Johannes Trithemius

Johannes Trithemius (/trɪˈθɛmiəs/; 1 February 1462 – 13 December 1516), born Johann Heidenberg, was a German Benedictine abbot and a polymath who was active in the German Renaissance as a lexicographer, chronicler, cryptographer, and occultist. He had considerable influence on the development of early modern and modern occultism. His students included Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa and Paracelsus.

Johannes Trithemius | |

|---|---|

Detail of Tomb Relief of Johannes Trithemius by Tilman Riemenschneider | |

| Born | 1 February 1462 |

| Died | 13 December 1516 (aged 54) |

| Nationality | German |

| Alma mater | University of Heidelberg |

| Known for | Steganographia, Polygraphiae, Trithemius cipher |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Theology, cryptography, lexicography, history, occultism |

| Institutions | Benedictine abbey of Sponheim, St. Jakob zu den Schotten |

| Notable students | Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa Paracelsus |

| Influences | Jakob Wimpfeling[1] Nicholas of Cusa[2] |

Early life

The byname Trithemius refers to his native town of Trittenheim on the Moselle River, at the time part of the Electorate of Trier.

When Johannes was still an infant his father Johann von Heidenburg died. His stepfather, whom his mother Elisabeth married seven years later, was hostile to education and thus Johannes could only learn in secret and with many difficulties. He learned Greek, Latin, and Hebrew. When he was 17 years old he escaped from his home and wandered around looking for good teachers, travelling to Trier, Cologne, the Netherlands, and Heidelberg. He studied at the University of Heidelberg.

Career

Travelling from the university to his home town in 1482, he was surprised by a snowstorm and took refuge in the Benedictine abbey of Sponheim near Bad Kreuznach. He decided to stay and was elected abbot in 1483, at the age of twenty-one. He set out to transform the abbey from a neglected and undisciplined place into a centre of learning. In his time, the abbey library increased from around fifty items to more than two thousand. He often served as featured speaker and chapter secretary at the Bursfelde Congregation's annual chapter from 1492 to 1503, the annual meeting of reform-minded abbots. Trithemius also supervised the visits of the Congregation's abbeys.

Trithemius wrote extensively as a historian, starting with a chronicle of Sponheim and culminating in a two-volume work on the history of Hirsau Abbey. His work was distinguished by mastery of the Latin language and eloquent phrasing, yet it was soon discovered that he inserted several fictional passages into his works. His work as a historian has been tainted ever since, the invented passages proved by several scholars.[3]

However, his efforts did not meet with praise, and his reputation as a magician did not further his acceptance. Increasing differences with the convent led to his resignation in 1506, when he decided to take up the offer of the Bishop of Würzburg, Lorenz von Bibra (bishop from 1495 to 1519), to become the abbot of St. James's Abbey, the Schottenkloster in Würzburg. He remained there until the end of his life.

Death

Trithemius was buried in this abbey's church; a tombstone by the famous Tilman Riemenschneider was erected in his honor. In 1825, the tombstone was moved to the Neumünster church, next to the cathedral. It was damaged in the firebombing of 1945, and subsequently restored by the workshop of Theodor Spiegel.

Legacy

Notably, the German polymath, physician, legal scholar, soldier, theologian, and occult writer Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa (1486–1535) and the Swiss physician, alchemist, and astrologer Paracelsus (1493–1541) were among his pupils.

Steganographia

Trithemius' most famous work, Steganographia (written c. 1499; published Frankfurt, 1606), was placed on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum in 1609[4] and removed in 1900.[5] This book is in three volumes, and appears to be about magic—specifically, about using spirits to communicate over long distances. Since the publication of the decryption key to the first two volumes in 1606, they have been known to be actually concerned with cryptography and steganography. Until recently, the third volume was widely still believed to be solely about magic, but the "magical" formulae have now been shown to be covertexts for yet more cryptographic content.[6][7] However, mentions of the magical work within the third book by such figures as Agrippa and John Dee still lend credence to the idea of a mystic-magical foundation concerning the third volume.[8][9] Additionally, while Trithemius's steganographic methods can be established to be free of the need for angelic–astrological mediation, still left intact is an underlying theological motive for their contrivance. The preface to the Polygraphia equally establishes, the everyday practicability of cryptography was conceived by Trithemius as a "secular consequent of the ability of a soul specially empowered by God to reach, by magical means, from earth to Heaven".[10] Robert Hooke suggested in the chapter Of Dr. Dee's Book of Spirits, that John Dee made use of Trithemian steganography, to conceal his communication with Queen Elizabeth I.[11] Amongst the codes used in this book is the Ave Maria cipher where each coded letter is replaced by a short sentence about Jesus in latin.[12]

Works

- Exhortationes ad monachos, 1486

- De institutione vitae sacerdotalis, 1486

- De regimine claustralium, 1486

- De visitatione monachorum, about 1490

- Catalogus illustrium virorum Germaniae, 1491–1495

- De laude scriptorum manualium, 1492 (printed 1494) Zum Lob der Schreiber; Freunde Mainfränkischer Kunst and Geschichte e. V., Würzburg 1973, (Latin/German)

- De viris illustribus ordinis sancti Benedicti, 1492

- In laudem et commendatione Ruperti quondam abbatis Tuitiensis, 1492

- De origine, progressu et laudibus ordinis fratrum Carmelitarum, 1492

- Liber penthicus seu lugubris de statu et ruina ordinis monastici, 1493

- De proprietate monachorum, before 1494

- De vanitate et miseria humanae vitae, before 1494

- Liber de scriptoribus ecclesiasticis, 1494

- De laudibus sanctissimae matris Annae, 1494

- De scriptoribus ecclesiasticis, 1494[13]

- Chronicon Hirsaugiense, 1495–1503

- Chronicon Sponheimense, c. 1495-1509 - Chronik des Klosters Sponheim, 1024-1509; Eigenverlag Carl Velten, Bad Kreuznach 1969 (German)

- De cura pastorali, 1496

- De duodecim excidiis oberservantiae regularis, 1496

- De triplici regione claustralium et spirituali exercitio monachorum, 1497

- Steganographia, c. 1499

- Chronicon successionis ducum Bavariae et comitum Palatinorum, c. 1500-1506

- Nepiachus, 1507

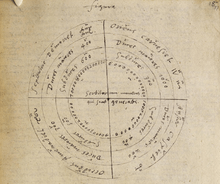

- De septem secundeis id est intelligentiis sive spiritibus orbes post deum moventibus, c. 1508[14] (The Seven Secondary Intelligences, 1508), a history of the world based on astrology;

- Antipalus maleficiorum, 1508

- Polygraphia, 1508

- Annales Hirsaugienses, 1509–1514. The full title is Annales hirsaugiensis...complectens historiam Franciae et Germaniae, gesta imperatorum, regum, principum, episcoporum, abbatum, et illustrium virorum, Latin for "The Annals of Hirsau...including the history of France and Germany, the exploits of the emperors, kings, princes, bishops, abbots, and illustrious men". Hirsau was a monastery near Württemberg, whose abbot commissioned the work in 1495, but it took Trithemius until 1514 to finish the two-volume, 1,400-page work. It was first printed in 1690. Some consider this work to be one of the first humanist history books.

- Compendium sive breviarium primi voluminis chronicarum sive annalium de origine regum et gentis Francorum, c. 1514

- De origine gentis Francorum compendium, 1514 - An abridged history of the Franks / Johannes Trithemius; AQ-Verlag, Dudweiler 1987; ISBN 978-3-922441-52-6 (Latin/English)

- Liber octo quaestionum, 1515

- Compilations

- Marquard Freher, Opera historica, Minerva, Frankfurt/Main, 1966

- Johannes Busaeus, Opera pia et spiritualia (1604 and 1605)

- Johannes Busaeus, Paralipomena opuscolorum (1605 and 1624)

See also

- Augustus the Younger, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg

- Humanism in Germany

- Minuscule 96 – written by the hand of Trithemius

- Tabula recta

- Trithemius cipher

Notes

- Barbara Crawford Halporn (2000). The Correspondence of Johann Amerbach: Early Printing in its Social Context, University of Michigan Press, p. 65.

- Johannes Jansson (1896). The History of the German People at the Close of the Middle Ages vol. 1. pg. 3.

- Arnold, Klaus (1991). Johannes Trithemius (1462–1516). Quellen und Forschungen zur Geschichte des Bistums und Hochstifts Würzburg, 23 (English = Sources and research on the history of the diocese and bishopric of Würzburg, #23) (in German) (2. Aufl. ed.). Würzburg: Schöningh. pp. 144–157. ISBN 978-3-877170-23-6. OCLC 470202364.

2., bibliographisch und überlieferungsgeschichtlich neu bearb. Aufl. (English = 2nd Edition, updated bibliographical and historical lore)

- Indice de Libros Prohibidos (1877) [Index of Prohibited Books of Pope Pius IX (1877)] (in Spanish). Vatican. 1880. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

- Index Librorum Prohibitorum (1900) [Index of Prohibited Books of Pope Leo XIII (1900)] (in Latin). Vatican. 1900. p. 298. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

index librorum prohibitorum tricassinus.

- Reeds, Jim (1998). "Solved: The ciphers in book III of Trithemius's Steganographia". Cryptologia. 22 (4): 191–317. doi:10.1080/0161-119891886948.

- Ernst, Thomas (1996). "Schwarzweiße Magie: Der Schlüssel zum dritten Buch der Stenographia des Trithemius". Daphnis: Zeitschrift für Mittlere Deutsche Literatur. 25 (1): 1–205.

- Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas, The Western Esoteric Traditions: A Historical Introduction (Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), pp. 50-55

- Walker, D. P. Spiritual & Demonic Magic from Ficino to Campanella (Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2003), pp. 86-90

- Brann, Noel L., "Trithemius, Johannes", in Dictionary of Gnosis & Western Esotericism, ed. Wouter J. Hanegraff (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2006), pp. 1135-1139.

- Robert Hooke (1705). The Posthumous Works of Robert Hooke. Richard Waller, London. p. 203.

- Predel, B. (1994), "Cr-Cs (Chromium-Caesium)", Cr-Cs – Cu-Zr, Landolt-Börnstein - Group IV Physical Chemistry, 5d, Springer-Verlag, p. 1, doi:10.1007/10086090_968, ISBN 3540560734

- Digital Version MGH-Bibliothek Archived 2007-06-30 at the Wayback Machine

- Trithemius, Johannes (1522). "De septem secunda Deis id est intelligentiis sive spiritibus moventibus ... - Johannes Trithemius - Google Books". google.com.

References

- Brann, N. L. (1981). The Abbot Trithemius, Leiden: Brill

- Kahn, David (1967). The Codebreakers: the Story of Secret Writing, 1967, 2nd edition 1996, pp. 130–137 ISBN 0-684-83130-9

- Kuhn, Rudolf (1968). Großer Führer durch Würzburgs Dom und Neumünster: mit Neumünster-Kreuzgang und Walthergrab, p. 108

- Wolfe, James Raymond (1970). Secret Writing: the Craft of the Cryptographer. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 112–114.

- Christel Steffen (1969). "Untersuchungen zum "Liber de scriptoribus ecclesiasticis" des Johannes Trithemius", Aus: Archiv für Geschichte des Buchwesens Bd 10, Lfg 4 - 5 [1969] 1247 - 1354.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Johannes Trithemius. |

- Works by or about Johannes Trithemius at Internet Archive

- Steganographia (Latin). Digital Edition, 1997

- Steganographia (Latin). Google Books, 1608 edition

- Steganographia (Latin). Google Books, 1621 edition

- Solved: The Ciphers in Book iii of Trithemius's Steganographia, PDF, 208 kB

- Hill Monastic Manuscript Library article on Trithemius (includes links to photographs of various Trithemius first editions.)

- (in Italian) The complete and solved Steganography books

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Polygraphiae libri sex Ioannis Trithemij From George Fabyan Collection at the Library of Congress

- Steganographia qvæ hvcvsqve a nemine intellecta From George Fabyan Collection at the Library of Congress

- Trithemius Redivivus Translations and resources pertaining to the Steganographia of Johannes Trithemius

- Literature by and about Johannes Trithemius in the German National Library catalogue

- Works by and about Johannes Trithemius in the Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek (German Digital Library)

- "Johannes Trithemius". Repertorium "Historical Sources of the German Middle Ages" (Geschichtsquellen des deutschen Mittelalters).

- Latin works in the Analytic Bibliography of On-Line Neo-Latin Texts

- De septem secundeis in German translation (Über die sieben Erzengel, die nach dem Willen Gottes die Planeten bewegen und die Geschicke der Welt lenken)

- Johannes Trithemius Gemeinde Trittenheim