Semna (Nubia)

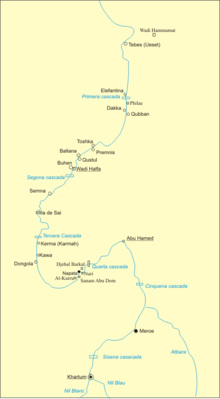

The region of Semna is 15 miles south of Wadi Halfa and is situated where rocks cross the Nile narrowing its flow—the Semna Cataract.[1][2]

Semna was a fortified area established in the reign of Senusret I (1965–1920 BC) on the west bank of the Nile at the southern end of a series of Middle Kingdom fortresses founded during the Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt (1985–1795 BC) in the Second-Cataract area of Lower Nubia. There are three forts at Semna: Semna West (Semna Gharb), Semna East (Semna Sherq, also called Kummeh or Kumma), and Semna South (Semna Gubli).[3] The forts to the east and west of the Semna Cataract are Semna East and West, respectively; Semna South is approximately one kilometer south of Semna West on the west bank of the Nile.[3][4]

The Semna gorge, at the southern edge of ancient Egypt, was the narrowest part of the Nile valley. It was here, at this strategic location, that the 12th Dynasty pharaohs built a cluster of four mud-brick fortresses: Semna, Kumma, Semna South and Uronarti — all covered by the waters of Lake Nasser since the completion of the Aswan Dam in 1971.

Archaeology of Semna

The rectangular Kumma fortress, the L-shaped Semna fortress (on the opposite bank) and the smaller square fortress of Semna South were each investigated by the American archaeologist George Reisner in 1924 and 1928. Semna and Kumma also included the remains of temples, houses and cemeteries dating to the New Kingdom (1550-1069 BC), which would have been roughly contemporary with such lower Nubian towns as Amara West and Sesebisudla, when the second cataract region had become part of an Egyptian 'empire', rather than simply a frontier zone.

The fort had several advanced features – the mudbrick walls were reinforced with logs, there were doubly fortified gates, there was a fortified corridor down to the Nile allowing ready access to water supplies. The logs increased the vulnerability to fire and traces of fires can be seen in the walls.

Semna South Fort

As a 12th Dynasty fort, Semna South is one of 17 Middle Kingdom Egyptian forts in Nubia built for the purpose of controlling trade traffic along the Nile. The Egyptian state placed great importance on control of Nubia and its goods. As Reisner (1929) notes, “the southern products, the ebony, the ivory, the pelts, the incense and resin, the ostrich feathers, the black slaves, were as much desired by the kings of the Middle Kingdom as by their forebears”.[5] Thus, forts were built along the Nile to protect the waterway from nomadic tribes and to facilitate the flow of Nubian goods into Egypt.[6][3]

Forts surrounding Semna South were excavated by the Joint Egyptian Expedition of Harvard University and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts in the 1920s,[3] but Semna South was not formally excavated until the late 1950s. The initial excavation of the fort was directed by Jean Vercoutter and Sayed Thabit Hassan Thabit with the Sudan Antiquities Service in 1956-1957.[2] Further excavations of the fort and an adjacent cemetery were conducted by the Oriental Institute Expedition to Sudanese Nubia, under the direction of Dr. Louis Vico Žabkar, in 1966-1968.[7] Today, the human remains from Semna South are curated at Arizona State University and the archaeological artifacts are curated at the University of Chicago Oriental Institute.[8](H. McDonald, personal communication, October 22, 2012).

Site Geology and Geography

Semna South is located in the Batn-El-Hajar (“Belly of the Rock”) region of Nubia between the second and third cataracts. As its name implies, the Batn-El-Hajar is “characterized by ‘bare granite ridges and gullies’, a narrowed Nile run, and heavy deposits of wind-blown sand".[9][10] Semna is situated above a geological formation known as the Basement Complex; this complex is a deposit of Precambrian sedimentary rock and later igneous rock. There is only a thin layer of fertile alluvial soil overlying this complex which results in poor agricultural potential.[9]

Archaeological Excavations of Semna South

While the fort at Semna South was described by Reisner (1929), it was not formally excavated until 1956-1957 by the Sudan Antiquities Service under the direction of Jean Vercoutter and Sayed Thabit Hassan Thabit.[2] This excavation explored the majority (four-fifths) of the fort and “made a limited trial digging” in the adjacent Meroitic cemetery.[4]

Vercoutter (1966) notes that their work was preliminary and by no means complete. He encouraged further investigation of the site: “it seems of the utmost importance for the history of the site that new excavations are undertaken at Semna South before its flooding under the waters of the new Aswan Dam”.[11] Beginning in 1966 the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago continued excavating where Vercoutter and colleagues had ended.

Between 1966 and 1968 the University of Chicago Oriental Institute Expedition to Sudanese Nubia excavated the remainder of the Semna South fort and the adjacent cemetery. Detailed excavations were conducted of the fort walls, a church, a dump site, and the cemetery.[7] To the author’s knowledge, this was the final archaeological excavation conducted at Semna South.

Results and Significance of the Excavations

Results from the 1950s

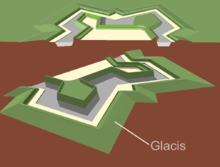

During the 1956-1957 field season, Vercoutter and colleagues were able to interpret the building plan of the fort. The building is composed of the following features: a glacis, outer girdle wall, an inner ditch, a main wall, and an open inner space.[12] They concluded that the fort was never inhabited permanently; rather, it was occupied for limited periods of time by men of the garrison coming from the fort at Semna West.

They found little evidence of Middle Kingdom occupation, but did discover ruins of a Christian settlement at Semna South. The Christian settlement was not fully excavated by the Sudan Antiquities Service expedition, but they did note that the houses had been reconstructed by the Christian inhabitants and that they had built a new stone girdle wall around the west side of the fort.[13] They concluded that the Christian settlement had been inhabited by a fairly poor community.

Results from the 1960s

Architectural Findings

.jpg)

The 1966-1968 excavations at Semna South determined, contrary to Vercoutter, that the fort was permanently occupied from the reign of Senusret I to the first few years of reign of Amenemhat III of the 12th Dynasty.[14][15] Excavations of the church, sometimes called the “Sheik’s tomb,” revealed that only a portion of the original structure still remained.[16] As of 1982 when Žabkar and Žabkar published their report, they were not able to date the church due to the paucity of pottery within the church or nearby. However, they did provide a hypothetical estimate: “the church in its final, that is apsidal, form would date to the classic Christian period in Nubia, somewhere between the ninth and the first part of the eleventh century A.D.".[16]

This expedition unearthed a great wall which connected the forts at Semna South and Semna West. This wall strengthened the view that the military fortifications in the Semna region were built by the Egyptians in response to the “strong pressures and infiltration attempts on the part of southerners during the 12th Dynasty, allusions to which are found in the well-known Semna Stela and Semna Dispatches”.[17] Žabkar and Žabkar (1982) speculate that perhaps there was a complex of fortifications which embraced Semna South and West, and perhaps other forts in the region, but there is no definitive evidence for such a complex.

Artifactual Findings

An area located on the fort’s north-west side previously called a ‘graveyard,’ ‘occupation site,’ or an ‘encampment,’ and covered in pot sherds was also excavated during the 1966–1968 field seasons. Upon excavation, it was revealed to be a 12th Dynasty dump site, and was “the most significant [find] for the study of the history of the Semna South fort, particularly for the study of its communications with the other forts of the first and second cataract regions”.[18] The dump site was a series of holes which were initially clay quarries and later utilized as a dumping place for discarded fort objects. Some of the holes were deep and some were shallow; the two deepest were K-1 and K-4.[19][7] Within these holes, the discarded objects and pottery sherds were mixed into a loose mass of debris with no discernible stratigraphic layers.

The finds within these holes are of great significance. The first is a well-preserved 12th Dynasty axe, which according to Žabkar and Žabkar (1982), is a rare occurrence in Sudanese and Egyptian Nubia.[20] Second, pottery sherds of the C-Group type (indigenous Nubian inhabitants from ca. 2000 – 1500 BC) were found which suggests a peaceful coexistence between the C-Group individuals and the Egyptians.[19][6][21] Third, and most importantly, were seal impressions on numerous pieces of pottery. The most significant seals are those which bore the name of the fort, which until this discovery was only partially known.[19]

Prior to this seal being found, the Egyptian name of the fort at Semna South was written in hieratic as “Repressing the…” on a fragmentary piece of papyrus discovered in 1896 by James Quibell near the Ramesseum.[19][3] After studying these seals, Dr. Žabkar translated the hieroglyphics as “Subduer of the Setiu-Nubians” or “Subduer of the Seti-land”.[19][10] This find is important because it officially confirms the Egyptian name of the fort at Semna South and clarifies the fragmentary name written on the Ramesseum papyrus. Additionally it signifies the role of Egypt in Nubia: ruler.

Bioarchaeological Findings

The Oriental Institute Expedition also excavated the large cemetery to the north of the fort. This cemetery contained approximately 560 graves—representing over 800 individuals—of which about 494 were from the Meroitic period (4th century BC – 4th century AD), 50 from the X-Group period (4th – 6th century AD), and 16 from the Christian period (550 – 1500 AD).[22][23] The Meroitic period through the Christian period is a span of approximately 2,000 years, which indicates that the fort was used for an extended period of time during Egyptian and Nubian history.

The Meroitic graves were oriented east to west and were of several styles: rectangular pit graves with superstructures resembling mastabas, oblong pits without superstructures, and rectangular pits with mud-brick burial vaults.[7] For those remains found in situ, the heads were oriented to the west and the bodies were extended on their backs with hands over the pelvis.[22] Numerous artifacts were found within the Meroitic graves: black and brown wear pottery; copper and bronze bowls; a finely carved wooden bowl; a glass ointment jar; bronze mirrors; copper, iron, and bronze jewelry; beads and pendants; hunting equipment; leather; and fragments of shrouds.[24]

The graves of the X-Group were oriented north to south and most were deep pits with a lateral chamber.[7] Most of the graves, according to Žabkar and Žabkar (1982), “had a shelf, composed of earth, mud-brick, or stones, running alongside the chamber, which supported the blocking material”.[25] For the remains found in situ, the bodies were in a flexed position on their sides with the heads facing towards the north, northwest, or south. In most cases a burial shroud was present, although it was often fragmentary.[25] Objects recovered from these graves are as follows: red ware pottery; jewelry; personal grooming tools; hunting equipment; leather sandals; and clothing.[26]

The Christian period graves were oriented east to west and most were deep, narrow, oblong shaft tombs.[26] Only one grave had a superstructure. Of the remains in situ, the bodies were usually extended and supine with the hands over the pelvis with the heads oriented towards the west. One body was found on its side in a flexed position facing north.[26] Most of the bodies were wrapped in a linen or wool shroud which had been secured by a chord.[26]

Additional Analysis of Semna South Material

The human remains recovered from Semna South have been studied by numerous anthropologists and other specialists. Hrdy (1978) analyzed hair samples from Semna South mummies. He concluded that the hair color of these individuals was lighter than previously thought in ancient Nubia and the hair of the X-Group males was curlier than the Meroitic males.[27] In 1993, Arriaza, Merbs, and Rothschild published a study evaluating the prevalence of a pathological condition known as diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH). They found that approximately 13% of the individuals from the Meroitic cemetery were afflicted with this condition and that it was more common among males.[28] Alvrus (1999) assessed the skeletal fracture patterns for almost 600 individuals from the Semna South site. She analyzed healed fractures of the skull and appendicular skeleton and found that almost 21% of adults had at least one healed fracture and that the skull was the most frequently injured region of the body. She attributes much of the trauma to the rocky physical environment, but also notes that craniofacial trauma may be the result of interpersonal violence.[29]

Dissertations and theses which used the Semna South remains are numerous. They include topics such as the sexual dimorphism of dental pathology,[30] the presence of schistosomiasis in ancient Nubia,[31] non-metric biological distance analysis,[32] and a craniometric analysis.[33]

Conclusions

Excavated between 1956–57 and 1966–68, Semna South is a 12th Dynasty fort located in Nubia—the present Republic of Sudan—on the west bank of the Nile. These excavations revealed the building plan of the fort, a church, a cemetery, and numerous other settlement-related features. Some of the most important discoveries were found within dumps near the fort. In particular, Žabkar recovered pottery seals which provided the Egyptian name of the fort (“Subduer of the Setiu-Nubians” or “Subduer of the Seti-land”) which was unknown until the 1966-1968 field seasons.[19][10]

The artifacts recovered from these excavations, including pottery sherds, textiles, jewelry, an axe, and additional seals, indicate that the fort at Semna South was utilized during the Middle Kingdom. The adjacent cemetery with burials from the Meroitic, X-Group, and Christian periods suggests a much longer habitation of the region: from the Middle Kingdom until the Middle Ages.

Archaeological excavations of Semna South have contributed to the overall understanding of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt fort system. These forts established military control over Upper and Lower Nubia and the Nile river transport of commodities, and were integral parts of the Egyptian empire.

The temples of Dedwen and Sesostris III were moved to the National Museum of Sudan in Khartoum prior to the flooding of Lake Nasser.

References

- Arriaza, Merbs & Rotschild 1993.

- Vercoutter 1966.

- Reisner 1929.

- Vercoutter 1966, p. 125.

- Reisner 1929, p. 66.

- Bard 2008.

- Žabkar & Žabkar 1982.

- Arriaza, merbs & Rotschild 1993.

- Alvrus 1999, p. 418.

- Žabkar 1975.

- Vercoutter 1966, p. 131.

- Vercoutter 1966, p. 127.

- Vercoutter 1966, p. 130.

- Žabkar & Žabkar 1982, p. 15.

- Bard 2008, p. 42.

- Žabkar & Žabkar 1982, p. 12.

- Žabkar & Žabkar 1982, p. 13.

- Žabkar 1972, p. 83.

- Žabkar 1972.

- Žabkar & Žabkar 1982, p. 16.

- Beckett & Lowell 1994.

- Žabkar & Žabkar 1982, p. 21.

- Welsby 2002, p. 13.

- Žabkar & Žabkar 1982, pp. 21-22.

- Žabkar & Žabkar 1982, p. 22.

- Žabkar & Žabkar 1982, p. 23.

- Hrdy 1978, p. 277.

- Arriaza, merbs & Rotschild 1993, p. 243.

- Alvrus 1999, p. 417.

- Burns 1982.

- Alvrus 2006.

- Moore 1996.

- Sandy-Karkoutli 1989.

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Semna. |

- Alvrus, A. (1999). "Fracture patterns among the Nubians of Semna South, Sudanese Nubia". International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. 9: 417–429. doi:10.1002/(sici)1099-1212(199911/12)9:6<417::aid-oa509>3.0.co;2-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Alvrus, A. (2006). The conqueror worm: Schistosomiasis in ancient Nubia (Ph.D.).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Retrieved from ProQuest. (3210094)

- Arriaza, B.T.; Merbs, C.F.; Rothschild, B.M. (1993). "Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis in Meroitic Nubians from Semna South, Sudan". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 92: 243–248. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330920302.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bard, K.A. (2008). An introduction to the archaeology of ancient Egypt. Malden: Blackwell.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beckett, S.; Lowell, N.C. (1994). "Dental disease evidence for agricultural intensification in the Nubian C-Group". International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. 4: 223–239. doi:10.1002/oa.1390040307.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burns, P.E. (1982). A study of sexual dimorphism in the dental pathology of ancient peoples (Ph.D.).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Retrieved from ProQuest. (8216427)

- Dunham, D.; Janssen, J.M.A. (1960). Second cataract forts I: Senna, Kumma. Boston. pp. 5–112.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hrdy, D.B. (1929). "Analysis of hair samples of mummies from Semna South (Sudanese Nubia)". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 49: 277–282. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330490217.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kemp, B.J. (1989). Ancient Egypt: anatomy of a civilization. London. pp. 174–6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moore, C.M. (1996). Semna South, Sudan: A nonmetric biological distance study (M.Sc.). Arizona State University.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (unpublished).

- Reisner, G.A. (1925). "Excavation in Egypt and Ethiopia". Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts. 22: 18–28.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reisner, G.A. (1929). "Egyptian forts at Semna and Uronarti". Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts. 27: 64–75.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sandy-Karkoutli, M.L. (1989). Perspectives on the Nubians of Semna South, Sudan: A craniometric analysis (M.Sc.). Arizona State University.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (unpublished).

- Shaw, I.; Nicholson, P. The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt. p. 258.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vercoutter, J. (1966). "Semna South fort and the records of Nile levels at Kumma". Kush. 14: 125–164.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Welsby, D.A. (2002). The medieval kingdoms of Nubia: Pagans, Christians and Muslims along the Middle Nile. London: The British Museum Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wright, G.R.H. (1968). "Tell el-Yehūdīyah and the glacis". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 84: 1–17.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Žabkar, L.V. (1972). "The Egyptian name of the fortress of Semna South". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 58: 83–90. doi:10.2307/3856238.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Žabkar, L.V. (1975). "Semna South: The southern fortress". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 61: 42–44. doi:10.2307/3856488.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Žabkar, L.V.; Žabkar, J.J. (1975). "Semna South: A preliminary report on the 1966-68 excavations of the University of Chicago Oriental Institute Expedition to Sudanese Nubia". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 19: 7–50.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)