Self-reference

Self-reference occurs in natural or formal languages when a sentence, idea or formula refers to itself. The reference may be expressed either directly—through some intermediate sentence or formula—or by means of some encoding. In philosophy, it also refers to the ability of a subject to speak of or refer to itself, that is, to have the kind of thought expressed by the first person nominative singular pronoun "I" in English.

Self-reference is studied and has applications in mathematics, philosophy, computer programming, and linguistics. Self-referential statements are sometimes paradoxical, and can also be considered recursive.

In logic, mathematics and computing

In classical philosophy, paradoxes were created by self-referential concepts such as the omnipotence paradox of asking if it was possible for a being to exist so powerful that it could create a stone that it could not lift. The Epimenides paradox, 'All Cretans are liars' when uttered by an ancient Greek Cretan was one of the first recorded versions. Contemporary philosophy sometimes employs the same technique to demonstrate that a supposed concept is meaningless or ill-defined.[2]

In mathematics and computability theory, self-reference (also known as Impredicativity) is the key concept in proving limitations of many systems. Gödel's theorem uses it to show that no formal consistent system of mathematics can ever contain all possible mathematical truths, because it cannot prove some truths about its own structure. The halting problem equivalent, in computation theory, shows that there is always some task that a computer cannot perform, namely reasoning about itself. These proofs relate to a long tradition of mathematical paradoxes such as Russell's paradox and Berry's paradox, and ultimately to classical philosophical paradoxes.

In game theory, undefined behaviors can occur where two players must model each other's mental states and behaviors, leading to infinite regress.

In computer programming, self-reference occurs in reflection, where a program can read or modify its own instructions like any other data.[3] Numerous programming languages support reflection to some extent with varying degrees of expressiveness. Additionally, self-reference is seen in recursion (related to the mathematical recurrence relation) in functional programming, where a code structure refers back to itself during computation.[4] 'Taming' self-reference from potentially paradoxical concepts into well-behaved recursions has been one of the great successes of computer science, and is now used routinely in, for example, writing compilers using the 'meta-language' ML. Using a compiler to compile itself is known as bootstrapping. Self-modifying code is possible to write (programs which operate on themselves), both with assembler and with functional languages such as Lisp, but is generally discouraged in real-world programming. Computing hardware makes fundamental use of self-reference in flip-flops, the basic units of digital memory, which convert potentially paradoxical logical self-relations into memory by expanding their terms over time. Thinking in terms of self-reference is a pervasive part of programmer culture, with many programs and acronyms named self-referentially as a form of humor, such as GNU ('Gnu's not Unix') and PINE ('Pine is not Elm'). The GNU Hurd is named for a pair of mutually self-referential acronyms.

Tupper's self-referential formula is a mathematical curiosity which plots an image of its own formula.

In biology

The biology of self-replication is self-referential, as embodied by DNA and RNA replication mechanisms. Models of self-replication are found in Conway's Game of Life and have inspired engineering systems such as the self-replicating 3D printer RepRap .

In art

Self-reference occurs in literature and film when an author refers to his or her own work in the context of the work itself. Examples include Miguel de Cervantes' Don Quixote, Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream, The Tempest and Twelfth Night, Denis Diderot's Jacques le fataliste et son maître, Italo Calvino's If on a winter's night a traveler, many stories by Nikolai Gogol, Lost in the Funhouse by John Barth, Luigi Pirandello's Six Characters in Search of an Author, Federico Fellini's 8½ and Bryan Forbes's The L-Shaped Room. Speculative fiction writer Samuel R. Delany makes use of this in his novels Nova and Dhalgren. In the former, Katin (a space-faring novelist) is wary of a long-standing curse wherein a novelist dies before completing any given work. Nova ends mid-sentence, thus lending credence to the curse and the realization that the novelist is the author of the story; likewise, throughout Dhalgren, Delany has a protagonist simply named The Kid (or Kidd, in some sections), whose life and work are mirror images of themselves and of the novel itself. In the sci-fi spoof film Spaceballs, Director Mel Brooks includes a scene wherein the evil characters are viewing a VHS copy of their own story, which shows them watching themselves “watching themselves”, ad infinitum. Perhaps the earliest example is in Homer's Iliad, where Helen of Troy laments: "for generations still unborn/we will live in song" (appearing in the song itself).[5]

Self-reference in art is closely related to the concepts of breaking the fourth wall and meta-reference, which often involve self-reference. The short stories of Jorge Luis Borges play with self-reference and related paradoxes in many ways. Samuel Beckett's Krapp's Last Tape consists entirely of the protagonist listening to and making recordings of himself, mostly about other recordings. During the 1990s and 2000s filmic self-reference was a popular part of the rubber reality movement, notably in Charlie Kaufman's films Being John Malkovich and Adaptation, the latter pushing the concept arguably to its breaking point as it attempts to portray its own creation, in a dramatized version of the Droste effect.

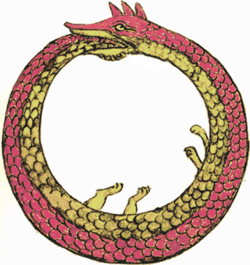

Various creation myths invoke self-reference to solve the problem of what created the creator. For example, the Egyptian creation myth has a god swallowing his own semen to create himself. The Ouroboros is a mythical dragon which eats itself.

The Quran includes numerous instances of self-referentiality.[6][7]

The surrealist painter René Magritte is famous for his self-referential works. His painting The Treachery of Images, includes the words "this is not a pipe", the truth of which depends entirely on whether the word ceci (in English, "this") refers to the pipe depicted—or to the painting or the word or sentence itself.[8] M.C. Escher's art also contains many self-referential concepts such as hands drawing themselves.

In language

A word that describes itself is called an autological word (or autonym). This generally applies to adjectives, for example sesquipedalian (i.e. "sesquipedalian" is a sesquipedalian word), but can also apply to other parts of speech, such as TLA, as a three-letter abbreviation for "three-letter abbreviation".

A sentence which inventories its own letters and punctuation marks is called an autogram.

There is a special case of meta-sentence in which the content of the sentence in the metalanguage and the content of the sentence in the object language are the same. Such a sentence is referring to itself. However some meta-sentences of this type can lead to paradoxes. "This is a sentence." can be considered to be a self-referential meta-sentence which is obviously true. However "This sentence is false" is a meta-sentence which leads to a self-referential paradox. Such sentences can lead to problems, for example, in law, where statements bringing laws into existence can contradict one another or themselves. Kurt Gödel claimed to have found such a paradox in the US constitution at his citizenship ceremony.

Self-reference occasionally occurs in the media when it is required to write about itself, for example the BBC reporting on job cuts at the BBC. Notable encyclopedias may be required to feature articles about themselves, such as Wikipedia's article on Wikipedia.

Fumblerules are a list of rules of good grammar and writing, demonstrated through sentences that violate those very rules, such as "Avoid cliches like the plague" and "Don't use no double negatives". The term was coined in a published list of such rules by William Safire.[9][10]

In popular culture

- Douglas Hofstadter's books, especially Metamagical Themas and Gödel, Escher, Bach, play with many self-referential concepts and were highly influential in bringing them into mainstream intellectual culture during the 1980s. Hofstadter's law, which specifies that "It always takes longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter's Law"[11] is an example of a self-referencing adage. Hofstadter also suggested the concept of a 'Reviews of this book', a book containing only reviews of itself, which has since been implemented using wikis and other technologies. Hofstadter's 'strange loop' metaphysics attempts to map consciousness onto self-reference, but is a minority position in philosophy of mind.

- The subgenre of "recursive science fiction" or metafiction is now so extensive that it has fostered a fan-maintained bibliography at the New England Science Fiction Association's website; some of it is about science-fiction fandom, some about science fiction and its authors.[12]

See also

- Circular reference – A series of references where the last object references the first

- Droste effect – Recursive visual effect

- Mise en abyme – A formal technique of placing a copy of an image within itself

- Fourth wall – Concept in performing arts separating performers from the audience

- List of self–referential paradoxes

- Meta-joke – Class of joke including joke templates, self-referential jokes, and jokes about jokes

- Recursion – Process of repeating items in a self-similar way

- Recursive acronym – Acronym whose expansion includes a copy of itself

- Strange loop – Cyclic structure that goes through several levels in a hierarchical system.

- this (computer programming) – In programming languages, the object or class the currently running code belongs tot

- Woozle effect – Frequent citation of previous publications that lack evidence misleads individuals, groups, and the public into thinking or believing there is evidence

- Bilingual tautological expressions – Use of more words than is necessary for clear expression

- Lucid dreaming – A dream during which the dreamer is aware that they are dreaming

References

- Soto-Andrade, Jorge; Jaramillo, Sebastian; Gutierrez, Claudio; Letelier, Juan-Carlos. "Ouroboros avatars: A mathematical exploration of Self-reference and Metabolic Closure" (PDF). MIT Press. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- Liar Paradox

- Malenfant, J.; Demers, F-N. "A Tutorial on Behavioral Reflection and its Implementation" (PDF). PARC. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- Drucker, Thomas (4 January 2008). Perspectives on the History of Mathematical Logic. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-8176-4768-1.

- Homer (1990). Iliad. Translated by Robert Fagles. Penguin Books. p. 207. ISBN 1-101-15281-8.

- Madigan, David. The Qur'ân's Self-Image. Writing and Authority in Islam's Scripture.

- Boisliveau, Anne-Sylvie. Le Coran par lui-même.

- Nöth, Winfried; Bishara, Nina (2007). Self-reference in the Media. Walter de Gruyter. p. 75. ISBN 978-3-11-019464-7.

- alt.usage.english.org's Humorous Rules for Writing

- Safire, William (4 November 1979). "On Language; The Fumblerules of Grammar". New York Times. p. SM4.

- Hofstadter, Douglas. Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid. 20th-anniversary ed., 1999, p. 152. ISBN 0-465-02656-7

- "Recursive Science Fiction" New England Science Fiction Association website, last updated 3 August 2008

Sources

- Bartlett, Steven J. [James] (Ed.) (1992). Reflexivity: A Source-book in Self-reference. Amsterdam, North-Holland. (PDF). RePub, Erasmus University

- Hofstadter, D. R. (1980). Gödel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid. New York, Vintage Books.

- Smullyan, Raymond (1994), Diagonalization and Self-Reference, Oxford Science Publications, ISBN 0-19-853450-7

- Crabtree, Jonathan J. (2016), The Lost Logic of Elementary Mathematics and the Haberdasher who Kidnapped Kaizen, Proceedings of the Mathematical Association of Victoria (MAV) Annual Conference, 53, 98-106, ISBN 978-1-876949-60-0