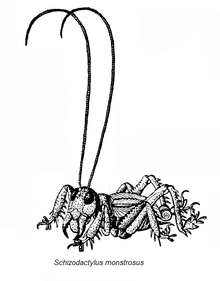

Schizodactylus monstrosus

Schizodactylus monstrosus or the maize cricket, is a species of large, robust cricket found in Asia, belonging to the family Schizodactylidae.[1][2] It is found mainly in sandy habitats along rivers, and has large flattened tarsal extensions and wings that are curled at the tip, right above the cerci.[1][3] They are nocturnal and show a high degree of variation in activity during the day and night. They hide in burrows that they dig on their own during the day.[4][5]

| Schizodactylus monstrosus | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Orthoptera |

| Suborder: | Ensifera |

| Family: | Schizodactylidae |

| Genus: | Schizodactylus |

| Species: | S. monstrosus |

| Binomial name | |

| Schizodactylus monstrosus (Drury, 1773) | |

Description

S. monstrosus adults are approximately 4 cm long, with the coloration being typical of that of a nocturnal or burrowing insect, an overall light yellow with black sections on the back and a lighter green on the belly.[1] They have long, filiform antennae extending longer than their body, with the scape being white with a black dot and the rest of the antennae brown.[2] The wings of S. monstrosusare longer than the body and spiral up at the ends, over the cerci, when at rest.[2] The labrum is large and covers the mandibles.[2] The cerci are white, flexible and have many sensory hairs.[2] Some instars of S. monstrosus have darker bodies than the adults but are overall very similar in shape and color.[2]

Habitat

The preferred habitat of S. monstrosus is along the sandy banks of rivers, including the Indus and Damodar River in Pakistan, along with India, Ceylon (now known as Sri Lanka), and Myanmar.[6][7][5] It had been observed that S. monstrosus use their strong mandibles to aid in digging and use the spurs of their hind tibia to move sand out of the way as they dig.[1] They are known to make burrowsin soil that is very humid and will dig deeper until they find their desired moisture content, humidity of 88.5-98.5% was found to be the most common for a burrow in one study.[6] Burrows are occupied by either a single male or single female.[1] Burrows are most often plugged with sand after they are completed in both adults and nymphs, although a few rare open burrows have been found that there is yet to be an explanation for.[1] As the insect matures and reaches a new instar, they dig a wider, deeper and longer burrow with the diameter ranging between 1/4 to 1 1/4 inches.[2] Adults often go up to two feet below the surface where as nymphs remain in the top layer of sand.[2]

Diet

It has been noted that a closely related species S. inexspectatus is carnivorous and this species is also expected to be carnivorous.[8] T B Fletcher declared that an individual in captivity did not feed on any vegetable matter.They are known to be cannibalistic in captivity as adults as well as nymphs.[9][2] Older nymphs have been found to eat younger nymphs and adult females have been found to eat adult males and vice versa.[10] S. monstrosus that become injured or lose limbs and are unable to escape from other S. monstrosus often quickly become a meal.[10] In its natural habitat, S. monstrosus appears to feed mostly on ground beetles, grasshoppers and crickets.[1] It was also observed that S. monstrosus would often attack prey if it came in or near its burrow, making an easy meal.[1] In the lab, S. monstrosus ate raw meat and fish but showed more interest in living beetles.[10] It attacks prey quickly, latches on using its strong mandibles, and immediately starts chewing it using its well developed molars.[10]

Life Cycle

The mating of S. monstrosus is short as they are compromised while mating and are susceptible to an attack by another member of their species, being that they are carnivorous.[1] The life cycle of S. monstrosus includes 9 instars and takes roughly one year to complete.[1] Eggs are laid at the bottom of the females burrow at an average depth of 14.05 cm and on average 23.10 eggs were laid.[1] The females lay eggs where a newly hatched nymph can access food easily.[1]

Physiology

The overall amount of free haemocyte within S. monstrosus has been found to decrease as they age, possibly thought to trigger senescence due to the creation of abnormalities within the insect. [11]

Culture

These crickets are a favourite food for many tribes in Arunachal Pradesh.[12]

References

- Channa, Sabir Al; Sultana, Riffat; Wagan, Muhammad Saeed (2011). "Studies on the immature stages and burrow excavating behaviour of Schizodactylus monstrosus (Drury) (Grylloptera: Gryllodea: Schizodactylidae) from Sindh, Pakistan". African Journal of Biotechnology. 10: 2328–2333.

- Khattar, N. (1972). "A description of the adult and the nymphal stages of Schizodactylus monstrosus (Drury) (Orthoptera)". J. Nat. Hist. 6 (5): 589–600. doi:10.1080/00222937200770521.

- McClung, C. E. (1933). "The chromosomes of Schizodactylus monstrosus". Journal of Morphology. 55: 185–191. doi:10.1002/jmor.1050550111.

- Islam, A.S. (1982). "Diurnal rhythm of hemocyte population in an insect, Schizodactylus monstrosus Drury". Experientia. 38 (5): 567–569. doi:10.1007/BF02327052.

- Channa, Sabir Ali; Sultana, Riffat; Wagan, Muhammad Saeed (2013). "Morphology and burrowing behaviour of Schizodactylus minor (Ander, 1938) (Grylloptera: Schizodactylidae: Orthoptera) of Pakistan". Pakistan Journal of Zoology. 45: 1191–1196.

- A K Hazra; R S Barman; S K Mondal; D K Choudhuri (1983). "Population ecology of Schizodactylus monstrosus (Drury) (Orthoptera) along the sand bed of Damodar river, West Bengal, India" (PDF). Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences. 92 (6): 453–466. doi:10.1007/BF03186217.

- Hazra, A.K. & Tandon, S.K. (1991). "Ecology and behaviour of a sand burrowing insect, Schizodactylus monstrosus (Orthoptera: Schizodactylidae)". Advances in Management and Conservation of Soil Fauna (Eds: G.K. Veeresh, D. Rajagopal and C.A. Viraktamath). pp. 805–809.

- "The biology, nymphal stages, and life habits of the endemic sand dune cricket Schizodactylus inexpectatus (Werner, 1901) (Orthoptera: Schizodactylidae)" (PDF). Turk. J. Zool. 32: 427–432. 2008.

- Choudhuri, D.K. & Bagh, R.K. (1974). "On the sub-social behaviour and cannibalism in Schizodactylus monstrosus (Orthoptera: Schizodactylidae)". Rev. Ecol. Biol. Sol. 11: 569–573.

- Khattar, Narain (1972). "Anatomy of the digestive organs of Schizodactylus monstrosus Drury Orthoptera". Journal of Natural History. 6: 575–588.

- Mandal, Sanjay (1985). "Haemogram change during senescence processes in Schizodactylus monstrosus D (Orthoptera: Schizodactylidae)". Current Science. 54: 1013–1016.

- Chakravorty, Jharna (2009). Entomophagy, an ethnic cultural attribute to control increased insect population due to global climate change:A case study (PDF). 7th International Science Conference on Human Dimensions of Global Environmental Change, Bonn.