Stefano di Giovanni

For the village near Livorno, see Sassetta, Tuscany

Sassetta | |

|---|---|

_-_WGA20849.jpg) Detail of il Sassetta's Ispirazione di San Tommaso, 1423, Museum of Art, Budapest | |

| Born | Stefano di Giovanni di Consolo around 1392 |

| Died | 1450 or 1451 (age 58 or 59) |

| Nationality | Sienese |

| Known for | Painting |

Stefano di Giovanni di Consolo, known as il Sassetta (ca.1392–1450 or 1451) was an Italian painter who is considered one of the most important representatives of Sienese Renaissance painting.[1] While working within the Sienese tradition, he innovated the style by introducing elements derived from the decorative Gothic style and the realism of contemporary Florentine innovators as Masaccio.[2]

Life and Works

The name Sassetta has been associated with him, mistakenly, only since the 18th century but is now generally used for this artist.[2] The date and birthplace of Sassetta are not known. Some say he was born in Siena although there is also a hypothesis that he was born in Cortona. His father, Giovanni, is called da Cartona which possibly means that Cortona was the artist's birthplace. The meaning of his nickname Sassetta is obscure and is not cited in documents of his time but appears in sources from the eighteenth century.[1]

Sassetta was probably trained alongside artists like Benedetto di Bindo and Gregorio di Cecco but he had a style all of his own. He achieved a high level of technical refinement and was aware of artistic innovations of talented painters in Florence such as Gentile da Fabriano and Masolino. His work differs from the late Gothic style of many of his Sienese contemporaries.[3]

His first certain work, which originally had his signature, is the Arte della Lana altarpiece, (1423–1426) fragments of which are now divided among various private and public collections.[3]

The Madonna of the Snow altarpiece for the Siena Cathedral was a prestigious commission for Sassetta, and is considered his second major work. Not only does he excel at infusing his figures with a natural light that convincingly molds their shape, he also has an amazing handle on spatial relationships, creating cohesive and impressive work.[3] From this point on, under Gothic influence, Sassetta’s style increases its decorative nature. The polyptych done by Sassetta in San Domenico at Cortona (around 1437) depicts scenes from the legend of St. Anthony the Abbot. He shows great skill in narration through his painting as well as combining a sophisticated color palette and rhythmic compositions.[4]

Francesco di Giorgio e di Lorenzo, better known as Vecchietta, is said to have been his apprentice.[4]

He died from pneumonia contracted while decorating the Assumption fresco on the Porta Romana of Siena. The work was finished by his pupil Sano di Pietro.

Many consider Sassetta's fusing of traditional and contemporary elements as integral to the move from the Gothic to the Renaissance style of painting in Siena.[4]

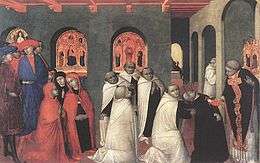

A Miracle of the Eucharist

Sassetta was a fiercely pious man. The painting is about the "marriage of righteousness and violence" and the "consequences of sinfulness, the perils of feigning faith and the power of God."[5]

The figure in black in the painting is an unbeliever, who has been found out in the process of receiving Communion. The officiating priest offers him the host on a plate, which is pictured miraculously spurting blood. The unbeliever has been struck dead instantly, and the creature above his face is a tiny black devil which has swooped down to snatch away his soul to the depths of Hell. The other men pictured are Carmelite monks, caught in expressions of shock, amazement and disgust. The painting is a "carefully staged, meticulously created illusion" which commemorates the Miracle of Bolsena which is said to have taken place in 1263.[5] Sassetta's Altarpiece of the Eucharist was later divided between three museums (British, Hungarian and Italian), the Vatican, and a private collection.[5]

The Borgo San Sepolcro Altarpiece

The altarpiece was originally painted in Siena, and transported to Sansepolcro for placement in the church of San Francesco. In October 1900 the Berenson family purchased three panels created by Stefano di Giovanni. The Berensons' collection consisted of St. Francis in Glory, flanked by the standing Blessed Ranieri and St. John the Baptist, which scholars determined are only a part of a complex altar which had now become scattered among twelve collections throughout Europe and North America.[6] It is generally accepted by the art historical community that Sassetta’s San Francesco altarpiece was one of the largest and most expensive of the Quattrocento.[7] The fact that it was produced by a Sienese artist in Siena, and shipped to the Tiber valley town in late spring 1444 also speaks to Sassetta's fame in his time period.

Bernard Berenson bequeathed many of Sassetta's painting from his Florence Villa to Harvard University, in what became the Center for Italian Renaissance Studies in Florence.[6] A 3D computer-assisted reconstruction of the altarpiece's surviving parts is featured in Sassetta: The Borgo San Sepolcro Altarpiece, edited by Machtelt Israels and released in 2009.[6]

Controversy

There is some contention in the historical art community over which Sienese masters were directly responsible for which paintings. Scenes from the life of St. Anthony of Egypt have been questioned as Sassetta's own work, and critics such as Donald Bruce believe that near-equals, such as the Griselda master also deserve attention for their achievements in art of this time period.[8]

Selected works

- Meeting of Saint Antonio and Saint Paul (c. 1440), tempera on wood, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., USA

- Vision of Saint Thomas of Aquino before the Cross, (1423), Pinacoteca Vaticana

- Saint Thomas inspired by the dove of the Holy Spirit, tempera on wood, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

- Madonna of the Snows Altarpiece (c. 1430–1432), Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

- A predella of three works at the Detroit Institute of Arts

- San Domenico da Cortona Polyptych (c. 1434), Diocesan Museum, Cortona, Italy

- The Journey of the Magi (1435) Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

- Saint Anthony the Hermit Tortured by Devils, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena

- Virgin and Child Adored by Six Angels (1437–44), Louvre Museum, Paris, France

- The Burning of a Heretic (1423), National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia

- Last Supper (1423), Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena

- Ecstasy of Saint Francis (1437–44), Villa I Tatti, Settignano, Italy

- The Miracle of the Eucharist, Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle, United Kingdom

- Saint Francis receiving stigmata (1437–44), National Gallery, London, United Kingdom

- Mystic Marriage of St. Francis (c. 1450), Musée Condé, Chantilly, France

References

- Judy Metro, Italian Paintings of the Fifteenth Century. National Gallery of Art, Oxford University Press: Oxford, New York, 2003. p. 621

- Marco Torriti. "Sassetta." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 9 Mar. 2016

- Miklós Boskovits; National Gallery of Art (U.S.); et al, Italian paintings of the fifteenth century (Washington: National Gallery of Art; New York, 2003), p. 623.

- Sassetta, Italian painter at Encyclopædia Britannica, 2012.

- Andrew Graham-Dixon, Paper Museum: Writings about Paintings, mostly (New York : Knopf, 1997), p. 34–35.

- Fabrizio Nevola. “Reviews” Renaissance Quarterly (University of Chicago Press 2010). Vol. 63, No. 2, pp. 589–591.

- Machtelt Israels, ed. Sassetta: The Borgo San Sepolcro Altarpiece. 2 vols. Florence: Villa I Tatti, 2009, p. 302.

- Donald Bruce, "Sienese Painting at the London National Gallery". Contemporary Review; Winter2007, Vol. 289 Issue 1687, p. 481.

Sources

- Italian Paintings of the Fifteenth Century. 2003 Judy Metro, National Gallery of Art, Oxford University Press: Oxford, New York p. 621.

- Andrew Graham-Dixon, Paper Museum: Writings about Paintings, mostly (New York : Knopf, 1997), 33–36.

- Miklós Boskovits; National Gallery of Art (U.S.); et al., Italian paintings of the fifteenth century (Washington : National Gallery of Art ; New York, 2003), 621–625.

- Machtelt Israels, ed. Sassetta: The Borgo San Sepolcro Altarpiece. 2 vols. Florence: Villa I Tatti, 2009.

- Fabrizio Nevola. “Reviews” Renaissance Quarterly (University of Chicago Press 2010). Vol. 63, No. 2, p. 589–591.

- Donald Bruce, Sienese Painting at the London National Gallery. Contemporary Review; Winter2007, Vol. 289 Issue 1687, p. 481.

- Luciano Bellosi, Sassetta e i pittori toscani tra XIII e XV secolo, a cura di Luciano Bellosi e Alessandro Angelini, Studio per edizioni scelte, Firenze 1986

- B. Berenson, Sassetta, Firenze 1946

- Enzo Carli, Sassetta's Borgo San Sepolcro Altarpiece, in: Burlington Magazine 43, 1951, ss. 145

- Enzo Carli, Sassetta e il «Maestro dell'Osservanza», Milano 1957

- Enzo Carli, I Pittori senesi, Milano 1971

- J. Pope-Hennessy, Sassetta, Londra 1939

- J. Pope-Hennessy, Rethinking Sassetta, in: Burlington Magazine 98, 1956, ss. 364

- Federico Zeri, Towards a Reconstruction of Sassetta's Arte della Lana Triptych, in Burlington Magazine 98, 1956, ss. 36