Siamanto

Atom Yarjanian (Armenian: Ատոմ Եարճանեան), better known by his pen name Siamanto (Սիամանթօ) (15 August 1878 – August 1915), was an influential Armenian writer, poet and national figure from the late 19th century and early 20th century. He was killed by the Ottoman authorities during the Armenian Genocide.

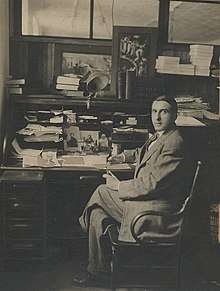

Siamanto | |

|---|---|

| Born | Atom Yarjanian 15 August 1878 Agn, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | August 1915 (aged 36–37) |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Nationality | Armenian |

| Education | University of Paris |

Life

He was born in 1878, in the town of Agn (Armenian: Ակն) on the shores of the river Euphrates. He lived in his native town until the age of 14. He studied at the Nersesian institute as a youth, where he developed an interest in poetry. The school’s director encouraged him to continue developing his poetic talents. The director, Garegin Srvandztiants, gave him the name Siamanto, after the hero of one of his stories. Atom would use this name for the rest of his days.[1]

Siamanto came from a middle-upper-class family. They moved to Constantinople (Istanbul) in 1891 where he continued his studies at the Berberian Institute. He graduated in 1896, during the bloody Hamidian massacres. Like many other Armenian intellectuals, he fled the country for fear of persecution. He ended up in Egypt where he became depressed because of the butchery that his fellow Armenians had to endure.[1]

In 1897, he moved to Paris and enrolled in literature at the prestigious Sorbonne University.[1] He was captivated by philosophy and Middle Eastern literature. He had to work various jobs while pursuing his studies because of his difficult financial situation. He developed many ties with well-known Armenian personalities in and outside Paris. He enjoyed reading in French and in Armenian, and read many of the best works of his time.

From Paris he moved to Geneva in Switzerland, and contributed to the newspaper Droshak, the organ of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation. His first poetic works were published in this newspaper under the headlines of Heroically (Armenian: Դիւցազնօրէն) and The Knight’s Song (Armenian: Ասպետին Երգը). The paper detailed the destruction of his homeland, was highly critical of the Ottoman government, and demanded equal rights for Armenians and more autonomy. Siamanto joined the cause and truly believed in an Armenia free of Turkish oppression.[2] Henceforth, many of his works and poems were highly nationalistic.

Siamanto fell ill in 1904, coming down with a case of pneumonia. He was treated at a hospital in Geneva and eventually fully recovered. For the next 4 years, he lived in various European cities such as Paris, Zurich, and Geneva. In 1908, along with many other Armenians, he returned to Constantinople after the proclamation of the Ottoman Constitution. However, in 1909, the Ottoman government made it clear that they were not safe by perpetrating the Adana massacre. Siamanto was once again deeply affected by the bloodshed. These events led him to write his famous Bloody News from my Friend (Armenian: Կարմիր լուրեր բարեկամէս).[2]

Works

Heroically (Armenian: Դիւցազնօրէն) was written starting in 1897 and finally printed in 1902 in Paris. It was a book about the hardships of Armenians living under the harsh Ottoman rule. Siamanto encouraged the youth to stand up for their rights and demand equality and justice.[1]

Sons of Armenia (Armenian: Հայորդիներ) was written between 1902 and 1908 and included three volumes. The first one was released in 1905 and dealt with the deep grief and mourning that many had to endure after the Hamidian massacres and other Turkish atrocities.[2]

Torches of Agony and Hope (Armenian: Հոգեվարքի եւ յոյսի ջահեր) was released in 1907 described in stunning details scenes of massacres, blood and anguish. He portrayed the deep thoughts and feelings of the victims and their daily torment. The plight of a whole people can be felt while reading this work. The author successfully makes the reader feel for the characters and easily win their sympathy.[2]

Bloody News from My Friend (Armenian: Կարմիր լուրեր բարեկամէս) was written right after the Adana massacre of 1909. It is a poetic work reflecting the pain the author felt for his fellow countrymen.[2]

The Homeland’s Invitation (Armenian: Հայրենի հրաւէր) was printed in 1910 and released in the United States. He wrote about his yearning for his country and encouraged Armenians living abroad to return to their native soil.[3]

Saint Mesrop (Armenian: Սուրբ Մեսրոպ), published in 1913, is a long poem dedicated to Saint Mesrop, the inventor of the Armenian alphabet.[3]

Writing style

Siamanto was a pioneer in Armenian poetry. His style was new and unique, and the methodology was exceptional. His themes were very dark and dealt extensively with death, torture, loss, misery, and sorrow. He recounted scenes of massacres, executions by hanging, bloody streets, pillaged villages, etc.; in other words, they dealt with the slaughter of Armenian men and women. The suffering of the people was continually tormenting him in turn.[2] He spent many sleepless nights thinking about those who perished. Writing about their fate was his way of coping with the pain and making sure they were not killed in silence. Life for the Armenians was bleak under Ottoman rule and Siamanto’s works described that fact of life very well.

However, his poems and writings go beyond the pain. He wrote about hope, freedom from oppression, and the possibility of a better future. His ideas also went to revolutionary themes and revenge for the murdered. Siamanto had two sides to his writing: one of lamentation, and the other of resistance.[2] It is from this ideology of resistance that his revolutionary beliefs grew. He was convinced that the road to salvation for his people was through armed struggle. He was hoping to ignite the revolutionary spirit in the younger generation of Armenians and to make them understand that indifference and inaction was not going to save them. He was so gripped with these troubles that he seldom wrote about himself, his personal life, love, or joy.

Siamanto had a very vivid imagination. The images he created can sometimes even feel a little out of the ordinary at times. He used many aspects from the symbolic school of thought in his works. He did not know modesty; we went to extremes both while writing about desperation or about hope. His consistency in his chosen themes went to show how passionately he felt for his cause. His works give a clear image of the spirit that existed at the time in the minds of many of the Armenian populace.

Death

In 1910, he moved to the United States as an editor at the Hairenik newspaper (Armenian: Հայրենիք). After a year, he returned to Constantinople. In 1913 he visited Tbilisi. On his way to his destination, he visited many famous Armenian landmarks such as Mount Ararat, Khor Virap and Echmiadzin.

He was one of the Armenian intellectuals tortured and killed by the Ottomans in 1915 during the Armenian Genocide.[3]

See also

- Armenian notables deported from the Ottoman capital in 1915

- Erukhan

- Krikor Zohrab

- Rupen Zartarian

References

- Hacikyan et al. 2005, p. 774.

- Hacikyan et al. 2005, p. 775.

- Hacikyan et al. 2005, p. 776.

- Hacikyan, Agop J.; Basmajian, Gabriel; Franchuk, Edward S.; Ouzounian, Nourhan (2005). The Heritage of Armenian Literature: From the Eighteenth Century to Modern Times. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-3221-8.

- Translated from Armenian: N.A. Արդի հայկական գրականութիւն, Գ հատոր, [Modern Armenian literature, Volume III], 2003, pp. 68–74

External links

| Armenian Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Siamanto. |