Shoshone Falls

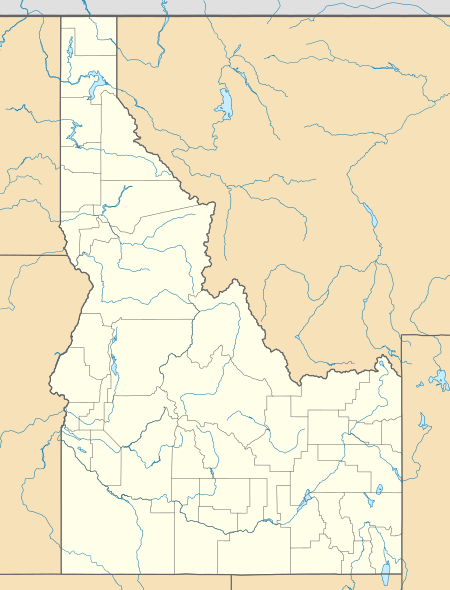

Shoshone Falls (/ʃoʊˈʃoʊn/) is a waterfall on the Snake River in southern Idaho, United States, approximately 3 miles (4.8 km) northeast of the city of Twin Falls. Sometimes called the "Niagara of the West," Shoshone Falls is 212 feet (65 m) high—45 feet (14 m) higher than Niagara Falls—and flows over a rim nearly 1,000 feet (300 m) wide.

| Shoshone Falls | |

|---|---|

Shoshone Falls in August 2018 | |

| |

| Location | Jerome/Twin Falls County, Idaho, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 42°35′43″N 114°24′03″W[1] |

| Type | Block |

| Elevation | 3,255 ft (992 m) at crest[1] |

| Total height | 212 ft (65 m)[2] |

| Number of drops | 1 |

| Total width | 925 ft (282 m)[2] |

| Watercourse | Snake River |

| Average flow rate | 3,530 cu ft/s (100 m3/s)[3] |

Formed by the cataclysmic outburst flooding of Lake Bonneville during the Pleistocene ice age about 14,000 years ago, Shoshone Falls marks the historical upper limit of fish migration (including salmon) in the Snake River, and was an important fishing and trading place for Native Americans. The falls were documented by Europeans as early as the 1840s; despite the isolated location, it became a tourist attraction starting in the 1860s. At the beginning of the 20th century, part of the Snake River was diverted for irrigation of the Magic Valley. Now, the flows over the falls can be viewed seasonally based on snowfall, irrigation needs and hydroelectric demands. Irrigation and hydroelectric power stations built on the falls were major contributors to the early economic development of southern Idaho.

The City of Twin Falls owns and operates a park overlooking the waterfall. Shoshone Falls is best viewed in the spring, as diversion of the Snake River can significantly diminish water levels in the late summer and fall. The flow over the falls ranges from more than 20,000 cubic feet per second (570 m3/s) during late spring of wet years, to a minimum "scenic flow" (dam release) of 300 cubic feet per second (8.5 m3/s) in dry years.

Characteristics

Shoshone Falls is in the Snake River Canyon on the border of Jerome and Twin Falls Counties, 615 miles (990 km) upstream from the Snake River's confluence with the Columbia River.[4] It is the tallest of several cataracts along this stretch of the Snake River, being located about 2 miles (3.2 km) downstream from Twin Falls and 1.5 miles (2.4 km) upstream from Pillar Falls. Directly above the Shoshone Falls, the Snake River narrows to less than 400 feet (120 m) wide and rushes over a series of rapids split by islands, before plunging over a vertical, horseshoe-shaped cliff 212 feet (65 m) high and 925 feet (282 m) wide.[2] The appearance of the falls varies significantly depending on the amount of water in the Snake River. During high water, the falls appear as a single block stretching the full width of the river. In low water, the falls split into four or more separate drops; the widest, northern section is also called Bridal Veil Falls.[5]

Flows

Located in an arid region, Shoshone Falls naturally received most of its water from snowmelt in the Rocky Mountains of Idaho and Wyoming near Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks, and to a lesser extent springs in the Snake River Canyon above Twin Falls. A large number of reservoirs, and massive diversions for the irrigation of nearly 2,000,000 acres (810,000 ha) of farmland,[6] have greatly reduced the volume of water reaching the falls, such that the canyon springs are now the primary water source. The average Snake River flow at the Twin Falls stream gaging station is 3,530 cubic feet per second (100 m3/s).[3] For comparison, the average Snake River flow at Idaho Falls – 190 miles (310 km) upstream – is 5,911 cubic feet per second (167.4 m3/s).[7] The average flow below Milner Dam, 24 miles (39 km) upstream, is just 884 cubic feet per second (25.0 m3/s), and is frequently zero in the late summer and fall.[8]

Idaho Power's Shoshone Falls Dam is located directly upstream from the falls and diverts water to the Shoshone hydroelectric plant, further reducing the water volume. Idaho Power is required to maintain a minimum daytime "scenic flow" of 300 cubic feet per second (8.5 m3/s) from April through Labor Day, although even this small flow can be difficult to achieve due to a lack of water in the Snake River.[9] Further complicating the issue is that most irrigation water is needed in the summer, which coincides with the peak tourist season.[10]:134 The Shoshone power plant draws up to 950 cubic feet (27 m3) of water per second; thus, the flow of the falls will only increase if the Snake River flow exceeds the combined plant capacity and scenic flow requirement. The best time to view the falls is between April and June, when snowmelt is peaking, and when water is released from upriver reservoirs to assist steelhead migration.[11]

The highest flow ever recorded at Twin Falls was 32,200 cubic feet per second (910 m3/s) on June 10, 1914, and the lowest was 303 cubic feet per second (8.6 m3/s) on April 1, 2013.[3] On a monthly basis, June generally sees the heaviest flows, at 6,280 cubic feet per second (178 m3/s), and August the lowest flows, 956 cubic feet per second (27.1 m3/s).[12]

Geology

Most of the rocks underlying the Snake River Plain originated from massive lava flows related to eruptions of the Yellowstone hotspot over many millions of years. Shoshone Falls flows over a 6-million-year-old rhyolite or trachyte lava flow that intersects the weaker basalt layers comprising the surrounding Snake River Plain, creating a natural knickpoint that resists water erosion.[13] The falls themselves were created quite suddenly during the cataclysmic Bonneville Flood at the end of the Pleistocene ice age about 14,500[14]–17,500[13] years ago, when pluvial Lake Bonneville, an immense freshwater lake that covered much of the Great Basin, overflowed through Red Rock Pass into the Snake River.[15][16] About 1,100 cubic miles (4,600 km3) of water were released[14]–1500 times the average annual flow of the Snake River at Twin Falls.[3] The massive flow of water carved the Snake River Canyon in a matter of several weeks, sculpting falls such as Shoshone Falls where the local geology intersected harder underlying rock layers.[14]

The immense Snake River Aquifer is formed in the region's porous volcanic rock and recharged each year by melting snow in the surrounding mountains. Because the Shoshone Falls canyon lies lower in elevation than the surrounding terrain, groundwater is forced to the surface via large springs in the canyon walls. Despite the almost total diversion of the river upstream from Milner Dam, these springs can provide up to 3,000 cubic feet per second (85 m3/s) of water to the falls. Spring flow varies widely depending on the season, although it has increased since the 1950s due to irrigation water on the surrounding plain percolating into the aquifer.[17][18]

Ecology

Due to its great height, Shoshone Falls is a total barrier to the upstream movement of fish. Anadromous fish (which live in the ocean as adults, but return to fresh water to lay eggs) such as salmon and steelhead/rainbow trout, and other migratory fish such as sturgeon, cannot pass the falls.[19]:607 Prior to the construction of many dams on the Snake River below Shoshone Falls, spawning fish would congregate in great numbers at the base of the falls, where they were a major food source for local Native Americans. Yellowstone cutthroat trout lived above the falls in the same ecological niche as rainbow trout below it, although their range has decreased since the 19th century due to river diversions and competition from introduced species such as lake trout. Due to this marked difference, the World Wide Fund for Nature uses Shoshone Falls as the boundary between the Upper Snake and the Columbia Unglaciated freshwater ecoregions. The Snake River above Shoshone Falls shares only 35 percent of its fish species with those of the lower Snake River below the falls.[20][21] Fourteen fish species found in the upper Snake are also found in the Bonneville freshwater ecoregion (which covers the Great Basin portion of Utah), but not the lower Snake or Columbia rivers. The upper Snake River is also high in freshwater mollusk endemism (such as snails and clams).[22]

History

Native peoples and explorers

The Shoshone Falls are named for the Lemhi Shoshone or Agaidika ("Salmon eaters") people, who depended on the Snake River's immense salmon runs as their primary food source, though they also supplemented their diet with various roots, nuts and large game such as buffalo.[23]:257 Because the falls are the upstream limit of salmon migration in the Snake River, they served as a central food source and trading center for the native peoples, who fished with willow spears tipped with elk horn.[24]:39 The Bannock people also traveled to Shoshone Falls each summer to gather salmon.[25]:113

Although the Lewis and Clark Expedition encountered the Shoshone Indians in 1805-06 they did not pass through the Shoshone Falls area. The 1811 Wilson Price Hunt Expedition, whose goal was to scout routes for the growing fur trade, traveled down the Snake River as far as Caldron Linn, a wild rapids located near present-day Murtaugh, Idaho. There, where the river drops into the precipitous Snake River Canyon, a canoe capsized and one of Hunt’s Canadian boatmen was drowned. Although the party explored the canyon for several miles downstream, Hunt’s journal does not mention any waterfalls as large as Shoshone Falls. Hunt then split the group to make foraging easier and they basically walked out of Idaho.[26] The routes they pioneered would become part of the Oregon Trail, which would later bring many emigrants from the eastern United States to the Shoshone Falls area.[27]

Over the next thirty years, American and British-Canadian fur trappers hunted throughout south-central Idaho and are believed to have observed Shoshone Falls. However, none of those who kept journals mentioned the feature.[28]

John C. Frémont passed through the Shoshone Falls area during his 1843 expedition, which aimed to map the country through which passed the western half of the Oregon Trail.[29] None of his party observed the falls, however, because they left the river canyon (probably near Murtaugh) and cut southwest across a sandy plain to reach Rock Creek.[30] They returned to the canyon rim where Rock Creek enters the Snake. There, he observed the Thousands Springs, which he described as “a subterranean river [that] bursts out directly from the face of the escarpment.”

They descended into the canyon with some difficulty, made some river measurements, and continued downstream. They camped about a mile below what Frémont called "Fishing Falls": "a series of cataracts with very inclined planes, which are probably so named because they form a barrier to the ascent of the salmon; and the great fisheries from which the inhabitants of this barren region almost entirely derive a subsistence commence at this place."[31] He observed that the salmon were "so abundant that they [the Shoshone] merely throw in their spears at random, certain of bringing out fish."[31] This stretch of the river is now known as Salmon Falls.[32]:121[33] Early encounters between Europeans and Native Americans were generally friendly, but eventually brutal conflicts broke out over land ownership. After the Snake War, some twenty years later, the Shoshone were confined on reservations elsewhere.[23]:257

Pioneer traffic along the Oregon Trail through Idaho increased steadily from 1843 on, with a spurt after Frémont’s journal was published and distributed. In 1847, some 4,000 emigrants passed through on their way to Oregon.[34] One of the parties that year included Roman Catholic Bishop Augustin-Magloire Blanchet, who had been appointed to lead the new Diocese of Walla Walla. Traveling along the north side of the river, the group made a detour, perhaps guided by a former trapper who was familiar with the area. Blanchett then made the first known written record of seeing Shoshone Falls. Being from Quebec, Canada, he called the feature “Canadian Falls.”[35][30]

That designation did not last very long, however. In August, 1849, a column of U. S. Army “Mounted Rifles” marched by, headed for Oregon. They took a route somewhat closer to the canyon and could actually hear the thunder of the falls. A local Indian had told their guide about the feature, so the guide led Lieutenant Andrew Lindsay and George Gibbs, a civilian writer and artist, to see them. Gibbs drew the first known image of the falls, and the pair selected “Shoshone Falls” as a more appropriate name.[36]

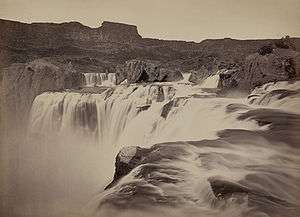

The 1868 Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel, led by later U.S. Geological Survey director Clarence King, was the first to closely study the geology, soils and minerals of the Shoshone Falls area. King described the country as "strange and savage", and said of the falls themselves: "You ride upon a waste. Suddenly, you stand upon a brink. Black walls flank the abyss. A great river fights its way through the labyrinth of blackened ruins and plunges in foaming whiteness."[37] He was also the first to speculate that the falls and canyon, rather than being formed by erosion over millennia, might have been created by "moments of great catastrophe" considering the region's chaotic volcanic history.[37] Timothy H. O'Sullivan was also a member of the 1868 expedition, and became the first national photographer to picture the falls.[38] O'Sullivan also returned to the area in 1874, again to photograph Shoshone Falls.[39][40]

Tourism and development

The Shoshone Falls first became a tourist attraction in the mid-19th century, despite its inhospitable and isolated surroundings. Travelers on the Oregon Trail often stopped to visit the falls, which required only a "slight detour" to the north.[41] Promoters of tourism to the falls cited the "lonely grandeur" of the surrounding country and the fact that the falls were not "overshadowed by a city",[42] perhaps in reference to Niagara Falls which at this time had become infamous for the rampant commercial development adjacent to it. The first known reference to Shoshone Falls as "The Niagara of the West" was in an article from an unknown Salt Lake City paper, reprinted in the Philadelphia Bulletin in 1866, in which the falls were described as "a world wonder which for savage scenery and power sublime stands unrivaled in America".[43] The falls were painted by Thomas Moran, famous for his depictions of rugged Western landscapes such as Yellowstone, in 1900 for the 1901 Pan-American Exposition.[44]

In 1869 gold was discovered in the Snake River Canyon in the vicinity of Shoshone Falls, and by 1872 about 3,000 miners had come to the area in search of the precious metal.[45] The richest deposits were said to be in the area between Murtaugh, about 15 miles (24 km) above Shoshone Falls, and Clark's Ferry, about 20 miles (32 km) below the falls. The towns of Shoshone City, Springtown and Drytown were created as a result of the gold rush. However, the boom quickly ended as the local geology and manner of sediment deposits made it difficult to remove gold. The first miners were mainly of European descent, and were later replaced by Chinese miners who continued to work the claims into the early 1880s, in search of the fine gold particles known as "gold flour".[46]

In 1876, Charles Walgamott, a local homesteader, foresaw the potential of the falls as a tourist destination, fenced large tracts of land surrounding the falls and began construction on a lodge, hoping to obtain title to said land through squatter's rights.[47] In 1883 the Oregon Short Line Railroad was extended to Shoshone, Idaho, making travel to the falls much easier, and Walgamott sold the land to "a syndicate of capitalists including Montana Senator William A. Clark, who intended to replace the hotel with a far grander establishment and to place a recreational steamship on the river."[48] In April of the following year Walgamott was granted a license to operate a cable ferry across the Snake River upstream of the falls. Not surprisingly, this ferry was one of the most dangerous river crossings in Idaho. In 1904 and 1905 boats broke loose from the cable and were swept over the falls, killing four people. Many other near misses and incidents also took place.[47] The hazards of the crossing led to a demand for a road or rail bridge that would span the canyon just below the falls. Although Twin Falls County commissioners deemed the idea "feasible", it was ultimately dropped due to its high cost.[49] In 1919, the Hansen suspension bridge was built across a narrower part of the Snake River Canyon about 6 miles (9.7 km) upstream.[50]

Irrigation and the drying of Shoshone Falls

Ira Burton Perrine arrived in the Shoshone Falls area in 1884 and initially homesteaded at the bottom of the Snake River Canyon, where he raised cattle and planted orchards. He later became involved in the tourist business, starting a ferry and a stagecoach service, and building the Blue Lakes Hotel.[51]:23 However, Perrine is best known for his role in the economic development of southern Idaho based on massive irrigation projects, and consequentially, the periodic drying of Shoshone Falls. In 1900 the Twin Falls Land and Water Company was incorporated and filed claim for 3,000 cubic feet per second (85 m3/s) of water from the Snake River. Perrine's ultimate goal was to irrigate 500,000 acres (200,000 ha) of land. Although this would have been impermissible in other parts of the western US, due to regulations such as those under the Homestead Act which limited each settler's claim to 160 acres (65 ha), Perrine's project fell under the boundaries of the 1894 Carey Act, which allowed private companies to construct large-scale irrigation systems in desert regions where the task would be far too great for individual settlers.[52]

Perrine proposed the diversion of the Snake River at Caldron Linn, a point approximately 24 miles (39 km) upstream of Shoshone Falls. Senator Clark and others who owned land at Shoshone Falls filed a lawsuit against the Twin Falls Land and Water Company, but were defeated in the Idaho Supreme Court in 1904.[53] The Milner Dam and the major canals required to deliver water were completed by 1905. "On March 1, 1905, Frank Buhl gave a ceremonial pull on the wheel on a winch and the gates of Milner Dam were closed, and the gates to a thousand miles of canal and laterals were opened, and the Snake River was diverted, and that night Shoshone Falls went dry as the water rushed across the desert far above, and Perrine's vision was realized, and 262,000 acres of desert were shortly transformed."[54]

The reclamation of vast tracts of desert into productive farmland practically overnight led to the regional moniker of "Magic Valley". Powered entirely by gravity, it was "a rare successful example" of private irrigation development under the Carey Act.[55] The city of Twin Falls was incorporated in 1905, on lands originally platted for town development as part of the irrigation project. In 1913, Perrine built an electric streetcar system to transport tourists from Twin Falls to the Shoshone Falls. In part due to the intervention of World War I which resulted in short supply of iron, the rail line was never completed as planned. The post-war rise in automobile ownership also made the line obsolete, and it was de-commissioned in 1916.[56]

The Shoshone Falls Power Plant was completed in 1907 by the Greater Shoshone and Twin Falls Water Power Company. A low head diversion dam (the Shoshone Falls Dam) was built directly upstream of the falls and diverted water into a penstock, further reducing the amount of water flowing over the falls. The plant initially had a capacity of 500 kilowatts (KW).[57] The plant was purchased by Idaho Power in 1916. Over the years the power plant was expanded and ultimately replaced with newer units capable of generating 12,500 KW.[58] Currently about 950 cubic feet per second (27 m3/s) are required to run the plant at full capacity. In 2015 Idaho Power released a plan to increase the capacity to 64,000 KW, which would increase the water diversions and consequently effect even greater reductions of the water available to flow over the falls.[59]

Evel Knievel's jump

On September 8, 1974, American daredevil Evel Knievel attempted to jump over the Snake River approximately 1 mile (1.6 km) west of the falls on a rocket-powered motorcycle, the Skycycle X-2, after unsuccessfully petitioning the U.S. Government to let him attempt a jump over the Grand Canyon. Knievel and his team purchased land on both sides of the Snake River and built a large earthen ramp and launch structure. A crowd of 30,000 gathered to watch Knievel's jump,[60]:595 which failed because his parachute opened too early, causing him to float down towards the river. Knievel likely would have drowned were it not for canyon winds that blew him to the river bank; he ultimately survived with a broken nose.[61][62] In September 2016, professional stuntman Eddie Braun successfully jumped the Snake River Canyon in a replica of Knievel's rocket.[63]

Public access and recreation

.jpg)

As early as 1900, locals called for the creation of a national park at Shoshone Falls, although this proposal was never approved by Congress. In 1919 the Shoshone Falls Memorial Park Association proposed a memorial park at the falls for World War I veterans. The association hired California landscape architect Florence Yoch to design a plan for the park.[64] However, these plans never materialized, in part due to the difficulties of obtaining the needed land from its previous owners. Frederick and Martha Adams later bought the land from Senator Clark, and donated it to the City of Twin Falls in 1932. The state of Idaho donated another tract of land in 1933 to add to the park.[65]

Today, Shoshone Falls Park encompasses the south bank of the Snake River at the falls. A $5 vehicle fee is posted from March 30 through September 30th .[66] The park includes an overlook, interpretive displays and a trail system along the south rim of the Snake River Canyon. The trails provide access to nearby points of interest including Dierkes Lake and Evel Knievel's 1974 jump site. About 250,000 to 300,000 vehicles enter the park each year.[67]

In 2015 Idaho Power completed the Shoshone Falls Expansion Project, which involved reconstructing portions of the Shoshone Falls Dam to reduce its aesthetic impact on the area, and to direct low water releases to the most scenic part of the falls, the "Bridal Veil Falls" on the north bank of the river.[68][69]

References

- "Shoshone Falls". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. 1979-06-21. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- "Shoshone Falls". Northwest Waterfall Survey. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- "USGS Gage #13090500 on the Snake River near Twin Falls, ID" (PDF). National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1911–2013. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- USGS Topo Maps for United States (Map). Cartography by United States Geological Survey. ACME Mapper. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- "Shoshone Falls Improvement Project". Idaho Power. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- "USGS #13087995 Snake River Gaging Station near Milner, ID" (PDF). National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1992–2013. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- "USGS Gage #13057155 on the Snake River above Eagle Rock near Idaho Falls, ID" (PDF). National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1992–2013. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- "USGS #13087995 Snake River Gaging Station near Milner, ID: Monthly Statistics". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1992–2013. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- Dunlap, Tetona (2016-04-01). "Low Water Means Small Shoshone Falls Flows". MagicValley.com. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (1990). Snake River Mainstem Hydroelectric Projects, Twin Falls (no.18), Milner (no.2899), Auger Falls (no.4797), Star Falls (no.5797): Environmental Impact Statement. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Weeks, Andrew (2016-04-11). "Water Released in May to Increase Flows at Shoshone Falls". Fox News. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- "USGS Gage #13090500 on the Snake River near Twin Falls, ID: Monthly Statistics". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1911–2013. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- Bonnichsen, Bill. "Secrets of the Snake River Plain Revealed". Idaho Public Television. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- DeGrey, Laura; Miller, Myles; Link, Paul. "Lake Bonneville Flood". Digital Geology of Idaho. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- "Shoshone Falls on the Snake River, Idaho" (PDF). Amherst College. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- Link, Paul K.; Kaufman, Darrell S.; Thackray, Glenn D. "Field Guide to Pleistocene Lakes Thatcher and Bonneville and the Bonneville Flood, Southeastern Idaho" (PDF). Idaho State University. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- "Shoshone Falls Has Attracted Sightseers For 150 Years". American Tradition Almanac. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- Kjelstrom, L.C. (1995). "Methods to Estimate Annual Mean Spring Discharge to the Snake River Between Milner Dam and King Hill, Idaho" (PDF). USGS Water-Resources Investigation Report 95-4055. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- Benke, Arthur C.; Cushing, Colbert E., eds. (2011). Rivers of North America. Academic Press. ISBN 0-08045-418-6.

- "122: Upper Snake". Freshwater Ecoregions of the World. World Wide Fund for Nature/The Nature Conservancy. 2015-10-02. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- "Ecoregions of Idaho" (PDF). U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- Abell, Robin A., David M. Olson, Eric Dinerstein, Patrick T. Hurley et al. (WWF) (2000). Freshwater Ecoregions of North America: a conservation assessment. Island Press. ISBN 1-55963-734-X.

- Buckley, Jay H.; Nokes, Jeffery D. (2016). Explorers of the American West: Mapping the World through Primary Documents. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-61069-732-4.

- Dary, David (2007). The Oregon Trail: An American Saga. Knopf Doubleday. ISBN 0-30742-911-3.

- Luebering, J.E. (2010). Native American History. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 1-61530-130-5.

- Hunt, Wilson Price; Franchère, Hoyt C., editor and translator (1973). Overland Diary of Wilson Price Hunt, translated from the original French Nouvelles Annales des Voyages (Paris, 1821). Oregon Book Society.

- Lohse, E.S. (1993). "Southeastern Idaho Native American Prehistory and History". Idaho Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- Beal, Merrill D.; Wells, Merle W. (1959). History of Idaho, Lewis Historical Publishing Company, Inc.

- Fremont, John C. Frémont (1845). Report of the Exploring Expedition to the Rocky Mountains ... The Senate Of The United States, Government Printing Office.

- Gentry, Jim (2003). In the Middle and On the Edge: The Twin Falls Region of Idaho, College of Southern Idaho. ISBN 0974763306.

- "Who's Who - Northern Shoshone and Bannock". Trail Tribes. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- Stuart, Robert (1935). Rollins, Philip Ashton (ed.). The Discovery of the Oregon Trail: Robert Stuart's Narratives of His Overland Trip Eastward from Astoria in 1812-13. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-80329-234-1.

- "Idaho State Historical Society Reference Series: Salmon Falls and Thousand Springs" (PDF). Idaho State Historical Society. 1987. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- Unruh, John D., Jr. (1929). The Plains Across: The Overland Emigrants and the Trans-Mississippi West, 1840-1860. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0252063600.

- Blanchet, Augustine Magloire Alexander (1978). Journal of a Catholic Bishop on the Oregon Trail, Ye Galleon Press.

- Settle, Raymond W., editor (1989). The March of the Mounted Riflemen. University of Nebraska Press.

- Shallat, Todd. "Todd Shallat's Terra Idaho history column: In 1868, a U.S. geography team encountered the magic of the Snake River Basin". Idaho Statesman. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- Frank H. Goodyear III (2011). An Early Photograph of Shoshone Falls: Uncovering a Network of Communities in 1870s Idaho, History of Photography, 35:3, 269-280. Note: At least two photographers, Salt Lake City photographer Charles Roscoe Savage in December 1867, June 1868, and July 1874, and Silver City, Idaho, photographer John Junk in June 1868 took pictures of Shoshone Falls prior to Timothy H. O'Sullivan, who as photographer of the US Army Corps of Engineers took pictures in September–October 1868 and November 1874. Also, there are at least two unattributed early photographs of Shoshone Falls suggesting that there might have been other pioneer photographers.

- "Historical Perspective: Timothy O'Sullivan". Photo District News. 2011-11-07. Retrieved 2016-05-27.

- "Shoshone Canyon and Falls, 1868". Archives of the West. Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- Moreno, Rich (2013-09-27). "Shoshone Falls: Tamed but never conquered". Nevada Appeal. Retrieved 2017-01-11.

- Schwantes, Carlos A. (1993). "Tourists in Wonderland: Early Railroad Tourism in the Pacific Northwest" (PDF). Washington State Historical Society. Retrieved 2017-01-11.

- "Moran: 1900-1926". National Gallery of Art. Retrieved 2017-01-11.

- Anderson, Nancy K. (1997). Thomas Moran. Yale University Press. p. 162. ISBN 0-30007-325-9.

- "The Twin Falls (no.18), Milner (no.2899), Auger Falls (no.4797), and Star Falls (no.5797) Hydroelectric Projects on the Main Stem of the Snake River, Idaho: Draft Environmental Impact Statement". Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. Nov 1987.

- Matthews, Mychel (2012-09-20). "Mining on the Banks of the Snake River". Magicvalley.com. Retrieved 2017-01-11.

- Hart, Arthur (2015-04-05). "Idaho History: Shoshone Falls was spectacular – and sometimes deadly". Idaho Statesman.

- Goodyear, Frank H. (Aug 2011). "An Early Photograph of Shoshone Falls: Uncovering a Network of Communities in 1870s Idaho" (PDF). Smithsonian Libraries. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- Matthews, Mychel (2014-12-04). "Hidden History: The Shoshone Falls Bridge". MagicValley.com. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- Matthews, Mychel (2015-11-10). "Hidden History: The 1st Hansen Bridge". MagicValley.com. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- Giraud, Elizabeth Egleston (2010). Twin Falls. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-73858-027-9.

- "Ira Burton Perrine". Idaho Museum of Natural History. Idaho State University. Retrieved 2016-06-27.

- "Shoshone Falls Has Attracted Sightseers For 150 Years". American Tradition Almanac. 2014-06-15. Retrieved 2016-06-27.

- Yost, Joe. "History of Milner Dam". Twin Falls Canal Company. Archived from the original on 2001-04-08. Retrieved 2016-06-27.

- "Milner Dam and the Twin Falls Main Canal" (PDF). Idaho State Historical Society. 1986-06-11. Retrieved 2017-05-17.

- Matthews, Mychel (2016-03-31). "Hidden History: Perrine's Electric Railroad to Shoshone Falls". MagicValley.com. Retrieved 2017-05-17.

- Matthews, Mychel (2012-12-20). "Hidden History: The Power Plant at Shoshone Falls". MagicValley.com. Retrieved 2017-05-17.

- "Shoshone Falls Project". Idaho Power. Retrieved 2017-05-17.

- Poppino, Nate (2010-03-14). "The future of the falls Power-plant turbine upgrade could alter views of Shoshone Falls". MagicValley.com.

- Let's Go Inc. (2005). Roadtripping USA: The Complete Coast-to-Coast Guide to America. Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-33569-5.

- "Evel Knievel's Snake River Jump Monument". RoadsideAmerica.com. Retrieved 2016-06-09.

- "Evel Knievel's Motorcycle Jump". College of Southern Idaho. Retrieved 2016-06-09.

- "Daredevil successfully powers rocket over Snake River Canyon". Associated Press. 2016-09-17. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- Matthews, Mychel (2013-06-06). "Hidden History - Shoshone Falls: An Unfulfilled Memorial". MagicValley.com. Retrieved 2016-06-04.

- "Shoshone Falls". College of Southern Idaho. Retrieved 2016-06-04.

- "Shoshone Falls". Visit Idaho. Retrieved 2016-06-04.

- Wooton, Julie (2011-04-29). "Daytrip option: Shoshone Falls". Elko Daily Free Press. Retrieved 2016-06-04.

- "Shoshone Falls Expansion Project" (PDF). Idaho Power. Retrieved 2016-06-04.

- "What Is that Construction at Shoshone Falls?". MagicValley.com. 2015-04-15. Retrieved 2016-06-04.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shoshone Falls. |

- Current water flow over Shoshone Falls – City of Twin Falls