Artemisia (film)

Artemisia is a 1997 French-German-Italian biographical film about Artemisia Gentileschi, the female Italian Baroque painter.[1] The film was directed by Agnès Merlet, and stars Valentina Cervi and Michel Serrault.

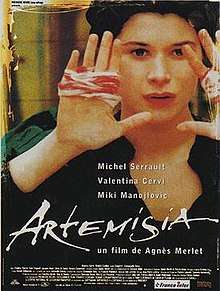

| Artemisia | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Agnès Merlet |

| Produced by | Patrice Haddad |

| Written by |

|

| Starring | |

| Music by | Krishna Levy |

| Cinematography | Benoît Delhomme |

| Edited by |

|

| Distributed by | Miramax Zoë (US) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 98 minutes |

| Country |

|

| Language | French |

Plot

Seventeen-year-old Artemisia Gentileschi (Valentina Cervi), the daughter of Orazio Gentileschi, a renowned Italian painter, exhibits her father's talent, and is encouraged by her father, who has no sons and wishes his art to survive after him. However, in the chauvinistic world of the early 17th century, Italian women are forbidden to paint human nudes or enter the Academy of Arts. Orazio allows his daughter to study in his studio, although he draws the line at letting her view nude males. She is direct and determined, and bribes the fisherman Fulvio with a kiss to let her observe his body and draw him.

Artemisia seeks the tutelage of Agostino Tassi (Mike Manojlovic), her father's collaborator in painting frescoes, to learn from him the art of perspective. Tassi is a man notorious for his night-time debauchery. The two hone their skills as artists, but they also fall in love, and begin having sexual relations. Artemisia's father discovers the couple having sexual intercourse and files a lawsuit against Tassi for rape. In the subsequent trial, Artemisia's physical state is investigated by two nuns, and then she is tortured by thumbscrews. Nevertheless, even under torture, Artemisia denies being raped, and proclaims their mutual love. Tassi himself, devastated by her plight, admits to raping her in order to stop her ordeal.

Merlet said of her film, "I didn't want to show her as a victim but like a more modern woman who took her life into her own hands."

Cast

- Valentina Cervi - Artemisia Gentileschi

- Michel Serrault - Orazio Gentileschi

- Miki Manojlović - Agostino Tassi

- Luca Zingaretti - Cosimo Quorli

- Emmanuelle Devos - Costanza

- Frédéric Pierrot - Roberto

- Brigitte Catillon - Tuzia

- Yann Trégouët - Fulvio

- Maurice Garrel - The Judge

- Liliane Rovère - The Rich Merchant's Wife

- Jacques Nolot - The Lawyer

Controversy

The film focuses on the incident of Artemisia's rape and its immediate aftermath, and was initially advertised as "a true story" by Miramax Zoe, its American distributor. However,

In the transcript (of Gentileschi's testimony at the trial, based on records preserved in an archive in Rome), Gentileschi describes the rape in graphic detail and states that Tassi continued to have sex with her... with the understanding that he would protect her honor by eventually wedding her ... In the movie, by contrast, she's a willing partner in lust. During the trial, she says only that "I love him"; "he loves me"; "he gives me pleasure." In the movie, Gentileschi refuses to testify that she was raped, even under torture, a sacrifice that prompts a devastated Tassi to make a sham confession ... Just as problematic, says Garrard, is the way the movie ascribes Gentileschi's creative maturation to the influence of, of all people, the man whom history records as her assailant ... At the same time, many inconvenient details – most glaringly, Tassi's relentless campaign during the trial to smear Gentileschi as a slut – didn't make it into the movie ...[2]

Art historian Mary Garrard and feminist Gloria Steinem, incensed by the misinformation in the film, organized a campaign to inform audiences for "Artemisia" that what they were seeing was not, as was promised in early advertisements, "The Untold True Story of an Extraordinary Woman.". They put up a website attacking the film as untruthful in presenting what they say was Artemisia's rape by her teacher, Agostino Tassi. At the New York premiere screening of the film on April 28, Gloria Steinem and other women in the audience circulated a fact sheet prepared by Steinem and Garrard.[3] This intervention led Miramax to retract its claim that that film presents a "true" story. Steinem and Garrard's intention was not to interfere with the filmmaker's creative freedom, nor with Miramax's distribution of the film, but rather to counter its historical distortions with concrete factual information about the subject.[4]

The other side

Feminist Germaine Greer points out in her chapter on Artemisia in her book on women painters, The Obstacle Race, that the rape trial transcripts are not transparent, and that there is evidence that supports Merlet's construction. The rape trial records may be found in an appendix to Garrard's book. Garrard interprets them one way (Artemisia was raped, didn't love Tassi); Greer interprets them differently (Artemisia was raped, but came to love her rapist); Merlet offers a third interpretation (Artemisia loved her rapist from the start). Garrard's account was savaged by a number of feminist reviewers, and most recently challenged by Griselda Pollock in Differencing the Canon:

Merlet's film is, I would argue, not really a biography, for there is no analysis of the impact of the early death of the artist's mother and her bereavement, no exploration of how she made a massively successful career in Italy and beyond after the horrors of the trial and her torture, how she married and mothered several daughters who also became artists, how she negotiated with some of the major patrons of her time for the commissions on which she lived and through which she, not their father, accumulated dowries for her daughter. No one wants to tell that story [5]

For sake of historical clarity, Artemisia had only one daughter.

Critical receptions

New York Times film critic Stephen Holden is very favourable of the film:

This handsomely photographed film, whose indoor scenes recreate the heavy chiaroscuro of Caravaggio paintings, takes a decidedly 90s view of a woman whom feminist art historians rescued from obscurity in the 1970s. If the central character emerges as a feminist heroine for flouting patriarchical taboos, she also happens to be a tantalizing sex kitten whose artistic curiosity smacks of voyeurism. As portrayed by Valentina Cervi, Artemisia is two distinctly different entities. One is a gorgeous early-17th-century Lolita. The other is a fearlessly ambitious teen-age prodigy who is so sure of her talent that she breaks the rules of female decorum and dares go where no nice woman of her time and station has gone before. These two Artemisias don't really fit together, but they make for a ripely sensuous portrait of the artist as a saucy but virtuous siren.[6]

Roger Ebert also liked the film:

Artemisia is as much about art as about sex, and it contains a lot of information about techniques, including the revolutionary idea of moving the easel outside and painting from nature. It lacks, however, detailed scenes showing drawings in the act of being created (for that you need La Belle Noiseuse, Jacques Rivette's 1991 movie that peers intimately over the shoulder of an artist in love). And it doesn't show a lot of Artemisia's work. What it does show is the gift of Valentina Cervi, who is another of those modern European actresses, like Juliette Binoche, Irene Jacob, Emmanuelle Beart and Julie Delpy, whose intelligence, despite everything else, is the most attractive thing about her.[7]

Daphne Merkin wrote in the New Yorker:

This controversial and confused new film, written and directed by Agnès Merlet, is ostensibly about the seventeenth-century painter Artemisia Gentileschi, but it is really the silliest form of late-twentieth-century iconography. The movie, which stars the fetching Valentina Cervi, makes a sexy love story out of Artemisia's relationship with her teacher, Agostino Tassi (played by Miki Manojlovic): it's art lessons as foreplay. "Let yourself go," Tassi tells his young pupil, as though he is quoting from Masters and Johnson, and Artemisia not only expertly guides him in bed but insists that he gave her pleasure when he raped her. Although the real Artemisia did flout the conventions of her time by insisting on painting from live models, it's hard to believe that she proceeded with the air of defiant entitlement she's given here. Once you accept the film on its own fraudulent terms, however, it's quite engaging-not least because of the erotic subtext.[8]

References

- "ARTEMISIA". Film Journal International. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- Alyssa Katz, SALON, May 15, 1998 Archived December 1, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-01-22. Retrieved 2012-01-20.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-10-27. Retrieved 2010-12-03.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- New York Times review http://movies.nytimes.com/movie/review?_r=2&res=950DE3DB1231F93BA35756C0A96E958260

- "Artemisia". Chicago Sun-Times.

- Artemisia : The New Yorker June 1, 1998

Other works inspired by the artist's life

- Alexandra Lapierre:Artemisia: A Novel

- Sally Clark: Life Without Instruction, a play by the Canadian playwright

- Cathy Caplan:Lapis Blue Blood Red, a play which opened off-Broadway in 2002

- Susan Vreeland:The Passion of Artemisia: A Novel

- Rauda Jamis: Artemisia ou La Renommée 1990 (in French, not translated in English yet)

- Anna Banti:Artemisia

Suggested reading

- Mieke Bal, ed: The Artemisia Files; Artemsia Gentileschi for Feminists and Other Thinking People. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2005

- Mary D. Garrard: Artemisia Gentileschi around 1622: The Shaping and Reshaping of an Artistic Identity (The Discovery Series) Also found here

- Mary D. Garrard: Artemisia Gentileschi

- Mary D. Garrard: Artemisia Gentileschi: The Image of the Female Hero in Italian Baroque Art (Princeton University Press, 1989), The book includes the English translation of the artist's 28 letters and testimony of the rape trial of 1612.

- R. Ward Bissell: Artemisia Gentileschi and the Authority of Art. Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999

External links

- Artemisia on IMDb

- Artemisia at Rotten Tomatoes

- Artemisia's moment, article by Mary O'Neill in the Smithsonian magazine, May 2002

- Artemisia at Box Office Mojo