Shell Crisis of 1915

The Shell Crisis of 1915 was a shortage of artillery shells on the front lines in the First World War that led to a political crisis in the United Kingdom. The military historian Hew Strachan wrote that military strategy led an over-reliance on shrapnel to attack infantry in the open, which was negated by the resort to trench warfare, for which high-explosive shells were better suited.[1] At the start of the war there was a revolution in doctrine: instead of the idea that artillery was a useful support for infantry attacks, the new doctrine held that heavy guns alone would control the battlefield. Because of the stable lines on the Western Front, it was easy to build railway lines that delivered all the shells the factories could produce. The "shell scandal" emerged in 1915 because the high rate of fire over a long period was not anticipated and the stock of shells became depleted.[2]

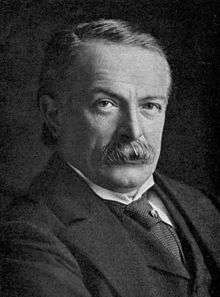

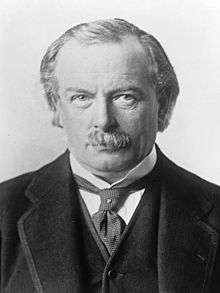

The shortage was widely publicized in the press. The Times, in cooperation with David Lloyd George and Lord Northcliffe, sought to force Parliament to adopt a national munitions policy with centralised control. The result was a coalition government with Lloyd George as Minister of Munitions. In 1916 the long-term effects included the fall of the Prime Minister H. H. Asquith and his replacement by Lloyd George in December 1916.[3]

The Times attacks Kitchener

Shortage of ammunition had been a serious problem since the autumn of 1914 and the British Commander-in-Chief Field Marshal Sir John French gave an interview to The Times (27 March) calling for more ammunition. Lord Northcliffe, the owner of The Times and the Daily Mail, blamed Herbert Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War, for the recent death in action of his nephew.[4] On the basis of an assurance from Kitchener, Asquith, stated in a speech at Newcastle (20 April) that the army had sufficient ammunition.[5]

After the failure of the Battle of Aubers Ridge on 9 May 1915, The Times war correspondent, Colonel Charles à Court Repington, sent a telegram to his newspaper blaming lack of high-explosive shells. French had, despite Repington’s denial of his prior knowledge at the time, supplied him with information and sent Brinsley Fitzgerald and Freddy Guest to London to show the same documents to Lloyd George and senior Conservatives Bonar Law and Arthur Balfour.[5]

The Times headline on 14 May 1915, was: "Need for shells: British attacks checked: Limited supply the cause: A Lesson From France".[6] It commented "We had not sufficient high explosives to lower the enemy's parapets to the ground ... The want of an unlimited supply of high explosives was a fatal bar to our success", blaming the government for the battle's failure.[7]

Coalition Government

The visit of the opposition leaders to Asquith on 17 May was caused more by the resignation of John Fisher as First Sea Lord on 15 May than by the Shells Scandal. As a result of the meeting Asquith wrote to his ministers demanding their resignations.[8] Asquith formed a new coalition government and appointed Lloyd George as Minister of Munitions. Although Liberal politicians held office in subsequent coalitions, no purely Liberal government has held office since May 1915.

Daily Mail attacks Kitchener

A sensational version of the story was printed in the popular Daily Mail on 21 May, blaming Kitchener, under the headline "The Shells Scandal: Lord Kitchener’s Tragic Blunder". Lloyd George had to warn Northcliffe that the campaign was counterproductive and creating sympathy for Kitchener.[9] Kitchener wanted to let the Shells Scandal drop. Von Donop, Master-General of the Ordnance, demanded an Inquiry to clear his name but Kitchener persuaded him to withdraw the request as it would have led to French’s dismissal.[10] Kitchener remained in office as Secretary of State for War, responsible for training and equipping the volunteer New Armies but lost control over munitions production and was increasingly sidelined from control of military strategy. French was also tarnished by his blatant meddling in politics, a factor which contributed to his enforced resignation in December 1915.

Ministry of Munitions

The Munitions of War Act 1915 ended the shell crisis and guaranteed a supply of munitions that the Germans were unable to match. The government policy, according to J. A. R. Marriott, was that,

No private interest was to be permitted to obstruct the service, or imperil the safety, of the State. Trade Union regulations must be suspended; employers' profits must be limited, skilled men must fight, if not in the trenches, in the factories; man-power must be economized by the dilution of labour and the employment of women; private factories must pass under the control of the State, and new national factories be set up. Results justified the new policy: the output was prodigious; the goods were at last delivered.[11]

Following the creation of the Ministry of Munitions, new factories began to be built for the mass production of war material. The construction of these factories took time and to ensure that there was no delay in the production of munitions to deal with the Shell Crisis, the Government turned to railway companies to manufacture materials of war. Railway companies were well placed to manufacture munitions and other war materials, with their large locomotive, carriage works and skilled labourers; by the end of 1915 the railway companies were producing between 1,000 and 5,000 6-inch. H.E. shells per week.[12]

As well as the components for a number of different types of shell, the Railway companies, under the direction of the Railway War Manufactures Sub-Committee of the Railway Executive Committee, produced mountings for larger artillery, water-tank carts, miners' trucks, heavy-capacity wagons, machinery for howitzer carriages, armoured trains and ambulances. In 1916, when the many factories being constructed by the Ministry of Munitions began producing large volumes of munitions, the work of the Railway Companies in producing war materials actually increased and they continued to produce high volumes of munitions throughout the war. The official record, presented to the Government in May 1920, of the munitions work done throughout the war by the various railway companies ran to a total of 121 pages, giving some idea of the scale of what was undertaken by the Railway Companies across the country. Many of the companies undertook this vital war work to the detriment of the maintenance of their locomotives, carriages and wagons.[12]

The Munitions of War Act 1915 prevented the resignation of munitions workers without their employer's consent. It was a recognition that the whole economy would have to be mobilised for the war effort if the Allies were to prevail on the Western Front. Supplies and factories in British Commonwealth countries, particularly Canada, were reorganised under the Imperial Munitions Board, to supply adequate shells and other materiel for the remainder of the war. The Health of Munitions Workers Committee, one of the first investigations into occupational safety and health, was set up in 1915 to improve productivity in factories.[13] [14] A huge munitions factory, HM Factory, Gretna was built on the English-Scottish border to produce Cordite. There were at least three major explosions in such factories:

- An explosion at Faversham involving 200 tons of TNT killed 105 in 1916.

- The National Shell Filling Factory, Chilwell exploded in 1918, killing 137.

- The Silvertown explosion occurred in Silvertown (now part of the London Borough of Newham, in Greater London) killing 73 and injuring 400 on Friday, 19 January 1917 at 6.52 pm.

See also

- Munitionettes

- National Filling Factory, Georgetown (NFF No 4, in Scotland)

Footnotes

- Strachan 2001, pp. 992–1,105.

- French 1979, pp. 192–205.

- Fraser 1983, pp. 77–94.

- Holmes 2004, pp. 289–290.

- Holmes (2004), p. 287.

- Holmes (2004), pp. 287–289.

- Duffy 2009.

- Holmes 2004, p. 288.

- Holmes 2004, pp. 288–289.

- Holmes 2004, p. 291.

- Marriott 1948, p. 376.

- Pratt 1921, p. 7.

- Weindling 1985, p. 91.

- BLS 1916, pp. 66–70.

References

- Duffy, Michael (2009). "The Shell Scandal, 1915". FirstWorldWar.com. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- Fraser, Peter (April 1983). "The British 'Shells Scandal' of 1915". Canadian Journal of History. 18 (1): 69–86. doi:10.3138/cjh.18.1.69.

- French, David (September 1979). "The Military Background to the 'Shell Crisis' of May 1915". Journal of Strategic Studies. II (2): 192–205. doi:10.1080/01402397908437021.

- "Health of Munitions Workers, Great Britain". Monthly Review of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. II (5): 66–70. May 1916. JSTOR 41822985.

- Holmes, Richard (2004). The Little Field Marshal: A Life of Sir John French. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-84614-7.

- Marriott, J. A. R. (1948). Modern England: 1885–1945 (4th ed.). London: Methuen. OCLC 407888.

- Pratt, Edwin A. (1921). British Railways and the Great War Book. London: Selwyn and Blount. ISBN 978-1-1518-5240-3.

- Strachan, Hew (2001). The First World War: To Arms. I. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1916-0834-6.

- Weindling, Paul (1985). The Social History of Occupational Health. Croom Helm: Society for the Social History of Medicine. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-7099-3606-0.

Further reading

- Adams, R. J. Q. (1978). Arms and the Wizard: Lloyd George and the Ministry of Munitions 1915–1916. London: Cassell. ISBN 0-304-29916-2.

- Brown, I. M. (1996). The Evolution of the British Army's Logistical and Administrative Infrastructure and its Influence on GHQ's Operational and Strategic Decision-Making on the Western Front, 1914–1918 (PhD). London: London University. OCLC 53609664. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- Carnegie, David (1925). The History of Munitions Supply in Canada 1914–1918. London: Longmans Green and Co. OCLC 224844256.

- Lloyd George, David (1933). War Memoirs of David Lloyd George. London: Ivor Nicholson & Watson. OCLC 1140996940.