1][4][6]

Siege

In early 766 a prisoner exchange took place between the two states in western Cilicia, followed by a resumption of large-scale hostilities. In August 766, a large Abbasid army, comprising many different national contingents, under al-Hasan ibn Qahtaba and al-Abbas ibn Muhammad, the brother of Caliph al-Mansur (r. 754–775), invaded Byzantine territory from Upper Mesopotamia and made for Kamacha.[7] The campaign is dealt with briefly by Muslim historians such as al-Tabari, but is fully recorded in a contemporary Syriac Christian source, the so-called Zuqnin Chronicle, written by a monk of the Zuqnin Monastery near Amida.[8]

The Abbasid force met no resistance as they pillaged their way to the fortress. Once there, they began constructing siege engines and trying to fill its moat, but their progress was obstructed by the defenders’ own artillery. Then the Abbasids tried to launch a surprise night attack against a section of the fortress where there were no walls; the attack was repelled by the Byzantines, who hurled great logs, weighted with stones, against them.[9]

At this point, the Muslims divided their forces: the bulk of the army, under Abbas, remained at Kamacha to continue the siege, while the remainder (an obviously exaggerated force of 50,000 according to the Zuqnin chronicler) was sent to raid further into Byzantine territory and pillage. The siege continued through the autumn, and the Arabs, who customarily did not take along many provisions, began suffering from lack of supplies. To solve their supply problems, they established a market for merchants from Mesopotamia and elsewhere. In the end, with winter approaching, Abbas was forced to raise the siege and retreat south, burning the large market-place to prevent it from falling into Byzantine hands.[4][9]

The other half of the army fared worse: lacking guides with local knowledge, it lost many men to hunger and thirst in its wanderings through the deserted borderlands, before reaching the fertile plains of Cappadocia around Caesarea. After looting the area, they turned south and made for Syria. On their way, they were detected by a Byzantine force of 12,000, which swiftly called in reinforcements. The Byzantines then attacked at night, defeating the Abbasid army and recovering its loot. The surviving Abbasid troops scattered, with some following one of their leaders, Radad, to Malatya, and some 5,000 under Malik ibn Tawq finding refuge in Qaliqala. It was from the latter group that the Zuqnin chronicler drew his information.[4][9] The campaign is one of the few such border raids to be known in detail, and, as the Islamic historian Hugh N. Kennedy comments, "We probably get much closer to the reality of frontier warfare, with its confusions, hardships and failures, in this account than in the brief and sanitised versions provided by the Arabic historians."[9]

Aftermath

Despite this failure, Arab pressure gradually began to mount, especially after the sack of Laodicea Combusta in 770. The Byzantines were still capable of major counterstrokes and scored a few victories in the field, but in 782 the Caliphate mobilized its resources and launched a massive invasion under the Abbasid heir-apparent, Harun al-Rashid (r. 786–809), which forced the Empire into conceding a three-year truce and the payment of a heavy tribute. When warfare resumed in 785, and until the outbreak of the Abbasid civil war following Harun's death in 809, the Abbasids established and maintained a clear military supremacy, although vigorous Byzantine resistance prohibited any plans for outright conquest.[10][11] Kamacha itself was surrendered to the Arabs by its Armenian garrison in 793, only to be recovered by the Byzantines in the years following Harun's death. It fell again to Muslim hands in 822, and was not finally retaken by the Byzantines until 851.[12]

References

- Rochow 1994, pp. 74–78.

- Lilie 1976, pp. 164–165, 178–179.

- Lilie 1976, p. 165.

- Brooks 1923, p. 122.

- ODB, p. 1097.

- Lilie 1976, p. 170.

- Kennedy 2001, p. 106.

- Kennedy 2001, pp. 106–107.

- Kennedy 2001, p. 107.

- Lilie 1976, pp. 166–168, 170–182.

- Brooks 1923, pp. 122–127.

- Brooks 1923, pp. 125, 127, 131.

Sources

- Brooks, E. W. (1923). "Chapter V. (A) The Struggle with the Saracens (717–867)". The Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. IV: The Eastern Roman Empire (717–1453). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 119–138.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504652-8.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2001). The Armies of the Caliphs: Military and Society in the Early Islamic State. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-45853-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lilie, Ralph-Johannes (1976). Die byzantinische Reaktion auf die Ausbreitung der Araber. Studien zur Strukturwandlung des byzantinischen Staates im 7. und 8. Jhd (in German). Munich: Institut für Byzantinistik und Neugriechische Philologie der Universität München. OCLC 797598069.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rochow, Ilse (1994). Kaiser Konstantin V. (741–775). Materialien zu seinem Leben und Nachleben (in German). Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. ISBN 3-631-47138-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)