Japanese aircraft carrier Shōkaku

Shōkaku (Japanese: 翔鶴, "Soaring Crane") was an aircraft carrier of the Imperial Japanese Navy, the lead ship of her class. Along with her sister ship Zuikaku, she took part in several key naval battles during the Pacific War, including the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Battle of the Coral Sea and the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands before being torpedoed and sunk by a U.S. submarine at the Battle of the Philippine Sea.[2]

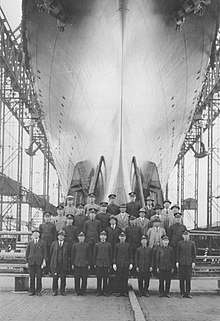

Shōkaku upon completion, 23 August 1941 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Shōkaku |

| Namesake: | 翔鶴, "Soaring Crane" |

| Laid down: | 12 December 1937 |

| Launched: | 1 June 1939 |

| Commissioned: | 8 August 1941 |

| Fate: | Sunk by American submarine USS Cavalla on 19 June 1944 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Shōkaku-class aircraft carrier |

| Displacement: |

|

| Length: | 257.5 m (844 ft 10 in) |

| Beam: | 26 m (85 ft 4 in) |

| Draft: | 8.8 m (28 ft 10 in) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 34.2 kn (63.3 km/h; 39.4 mph) |

| Range: | 9,700 nmi (18,000 km; 11,200 mi) at 18 kn (33 km/h; 21 mph) |

| Complement: | 1,660 |

| Armament: |

|

| Aircraft carried: |

|

Design

The Shōkaku-class carriers were part of the same program that also included the Yamato-class battleships. No longer restricted by the provisions of the Washington Naval Treaty, which expired in December 1936, the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) was free to incorporate all those features they deemed most desirable in an aircraft carrier, namely high speed, a long radius of action, heavy protection and a large aircraft capacity. Shōkaku was laid down at Yokosuka Dockyard on 12 December 1937, launched on 1 June 1939, and commissioned on 8 August 1941.

With an efficient modern design, a displacement of about 32,000 long tons (33,000 t), and a top speed of 34 kn (63 km/h; 39 mph), Shōkaku could carry 70–80 aircraft. Her enhanced protection compared favorably to that of contemporary Allied aircraft carriers and enabled Shōkaku to survive serious damage during the battles of the Coral Sea and Santa Cruz.[3]

Hull

In appearance, Shōkaku resembled an enlarged Hiryū, though with a 35.3 m (116 ft) longer overall length, 4.6 m (15 ft) wider beam and a larger island. As in Hiryū, the forecastle was raised to the level of the upper hangar deck to improve seakeeping. She also had a wider, more rounded and heavily flared bow which kept the flight deck dry in most sea conditions.[4]

The carrier's forefoot was of the newly developed bulbous type, sometimes referred to informally as a Taylor pear, which served to reduce the hull's underwater drag within a given range of speeds, improving both the ship's speed and endurance. Unlike the larger bulbous forefoots fitted to the battleships Yamato and Musashi, however, Shōkaku's did not protrude beyond the ship's stem.[4]

Shōkaku was 10,000 tons heavier than Sōryū, mainly due to the extra armor incorporated into the ship's design. Vertical protection consisted of 215 mm (8.5 in) on the main armor deck over the machinery, magazines and aviation fuel tanks while horizontal protection consisted of 215 mm (8.5 in) along the waterline belt abreast the machinery spaces reducing to 150 mm (5.9 in) outboard of the magazines[4]

Unlike British carriers, whose aviation fuel was stored in separate cylinders or coffer-dams surrounded by seawater, all pre-war Japanese carriers had their aviation fuel tanks built integral with the ship's hull and Shōkaku was no exception. The dangers this posed, however, did not become evident until wartime experience demonstrated these were often prone to cracking and leaking as the shocks and stresses of hits or near-misses to the carrier's hull were inevitably transferred to and absorbed by the fuel tanks. Following the debacle at Midway in mid-1942, the empty air spaces around Shōkaku's aviation fuel tanks, normally pumped full of inert carbon dioxide, were instead filled with concrete in an attempt to protect them from possible damage. But this did little to prevent volatile fumes spreading to the hangar decks in the event damage did occur, particularly demonstrated when Cavalla torpedoed and sank her. Shōkaku normally stowed 150,000 gallons of avgas for operational use.[5]

Machinery

The geared turbines installed on Shōkaku were essentially the same as those on Sōryū, maximum power increasing by 8,000 shp (6,000 kW) to 160,000 shp (120,000 kW). In spite of all the additional armor, greater displacement and a 2.1 m (6.9 ft) increase in draught, Shōkaku was able to attain a speed of just over 34.2 kn (63.3 km/h; 39.4 mph) during trials. Maximum fuel bunkerage was 4100 tons, giving her a radius of action of 9,700 nmi (18,000 km; 11,200 mi) at 18 kn (33 km/h; 21 mph). Two same-sized downward-curving funnels on the ship's starboard side, just abaft the island, vented exhaust gases horizontally from the boilers and were sufficiently angled to keep the flight deck free of smoke in most wind conditions.[6]

Flight deck and hangars

Shōkaku's 242 m (794 ft) long wood-planked flight deck ended short of the ship's bow and, just barely, short of the stern. It was supported by four steel pillars forward of the hangar box and by two pillars aft.

The flight deck and both hangars (upper and lower) were serviced by three elevators, the largest being the forward one at 13 m (43 ft) by 16 m (52 ft), the middle and the rear elevators measured 13 m (43 ft) by 12 m (39 ft). All three were capable of transferring aircraft weighing up to 5,000 kg (11,000 lb) and raising or lowering them took approximately 15–20 seconds.[8]

Shōkaku's nine Type 4 electrically operated arrester wires followed the same standard arrangement as that on Hiryū, three forward and six aft. They were capable of stopping a 6,000 kg (13,000 lb) aircraft at speeds of 60–78 knots (111–144 km/h; 69–90 mph). A third crash barrier was added and a light collapsible wind-break screen was installed just forward of the island.[4]

The upper hangar was 623.4 by 65.6 feet (190 by 20 m) and had an approximate height of 15.7 feet (4.8 m); the lower was 524.9 by 65.6 feet (160 by 20 m) and had an approximate height of 15.7 feet (4.8 m). Together they had an approximate total area of 75,347 square feet (7,000 m2). Hangar space was not greatly increased in comparison to Sōryū and both Shōkaku and Zuikaku could each carry just nine more aircraft than Sōryū, giving them a normal operating capacity of seventy-two plus room for twelve in reserve. Unlike on Sōryū, the reserve aircraft did not need to be kept in a state of disassembly, however, thereby shortening the time required to make them operational.[9]

After experimenting with port-side islands on two previous carriers, Akagi and Hiryū, the IJN opted to build both Shōkaku and her sister ship Zuikaku with starboard-side islands.[4]

In September 1942, a Type 21 air-warning radar was installed on Shōkaku's island atop the central fire control director, the first such device to be fitted on any Japanese carrier. The Type 21 had a "mattress" antenna and the initial prototypes were light enough that no major structural modifications were necessary. Later versions, however, were bulkier and required eventual removal of the fifth fire control director in order to accommodate the larger and heavier antenna.[4]

The presence of this radar however, undoubtedly saved Shōkaku one month later at the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, when the ship was bombed by SBD-3 Dauntless dive bombers from USS Enterprise; the early detection of the US strike planes by this radar alerted refuelling crews below deck, giving them time to drain and purge the aviation gasoline lines before they were ruptured by bomb hits, thus saving the ship from the catastrophic avgas fires and explosions that caused most of the carrier sinkings in the Pacific theater.

Armament

Shōkaku's primary air defense consisted of sixteen 127 mm (5.0 in) Type 89 dual-purpose AA guns in twin mountings. These were sited below flight deck level on projecting sponsons with four such paired batteries on either side of the ship's hull, two forward and two aft. Four fire control directors were installed, two on the port side and two to starboard. A fifth fire control director was located atop the carrier's island and could control any or all of the heavy-caliber guns as needed.[4]

Initially, light AA defense was provided by twelve triple-mount 25 mm (0.98 in) Type 96 AA guns.[4]

In June 1942, Shōkaku had her anti-aircraft armament augmented with six triple 25 mm mounts, two each at the bow and stern, and one each fore and aft of the island. The bow and stern groups each received a Type 95 director. In October another triple 25 mm mount was added at the bow and stern and 10 single mounts were added before the Battle of the Philippine Sea in June 1944.

Operational history

Shōkaku and Zuikaku formed the Japanese 5th Carrier Division, embarking their aircraft shortly before the Pearl Harbor attack. Each carrier's aircraft complement consisted of 15 Mitsubishi A6M2 "Zero" fighters, 27 Aichi D3A1 "Val" dive bombers, and 27 Nakajima B5N1 or B5N2 "Kate" torpedo bombers.

Shōkaku and Zuikaku joined the Kido Butai ("Mobile Unit/Force", the Combined Fleet's main carrier battle group) and participated in Japan's early wartime naval offensives, including Pearl Harbor and the attack on Rabaul in January 1942.

In the Indian Ocean raid of March–April 1942, aircraft from Shōkaku, along with the rest of Kido Butai, attacked Colombo, Ceylon on 5 April, sinking two ships in harbor and severely damaging support facilities. The task force also found and sank two Royal Navy heavy cruisers, (HMS Cornwall and Dorsetshire), on the same day, as well as the aircraft carrier HMS Hermes on 9 April off Batticaloa.

The Fifth Carrier Division was then deployed to Truk to support Operation Mo (the planned capture of Port Moresby in New Guinea). During this operation, Shōkaku's aircraft helped sink the American aircraft carrier USS Lexington during the Battle of the Coral Sea but was herself seriously damaged on 8 May 1942 by dive bombers from USS Yorktown and Lexington which scored three bomb hits: one on the carrier's port bow, one to starboard at the forward end of the flight deck and one just abaft the island. Fires broke out but were eventually contained and extinguished. The resulting damage required Shōkaku to return to Japan for major repairs.

On the journey back, maintaining a high speed in order to avoid a cordon of American submarines out hunting for her, the carrier shipped so much water through her damaged bow that she nearly capsized in heavy seas. She arrived at Kure on 17 May 1942 and entered drydock on 16 June 1942. Repairs were completed within ten days and, a little over two weeks later on 14 July, she was formally reassigned to Striking Force, 3rd Fleet, Carrier Division 1.[10]

The time required for repairs, combined with the aircraft and aircrew losses incurred by her and Zuikaku, kept both carriers from participating in the Battle of Midway.

Following her return to front-line duty, both Shōkaku and her sister-ship Zuikaku, with the addition of the light carrier Zuihō, were redesignated as the First Carrier Division and took part in two further battles in 1942: the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, where they damaged USS Enterprise, but Shōkaku was in turn damaged by dive-bombers of Enterprise, which therefore prevented the bombardment of nearby Henderson Field; and the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, where they crippled USS Hornet (Hornet was abandoned and later sunk by Japanese destroyers Makigumo and Akigumo). At Santa Cruz, on 26 October 1942, Shōkaku was again seriously damaged, taking at least three (and possibly as many as six) 1,000-lb. bomb hits from a group of fifteen Douglas SBD-3 dive bombers launched from Hornet. With ample warning of the incoming American strike, Shōkaku's aviation fuel mains to the flight deck and hangars had been drained down and she had few aircraft on board at the time of the attack. As a result, no major fires broke out and her seaworthiness was preserved. Her flight deck and hangars, however, were left in shambles and she was unable to conduct further air operations during the remainder of the battle.[8][11] The need for repairs kept her out of action for months, leaving other Japanese defensive operations in the Pacific lacking sufficient airpower.

After several months of repairs and training, Shōkaku, now under the command of Captain Hiroshi Matsubara, was assigned in May 1943 to a counterattack against the Aleutian Islands, but the operation was cancelled after the Allied victory at Attu. For the rest of 1943, she was based at Truk, then returned to Japan for maintenance late in the year.

Sinking

In 1944, Shōkaku was deployed to the Lingga Islands south of Singapore. On 15 June, she departed with the Mobile Fleet for Operation "A-Go", a counterattack against Allied forces in the Mariana Islands. Her strike waves suffered heavy losses from US combat air patrols and anti-aircraft fire, but some survived and returned safely to the carrier. One of her D4Y Suisei strike groups, composed of veterans from the Coral Sea and Santa Cruz engagements, broke through and one plane allegedly struck home with a bomb that damaged the battleship USS South Dakota and caused many casualties, but this group suffered heavy losses themselves. During the Battle of the Philippine Sea, she was struck at 11:22 on 19 June by three (possibly four) torpedoes from the submarine USS Cavalla, under Commander Herman J. Kossler. As Shōkaku had been in the process of refueling and rearming aircraft and was in an extremely vulnerable condition, the torpedoes started fires that proved impossible to control. At 12:10, an aerial bomb exploded, detonating aviation fuel vapors which had spread throughout the ship. The order to abandon ship was given, but before the evacuation had progressed very far, Shōkaku abruptly took on water forward and sank quickly bow-first at position 11°40′N 137°40′E, taking 1,272 men with her. The light cruiser Yahagi and destroyers Urakaze, Wakatsuki, and Hatsuzuki rescued Captain Matsubara and 570 men.[2]

Gallery

Mitsubishi A6M2 "Zero" fighters (fighter division commander : Tadashi Kaneko ) from the Shōkaku preparing for the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Mitsubishi A6M2 "Zero" fighters (fighter division commander : Tadashi Kaneko ) from the Shōkaku preparing for the attack on Pearl Harbor.

See also

- List by death toll of ships sunk by submarines

Notes

- Bōeichō Bōei Kenshūjo, p. 344

- "Japanese Navy Ships – Shokaku (Aircraft Carrier, 1941–1944)". U.S. Naval Historical Center. 4 June 2000. Retrieved 13 February 2008.

- Stille, p.17

- Brown, p.23

- Brown, p.6

- Brown, p.23–24

- Brown, p.24

- Stille, p.18

- Stille, p.21

- "Japanese Repair Ships". www.combinedfleet.com.

Bibliography

- Bōeichō Bōei Kenshūjo (1967), Senshi Sōsho Hawai Sakusen. Tokyo: Asagumo Shimbunsha.

- Brown, David (1977). WWII Fact Files: Aircraft Carriers. Arco Publishing. ISBN 0-668-04164-1.

- Chesneau, Roger (1998). Aircraft Carriers of the World, 1914 to the Present. Brockhampton Press. ISBN 1-86019-875-9.

- Dickson, W. David (1977). "Fighting Flat-tops: The Shokakus". Warship International. Toledo, Ohio: International Naval Research Organization. XIV (1): 15–46.

- Dull, Paul S. (1978). A Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy (1941–1945). Naval Institute Press.

- Hammel, Eric (1987). Guadalcanal: The Carrier Battles. Crown Publishers, Inc. ISBN 0-517-56608-7.

- Jentschura, Hansgeorg; Jung, Dieter & Mickel, Peter (1977). Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. ISBN 0-87021-893-X.

- Lengerer, Hans (2014). "The Aircraft Carriers of the Shōkaku Class". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2015. London: Conway. pp. 90–109. ISBN 978-1-84486-276-4.

- Lundstrom, John B. (2005a). The First Team: Pacific Naval Air Combat from Pearl Harbor to Midway (New ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-471-X.

- Lundstrom, John B. (2005b). The First Team and the Guadalcanal Campaign. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-526-8.

- Peattie, Mark (2001). Sunburst: The Rise of Japanese Naval Air Power 1909–1941. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-432-6.

- Polmar, Norman & Genda, Minoru (2006). Aircraft Carriers: A History of Carrier Aviation and Its Influence on World Events. Volume 1, 1909–1945. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books. ISBN 1-57488-663-0.

- Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two (Third Revised ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-119-2.

- Shores, Christopher; Cull, Brian & Izawa, Yasuho (1992). Bloody Shambles. I: The Drift to War to the Fall of Singapore. London: Grub Street. ISBN 0-948817-50-X.

- Shores, Christopher; Cull, Brian & Izawa, Yasuho (1993). Bloody Shambles. II: The Defence of Sumatra to the Fall of Burma. London: Grub Street. ISBN 0-948817-67-4.

- Stille, Mark (2009). The Coral Sea 1942: The First Carrier Battle. Campaign. 214. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84908-106-1.

- Stille, Mark (2011). Tora! Tora! Tora:! Pearl Harbor 1941. Raid. 26. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84908-509-0.

- Stille, Mark (2007). USN Carriers vs IJN Carriers: The Pacific 1942. Duel. 6. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-248-6.

- Tully, Anthony P. (30 July 2010). "IJN Shokaku: Tabular Record of Movement". Kido Butai. Combinedfleet.com. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- Tully, Anthony; Parshall, Jon & Wolff, Richard. "The Sinking of Shokaku -- An Analysis". Kido Butai. Combinedfleet.com. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- Zimm, Alan D. (2011). Attack on Pearl Harbor: Strategy, Combat, Myths, Deceptions. Havertown, Pennsylvania: Casemate Publishers. ISBN 978-1-61200-010-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shōkaku. |

- US Navy photos of Shokaku

- Tabular record of movement from combinedfleet.com

- Anthony Tully, Jon Parshall and Richard Wolff, The Sinking of Shokaku — An Analysis