Second Luther cabinet

The Second Luther cabinet (German: Zweites Kabinett Luther) was the 13th democratically elected Reichsregierung of the German Reich, during the period in which it is now usually referred to as the Weimar Republic. The cabinet was named after Reichskanzler (chancellor) Hans Luther and was in office for not quite four months. On 20 January 1926 it replaced the First Luther cabinet which had resigned on 5 December 1925. Luther resigned as chancellor on 13 May 1926. His cabinet remained in office as a caretaker government until 17 May 1926, but was led by Otto Gessler in its final days. On 17 May, Wilhelm Marx formed a new government, virtually unchanged from the second Luther cabinet except for the departure of Luther.

Establishment

Talks over the formation of a new government began soon after the German National People's Party (DNVP) left the governing coalition in late October 1925, protesting the Locarno treaties. On 5 November, representatives of Zentrum, German Democratic Party (DDP) and Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) met and discussed a "grand coalition", from the German People's Party (DVP) on the right to SPD on the left. Nothing came of it, first because the SPD insisted on a dissolution of the Reichstag, then because neither SPD nor DVP were willing to commit themselves fully to such a coalition. On 7 December, two days after Luther had resigned as chancellor, president Paul von Hindenburg intervened, calling on the parties to speedily agree on a new government and hinting that, given the economic difficulties of the winter, he would welcome a grand coalition. Zentrum, DDP and DVP agreed to this, but the SPD presented a list of social and economic policy demands as a precondition. This was discussed by the president with the other parties and as a result, Erich Koch-Weser (DDP) was asked on 14 December to form a cabinet based on a grand coalition. After three days, however, Koch-Weser gave up, telling Hindenburg that despite a large degree of flexibility on the part of the DVP, the SPD was not really willing to compromise. Another attempt by Hindenburg in early January also failed due to the differences between SPD and DVP on social policies.[1]

Hindenburg thus asked acting chancellor Luther to try and form a new cabinet based on the parties of the political centre. Luther, although seeming disinterested according to Koch-Weser, won approval from DDP, Zentrum and the Bavarian People's Party (BVP) in talks that took place over the next six days. However, disagreements soon emerged on the distribution of the cabinet posts. The BVP refused to accept Koch-Weser as minister of the interior, arguing he was too much in favour of a unitary rather than a federal state. On 19 January, Hindenburg called on the party leaders to put the interests of the fatherland above their doubts and send him a list of ministers. Luther was able to do so, after the DDP had agreed to Koch-Weser remaining out of the cabinet and to being represented by Wilhelm Külz (Interior) and Peter Reinhold (Finance) instead. Stresemann, Brauns, Gessler, Stingl and Krohne all kept their portfolios. The other new ministers were Wilhelm Marx, chairman of the Zentrum party, DVP Reichstag member Julius Curtius and Heinrich Haslinde, the Regierungspräsident of Münster.[1]

Overview of the members

The members of the cabinet were as follows:[2]

| Second Luther cabinet 20 January to 12/13 May 1926 | ||

|---|---|---|

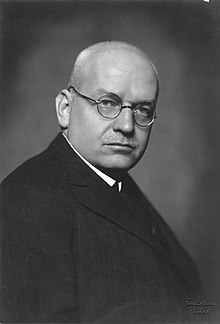

| Reichskanzler | Hans Luther | independent |

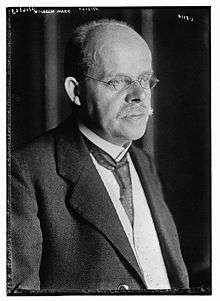

| Reichsministerium des Innern (Interior) | Wilhelm Külz | DDP |

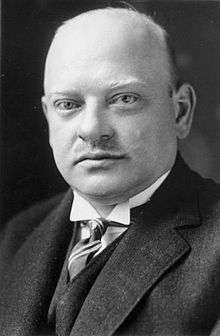

| Auswärtiges Amt (Foreign Office) | Gustav Stresemann | DVP |

| Reichsministerium der Finanzen (Finance) | Peter Reinhold | DDP |

| Reichsministerium für Wirtschaft (Economic Affairs) | Julius Curtius | DVP |

| Reichsministerium für Arbeit (Labour) | Heinrich Brauns | Zentrum |

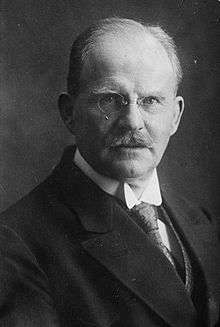

| Reichsjustizministerium (Justice) and Reichsministerium für die besetzten Gebiete (Occupied Territories) |

Wilhelm Marx | Zentrum |

| Reichswehrministerium (Defence) | Otto Gessler | DDP |

| Reichsministerium für das Postwesen (Mail) | Karl Stingl | BVP |

| Reichsministerium für Verkehr (Transport) | Rudolf Krohne | independent |

| Reichsministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft (Food and Agriculture) | Heinrich Haslinde | Zentrum |

Notes: Haslinde was appointed only on 22 January. Luther decided to resign on 12 May 1926 and did so the next day,13 May. Gessler replaced him as acting chancellor until 17 May, when the Third Marx cabinet took office. Marx was acting minister for the occupied territories in addition to his post as minister of justice. [3]

Domestic policies

Important domestic issues were the economic situation, the referendum on the expropriation of the ruling houses and the so-called Flaggenordnung (flag decree) over which the government ultimately fell.[4]

Economic crisis

In the winter 1925/6, the economic situation deteriorated markedly. Consumption declined and so did industrial capacity utilization. Unemployment shot up from 673,000 in early December to 2 million by the start of February. One of the first acts of the new cabinet after the Reichstag had narrowly expressed its confidence was to stimulate the economy. However, these attempts were not very durable as other issues soon took up increasing share of the cabinet's attention, including the expropriation issue, the flag question and a debate over legal sanctions against dueling.[4]

Luther and Reinhold agreed that tax cuts and other measures to stimulate the economy, such as the use of unemployment funds, were urgently needed. Reinhold suggested a reduction of the value-added tax as well as of the merger tax and the stock exchange tax. He argued that these measures were only possible if the Reichstag was prevented from voting extra expenditures without ensuring offsetting revenues. A change in budget law in this regard proved elusive however, and the coalition parties only agreed that decisions having a considerable fiscal impact were to be discussed between the parties and with the cabinet before being tabled.[4]

Protest by winegrowers, at times violent, resulted in a change in the tax law before it was passed in late March. It abolished the wine tax at the cost of limiting the cut in the value-added tax to 0.25 percentage points (from 1% to 0.75%, rather than the 0.5%/0.6% originally planned).[4]

Other measures included a state guarantee of exports to the Soviet Union (totaling 300 million Reichsmark), finally settled only in July 1926. To boost demand, the cabinet decided to provide intermediate credit of 200 million Reichsmark to housing construction, to ameliorate the nationwide lack of 600.000 housing units. A 100 million Reichsmark loan was given to the Deutsche Reichsbahn-Gesellschaft. It used the funds to place orders with the steel, wood and quarrying industries. These were all initial steps towards the large-scale make-work programs begun by the Marx cabinet later that year.[4]

Expropriation of the princes

Besides the state of the economy, the most debated domestic issue of the first half of 1926 was the question of compensation for the former ruling houses of Germany. In 1925, the Reichsgericht had declared the expropriation of the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha from July 1919 to be unconstitutional and repealed it. In reaction, draft bills had been tabled in the Reichstag by Communists (requesting complete expropriation without compensation) and others (giving the Länder the right to finally settle this issue with the noble houses and barring recourse to the courts).[4]

A major conflict erupted in spring 1926 when a referendum on expropriation without compensation was initiated by the SPD and the Communists. Before the referendum, representatives of the coalition parties tried to forestall it by offering the SPD an alternative compromise law. This called for a special court in which these conflicts between noble houses and Länder (state) governments could be addressed. It also included the possibility of declaring a substantial share of the princes' assets as "government property". However, both SPD and DNVP were unwilling to accept this compromise. Talks on the issue ceased on 28 April. A few days earlier the cabinet, on the initiative of the centre parties and the president, had expressed its view on the constitutionality of the compromise law, opining that it would require a two-thirds majority. On 30 April, the cabinet approved a draft law (closely resembling the compromise). On 14 May, the Reichsrat approved this law with a two-thirds majority. The referendum took place on 20 June. Although the vast majority of participating voters voted yes, it failed to achieve the required absolute majority of those entitled to vote.[4]

Flag decree

In early May 1926, Luther secured cabinet approval of a change in the Flaggenordnung. Members of the Hamburg senate had pointed out to him that German minorities in many Latin American countries, for sentimental reasons, only accepted the black-white-red flag of the empire as the symbol of Germany and often came into conflict with the representatives of the foreign service over this. To improve the ties between these expatriate groups and Germany, Luther had suggested in late April to introduce the black-white-red trade flag (approved by the Weimar constitution) as a secondary flag at German embassies in addition to the official black-red-gold flag. However, massive protests by the parliamentary groups of Zentrum, SPD and DDP forced him to change the decree, so that it would apply only at consular institutions in European ports and in non-European locations. The decree was signed by Hindenburg on 5 May, resulting in the SPD announcing its intention to table a no-confidence vote in the Reichstag against the cabinet. The DDP also demanded that the decree be withdrawn, but then seemed to settle for a formal confirmation by the president that the official colours of black-red-gold were not to be questioned.[4]

Hindenburg wrote a letter to Luther in which he confirmed his intention to deal with the flag issue on the basis of the constitution. The DDP was somewhat satisfied but expressed their continued mistrust of Luther. Although the cabinet and the parliamentary groups of the other parties warned against pursuing this issue too far, which could easily lead to the dissolution of the Reichstag or to a presidential crisis, the DDP demanded "personnel change" (i.e. a voluntary resignation by Luther) and a "suspension" of the flag decree. When the latter was refused by the cabinet, the DDP tabled a vote of reprobation directed against the chancellor in the Reichstag.[4]

Luther had announced in the Reichstag that the decree would be implemented at the latest by the end of July 1926 but that the cabinet would be ready to revoke it if parliament and president had found another compromise solution by then. On 12 May, the vote of no confidence initiated by the SPD was clearly rejected in the Reichstag, but the DDP's reprobation vote was accepted with a large majority. Luther now decided to resign immediately and refused pleas from the cabinet and Hindenburg to stay on as head of a caretaker government.[4]

Resignation

The cabinet resigned formally the next day, on 13 May 1926. To ensure continuity of government, Hindenburg had to appoint Otto Gessler as caretaker chancellor until a new cabinet could be formed. On 17 May, the third cabinet of Wilhelm Marx, virtually unchanged from the second Luther cabinet except for the departure of Luther, took office.[4]

References

- "Die Kabinettsbildung (German)". Bundesarchiv. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- "Kabinette von 1919 bis 1933 (German)". Deutsches Historisches Museum. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- "Das Kabinett Luther II (German)". Bundesarchiv. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- "Die Innenpolitik (German)". Bundesarchiv. Retrieved 14 February 2016.