Selenidera

Selenidera is a bird genus containing six species of dichromatic toucanets in the toucan family Ramphastidae. They are found in lowland rainforest (below 1,500 metres or 4,900 feet) in tropical South America with one species in Central America.

| Selenidera | |

|---|---|

| |

| Guianan toucanets (Selenidera culik), from Monograph of the Ramphastidae by John Gould. Female above, male below. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Piciformes |

| Family: | Ramphastidae |

| Genus: | Selenidera Gould, 1837 |

| Species | |

|

6, see text | |

All the species have green upper-parts, red undertail-coverts and a patch of bare blue or blue-green skin around the eye. Unlike most other toucans, the sexes are different in colour (sexually dichromatic; hence the name dichromatic toucanets). The males all have a black crown, nape, throat and breast and an orange/yellow auricular streak. The females of most species have the black sections in the male replaced by rich brown and a reduced/absent auricular streak, while the female of one species, the Guianan toucanet, has grey underparts and a rufous nuchal collar, and the female of another, the yellow-eared toucanet, resemble the male except for its brown crown and lack of an auricular streak. The calls are low-pitched and croaking. Most species are relatively small toucans with a total length of 30–35 cm (12–14 in), but the yellow-eared toucanet typically has a total length of approx. 38 cm (15 in).

They tend to forage alone or in pairs, feeding mainly on fruit. They are fairly quiet and elusive birds which generally keep to dense cover. The nest is a cavity in a tree which the birds enlarge by excavating with their bills. The white eggs are incubated by both parents.

Taxonomy and systematics

The genus Selenidera has six species considered to belong to the genus:[1]

Species

| Image | Scientific name | Common Name | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selenidera spectabilis | Yellow-eared toucanet | Central America |

| Selenidera piperivera | Guianan toucanet | North-western Brazil, French Guiana, Guyana, Suriname, and Venezuela |

| Selenidera reinwardtii | Golden-collared toucanet | Western Amazon rainforest in South America |

| Selenidera nattereri | Tawny-tufted toucanet | Amazon Basin of Venezuela, Brazil, eastern Colombia and western Guyana | |

.jpg) | Selenidera gouldii | Gould's toucanet | South-eastern part of the Amazon rainforest, with a disjunct population in Serra de Baturité in the Brazilian state of Ceará |

| Selenidera maculirostris | Spot-billed toucanet | Atlantic Forest of south-eastern Brazil, far eastern Paraguay, and far north-eastern Argentina |

Speciation in Selenidera

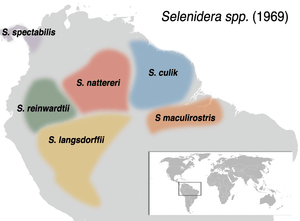

The genus Selenidera was used by the German biologist Jürgen Haffer as an example of the "refugia" hypothesis of speciation. He suggested that the different species evolved from one common ancestor whose population was fragmented by the retreat of the rainforest into the wettest areas during periods of dry climate in the Pleistocene epoch. The single species developed into several species in these isolated refugia. When the forest expanded again during a wetter period, the ranges of the different species expanded until they came into contact with each other, forming a complementary pattern of distributions.

The refugial hypothesis is somewhat disputed as there is little field data to support or reject it. In any case it is simply one of several competing hypotheses to explain Amazonian biodiversity, each of which may or may not provide a good explanation for the geographical pattern found in any one group of taxa. In the present case, the refugia hypothesis is probably correct, as the Amazonian Selenidera have distributions centered on major river systems; they might be considered a superspecies. Some other birds from the region, in contrast, have sister species that are separated by the major rivers, which thus apparently acted as natural barriers to gene flow. Whether a refugia or a barrier model describes superspecies distribution in the Amazonian basin most appropriately thus seems to be a direct consequence of the animals' ability to cross major waterways. But even in the Selenidera toucanets which, though largely sedentary, are technically able to disperse widely, the Amazon River forms a barrier that was simply too wide to cross in significant numbers as to inhibit speciation.

References

- "Jacamars, puffbirds, toucans, barbets & honeyguides « IOC World Bird List". www.worldbirdnames.org. Retrieved 2017-02-20.

- Jürgen Haffer (1969) Speciation in Amazonian Forest Birds, Science, 165:131-137

- Jorge R. Rodriguez Mata, Francisco Erize & Maurice Rumboll (2006) A Field Guide to the Birds of South America, Collins, London

- Christopher Perrins, ed. (2004) The New Encyclopedia of Birds, Oxford University Press, Oxford