Seventh-day Adventist Church in Tonga

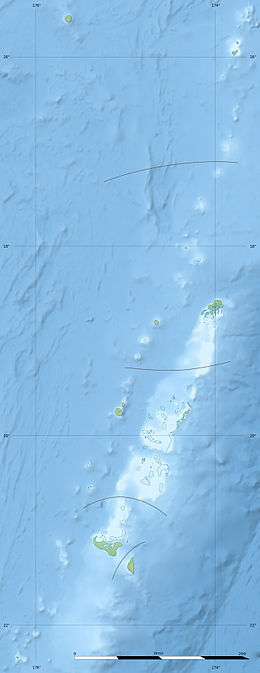

The Seventh-day Adventist Church in Tonga, (Tongan: Siasi ʻAhofitu) is one of the smaller religious groups in the South Pacific island state of Tonga[1] with over 3,599 members as of June 30, 2018,[2] started by Seventh-day Adventist missionaries from the United States who visited in 1891 and settled in 1895. They set up schools but made very little progress in conversion, handicapped by dietary rules that prohibited popular local foods such as pork and shellfish, and that also banned tobacco, alcohol and kava.

| Seventh-day Adventist Church in Tonga | |

|---|---|

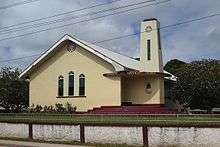

Main church of Seventh-day Adventists in Nukuʻalofa, Tonga | |

| |

| 21.195093°S 175.176341°W | |

| Country | Tonga |

| Denomination | Seventh-day Adventist |

| History | |

| Founded | 1895 |

| Founder(s) | Edward Hilliard |

The church was revitalized in 1912 with renewed emphasis on evangelism. In 1922 it resumed its strategy of providing education, which resulted in an increase in conversions. After keeping a low profile during World War II (1939–45), the church grew quickly from 1950 to the 1970s. However, membership subsequently declined due to emigration and competition with other churches. The SDA of Tonga is part of the South Pacific Division of Seventh-day Adventists. It operates several schools in Tonga, and provides opportunities for further studies at Adventist institutions abroad.

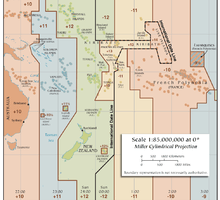

Tonga lies to the east of the 180° meridian but to the west of the International Date Line (IDL), in the time zone UTC+13:00. Seventh-day Adventists typically observe the Sabbath on Saturday. The SDA Church determines that in Tonga the Sabbath is observed as if the IDL ran along the 180° meridian and the time zone were UTC−12:00, so it observes the Sabbath on Sunday.

History

The Seventh-day Adventist church in Tonga took almost twenty years to become established.[3] The SDA is against dancing, and smoking is grounds for being expelled from the church. The SDA is stricter than other churches in observing the Sabbath.[4][5] In the early years the insistence on eating only "clean" foods and abstaining from tobacco and alcohol were obstacles to conversion.[6] Their refusal to eat pork or shellfish[lower-alpha 1] meant they could not eat at feasts or in the presence of chiefs, and therefore could not actively evangelize.[8] The use of kava was a double problem, since this widely used drug was seen as akin to alcohol, and also had ceremonial and traditional religious connotations, but to refuse a cup of kava is to insult the giver.[9]

Background

Seventh-day Adventists became active in the South Pacific in 1886 when the missionary John Tay visited the Pitcairn Islands. His report caused the Seventh-day Adventist church in the United States to build the Pitcairn mission ship, which made six voyages in the 1890s, bringing missionaries to the Society Islands, Cook Islands, Samoa, Tonga and Fiji.[10] On its first voyage, the Pitcairn visited almost every "white family" in the Tongan islands, and sold books worth more than $500.[11][lower-alpha 2] In June 1891, E. H. Gates and A. J. Read visited Tonga, then called the Friendly Islands, on the fourth journey of the Pitcairn.[13] King George Tupou I (c. 1797 – 18 February 1893) authorized the entry of the missionaries.[14] They left without making any Adventist converts.[13]

Initial work 1895–1912

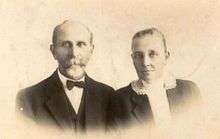

The SDA missionary Edward Hilliard, his wife Ida, and daughter Alta arrived at Nukuʻalofa on 30 August 1895.[15] Ida Hilliard was a teacher, and started a small school late in 1895. At its peak the school had 28 pupils, paying $3 per quarter. The school closed in mid-1899 just before the Hilliards left the islands for Australia.[15][lower-alpha 3] Edward Hilliard earned an income as a carpenter. He understood the importance of learning the local language, and translated some religious tracts into the Tongan language.[21] He was no longer young and found the language difficult. He seems to have focused on converting Europeans.[22]

On 29 September 1896, more Adventist missionaries arrived in Tonga on the Pitcairn, including Sarah[lower-alpha 4] and Maria Young, two nursing trainees from Pitcairn Island, and Edwin and Florence Butz with their daughter Alma. The Butz family initially had difficulty being accepted, as they were Americans and most European residents were British. This was eased by Florence Butz' provision of medical services.[24] In September 1897 Doctor Merritt Kellogg and his wife Eleanor Nolan came to assist with the medical work. He built a timber home at Magaia that was long used as the home of the mission superintendent.[21]

The Butz's tried to establish a permanent mission, but were mainly limited to working with the small papalagi (European) colony. They made sporadic missionary efforts in the islands of Haʻapai and Tongatapu.[14] In June 1899 the Pitcairn again visited, bringing a small prefabricated building that was used at first as a mission home and as a chapel. After 18 months it was taken apart and rebuilt as the small Nuku'alofa church, 5 by 10 metres (16 by 33 ft).[21] The church almost failed to survive.[14] The Butz's were taken to Vavaʻu on the Pitcairn, since it was thought that there were too many missionaries at Nuku'alofa, but they returned after the Hilliards left later in 1899.[21]

First results 1899–1912

The first European was baptized on 10 September 1899, on the day that the first Adventist Church in Tonga was organized.[24] He was Charles Edwards, an Englishman and a reformed drinker. He was a medical assistant who also managed the finances and records of the church of Nuku'alofa for many years.[21] Edwards married Maria Young soon after his baptism.[21] Maria helped when Queen Lavinia gave birth to Sālote Tupou III (13 March 1900 – 16 December 1965). Sālote later became queen of Tonga.[25][lower-alpha 5] Timote Mafi was the first Tongan Adventist convert.[29] She was baptized on 22 December 1900, along with her European husband.[24]

The English missionary Shirley Waldemar Baker, founder of the Free Wesleyan Church of Tonga in 1885, fell out with the authorities due to his intrigues to obtain German "protection" for Tonga. When he died in Haʻapai a visiting SDA minister officiated at his burial in 1903 after the Free Church, Wesleyans, Catholics and Anglicans all refused to give him a funeral.[30]

In November 1904 Ella Boyd reopened the Adventist primary school at Nukuʻalofa. She was an American who had trained at the Avondale College in Australia, and had taught in church schools in Australia. By 1905 the school had reached its full capacity of 28 pupils.[31] The school charged pupils 20¢ per week. The curriculum emphasized health, and warned of the evils of narcotics and stimulants.[32] Butz recognized but failed to address the language problem. He noted that the Tongans were very interested in learning English. Until 1905 at least half of the pupils at the Adventist schools were European, or partly European, and the lessons were given in English.[22]

The Butz family left on 27 December 1905. In ten years Butz had baptized two Tongans and twelve Europeans. In the next seven years just one person was baptized at Nuku'alofa, Joni Latu, in 1910. He later became an SDA minister.[32] For a while the Nukuʻalofa school thrived, reaching about sixty pupils in 1907.[33] Another school was established at Faleloa in 1908, with thirty students.[34] An Adventist leader who visited Faleloa in 1908 wrote that the school was a "credit to our school work not only in Tonga, but throughout the Australasian field."[35] The monthly Tongan-language Talafekau Moʻoni (Faithful Messenger) began to appear in 1909. It was mostly written by Frances Waugh, the translator at Avondale Press, and Tongan students at the Avondale School.[36] Some members of the royal family patronized the SDA school, but the church suffered from emigration and lapses.[14] By 1911 the school at Faleloa was almost deserted and there were just eighteen students remaining at Nukuʻalofa.[37] That year both schools closed.[35]

Relaunch and growth 1912–45

In 1912, George G. Stewart and his wife Grace reestablished the mission.[14] Stewart, who arrived early in 1912, reported that Adventist work was "practically at a standstill."[38] He and the Ethelbert Thorpe family changed the emphasis of the mission from education to evangelism.[39] The church was now better organized for work in the Pacific, with bases in New Zealand and Australia.[14] Stewart rebuilt the Falaloa school, which had been badly damaged by a hurricane, and started revival meetings in an effort to improve standards of worship.[36] The missionaries used the Tongan language, and their school at Nukuʻalofa under Maggie Ferguson attracted Tongan pupils eager to obtain education.[14] By June 1915 the SDA Church in Tonga had fourteen Tongan members.[39] In 1917 the mission home at Faleloa was expanded to provide accommodation for female pupils at the Faleloa school, which by then had a total of about forty pupils.[40] By 1918 the school had sixty pupils.[41]

The 1918 flu pandemic caused a major set-back, and the missionary Pearl Tolhurst died. The SDA concluded that its future success would depend on development of its schools.[14] Robert and Frances Smith came from Hawaii in 1920, and supervised the mission until 1927.[42] The mission was formally organized as the Tonga Mission in 1921. The next year, the South Pacific Division of Seventh-day Adventists was founded.[43] The school at Nuku'alofa was reopened with about forty pupils, and a government teacher from Australia joined the mission. Bible classes were given in Tongan by Joni Latu. The mission bought a small boat named Talafekau (Messenger) for the Faleloa missionaries. The Talafekau Mo'oni magazine was relaunched in January 1922, printed bi-monthly in Fiji, and a 50-song hymnal in Tongan was also printed. The first camp meeting was held in June 1922 at Nuku'alofa, attended by members of the Faleloa and Neiafu churches.[44]

Growth in the Tongan mission after the 1920s was largely due to converts among pupils at the SDA schools, especially those of Maggie Ferguson. In 1930, 75% of Tongan Adventists had been converted by the schools.[45] A training center for mission workers was established at Vaini in January 1926.[44] The training school, later called Beulah College, formed the basis for rapid growth from the 1950s to the 1970s. About half the students of Beulah College were non-SDA, but many of these were baptized.[45] In 1937 the school was formally recognized by the government, based on the success of its pupils in public exams.[13] In the mid-1930s, the government passed a law that all college students must attend church on the Sabbath. A group of students at Tonga College decided to worship at the nearby SDA church at Mangaia, and many of them joined the Adventists.[46]

During World War II (1939–45) the Seventh-day Adventists kept a low profile in Tonga and grew slowly. As conscientious objectors, they could not fight during the war, which they interpreted as heralding the Last Days when Christ would return. They had good relations with Queen Sālote but were viewed as outsiders.[8] From 1940 there are few reports on SDA medical work in Tonga.[47]

Post World War II

Until 1946, the total membership of the SDA on Niue and Tonga was never more than 100. However, after the war, the SDA grew rapidly on Tonga, along with most other Pacific Island groups.[48] By the 1960s, the threshold for baptism had slipped, with baptism approved for those who had only renounced use of alcohol and tobacco a few hours earlier.[49] After the 1970s, growth in SDA membership in Tonga slowed sharply due to emigration and competition from other churches.[50] As of 2012, SDA members made up just 2% of the population, among other groups including Free Wesleyan (37%), Church of the Latter-Day Saints (17%), Roman Catholic (16%), Free Church of Tonga (11%), Church of Tonga (8%) and Anglican (1%).[51]

Education

Helen Morton notes in her 1996 book on Tonga that education in highly valued in Tonga but teaching is a relatively low-status occupation. The Seventh-day Adventist schools are funded from abroad—unlike other schools in Tonga—have new buildings, sports facilities, modern textbooks and equipment, and arrange extracurricular activities for their pupils.[52] There are four Seventh-day Adventist schools in Tonga: Beulah Primary School, the Hilliard and Mizpah integrated primary and middle schools, and the secondary Beulah Adventist College. Students of Beulah College sat for the University Entrance exam for the first time in 1986.[13]

Students from Tonga may go on to Longburn Adventist College in New Zealand. Small numbers go to Sydney Adventist Hospital for training as nurses. John Kamea of Tonga studied at the Avondale College at Cooranbong, New South Wales before World War II, and later Enoke Hema of Tonga studied at Avondale.[53] The Pacific Adventist University in Boroko, Papua New Guinea also accepts students from all Pacific islands, including Tonga, mainly SDA adherents.[54]

Health

In 2000 the SDA was operating a mobile clinic that promoted family planning.[55]

Date Line controversy

The Sabbath in seventh-day churches is observed on the seventh day of the week, typically from sunset on Friday until sunset on Saturday. This is an important part of the beliefs and practices of the church.[56] Kellogg, Butz and Hilliard debated which was the correct day to observe the Sabbath in Tonga. The practice on the Pitcairn had been to change days at the 180° meridian. Islands such as Samoa and Tonga were well to the east of this line, so the missionaries observed the Sabbath on the day sequence of the Western Hemisphere. However, the Tonga islands used the same days as New Zealand and Australia, so the missionaries were observing the seventh-day Sabbath on Sunday.[57][lower-alpha 6]

The tract by Adventist John N. Andrews entitled The Definitive Seventh Day (1871) recommended using a Bering Strait date line.[57] If this was accepted, the Tonga Adventists were celebrating the Sabbath on the wrong day. However, an international conference in 1884 established the International Date Line (IDL) at 180° while allowing for local adjustments.[59] The Tonga missionaries sent letters to church leaders in Tahiti, Australia and the U.S. asking for advice, and even asked Ellen G. White for her opinion.[57] Replies were contradictory. It was not until 1901 that White sent a letter to Kellogg but her reply did not answer the question, it simply stated it was not his task to solve the problem of the dayline.[59] Time, circumstances and practice led to the 180° meridian being imposed by the Adventists as the IDL, and the SDA church in Tonga observes the Sabbath on Sunday. Historian, Kenneth Bain, in his 1967 book, The Friendly Islanders, claimed that SDA adherence to the 180 degree meridian is a face saving compromise which their pioneer missionaries searched out because the nation had strict Sunday laws. In 1970, Robert Leo Odom's book, The Lord's Day On A Round World was reissued by the Church with added chapters covering the Church's Sunday observance in Tonga.[4][5]

In 1995, the time zone of Kiribati was changed so Adventists on the Phoenix and Line Islands observe Sunday. In 2011, the time zone of Samoa was changed to align the working week with that of Australia and New Zealand, placing these countries in the same time zone as Tonga. In August 2012, the SDA of Samoa confirmed that it would follow the example of Tonga and officially observe the Sabbath on Sunday rather than move the Sabbath in accordance with the changed time zone.[60]

See also

- Australian Union Conference of Seventh-day Adventists

- Seventh-day Adventist Church in Brazil

- Seventh-day Adventist Church in Canada

- Seventh-day Adventist Church in the People's Republic of China

- Seventh-day Adventist Church in Colombia

- Seventh-day Adventist Church in Cuba

- Seventh-day Adventist Church in India

- Italian Union of Seventh-day Adventist Churches

- Seventh-day Adventist Church in Ghana

- New Zealand Pacific Union Conference of Seventh-day Adventists

- Seventh-day Adventist Church in Nigeria

- Adventism in Norway

- Romanian Union Conference of Seventh-day Adventists

- Seventh-day Adventist Church in Sweden

- Seventh-day Adventist Church in Thailand

- Seventh-day Adventists in Turks and Caicos Islands

References

- Goat meat is deemed clean by Adventists, who are known in Tonga as kaikosi, or goat-eaters.[7]

- In 1900 US $1.00 was worth about UK 4/-, so $500 would have been about £100.[12]

- Other missionary groups ran schools in Tonga. One source says the first was built in 1829 by the Wesleyan missionary William Lawry.[16] Another source says the first Methodist school was opened at Nuku'alofa on 17 March 1828.[17] The Methodist Tupou College in Toloa, Tongatapu is the oldest secondary school in the Pacific Islands, established in 1866.[18] Although Old Tungī Halatuituia was a member of the Free Church, after his death in 1900 his widow ʻEsetia sent Viliami Tungī Mailefihi to the Catholic school at Maʻufanga.[19] The future queen Sālote Tupou III was sent to the Anglican Diocesan School for Girls in Epsom, a suburb of Auckland, New Zealand.[20]

- Sarah Young left Tonga in 1899 with the Hilliards. She attended the first course for medical missionaries given at the Avondale Retreat in Cooranbong, New South Wales, and soon after began work in Samoa. Her sister was Rosalind Amelia Young, the author.[23]

- On her accession as queen, Salote affirmed that she would rule as a constitutional monarch.[26] However, the parliament was not as strong as in Britain.[27] Sālote retained the rights to appoint and dismiss her ministers.[28]

- Governments are free to select the time zone of their choice. The International Date Line (IDL) was placed east of Tonga to align its weekdays with New Zealand and Fiji. Consequently, Tonga's time zone is UTC+13 rather than UTC−12:00, as it would be if the Date Line ran along the 180° meridian.[58] However, the SDA church observes the Sabbath as though the IDL followed the 180° meridian.[56]

- Seventh-day Adventist Membership:Countries Compared NationMaster Retrieved December 3, 2018

- Adventist Directory Retrieved March 19, 2019

- Steley 1989, p. 59.

- Lal & Fortune 2000, p. 199.

- Stanley 1999, p. 205.

- Steley 1989, p. 207.

- Steley 1989, p. 205.

- Garrett 1997, p. 92.

- Steley 1989, p. 209.

- Finau, Leuti & Langi 1992, p. 88.

- Steley 1989, p. 75.

- Dimson, Marsh & Staunton 2009, p. 95.

- Piula College, Tonga on the 'NET.

- Garrett 1992, p. 150.

- Hook 2007, p. 2.

- Stanley 1999, p. 198.

- Latukefu 1969, p. 103.

- Tupou College, Tonga on the 'NET.

- Wood-Ellem 1999, p. 42.

- Wood-Ellem 1999, p. 13.

- Hook 2007, p. 3.

- Steley 1989, p. 77.

- Steley 1989, p. 82.

- Steley 1989, p. 76.

- Ferch 1986.

- Wood-Ellem 1999, p. 70.

- Wood-Ellem 1999, p. 182.

- Wood-Ellem 1999, p. 137.

- Maxwell 1966.

- Garrett 1992, p. 143.

- Hook 2007, p. 6.

- Hook 2007, p. 7.

- Hook 2007, p. 8.

- Hook 2007, p. 9.

- Steley 1989, p. 78.

- Hook 2007, p. 11.

- Hook 2007, p. 10.

- Steley 1989, p. 78–79.

- Steley 1989, p. 79.

- Hook 2007, p. 15.

- Hook 2007, p. 16.

- Hook 2007, p. 17.

- Melton 2014, p. 1610.

- Hook 2007, p. 18.

- Steley 1989, p. 125.

- Steley 1989, p. 160–161.

- Steley 1989, p. 133.

- Hook 2007, p. 19–20.

- Steley 1989, p. 153.

- Steley 1989, p. 161.

- Soboslai 2011, p. 1294.

- Morton 1996, p. 39.

- Crocombe & Meleisea 1988, p. 230.

- Crocombe & Meleisea 1988, p. 391.

- Morton 1996, p. 52.

- Burnside 1966.

- Hay 1990, p. 4.

- Greene 2002, p. 80.

- Hay 1990, p. 5.

- Date shift causes confusion... Radio Australia 2012.

Sources

- Burnside, G. (January 1966). "Why Seventh-day Adventists Keep Sunday in Tonga". Ministry. Retrieved 2015-01-23.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Crocombe, Ron; Meleisea, Malama (1988). Pacific Universities: Achievements, Problems, Prospects. University of the South Pacific - Institute of Pacific Studies. ISBN 978-982-02-0039-5. Retrieved 2015-01-22.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Date shift causes confusion for churches in Samoa". Radio Australia. 14 August 2012. Retrieved 2015-01-23.

- Dimson, Elroy; Marsh, Paul; Staunton, Mike (2009-04-11). Triumph of the Optimists: 101 Years of Global Investment Returns. Princeton University Press. ISBN 1-4008-2947-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ferch, Arthur J., ed. (1986). Symposium on Adventist History in the South Pacific: 1885-1918. Warburton, Australia: Sign Pub. Co.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Finau, Makisi; Leuti, Teeruro; Langi, Jione (1992). Island Churches: Challenge and Change. University of the South Pacific - Institute of Pacific Studies. ISBN 978-982-02-0077-7. Retrieved 2015-01-21.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Garrett, John (1992). Footsteps in the Sea: Christianity in Oceania to World War II. editorips@usp.ac.fj. ISBN 978-982-02-0068-5. Retrieved 2015-01-22.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Garrett, John (1997). Where Nets Were Cast: Christianity in Oceania Since World War II. University of the South Pacific - Institute of Pacific Studies. ISBN 978-982-02-0121-7. Retrieved 2015-01-21.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Greene, David (2002-09-01). Light and Dark: An exploration in science, nature, art and technology. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-3403-5. Retrieved 2015-01-24.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hay, David E. (1990-01-27). "Mettitt Kellogg and the Pacific Dilemma" (PDF). Record. Retrieved 2015-01-27.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hook, Milton (2007). TALAFEKAU MO’ONI – EARLY ADVENTISM IN TONGA AND NIUE (PDF). South Pacific Division Department of Education. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-03-24. Retrieved 2015-01-21.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lal, Brij V.; Fortune, Kate (2000). The Pacific Islands: An Encyclopedia. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2265-1. Retrieved 2015-01-21.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Latukefu, Sione (1969). "The case of the Wesleyan Mission in Tonga". Journal de la Société des océanistes. 25. Retrieved 2015-01-24.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Maxwell, Arthur S. (1966). Under the Southern Cross. Nashville, TN: Southern Publishing Association.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Piula College", Tonga on the 'NET, archived from the original on 2011-07-18, retrieved 2015-01-21

- Melton, J. Gordon (2014-01-15). Faiths Across Time: 5,000 Years of Religious History. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-61069-026-3. Retrieved 2015-01-22.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morton, Helen Lee (1996-01-01). Becoming Tongan: An Ethnography of Childhood. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1795-4. Retrieved 2015-01-21.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Soboslai, John (2011-10-18). "Tonga". Encyclopedia of Global Religion. SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-1-4522-6656-5. Retrieved 2015-01-22.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stanley, David (1999). Tonga-Samoa Handbook. David Stanley. ISBN 978-1-56691-174-0. Retrieved 2015-01-24.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Steley, Dennis (1989), Unfinished: The Seventh-day Adventist Mission in the South Pacific, Excluding Papus New Guinea, 1886 - 1986, University of Auckland, retrieved 2015-01-22CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Tupou College". Tonga on the 'NET. Retrieved 2015-01-24.

- Wood-Ellem, Elizabeth (1999). Queen S_lote of Tonga: The Story of an Era 1900-1965. Auckland University Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2529-4. Retrieved 2015-01-24.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)