Septo-optic dysplasia

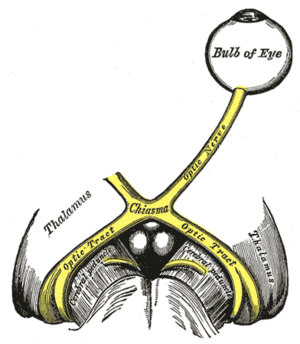

Septo-optic dysplasia (SOD), previously known as de Morsier syndrome, is a rare congenital malformation syndrome featuring underdevelopment of the optic nerve, pituitary gland dysfunction, and absence of the septum pellucidum (a midline part of the brain). Two of these features need to be present for a clinical diagnosis — only 30% of patients have all three.[3] French doctor Georges de Morsier first recognized the relation of a rudimentary or absent septum pellucidum with hypoplasia of the optic nerves and chiasm in 1956.[4]

| Septo-optic dysplasia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | de Morsier syndrome[1][2] |

| |

| The optic nerve is underdeveloped in this condition | |

| Specialty | Ophthalmology |

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms of SOD can be divided into those related to optic nerve underdevelopment, pituitary hormone abnormalities, or mid-line brain abnormalities. Symptoms may vary greatly in their severity.[5]

Optic nerve underdevelopment

About one quarter of people with SOD have significant visual impairment in one or both eyes, as a result of optic nerve underdevelopment. There may also be nystagmus (involuntary eye movements, often side-to-side) or other eye abnormalities.[5]

Pituitary hormone abnormalities

Underdevelopment of the pituitary gland in SOD leads to hypopituitarism, most commonly in the form of growth hormone deficiency.[5]

Mid-line brain abnormalities

In SOD mid-line brain structures, such as the corpus callosum and the septum pellucidum may fail to develop normally, leading to neurological problems such as seizures or development delay[6]

Causes

SOD results from an abnormality in the development of the embryonic forebrain at 4-6 weeks of pregnancy.[5] There is no known single cause of SOD, but it is thought that both genetic and environmental factors may be involved.[6]

Genetic

Rare familial recurrence has been reported, suggesting at least one genetic form (HESX1).[7] In addition to HESX1, mutations in OTX2, SOX2 and PAX6 have been implicated in SOD.[6] Genetic abnormalities are identified in fewer than one per cent of patients.[5]

Environmental

There have been suggestions that the use of drugs or alcohol during pregnancy may increase the risk of SOD.[5]

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of SOD is made when at least two of the following triad are present: optic nerve underdevelopment; pituitary hormone abnormalities; or mid-line brain abnormalities. Diagnosis is usually made at birth or during childhood, and a clinical diagnosis can be confirmed by MRI scans.[5]

Treatment

There is no cure for SOD. Pituitary insufficiency can be treated with hormones.[5]

Epidemiology

A European survey put the prevalence of SOD at somewhere in the region of 1.9 to 2.5 per 100,000 live births, with the United Kingdom having a particularly high rate and with increased risk for younger mothers.[8]

History

In 1941 Dr David Reeves at the Children's Hospital Los Angeles described an association between underdevelopment of the optic nerve with an absent septum pellucidum. Fifteen years later French doctor Georges de Morsier reported his theory that the two abnormalities were connected and coined the term septo-optic dysplasia. In 1970 American doctor William Hoyt made the connection between the three features of SOD and named the syndrome after de Morsier.[9]

References

- synd/2548 at Who Named It?

- G. de Morsier. Études sur les dysraphies, crânioencéphaliques. III. Agénésie du septum palludicum avec malformation du tractus optique. La dysplasie septo-optique. Schweizer Archiv für Neurologie und Psychiatrie, Zurich, 1956, 77: 267-292.

- Gleason, CA; Devascar, S (5 October 2011). "Congenital malformations of the Central Nervous System". Avery's Diseases of the Newborn (9 ed.). Saunders. p. 857. ISBN 978-1437701340.

- Daroff, Robert B.; Jankovic, Joseph; Mazziotta, John C.; Pomeroy, Scott L. (2015-10-25). Bradley's neurology in clinical practice (Seventh ed.). London. ISBN 9780323339162. OCLC 932031625.

- Webb, E; Dattani, M (2010). "Septo-optic dysplasia". European Journal of Human Genetics. 18: 393–397. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2009.125. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- "OMIM". Genetics Home Reference - Septo-Optic Dysplasia. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- Dattani MT, Martinez-Barbera JP, Thomas PQ, et al. (1998). "Mutations in the homeobox gene HESX1/Hesx1 associated with septo-optic dysplasia in human and mouse". Nat. Genet. 19 (2): 125–33. doi:10.1038/477. PMID 9620767.

- Garne, E; et al. (September 2018). "Epidemiology of septo-optic dysplasia with focus on prevalence and maternal age – A EUROCAT study". European Journal of Medical Genetics. 61 (9): 483–488. doi:10.1016/j.ejmg.2018.05.010.

- Borchert, Mark (2012). "Reappraisal of the Optic Nerve Hypoplasia Syndrome" (PDF). Journal of Neuro-Opthalmology. 32: 58–67.

External links

| Classification |

|---|