Dedun

Dedun (or Dedwen) was a Nubian god worshipped during ancient times in that part of Africa and attested as early as 2400 BC. There is much uncertainty about his original nature, especially since he was depicted as a lion, a role which usually was assigned to the son of another deity. Nothing is known of the earlier Nubian mythology from which this deity arose, however. The earliest known information in Egyptian writings about Dedun indicates that he already had become a god of incense by the time of the writings. Since at this historical point, incense was an extremely expensive luxury commodity and Nubia was the source of much of it, he was quite an important deity. The wealth that the trade in incense delivered to Nubia led to his being identified by them as the god of prosperity, and of wealth in particular.

He is said to have been associated with a fire that threatened to destroy the other deities, however, leading many Nubiologists to speculate that there may have been a great fire at a shared complex of temples to different deities, that started in a temple of Dedun, although there are no candidate events known for this.

Although mentioned in the Pyramid Texts of ancient Egypt as being a Nubian deity,[1] there is no evidence that Dedun was worshipped by the Egyptians, nor that he was worshipped in any location north of Swenet (contemporary Aswan), which was considered the most southerly city of Ancient Egypt. Nevertheless, in the Middle Kingdom of Egypt, during the Egyptian rule over Kush, Dedun was said by the Egyptians to be the protector of deceased Nubian rulers and their god of incense, thereby associated with funerary rites.

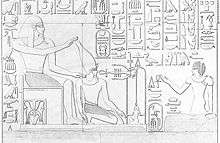

Atlanersa, a Kushite ruler of the Napatan kingdom of Nubia, is known to have started a temple dedicated to the syncretic god Osiris-Dedun[2] at Jebel Barkal.[3]

References

- Lichtheim, Miriam (1975). Ancient Egyptian Literature, vol 1. London, England: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-02899-9.

- Kendall & Ahmed Mohamed 2016, pp. 34 & 94.

- Török 2002, p. 158.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dedun. |