Prince of the City

Prince of the City is a 1981 American neo-noir[2] crime drama film co-written and directed by Sidney Lumet based on Robert Daley's 1978 book of the same name about an NYPD officer who chooses to expose police corruption for idealistic reasons. The character of Daniel Ciello, played by Treat Williams, was based on real-life NYPD Narcotics Detective Robert Leuci.[lower-alpha 1]. The large supporting cast also featured actors Jerry Orbach, Bob Balaban, and Lindsay Crouse.

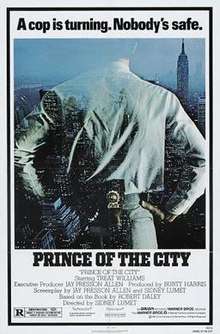

| Prince of the City | |

|---|---|

Theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | Sidney Lumet |

| Produced by | Burtt Harris |

| Screenplay by | Sidney Lumet Jay Presson Allen |

| Story by | Robert Daley (book) |

| Starring | Treat Williams Jerry Orbach Richard Foronjy Lindsay Crouse Bob Balaban |

| Music by | Paul Chihara |

| Cinematography | Andrzej Bartkowiak |

| Edited by | Jack Fitzstephens |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 167 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $8.6 million |

| Box office | $8,124,257[1] |

Prince of the City was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay, but lost to On Golden Pond.

Plot

Danny Ciello is a narcotics detective who works in the Special Investigations Unit of the New York City Police Department. He and his partners are called "Princes of the City" because they are largely unsupervised and are given wide latitude to make cases against defendants. They are involved in numerous illegal practices, such as skimming money from criminals and supplying informants with drugs.

Danny himself has a drug addict for a brother and a cousin in organized crime. After an incident in which Danny beats up a junkie to supply another junkie with heroin, his conscience begins to bother him. He is approached by internal affairs and federal prosecutors to participate in an investigation of police corruption. In exchange for potentially avoiding prosecution as well as federal protection for himself, his wife, and his children, Ciello wears a wire and works undercover to expose the inner workings of illegal police activity and corruption. He agrees to cooperate as long as he does not have to turn in his partners, but his past misdeeds and criminal associates come back to haunt him.

One of his partners commits suicide during interrogation, and his cousin in the mafia, who saves his life on one occasion and warns him of a contract on his life at another point, winds up dead. While confessing three crimes he committed in the 11 years he worked for the SIU, Danny perjures himself by denying the many other offenses he and his partners have committed. Despite repeated professions of loyalty, he finally gives up all of his partners, one of whom shoots himself as a result of this betrayal. Most of the others turn against him. In the end, the chief government prosecutor decides not to prosecute Ciello and he returns to work as an instructor at the police academy.[3]

Cast

- Treat Williams ... Daniel Ciello

- Jerry Orbach ... Gus Levy

- Richard Foronjy ... Joe Marinaro

- Don Billett ... Bill Mayo

- Kenny Marino ... Dom Bando

- Carmine Caridi ... Gino Mascone

- Tony Page ... Raf Alvarez

- Norman Parker ... Rick Cappalino

- Paul Roebling ... Brooks Paige

- Bob Balaban ... Santimassino

- James Tolkan ... District Attorney Polito

- Steve Inwood ... Mario Vincente

- Lindsay Crouse ... Carla Ciello

- Matthew Laurance ... Ronnie Ciello

- Tony Turco ... Socks Ciello

- Ronald Maccone ... Nick Napoli (as Ron Maccone)

- Ron Karabatsos ... Dave DeBennedeto

- Tony DiBenedetto ... Carl Alagretti

- Tony Munafo ... Rocky Gazzo

- Robert Christian ... The King

- Lee Richardson ... Sam Heinsdorff

- Lane Smith ... Tug Barnes

- Cosmo Allegretti ... Marcel Sardino

- Bobby Alto ... Mr. Kanter

- Michael Beckett ... Michael Blomberg

- Burton Collins ... Monty

- Henry Ferrentino ... Older Virginia Guard

- Carmine Foresta ... Ernie Fallacci

- Conard Fowkes ... Elroy Pendleton

- Peter Friedman ... D.A. Goldman

- Peter Michael Goetz ... Attorney Charles Deluth

- Lance Henriksen ... D.A. Burano

- Eddie Jones ... Ned Chippy

- Don Leslie ... D.A. D'Amato

- Dana Lorge ... Ann Mascone

- Harry Madsen ... Bubba Harris

- E.D. Miller ... Sergeant Edelman

- Cynthia Nixon ... Jeannie

- Ron Perkins ... Virginia Trooper

- Lionel Pina ... Sancho

- José Angel Santana ... José (as José Santana)

- Walter Brooke ... Judge (uncredited)

- Alan King ... Himself (uncredited)

- Bruce Willis ... Extra (uncredited)[4]

- Ilana Rapp ... Beach Player (uncredited)

Production

When producer and screenwriter Jay Presson Allen read Robert Daley's book, Prince of the City (1978), she was convinced it was an ideal Sidney Lumet project, but the film rights had already been sold to Orion Pictures for Brian De Palma and David Rabe. Allen let it be known that if that deal should fall through, then she wanted the picture for Lumet. Just as Lumet was about to sign for a different picture, they got the call that Prince of the City was theirs.

Allen hadn't wanted to write Prince of the City, just produce it. She was put off by the book's non-linear story structure, but Lumet wouldn't make the picture without her, and agreed to write the outline for her. Lumet and Allen went over the book and agreed on what they could use and what they could do without. To her horror, Lumet would come in every day for weeks and scribble on legal pads. She was terrified that she would have to tell him that his stuff was unusable, but to her delight the outline was wonderful and she went to work.[5] It was her first project with living subjects, and Allen interviewed nearly everyone in the book and had endless hours of Bob Leuci’s tapes for back-up. With all her research and Lumet's outline, she eventually turned out a 365-page script in 10 days. It was nearly impossible to sell the studio on a three-hour picture, but by offering to slash the budget to $10 million they agreed. (When asked if the original author ever has anything to say about how their book is treated, Allen replied: "Not if I can help it. You cannot open that can of worms. You sell your book, you go to the bank, you shut up.")[6]

Supposedly, Bruce Willis has a role as a background actor in this film, and Treat Williams tipped him off about The Verdict.[7]

Orion Pictures had bought Daley's book for $500,000 in 1978.[8] Daley was a former New York Deputy Police Commissioner for Public Affairs who wrote about Robert Leuci, an NYPD detective whose testimony and secret tape recordings helped indict 52 members of the Special Investigation Unit and convict them of income tax evasion.[8] Originally, Brian De Palma was going to direct with David Rabe adapting the book[9] and Robert De Niro playing Leuci but the project fell through.[10] Sidney Lumet came aboard to direct under two conditions: he did not want a big name movie star playing Leuci because he did not "want to spend two reels getting over past associations,"[10] and the movie's running time would be at least three hours long.[9]

Lumet cast Treat Williams after spending three weeks talking to him and listening to the actor read the script and then reading it again with 50 other cast members.[11] In order to research the role, the actor spent a month learning about police work, hung out at 23rd Precinct in New York City, went on a drug bust and lived with Leuci for some time.[12] By the time rehearsals started, Williams said, "I was thinking like a cop."[12]

Lumet felt guilty about the two-dimensional way he had treated cops in the 1973 film Serpico and said that Prince of the City was his way to rectify this depiction.[11] He and Jay Presson Allen wrote a 240-page script in 30 days.[9] The film was budgeted at $10 million but the director was able to bring it in for under $8.6 million.[11]

Distribution

Orion decided to open the film initially in select theaters in order to allow good reviews and word-of-mouth to build.[8] They were unable to buy television advertising because of the cost and relied heavily on print ads, including an unusual three-page spread in the New York Times.[8]

Reception

Response from subjects

The film was considered authentic enough by the head of the Drug Enforcement Administration that he called Lumet for a copy of the movie for the DEA training program. Some law enforcement officials, however, criticized the film for glamorizing Leuci and other corrupt detectives while portraying most of the prosecutors who uncovered the crimes negatively.[13] John Guido, Chief of Inspectional Services said, "The corrupt guys are the only good guys in the film."[13]

Nicholas Scoppetta, the Special Prosecutor who helped convince Leuci to go undercover against his fellow officers, said, "In the film, it seems to be the prosecutors who are disregarding the issue of where real justice lies and the prosecutors seem to be as bad or worse than the corrupt police."[13] In fact, only two of the five prosecutors the film focuses on were portrayed negatively. In particular District Attorney Polito, played by James Tolkan, is shown as petty and vindictive. The character is based on Thomas Puccio, the assistant United States Attorney in charge of the Federal Organized Crime Strike Force in Brooklyn, and Robert Daley agrees that he was treated unfairly in the screenplay.

One of the prosecutors who befriended the Ciello character and is shown in a very positive light was based on then rookie federal prosecutor Rudolph Giuliani. The character, Mario Vincente, played by Steve Inwood, is portrayed as threatening to resign if the U.S. Attorney's office indicts Ciello (Leuci) for past transgressions. In general, the prosecutors who argued against the prosecution of Leuci are treated sympathetically, while those who sought his indictment are shown as officious and vindictive.

Critical reception

The initial release of Prince of the City garnered both positive and negative reviews, some of the latter complaining of what was considered its excessive length, or comparing Treat Williams' performance unfavorably with that of Al Pacino in Serpico, Lumet's previous film about police corruption. As of April 4, 2018, Prince of the City holds a 91% approval rating on the review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, based on 23 reviews with an average rating of 7.4/10.[14]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times called it "a very good movie and, like some of its characters, it wants to break your heart. Maybe it will."[15] Janet Maslin of the New York Times praised its "sharply detailed landscape" and states that its "brief characterizations are so keenly drawn that dozens of them stand out with the forcefulness of major performances." She concludes that it "begins with the strength and confidence of a great film, and ends merely as a good one. The achievement isn't what it first promises to be, but it's exciting and impressive all the same."[16]

The film was not commercially successful in its theatrical release, earning only $8.1 million of its $8.6 million cost.

Honors

- Nominated Best Adapted Screenplay Academy Award (Jay Presson Allen, Sidney Lumet)

- Nominated Best Director (Sidney Lumet), Best Picture, Best Actor (Treat Williams) Golden Globe Awards

- Nominated Best Picture, Edgar Allan Poe Awards

- Winner Best Director (Sidney Lumet), Kansas City Film Critics Circle

- Selected Top Ten Films of the Year, National Board of Review

- Nominated Best Supporting Actor (Jerry Orbach), National Society of Film Critics

- Winner Best Director (Sidney Lumet), New York Film Critics Circle

- Nominated Best Film, Best Screenplay (Jay Presson Allen, Sidney Lumet), Best Supporting Actor (Jerry Orbach), New York Film Critics Circle

- Winner Best Film, Venice Film Festival

- Nominated Best Adapted Screenplay (Jay Presson Allen, Sidney Lumet), Writers Guild of America

Behind the Scenes

- Partially filmed at Regis High School in NYC.

References

Citations

- Prince of the City at Box Office Mojo

- Silver, Alain; Ward, Elizabeth; eds. (1992). Film Noir: An Encyclopedic Reference to the American Style (3rd ed.). Woodstock, New York: The Overlook Press. ISBN 0-87951-479-5

- Santos, Steven (15 August 2011). "DEEP FOCUS: Sidney Lumet's PRINCE OF THE CITY (1981)". IndieWire. Penske Business Media. Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- Thomson, David (2010-11-04). The New Biographical Dictionary of Film 5Th ed. ISBN 9780748108503.

- McGilligan, Patrick (1986). Backstory : interviews with screenwriters of Hollywood's golden age. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-05666-3. OCLC 12974850.

- Crist, Judith (1984). Take 22 : Moviemakers on Moviemaking. Sealy, Shirley. New York, NY, USA: Viking. pp. 282–311. ISBN 0-670-49185-3. OCLC 10878065.

- Speed, F. Maurice; Cameron-Wilson, James (1988). "Film review. 1988-9 : including video releases". London: Columbus Books. p. 137. OCLC 153629495. Retrieved September 14, 2017.

- Harmetz, Aljean (July 18, 1981). "How Prince of the City is being "platformed"". The New York Times. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- Ansen, David (August 24, 1981). "New York's Finest". Newsweek.

- Corry, John (August 9, 1981). "'Prince of the City' Explores a Cop's Anguish". The New York Times. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- Scott, Jay (August 19, 1981). "Director Sidney Lumet Fears for the Future of "Real" Films". The Globe and Mail.

- Lawson, Carol (August 18, 1981). "Treat Williams: For the moment, Prince of the City". The New York Times. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- Raab, Selwyn (August 30, 1981). "Movie criticized as glamorizing police corruption". New York Times. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- "Prince of the City (1981)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on 30 November 2004. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- Ebert, Roger (January 1, 1981). "Prince of the City". RogerEbert.com. Ebert Digital LLC. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- Maslin, Janet (August 19, 1981). "Movie Review - LUMET'S 'PRINCE OF THE CITY'". The New York Times. Retrieved September 14, 2017.

Other sources

- Prince of the City: The Real Story (2006), 30-minute featurette on the main film's DVD

Notes

- After he quit the job, Leuci turned novelist and wrote the gritty police dramas Snitch, Odessa Beach and Captain Butterfly.