First Luther cabinet

The First Luther cabinet (German: Erstes Kabinett Luther) was the 12th democratically elected Reichsregierung of the German Reich, during the period in which it is now usually referred to as the Weimar Republic. The cabinet was named after Reichskanzler (chancellor) Hans Luther and was in office for only a year. On 15 January 1925 it replaced the Second Marx cabinet which had resigned on 15 December 1924. Luther resigned with his cabinet on 5 December 1925 following the signature of the Locarno treaties but remained in office as caretaker. He formed another government on 20 January 1926.

Establishment

Attempts to form a new government had dragged on since the Marx cabinet resigned on 15 December. Marx himself had been asked by president Friedrich Ebert to build a new coalition. However, the goals of the parties turned out to be incompatible. Including the whole spectrum from SPD to DNVP proved elusive. Moreover, the DDP refused to work with the DNVP, which also ruled out a broad "Bourgeois" coalition. As a result, Marx gave up on 9 January. Hans Luther began talks on 10 January but his initial attempt to form a coalition failed when the Zentrum asked for reassurances that the DNVP would accept a formal declaration of allegiance to the democratic constitution. When Luther was unable to provide those, the plans fell through.[1]

Luther then initiated a second round of negotiations aimed at setting up an alternative to the traditional party-based cabinet. The idea was for DNVP, Zentrum, DVP and BVP to each appoint a "representative" who would not formally be bound by party discipline. These would be joined by several technocrats, who – though nominally without party affiliation – would nevertheless be vetted based on their closeness to political parties. This half-way construct between a purely technocratic government and one based on an explicit coalition of parties would, so Luther hoped, make it easier for the parties not included to support its policies in the Reichstag. Since the SPD had expressed its opposition to a bourgeois government as late as 10 January, Luther apparently was trying to win the support of the DDP.[1]

In fact, on 12 January the Zentrum was only willing to support the new cabinet if the DDP agreed to keep Otto Gessler in office. Luther was able to get this agreement from the DDP's Erich Koch-Weser the next day. The issue that remained to be settled at this point was in which form the cabinet should gain the necessary expression of support of the Reichstag. On 15 January it became obvious that a formal vote of confidence, as preferred by the DNVP was unpopular in the Zentrum parliamentary group. Thus, the parties agreed to settle for a vote of acknowledgement of the government declaration. That same evening, Luther was appointed Reichskanzler (chancellor).[1]

The complete cabinet was presented to the public only on the day of the government declaration, 19 January. Four parties contributed a Vertrauensmann: DVP (Stresemann), Zentrum (Brauns), DNVP (Schiele) and BVP (Stingl). Schiele, since 1914 a member of the Reichstag and since late 1924 head of the DNVP parliamentary group, was the only one among them without previous government experience. Of the four only Stingl was not a member of the Reichstag. Two ministries were awarded to technocrats, not directly associated with a party fraction: Gessler, a DDP member but since 1924 not in the Reichstag any more and von Kanitz. Both had held these exact offices in the previous government. The other portfolios were distributed between the coalition parties, and experts who were close to these parties were then appointed. Otto von Schlieben (DNVP) had previously headed the budget department at the Ministry of Finance. Albert Neuhaus (DNVP), a former head of the trade department of the Reichswirtschaftsministerium who had left public service in 1920 when he refused to swear allegiance to the Weimar Constitution, became Minister of Economic Affairs. The DVP nominated Rudolf Krohne, secretary of state at Transport, to become minister. The Zentrum nominated Josef Fenken for Justice.[1]

Overview of the members

The members of the cabinet were as follows:[2]

| First Luther cabinet 15 January to 5 December 1925 | ||

|---|---|---|

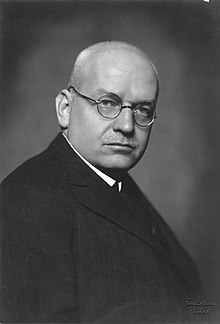

| Reichskanzler | Hans Luther | independent |

| Reichsministerium des Innern (Interior) | Martin Schiele (until 26 October 1925) | DNVP |

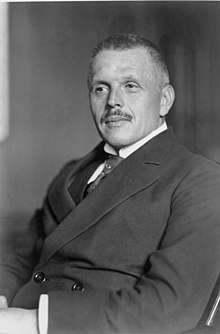

| Auswärtiges Amt (Foreign Office) | Gustav Stresemann | DVP |

| Reichsministerium der Finanzen (Finance) | Otto von Schlieben (until 26 October 1925) | DNVP |

| Reichsministerium für Wirtschaft (Economic Affairs) | Albert Neuhaus (until 26 October 1925) | DNVP |

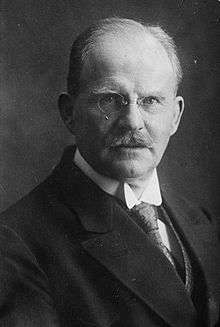

| Reichsministerium für Arbeit (Labour) | Heinrich Brauns | Zentrum |

| Reichsjustizministerium (Justice) and Reichsministerium für die besetzten Gebiete (Occupied Territories) |

Josef Frenken (until 21 November 1925) | Zentrum |

| Reichswehrministerium (Defence) | Otto Gessler | DDP |

| Reichsministerium für das Postwesen (Mail) | Karl Stingl | BVP |

| Reichsministerium für Verkehr (Transport) | Rudolf Krohne | DVP |

| Reichsministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft (Food and Agriculture) | Gerhard von Kanitz | independent |

Notes: The DNVP ministers resigned from the cabinet on 26 October 1925. Gessler took over as acting minister at Interior, Krohne as acting minister at Economy. Luther himself took over the portfolio of Finance. He also took over the Justice portfolio after 21 November 1925, when Frenken resigned in protest over the Locarno treaties. Also from that date, the ministry for the occupied territories was headed by acting minister Brauns.[3]

Foreign policies

In foreign policy, the cabinet's two main tasks were a) to organize the Reich's trade relations with its European neighbours, and b) to settle the issue of the security arrangements in Europe. It was the latter issue which eventually resulted in the resignation of the DNVP ministers.[4]

Security policy and the Locarno Treaties

In 1925, the government's main focus was squarely on dealing with security issues. In December 1924, at a meeting with French Prime Minister Édouard Herriot, British Foreign Secretary Austen Chamberlain had expressed support for a separate treaty between France and Britain, outside of the wider European collective security arrangement that was sought by the League of Nations. Another problem from the German point of view was the decision by the Council of the League that after the end of military occupation of a territory (according to Art. 213), the Council would be allowed to retain permanent observation institutions in the demilitarized zone. France was eager to pursue this and argued for its implementation with regard to the Rhineland. On 10 January 1925, the northern Rhineland zone was due to be vacated by the Allies. They refused to do so and on 5 January justified their decision in a note with vague references to German "breaches of the disarmament clauses of the Treaty of Versailles". Further instructions to Germany as to what was expected in terms of additional disarmament would follow.[4]

This forced the German side to abandon its previous wait-and-see stance. A secret memorandum, presented on 20 January to Britain and on 9 February to France suggested a non-aggression pact between all countries "interested in the Rhine". It also offered a guarantee of the "current status on the Rhine" (i.e. the German-French and German-Belgian borders) and the signing of arbitration agreements with all interested parties. Luther and Foreign Minister Stresemann only informed the rest of the cabinet of the full details of the note two months later. They anticipated strong opposition from the DNVP and feared that a domestic debate would undermine the government's position in negotiations with the Allies as well as threaten the government's cohesion.[4]

During talks about the memorandum, Chamberlain demanded that Germany would join the League with no conditions and as an equal partner. Although the German side agreed to a linkage between League membership and the security question, it stuck to its earlier position that as a disarmed and economically constrained country it would require a special dispensation from Art. 16 of the League, which forced all members to treat war on any other member as an act of aggression and respond with sanctions. More seriously, Chamberlain tried to win a German agreement that under no circumstances would they try to change the status quo on the German-Polish border through military means and accept it as permanent in the same way as the French-German border. This was steadfastly opposed in Berlin, where the cabinet insisted on leeway to change the border by peaceful means and saw the arbitration agreement proposed in the memorandum as sufficient.[4]

By March, concerns started to surface in the DNVP about the government making too many concessions and the parliamentary group soon wrote to Stresemann indicating that they would not agree to any treaties unless the "spirit of the negotiations" changed. By throwing his personal weight behind the foreign policies, Luther was able to defuse the situation and the DNVP members reduced their criticism to complaining about the secretive way in which the Foreign Office had acted. However, Luther also promised greater transparency in the future and the involvement of party representatives. Stresemann said that the government would not change its stance on the Polish border and that he saw the current process as leading towards a speedy return of Cologne and the Ruhr as well as to an Allied withdrawal from the rest of the occupied zone ahead of schedule.[4]

At this point the focus shifted to the disarmament issue. After the government had sharply protested the Allied decision not to vacate the northern Rhineland and asked for an explanation, no further progress had been made. Through unofficial channels, the Reichswehrministerium had managed to gain access to some details of the report by the Military Inter-Allied Commission of Control (CMIC), but it remained unclear which of its findings served as the rationale for the refusal to withdraw. Meanwhile, with no official information available, the foreign press was starting to speculate about significant German breaches of the disarmament clauses, and indeed about secret preparations for war. When no Allied note had been received by mid-May, Stresemann strongly criticized this delay in a Reichstag speech and expressed his hope that any remaining issues the Allies might have would turn out to be minor.[4]

On 4 June, Germany received the Allied response. It contained a surprisingly long list of German infractions, according to Stresemann mainly "petty and pathetic" points. It also made a number of major demands on armament, organization of the armed forces, and police or troop training that could not be reasonably derived from the Treaty articles. However, the northern Rhineland would be vacated as soon as all points had been cleared up. The cabinet now faced a difficult choice: agreeing to the whole list in the interest of regaining control of the Rhineland or to offer to deal only with those points which were clearly based on Germany's obligations under the Treaty. On the suggestion of Stresemann, the cabinet chose the second option and appointed a commission to negotiate with the CMIC.[4]

On 16 June, France replied to the secret German memorandum. It agreed to negotiate a security pact, but demanded a full entry of Germany into the League and acceptance of arbitration agreements. These would be guaranteed by Great Britain, France, Italy and Belgium in the west but by all signatories of the Treaty of Versailles in the east.[4]

Both these Allied communications were made public on 19 June, causing a heated debate of Stresemann's policies. In the cabinet, Frenken, Neuhaus, von Kanitz, Schiele and Hans von Seeckt, the Chef der Heeresleitung or commander in chief of the army, refused to support another voluntary confirmation of the western borders forced on Germany at Versailles. Stresemann refused to conduct further negotiations in such a way that they must fail, as suggested by Frenken. Luther supported his Foreign Minister and the cabinet agreed on further talks with the Allies on these issues for now.[4]

Tensions between Stresemann and Luther emerged, when the chancellor claimed that Stresemann had only informed him about the secret memorandum and the details of German policy on the security issue in mid-February. Stresemann maintained he had always kept him fully informed.[4]

On 20 July, the cabinet's reply to the French note was delivered. Despite taking a critical stance towards the French position on arbitration agreements and confirming German reservations about Art. 16, this found a positive response in Paris. France replied on 24 August, indicating that the exchange of notes could now be replaced with direct talks. In late August, both sides agreed on a meeting of judicial experts to prepare an intergovernmental conference.[4]

In September, Germany received the invitation to the conference of foreign ministers. Schiele, for the DNVP, tried to convince Luther to send only Stresemann so as to keep the person of the chancellor untainted by association with the outcome of the conference. Luther, however, insisted on going himself to add his weight to the German delegation. Schiele insisted on his second demand, however, that the government's reply to the invitation should officially protest the Allied position assigning sole responsibility for World War I to Germany. Stresemann strictly opposed this, fearing the Allied reaction to such a provocation. Nevertheless, a memorandum was added to the German response, sharply rejecting the war guilt claim.[4]

On 2 October, the cabinet agreed on the delegation guidelines: change of the French-British draft discussed at the London expert meeting to make clear that the guarantee of the western border would only mean a renunciation of offensive war and not a waiver of claims to German territory (i.e. Alsace-Lorraine and Eupen-Malmedy); refusal of a French guarantee of the eastern arbitration treaties; interpretation of Art. 16 in a way that took account of German reservations; changes to military rule in the Rhineland and a reduction in the duration of the occupation of the second and third zone of the Rhineland.[4]

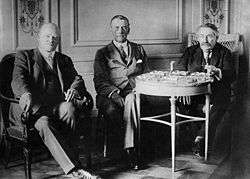

At the Locarno conference (5-16 October), Stresemann and Luther were able to achieve their goals to a sufficient degree with regard to Art. 16, the form of the western security arrangement (also known as Rheinpakt) and the arbitration conventions. No progress was made on the duration of the occupation. No clear reply came from Chamberlain and Aristide Briand on German concerns about the creation of permanent observer institutions in the demilitarized zone: The relevant article's wording was not final and it might never be implemented. No assurances were give by the Allies at the conference regarding the changes to the occupation regime desired by the Germans. On the issue of German infractions of the disarmament agreement, it was agreed that Germany would inform the Allies about the measures it had taken. The conference of Allied ambassadors would then fix a date for withdrawal from the Cologne area and express a firm expectation that Germany would comply with all the demands of the note of 5 January not already fulfilled in the short term.[4]

The ministers who remained in Berlin during the conference were then informed about the results and a majority argued against initialing the treaties and to stick to just protocolling them. Stresemann and Luther, however, refused and on 16 October fully agreed to the results of the negotiations.[4]

When they returned to Berlin, they managed to convince the rest of the cabinet, which met with the Reichspräsident, now Paul von Hindenburg (see below), for these talks, of the necessity of their actions. On 22 October the cabinet agreed unanimously to bring the treaties into force. Yet within hours, the DNVP fraction sharply criticized the results of Locarno and declared that it would not be able to support any treaty that "sacrificed German territory or people". Luther and Schiele tried to calm the waves by way of a government declaration stating that Art. 1 of the treaty only implied a renouncement of war, not of the right of self-determination or peaceful changes to the borders. However, since this note was treated confidentially and not transmitted to the Allies as demanded by the DNVP, its Reichstag group voted to leave the coalition on 25 October.[4]

As a result, Schiele, Schlieben and Neuhaus all resigned their posts. The remaining ministers agreed that the Reichstag should not be dissolved and that the government should remain in office, as that would be the only way of getting the parliament's approval for the treaties in time for their formal signing on 1 December. Hindenburg agreed to this as well as to Luther's suggestion to have the vacant portfolios be taken over by existing members of the cabinet on a caretaker basis. Even the DNVP announced that it would refrain from tabling a motion of no confidence.[4]

Meanwhile, the French government agreed to a number of changes to the occupation regime in the Rhineland, and in mid-November officially informed the German government. Although less than perfectly satisfied with the results, the cabinet agreed that the drawbacks were not sufficient to sink the treaties on their account. It was also viewed as just a first step towards the desired "hollowing out" of the Treaty of Versailles.[4]

Disarmament issues were dealt with in a German-Allied exchange of views, that ended in mid-November with a mutual satisfying agreement: police forces in barracks would be limited to 32,000, the position of Chef der Heeresleitung was changed to make the senior commanders directly responsible to the "Reichswehrminister", making the chief just a councilor and deputy to the minister. Germany also agreed to dissolve paramilitary associations. A note from the conference of Allied ambassadors declared itself satisfied with these results and announced the withdrawal from the first Rhineland zone for December 1925 and January 1926. On 17 November the cabinet decided to put the Locarno treaties to a Reichstag vote. Although strongly opposed by the DNVP they passed with a large majority on 27 November and were signed by Hindenburg a day later.[4]

Domestic policies

Although the most crucial issues facing the cabinet were in the field of foreign policy, it also had some lasting impact on domestic policies. The government notably left its mark on tax law, the financial relations between Reich, Länder and municipalities and social law. It also had to deal with the sudden death of the head of state.[5]

Death of Friedrich Ebert and presidential election

President Ebert fell acutely ill in mid-February and died on 28 February. In accordance with Article 51 of the constitution, Luther took over the responsibilities of the head of state when Ebert fell ill. Government work was disrupted, first as the memorial events for Ebert had to be organized, then as debates dragged on over the details of the presidential election and the question of who would substitute for Ebert until his successor could be elected. The parliamentary groups became increasingly engaged in the election campaign, which put a burden on the work of the cabinet.[5]

After protests by SPD and DDP against Luther's double role as chancellor and acting president, he agreed to have the Reichstag decide the issue. A law of 10 March appointed Walter Simons, president of the Reichsgericht, the highest court, as acting head of state.[5]

During the election campaign, Luther was at pains to emphasize the neutrality of the government but noted that he personally would not refrain from influencing the choice of candidates and working to prevent damage to the interests of the Reich. He was particularly worried about Paul von Hindenburg, whose decision to run had caused very critical reactions in the foreign press. Luther tried to convince Simons to approach Hindenburg and Marx, the two main candidates in the second round of voting and ask them to withdraw from the running in Simons' favour. Simons refused, noting that Hindenburg had once publicly called him a traitor to the fatherland and would be unlikely to withdraw.[5]

Hindenburg was elected and in subsequent talks between the government and the president-elect, he expressed some reservations about the cabinet's policies but indicated his desire to govern "only constitutionally". He indicated that he had no plans to make use of his powers to dismiss the chancellor and agreed to the current cabinet staying in office with no personnel changes.[5]

Resignation

On 1 December, the Locarno Treaties were signed in London. As announced previously, the cabinet resigned shortly after this central goal was achieved, on 5 December. They were asked to remain in office as caretakers until a new government could be formed. On 13 January 1926, Luther was asked by Hindenburg to form another cabinet, which he did on 20 January.[6]

References

- "Die Kabinettsbildung (German)". Bundesarchiv. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- "Kabinette von 1919 bis 1933 (German)". Deutsches Historisches Museum. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- "Die Kabinette Luther I und II (German)". Bundesarchiv. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- "Außenpolitik 1925 (German)". Bundesarchiv. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- "Innenpolitik 1925 (German)". Bundesarchiv. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- "Die Kabinettsbildung (German)". Bundesarchiv. Retrieved 20 January 2016.