United States declaration of war on Japan

On December 8, 1941, the United States Congress declared war (Pub.L. 77–328, 55 Stat. 795) on the Empire of Japan in response to that country's surprise attack on Pearl Harbor the prior day. It was formulated an hour after the Infamy Speech of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Japan had sent a message to their embassy in Washington, but because of problems in decoding and typing out the very long message – the high-security level assigned to the declaration meant that only personnel with very high clearances could decode it, which slowed the process – it was not delivered to the U.S. Secretary of State until after the Pearl Harbor attack. Following the U.S. declaration, Japan's allies, Germany and Italy, declared war on the United States, bringing the United States fully into World War II.

.svg.png) | |

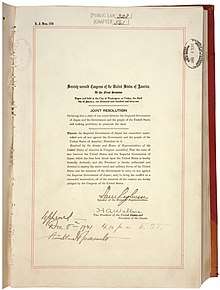

| Long title | "Joint Resolution Declaring that a state of war exists between the Imperial Government of Japan and the Government and the people of the United States and making provisions to prosecute the same." |

|---|---|

| Enacted by | the 77th United States Congress |

| Effective | December 8, 1941 |

| Citations | |

| Public law | Pub.L. 77–328 |

| Statutes at Large | 55 Stat. 795 |

| Legislative history | |

| |

Background

The attack on Pearl Harbor took place before a declaration of war by Japan had been delivered to the United States. It was originally stipulated that the attack should not commence until thirty minutes after Japan had informed the U.S. that it was withdrawing from further peace negotiations,[1][2] but the attack began before the notice could be delivered. Tokyo transmitted the 5,000-word notification – known as the "14-Part Message" – in two blocks to the Japanese Embassy in Washington. However, because of the very secret nature of the message, it had to be decoded, translated and typed up by high embassy officials, who were unable to do these tasks in the available time. Hence, the ambassador did not deliver it until after the attack had begun. But even if it had been, the notification was worded so that it actually neither declared war nor severed diplomatic relations, so it was not a proper declaration of war as required by diplomatic traditions.[3]

The United Kingdom declared war on Japan nine hours before the U.S. did, partially due to Japanese attacks on the British colonies of Malaya, Singapore, and Hong Kong; and partially due to Winston Churchill's promise to declare war "within the hour" of a Japanese attack on the United States.[4]

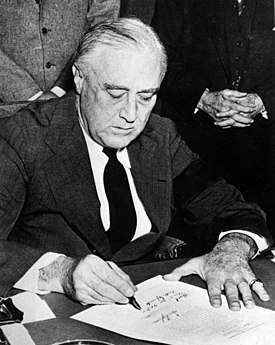

Vote and Presidential signature

President Roosevelt formally requested the declaration in his Infamy Speech, addressed to a joint session of Congress and the nation at 12:30 p.m. on December 8.[5] The declaration was quickly brought to a vote; it passed the Senate, and then passed the House at 1:10 p.m.[5] The vote was 82–0 in the Senate and 388–1 in the House. Jeannette Rankin, a pacifist and the first woman elected to Congress (in 1916), cast the only vote against the declaration, eliciting hisses from some of her peers. Several colleagues pressed her to change her vote to make the resolution unanimous—or at least to abstain—but she refused.[6][7] "As a woman, I can't go to war," she said, "and I refuse to send anyone else." Nine other women held Congressional seats at the time. After the vote, reporters followed her into the Republican cloakroom, where she refused to make any comments and took refuge in a telephone booth until United States Capitol Police cleared the cloakroom.[8] Two days later, a similar war declaration against Germany and Italy came to vote; Rankin abstained. Nine other women voted in favor of the declaration of war.

Roosevelt signed the declaration at 4:10 p.m the same day.[5] The power to declare war is assigned exclusively to Congress in the United States Constitution, making it an open question whether his signature was technically necessary.[5] However, his signature was symbolically powerful and resolved any doubts.

Text of the declaration

Whereas the Imperial Government of Japan has committed unprovoked acts of war against the Government and the people of the United States of America:

Therefore be it Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That the state of war between the United States and the Imperial Government of Japan which has thus been thrust upon the United States is hereby formally declared; and the President is hereby authorized and directed to employ the entire naval and military forces of the United States and the resources of the Government to carry on war against the Imperial Government of Japan; and, to bring the conflict to a successful termination, all the resources of the country are hereby pledged by the Congress of the United States.[9]See also

References

- Hixson, Walter L. (2003), The American Experience in World War II: The United States and the road to war in Europe, Taylor & Francis, p. 73, ISBN 978-0-415-94029-0

- Calvocoressi, Peter; Wint, Guy & Pritchard, John (1999) The Penguin History of the Second World War, London: Penguin. p.952

- Prange, Gordon W. (1982) At Dawn We Slept: The Untold Story of Pearl Harbor, Dillon. pp.424, 475, 493-94

- Staff (December 15, 1941) "The U.S. At War, The Last Stage" Time

- Kluckhorn, Frank L.(December 9, 1941) "U.S. Declares War, Pacific Battle Widens" The New York Times p.A1. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- Staff (April 1, 2014) "Jeannette Rankin: Suffragist, Congresswoman, Pacifist" Women's History Matters

- Luckowski, Jean and Lopach, James (ndg) "A Chronology and Primary Sources for Teaching about Jeannette Rankin" Montana.gov

- "Miss Rankin Is Lone Dissenter in War Vote". The Milwaukee Sentinel. December 9, 1941. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- "Declaration of War with Japan" Retrieved 2010-15-7