Serpico

Serpico is a 1973 American neo-noir[5][6] biographical crime film directed by Sidney Lumet, and starring Al Pacino. Waldo Salt and Norman Wexler wrote the screenplay, adapting Peter Maas's biography of NYPD officer Frank Serpico, who went undercover to expose corruption in the police force. Both Maas's book and the film cover 12 years, 1960 to 1972.[7]

| Serpico | |

|---|---|

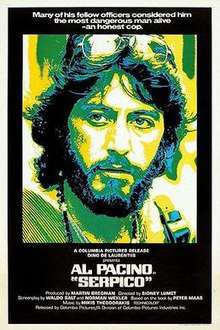

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Sidney Lumet |

| Produced by | Martin Bregman |

| Screenplay by | |

| Based on | Serpico by Peter Maas |

| Starring | Al Pacino |

| Music by | Mikis Theodorakis |

| Cinematography | Arthur J. Ornitz |

| Edited by | Dede Allen |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 130 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2.5–3 million[2] or $3.3 million[3] |

| Box office | $29.8 million (North America)[4] or $23.4 million.[3] |

The film and principals were nominated for numerous awards, earning recognition for its score, direction, screenplay, and Pacino's performance. The film was a commercial success.

Plot

In 1971, NYPD Officer Frank Serpico is rushed to the hospital, having been shot in the face. Chief Sidney Green fears Serpico may have been shot by a cop.

Years earlier, Frank graduates from the police academy and becomes frustrated with his fellow officers’ laxness. On patrol, he confronts three men raping a woman, and apprehends one of the assailants. When the suspect is beaten during interrogation, Frank declines to join in, and persuades him to give up the others. Frank breaks protocol to arrest the suspect himself, but is coerced not to take credit.

Growing out his hair and mustache, Frank finds an assignment with the Bureau of Criminal Investigation. He moves to Greenwich Village and begins dating Leslie, a woman in his Spanish class. Due to his less-than-conventional appearance and interests, such as ballet, and a misunderstanding in the men’s bathroom, he is accused of being homosexual. Frank clears up the matter with Captain McLain but requests a transfer, with hopes of being promoted to detective.

At his new precinct, Frank is allowed to keep his hair and beard, and to use his own clothes and car on patrol. While chasing a burglar, Frank is nearly shot when other officers fail to recognize him. Assigned to plainclothes duty, he befriends Bob Blair, who has been assigned to the Mayor’s Office of Investigations. Leslie leaves Frank to marry another man in Texas.

Frank is given a bribe and informs Blair, who arranges a meeting with a high-ranking investigator. Told that he must either testify – and likely be killed by corrupt cops – or “forget it”, Frank quietly turns the bribe over to his sergeant. Striking up a romance with his neighbor Laurie, he reaches out to McLain for another transfer, and begins recording his phone calls.

Reassigned to the “clean as a hound’s tooth” 7th Division, Frank immediately discovers further police corruption. Forced to accompany fellow plainclothes officers as they perpetrate violence, extortion, and collect payoffs, he refuses to accept his share of the money. He informs McLain, who assures him that the police commissioner wants him to continue gathering evidence from the inside and that Frank will be contacted by the chief's office. Frank becomes impatient waiting for the promised contact fearing for his life. Frank and Blair go to the mayor’s right-hand man, who promises a real investigation and the mayor’s support, but they are stymied by political pressure. Frank dismisses Blair’s suggestion that they go to other officials or the press.

Frank’s colleagues try again to convince him to take the payoff money, but he declines. The strain takes a toll on Frank, and his relationship with Laurie. When he discovers a suspect he arrested receiving special treatment, Frank brutalizes the man, whom he reveals served fifteen years for killing a cop.

Frustrated after a year-and-a-half of police inaction, and no word from the commissioner, Frank informs McLain that he has gone to outside agencies with his allegations. In front of the squad, Frank is sent to meet with division inspectors, who explain that his charges never made it up the chain of command. The inspectors inform the commissioner, who orders them to investigate the division themselves, and acknowledges that McLain told him of the allegations.

As the investigation proceeds, Frank is threatened by the squad, and Laurie leaves him. The DA leads Frank to believe that if he testifies in a grand jury, a major investigation into rampant department corruption will happen. He is deeply dismayed when during the grand jury he is prevented by the DA from answering questions that point up the chain of command. When Frank complains to people who keep dragging their feet about investigating and doing something about corruption, it becomes increasingly clear that their greatest fear and vulnerability is that he goes to any outside independent agency. Knowing his life is in danger, Frank goes with an honest division commander and Blair to the New York Times, making his allegations public, and is reassigned to a dangerous narcotics squad in Brooklyn, where he finds even greater corruption.

During a drug bust in 1971, Frank is shot in the face when his backup fails to act. He recovers, though with lifelong effects from his wound, and finally receives a detective’s gold shield but rejects it. He testifies before the Knapp Commission, a government inquiry into NYPD police corruption. An epilogue reveals that he resigned from the NYPD on June 15, 1972. Awarded the Medal of Honor for “conspicuous bravery in action”, he moved to Switzerland.

Cast

- Al Pacino as Frank Serpico

- John Randolph as Chief Sidney Green

- Jack Kehoe as Tom Keough

- Biff McGuire as Captain Inspector McClain

- Barbara Eda-Young as Laurie

- Cornelia Sharpe as Leslie

- Edward Grover as Inspector Lombardo

- Tony Roberts as Bob Blair

- Allan Rich as District Attorney Herman Tauber

- Albert Henderson as Peluce

- Joseph Bova as Potts

- Woodie King Jr. as Larry

- James Tolkan as Lieutenant Steiger

- Bernard Barrow as Inspector Roy Palmer

- Nathan George as Lieutenant Nate Smith

- M. Emmet Walsh as Gallagher

- F. Murray Abraham as Serpico's partner (uncredited)

- Judd Hirsch as hospital police guard (uncredited)

Production

Prior to any work on the film, producer Martin Bregman had lunch with Peter Maas to discuss a film adaptation of his biography of Frank Serpico.[8] Waldo Salt, a screenwriter, began to write the script, which director Sidney Lumet deemed to be too long.[8] Another screenwriter, Norman Wexler, did the structural work followed by play lines.[8]

Director John G. Avildsen was originally slated to direct the movie, but was removed from production due to differences with producer Bregman.[9] Lumet took the helm as director just before filming.[9]

The story was filmed in New York City. A total of 104 different locations in four of the five boroughs of the city (all except Staten Island) were used.[2] An apartment at 5-7 Minetta Street in Manhattan's Greenwich Village was used as Serpico's residence, though he lived on Perry Street during the events depicted in the film.[10] Lewisohn Stadium, which was closed at the time of filming, was used for one scene.[11]

Release

Theatrical run

The film opened at the Baronet and Forum theatres in New York City on December 5, 1973 and in Los Angeles on December 18, 1973.[1] The film went into general release on February 6, 1974, one week prior to the Academy Awards nominations.[12]

Home media

Serpico was released on VHS and is available on Region 1 DVD since 2002 and Region 1 Blu-ray since 2013.[13] The Masters of Cinema label have released the film in a Region B Blu-ray on 24 February 2014 in the United Kingdom.[13] This version contains three video documentaries about the film, as well as a photo gallery with an audio commentary by director Sidney Lumet and a 44-page booklet.[14]

Reception

Box office

Serpico opened on two screens in New York City, grossing $123,000 in its first week.[15] It was a major commercial success, given the times and its modest budget, which ranged from $2.5 million to $3 million,[2][9] grossing $29.8 million in the United States and Canada,[4] making it the 12th highest-grossing film of 1973.

Critical response

Serpico was widely acclaimed by critics.[9] At Rotten Tomatoes, it currently holds at a score of 90% "Fresh", based on reviews from 41 critics, and an average rating of 8.06/10. The site's consensus states: "An engrossing, immediate depiction of early '70s New York, Serpico is elevated by Al Pacino's ferocious performance."[16] At Metacritic, which assigns a weighted average score out of 100 to reviews from mainstream critics, the film received an average score of 87 based on seven reviews, indicating "universal acclaim." [17]

Accolades

Pacino's role as Frank Serpico is ranked at #40 on the American Film Institute's AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains list.[18] Serpico is also ranked at #84 on the AFI's AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers, a list of America's most inspiring films.[19]

The original score was composed by Mikis Theodorakis, nominated for both the Grammy Award for Best Score Soundtrack for Visual Media and the BAFTA Award for Best Film Music.[20] Sidney Lumet's direction was nominated for both the BAFTA Award for Best Direction and the Directors Guild of America.[20] The film was nominated for the Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Drama.[20]

The film also received Academy Awards nominations for Best Actor (Al Pacino) and Best Adapted Screenplay.[20] The script won the Writers Guild Award for Best Adapted Screenplay.[20]

Pacino won his first Golden Globe award for Best Actor in 1974 for his performance in the film.[20] He also received a BAFTA nomination for Best Actor in a Leading Role.[20]

Television series

A weekly television series based on Maas' book and the motion picture was broadcast on NBC between September 1976 and February 1977, with David Birney playing the role of Frank Serpico. Only 14 episodes were broadcast, with one being unaired. The series was preceded by a pilot film, Serpico: The Deadly Game, which was broadcast in April 1976.

See also

References

- Serpico at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Nixon, Rob. "Behind the Camera on SERPICO". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- Knoedelseder, William K., Jr (August 30, 1987). "De Laurentiis: Producer's Picture Darkens". Los Angeles Times. pp. 1–2.

- "Serpico (1973)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- Rybin, Steven (2013). Michael Mann: Crime Auteur. Scarecrow Press. p. 139. ISBN 0810890844.

- Silver, Alain; Ward, Elizabeth (1992). Film Noir: An Encyclopedic Reference to the American Style (3rd ed.). New York: The Overlook Press. ISBN 0-87951-479-5.

- "Serpico". TheMobMuseum.org. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- Nixon, Rob. "Serpico (1974)". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved January 28, 2016.

- "Serpico". American Film Institute. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- Kilgannon, Corey (January 22, 2010). "Serpico on Serpico". The New York Times. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- Lewisohn Stadium on YouTube

- "'Serpico' Domestic Potential Gambled on Mid-Dec. Dates". Variety. January 2, 1974. p. 4.

- "Serpico (1973): Company Credits". IMDb. Retrieved January 29, 2016.

- "Serpico". Eureka Video. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- "'Serpico,' In 2, Giant $123,000". Variety. December 12, 1973. p. 8.

- "Serpico (1973)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved December 22, 2019.

- "Serpico (re-release)". Metacritic. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- "AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains". American Film Institute. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- "AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers". American Film Institute. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- "Serpico (1973): Awards". IMDb. Retrieved January 28, 2016.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Serpico |