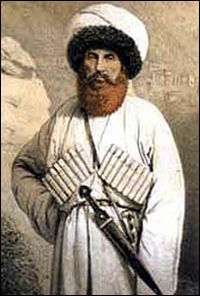

Shamil, 3rd Imam of Dagestan

Imam Shamil (English: also spelled Shamyl, Schamil, Schamyl or Shameel; Avar: Шейх Шамил; Turkish: Şeyh Şamil; Russian: Имам Шамиль; Arabic: الشيخ شامل) (pronounced "Shaamil") (26 June 1797 – 4 February 1871) was the political, military, and spiritual leader of Caucasian resistance to Imperial Russia in the 1800s,[1]the third Imam of the Caucasian Imamate (1840–1859), and a Shaykh of the Naqshbandi Sufi Tariqa.[2]

| Imam Shamil | |

|---|---|

| |

| Imam of the Dagestan | |

| Reign | 1834 - 1859 |

| Predecessor | Gamzat-bek |

| Successor | Overthrown by the Russian Empire |

| Born | 26 June 1797 Gimry, Dagestan |

| Died | 4 February 1871 (aged 73) Medina, Hejaz, Ottoman Empire |

| Burial | |

| Father | Dengau |

| Religion | Sunni Islam (Naqshbandi Sufism) |

Family and early life

Imam Shamil was born in 1797, to an Avar Muslim family of Kumyk descent,[3][4][5][6] in the small village (aul) of Gimry, which is in present-day Dagestan, Russia. He was originally named Ali, but following local tradition, his name was changed when he became ill. His father, Dengau, was a landlord, and this position allowed Shamil and his close friend Ghazi Mollah to study many subjects including Arabic and logic. There are contemporary to Shamil source, where he called himself "Tatar".[7] Tatars (Dagestanian Tatars) used to be one of Russian administration's name for Kumyks.[8]

Shamil was born at a time when the Russian Empire was expanding into the territories of the Ottoman Empire and Persia (see Russo-Persian War (1804-1813) and Russo-Turkish War (1806–1812)). Many Caucasian nations united in resistance to Russian imperial aspirations in what became known as the Caucasian War. Some of the earlier leaders of Caucasian resistance were Sheikh Mansur and Ghazi Mollah. Shamil was actually childhood friends with the Mollah, and would become his disciple and counsellor.

Shamil had multiple wives including one of Russian and Armenian heritage named Anna Ivanovna Ulykhanova (1828-1877).[9][10] She converted to Islam as a teenager and adopted the name "Shuanet," remaining loyal to Shamil even after his capture and exile to Russia.[9] After Shamil's death in 1871, she moved to the Ottoman Empire where she was assigned a pension from the sultan.[9]

War against Russia

In 1832, Ghazi Mollah died at the battle of Gimry, and Shamil was one of only two Murids to escape, but he sustained severe wounds. During this fight he was stabbed with a bayonet. After jumping from an elevated stoop "clean over the heads of the very line of soldiers about to fire on him. Landing behind them, whirling his sword in his left hand he cut down three of them, but was bayoneted by the fourth, the steel plunging deep in his chest. He seized the bayonet, pulled it out of his own flesh, cut down the man, and with another superhuman leap, cleared the wall and vanished in the darkness".[11] He went into hiding and both Russia and Murids assumed him dead. Once recovered, he emerged from hiding and rejoined the Murids, led by the second Imam, Gamzat-bek. He would wage unremitting warfare on the Russians for the next quarter century and become one of the legendary guerrilla commanders of the century. When Gamzat-bek was murdered by Hadji Murad in 1834, Shamil took his place as the prime leader of the Caucasian resistance and the third Imam of the Caucasian Imamate.[12][13]

In 1839 (June–August), Shamil and his followers, numbering about 4000 men, women and children, found themselves under siege in their mountain stronghold of Akhoulgo, nestled in the bend of the Andi Koysu, about ten miles east of Gimry. Under the command of General Pavel Grabbe, the Russian army trekked through lands devoid of supplies because of Shamil's scorched-earth strategy. The geography of the stronghold protected it from three sides, adding to the difficulty of conducting the siege. Eventually the two sides agreed to negotiate. Complying with Grabbe's demands, Shamil gave his son, Jamaldin in a sign of good faith, as a hostage. Shamil rejected Grabbe's proposal that Shamil command his forces to surrender and for him to accept exile from the region. The Russian army attacked the stronghold, after 2 days of fighting, the Russian troops had secured it. Shamil escaped the siege during the first night of the attack. Shamil's forces had been broken and many Dagestani and Chechen chieftains proclaimed loyalty to the Tsar. Shamil fled Dagestan for Chechnya. There he made quick work of extending his influence over the clans.[14]

Shamil was effective at uniting the many, quarrelsome Caucasian tribes to fight against the Russians, by the force of his charisma, piety and fairness in applying Sharia law. One Russian source commented on him as "a man of great tact and a subtle politician." He believed the Russian introduction of alcohol in the area corrupted traditional values. Against the large regular Russian military, Shamil made effective use of irregular and guerrilla tactics. In 1845 an 8-10,000 strong column under the command of Count Michael Vorontsov followed the Imamate's forces into the forests of Chechnya. The Imamte's forces surround the Russian column, destroying it.[15]

His fortunes as a military leader rose after he was joined by Hadji Murad, who defected from the Russians in 1841 and tripled by his fighting the area under Shamil's control within a short time. Hadji Murad, who was to become the subject of a famous novella by Leo Tolstoy (1904), turned against Shamil a decade later, apparently disappointed by his failure to be anointed Shamil's successor as imam. Shamil's elder son was given that nomination, and in a secret council, Shamil had his lieutenant accused of treason and sentenced to death, on which Hadji Murad, on learning of the judgement, redefected to the Russians.[12][13] Though Shamil hoped that Britain, France, or the Ottoman Empire would come to his aid to drive Russia from the Caucasus, these plans never came to fruition. After the Crimean War, Russia redoubled its efforts against the Imamate. Now successful, Russian forces severely reduced the Imamate's territory, and by September 1859 Shamil surrendered. Though the main theater closed, conflict in the eastern Caucasus would continue for several more years.[16]

Last years

After his capture, Shamil was sent to Saint Petersburg to meet the Tsar Alexander II. Afterwards, he was exiled to Kaluga, then a small town near Moscow. After several years in Kaluga he complained to the authorities about the climate and in December, 1868 Shamil received permission to move to Kiev, a commercial center of the Empire's southwest. In Kiev he was afforded a mansion in Aleksandrovskaya Street. The Imperial authorities ordered the Kiev superintendent to keep Shamil under "strict but not overly burdensome surveillance" and allotted the city a significant sum for the needs of the exile. Shamil seemed to have liked his luxurious detainment, as well as the city; this is confirmed by the letters he sent from Kiev.[17]

In 1859 Shamil wrote to one of his sons: "By the will of the Almighty, the Absolute Governor, I have fallen into the hands of unbelievers ... the Great Emperor ... has settled me here ... in a tall spacious house with carpets and all the necessities".[18]

In 1869 he was given permission to perform the Hajj to the holy city of Mecca. He traveled first from Kiev to Odessa and then sailed to Istanbul, where he was greeted by Ottoman Sultan Abdulaziz. He became a guest at the Imperial Topkapı Palace for a short while and left Istanbul on a ship reserved for him by the Sultan. In Mecca, during the pilgrimage, he met and conversed with Abdelkader El Djezairi. After completing his pilgrimage to Mecca, he died in Medina in 1871 while visiting the city, and was buried in the Jannatul Baqi, a historical graveyard in Medina where many prominent personalities from Islamic history are interred. Two elder sons, (Cemaleddin and Muhammed Şefi), whom he had to leave in Russia in order to get permission to visit Mecca, became officers in the Russian army, while two younger sons, (Muhammed Gazi and Muhammed Kamil), served in the Turkish army whilst their daughter Peet'mat Shamil went on to marry Sheikh Mansur Fedorov, an Imam who later absconded from the Russian Empire out of fear for himself and his children's life. He fathered 11 children, one being John Fedorov who changed his name to John Federoff after migrating to Childers in Queensland, Australia[19] where he established a sugar cane farming empire.

Said Shamil, a grandson of Imam Shamil, became one of the founders of the Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus, which survived between 1917 and 1920 and later, in 1924, he established the "Committee of Independence of the Caucasus" in Germany.

Musical composition

At a gathering in 1958,[20] the Lubavitcher Rebbe told a story about a great tribal leader named Shamil, who was rebelling against the persecuting Russian forces. Lured by a false peace treaty, he was captured and imprisoned. From within his prison cell, he composed a heartfelt, wordless song emoting his rise, downfall and yearn for his eventual freedom. The song was seemingly heard by a passing Hasid, who related it to his Rebbe, who in turn adapted the tune to be easily sung in the Hasidic fashion, which was then passed down in privacy through the Chabad dynasty, until the Rebbe taught it at the above-mentioned gathering. The song uncharacteristically was adopted by the Chabad movement (who usually compose their own melodies), as they take the deeper meaning of its stanzas as an analogy for the soul, which descends to a world of mortality and physicality, trapped in a body, knowing that it will one day return to its maker.[20] (Another song uncharacteristically adapted by the Chabad movement is the tune of the La Marseillaise, which was put to the tune of the prayer Ho'aderes V'hoemunah.[21] The French government altered the tune shortly later, in 1974, only to change it back in 1981.[22])

References

- Nicholas V. Riasanovsky (1984). "Chapter 29: The Reign of Alexander II, 1855-81". A History of Russia (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 389.

- The Great Shamil, Imam of Daghestan and Chechnya, Shaykh of Naqshbandi tariqah

- http://www.vostlit.info/Texts/Dokumenty/Kavkaz/XIX/1840-1860/D_V/text1.htm Quote: fifth ancestor — Kumyk Amir-khan, a man very famous in Caucasus

- Блиев М. М. Россия и горцы Большого Кавказа: на пути к цивилизации. — М.: Мысль, 2004. — С. 279. — ISBN 5-244-01004-2.

- Халилов А. М., Идрисов М. М. Шамиль в истории Северного Кавказа и народной памяти. — Махачкала, 1998. — 119 с.

- Халилов А. М. Национально-освободительное движение горцев Северного Кавказа под предводительством Шамиля. — Махачкала: Дагучпедгиз, 1991. — 181 с.

- Quote: I do not dare to compare myself to the mighty sovereigns: I'm a simple Tatar, Shamil; but my mud, my forests and my ravines make me stronger than many sovereigns". "Я не смею равняться с могущественными государями: я простой татарин, Шамиль; но моя грязь, мои леса и ущелья делают меня сильнее многих государей". Source: "Плен у Шамиля. Правдивая повесть о восьмимесячном и шестидневном в (1854-1855 г.) пребывании в плену у Шамиля семейств: покойного генерал-маиора князя Орбелиани и подполковника князя Чавчавадзе, основанная на показаниях лиц, участвовавших в событии // Журнал для чтения воспитанникам военно-учебных заведений, Том 121. № 483. 1856"

- Т.Н. Макаров, Татарская грамматика кавказского наречия, 1848, Тифлис

- Thomas M. Barrett, At the Edge of Empire: The Terek Cossacks and the North Caucasus Frontier, 1700–1860 (Westview Press, 1999), 193.

- Daniel R. Brower and Edward J. Lazzerinini, eds., Russia's Orient: Imperial Borderlands and Peoples, 1700–1917 (Indiana University Press, 1997), 92.

- Invisible armies: Blanch, sabres("bare":70; "wild beast"; al-Qarakhi, shining (pulled out sword: 22);

- Gary Hamburg, Thomas Sanders, Ernest Tucker (eds,),Russian-Muslim Confrontation in the Caucasus: Alternative Visions of the conflict between Imam Shamil and the Russians, 1830-1859, RoutledgeCurzon 2004 pèassim

- Malise Ruthven,'Terror:The Hidden Source, in New York Review of Books October 24, 2013 pp.20-24, p.20.

- King, Charles (2008). The Ghost of Freedom. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 79–80.

- Gammer, Moshe (September 2013). "Empire and Mountains: The Case of Russia and the Caucasus". Social Evolution & History: 124–125.

- Gammer, Moshe (September 2013). "Empire and Mountains: The Case of Russia and the Caucasus". Social Evolution & History: 126.

- Андрей Манчук, Шамиль на печерских холмах Archived 2007-11-15 at the Wayback Machine, "Газета по-киевски", 06.09.2007

- Pismo Shamilia Mukhammadanu, November 24, 1859, in Omarov, ed. 100 pisem Shamilia.

- http://www.genealogy.com/forum/regional/countries/topics/russia/1461/

- "A Song - A story of bondage and freedom portrays the mystery of life". www.chabad.org. Retrieved 2018-01-01.

- "The Spiritual French Revolution: A Miracle in Our Times, 5752(1992)". www.chabad.org. Retrieved 2018-01-01.

- "La Marseillaise - background". www.marseillaise.org. Retrieved 2018-01-01.

Further reading

- Grigol Robakidze. "Imam Shamil". Kaukasische Novellen, Leipzig, 1932; Munich, 1979 (in German)

- Lesley Blanch. The Sabres of Paradise. New York: Viking Press. 1960.

- Nicholas Griffin. Caucasus: Mountain Men and Holy Wars

- Rebecca Ruth Gould. “Imam Shamil,” Russia's People of Empire: Life Stories from Eurasia, 1500 to the Present, eds. Steve Norris & Willard Sunderland (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2012), 117-128.

- Leo Tolstoy. Hadji Murat

- John F. Baddeley. The Russian conquest of the Caucasus. 1908.

- Shapi Kaziev. Imam Shamil. "Molodaya Gvardiya" publishers. Moscow, 2001, 2003, 2006, 2010. ISBN 978-5-235-03332-0

- Shapi Kaziev. Akhoulgo. Caucasian War of 19th century. The historical novel. "Epoch", Publishing house. Makhachkala, 2008. ISBN 978-5-98390-047-9

- Tamar Zigman. "The Sufi Freedom Fighter Who Inspired the Lubavitcher Rebbe", The National Library of Israel website.

External links

- Niggun Shamil, a Hassidic niggun based on Shamil's experiences

- The Great Shamil, Imam of Daghestan and Chechnya, Shaykh of Naqshbandi tariqah

- Picture of Shamil's Aul (hideout village) in Dagestan

- Colorado College Paper

- [ History of Islam in Russia]

- Portraits of Imam Shamil

- Islam in Dagestan

- The Jihad of Imam Shamil

Sister projects

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.