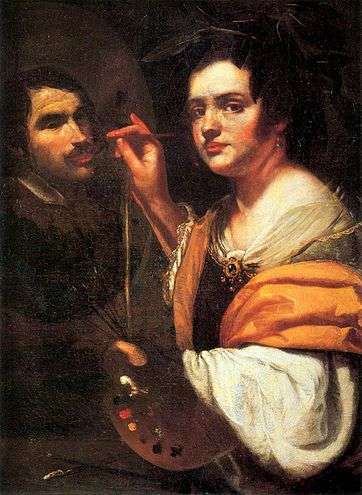

Self-Portrait (Artemisia Gentileschi)

The Self Portrait of Italian baroque artist Artemisia Gentileschi was painted in the early 1630s. It currently hangs in the Palazzo Barberini, Rome. It is one of many paintings where Gentileschi depicts herself. Beyond self-portraits, her allegorical and religious paintings often featured herself in different guises.

Attribution

The painting is generally accepted as being by Gentileschi but there have been some doubts cast. It was included in the catalogue raisonné by R. Ward Bissell,[1] but the 2001 exhibition catalogue on the Artemisia and her father Orazio considers it to be done by the workshop of Simon Vouet.[2] Later investigations have fallen firmly on the side of the painting being by Artemisia Gentileschi. In particular, Jesse M. Locker points to the similar clothing used, as well as the treatment of lace, used in other Artemisia paintings to make this decision.[3]

Quality

The painting is in a poor condition. Locker notes that it "is poorly preserved, leaving the flesh tones, particularly in the face abraded and badly deteriorated."[3]

History

There is very little detail on the provenance of the painting. The earliest is can be traced with any certainty is to 1935, when the collection of Palazzo Barberini entered the governmental Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica.[3]

Content

It is assumed that the sitter in the painting is the patron that commissioned it, but there is no evidence to support any clear identification. Artemisia's pose has led art historians to see the painting as a direct challenge to a viewer. Mary Garrard has interpreted this in the context of Artemisia's gender, i.e. a challenge to male artists of the time. This contention is made based on the shape of the painting hand, as this gesture in the 17th century represented a "challenge advanced by those confident in the strength of their abilities."[4] Locker continues the idea of the painting as a challenge, but situates it in the context of the literary and poetic culture of the times, where Gentileschi is challenging poets, "whose spoken paintings ... cannot rival her painted poems."[3]

References

- Bissell, R. Ward (1999-01-01). Artemisia Gentileschi and the authority of art: critical reading and catalogue raisonné. University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0271017872. OCLC 38010691.

- Christiansen, Keith; Mann, Judith Walker (2001). Orazio and Artemisia Gentileschi. New York; New Haven: Metropolitan Museum of Art ; Yale University Press. p. 418. ISBN 1588390063.

- Locker, Jesse M. (2015). Artemisia Gentileschi: The Language of Painting. New Haven, Yale University Press. pp. 147–57. ISBN 9780300185119.

- Garrard, Mary D. (2005). "Artemisia's Hand". In Bal, Mieke (ed.). The Artemisia Files. The University of Chicago Press. p. 28. ISBN 0226035816.