Sarcomere

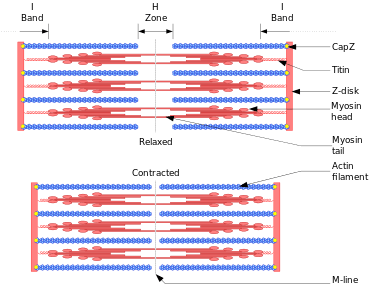

A sarcomere (Greek σάρξ sarx "flesh", μέρος meros "part") is the complicated unit of striated muscle tissue. It is the repeating unit between two Z lines. Skeletal muscles are composed of tubular muscle cells (myocytes called muscle fibers or myofibers) which are formed in a process known as myogenesis. Muscle fibers contain numerous tubular myofibrils. Myofibrils are composed of repeating sections of sarcomeres, which appear under the microscope as alternating dark and light bands. Sarcomeres are composed of long, fibrous proteins as filaments that slide past each other when a muscle contracts or relaxes. The costamere is a different component that connects the sarcomere to the sarcolemma.

| Sarcomere muscle bands | |

|---|---|

Image of sarcomere | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Striated muscle |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | sarcomerum |

| MeSH | D012518 |

| TH | H2.00.05.0.00008 |

| Anatomical terms of microanatomy | |

Two of the important proteins are myosin, which forms the thick filament, and actin, which forms the thin filament. Myosin has a long, fibrous tail and a globular head, which binds to actin. The myosin head also binds to ATP, which is the source of energy for muscle movement. Myosin can only bind to actin when the binding sites on actin are exposed by calcium ions.

Actin molecules are bound to the Z line, which forms the borders of the sarcomere. Other bands appear when the sarcomere is relaxed.[1]

A muscle fiber from a biceps muscle may contain 100,000 sarcomeres.[2] The myofibrils of smooth muscle cells are not arranged into sarcomeres.

Bands

The sarcomeres are what give skeletal and cardiac muscles their striated appearance,[1] which was first described by Van Leeuwenhoek.[3]

- A sarcomere is defined as the segment between two neighbouring Z-lines (or Z-discs, or Z bodies). In electron micrographs of cross-striated muscle, the Z-line (from the German "Zwischenscheibe", the disc in between the I bands) appears as a series of dark lines. They act as an anchoring point of the actin filaments.

- Surrounding the Z-line is the region of the I-band (for isotropic). I-band is the zone of thin filaments that is not superimposed by thick filaments (myosin).

- Following the I-band is the A-band (for anisotropic). Named for their properties under a polarizing microscope. An A-band contains the entire length of a single thick filament. The Anisotropic band contains both thick and thin filaments.

- Within the A-band is a paler region called the H-zone (from the German "heller", brighter). Named for their lighter appearance under a polarization microscope. H-band is the zone of the thick filaments that has no actin.

- Within the H-zone is a thin M-line (from the German "Mittelscheibe", the disc in the middle of the sarcomere) formed of cross-connecting elements of the cytoskeleton.

The relationship between the proteins and the regions of the sarcomere are as follows:

- Actin filaments, the thin filaments, are the major component of the I-band and extend into the A-band.

- Myosin filaments, the thick filaments, are bipolar and extend throughout the A-band. They are cross-linked at the centre by the M-band.

- The giant protein titin (connectin) extends from the Z-line of the sarcomere, where it binds to the thick filament (myosin) system, to the M-band, where it is thought to interact with the thick filaments. Titin (and its splice isoforms) is the biggest single highly elasticated protein found in nature. It provides binding sites for numerous proteins and is thought to play an important role as sarcomeric ruler and as blueprint for the assembly of the sarcomere.

- Another giant protein, nebulin, is hypothesised to extend along the thin filaments and the entire I-Band. Similar to titin, it is thought to act as a molecular ruler along for thin filament assembly.

- Several proteins important for the stability of the sarcomeric structure are found in the Z-line as well as in the M-band of the sarcomere.

- Actin filaments and titin molecules are cross-linked in the Z-disc via the Z-line protein alpha-actinin.

- The M-band proteins myomesin as well as C-protein crosslink the thick filament system (myosins) and the M-band part of titin (the elastic filaments).

- The M-line also binds creatine kinase, which facilitates the reaction of ADP and phosphocreatine into ATP and creatine.

- The interaction between actin and myosin filaments in the A-band of the sarcomere is responsible for the muscle contraction (sliding filament model).[1]

Contraction

The protein tropomyosin covers the myosin-binding sites of the actin molecules in the muscle cell. For a muscle cell to contract, tropomyosin must be moved to uncover the binding sites on the actin. Calcium ions bind with troponin C molecules (which are dispersed throughout the tropomyosin protein) and alter the structure of the tropomyosin, forcing it to reveal the cross-bridge binding site on the actin.

The concentration of calcium within muscle cells is controlled by the sarcoplasmic reticulum, a unique form of endoplasmic reticulum in the sarcoplasm.

Muscle cells are stimulated when a motor neuron releases the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, which travels across the neuromuscular junction (the synapse between the terminal bouton of the neuron and the muscle cell). Acetylcholine binds to a post-synaptic nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. A change in the receptor conformation allows an influx of sodium ions and initiation of a post-synaptic action potential. The action potential then travels along T-tubules (transverse tubules) until it reaches the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Here, the depolarized membrane activates voltage-gated L-type calcium channels, present in the plasma membrane. The L-type calcium channels are in close association with ryanodine receptors present on the sarcoplasmic reticulum. The inward flow of calcium from the L-type calcium channels activates ryanodine receptors to release calcium ions from the sarcoplasmic reticulum. This mechanism is called calcium-induced calcium release (CICR). It is not understood whether the physical opening of the L-type calcium channels or the presence of calcium causes the ryanodine receptors to open. The outflow of calcium allows the myosin heads access to the actin cross-bridge binding sites, permitting muscle contraction.[4]

Muscle contraction ends when calcium ions are pumped back into the sarcoplasmic reticulum, allowing the contractile apparatus and, thus, muscle cell to relax.

Upon muscle contraction, the A-bands do not change their length (1.85 micrometer in mammalian skeletal muscle),[4] whereas the I-bands and the H-zone shorten. This causes the Z lines to come closer together.

Rest

At rest, the myosin head is bound to an ATP molecule in a low-energy configuration and is unable to access the cross-bridge binding sites on the actin. However, the myosin head can hydrolyze ATP into adenosine diphosphate (ADP and an inorganic phosphate ion. A portion of the energy released in this reaction changes the shape of the myosin head and promotes it to a high-energy configuration. Through the process of binding to the actin, the myosin head releases ADP and an inorganic phosphate ion, changing its configuration back to one of low energy. The myosin remains attached to actin in a state known as rigor, until a new ATP binds the myosin head. This binding of ATP to myosin releases the actin by cross-bridge dissociation. The ATP-associated myosin is ready for another cycle, beginning with hydrolysis of the ATP.

The A-band is visible as dark transverse lines across myofibers; the I-band is visible as lightly staining transverse lines, and the Z-line is visible as dark lines separating sarcomeres at the light-microscope level.

Storage

Most muscle cells store enough ATP for only a small number of muscle contractions. While muscle cells also store glycogen, most of the energy required for contraction is derived from phosphagens. One such phosphagen, creatine phosphate, is used to provide ADP with a phosphate group for ATP synthesis in vertebrates.[4]

Comparative structure

The structure of the sarcomere affects its function in several ways. The overlap of actin and myosin gives rise to the length-tension curve, which shows how sarcomere force output decreases if the muscle is stretched so that fewer cross-bridges can form or compressed until actin filaments interfere with each other. Length of the actin and myosin filaments (taken together as sarcomere length) affects force and velocity – longer sarcomeres have more cross-bridges and thus more force, but have a reduced range of shortening. Vertebrates display a very limited range of sarcomere lengths, with roughly the same optimal length (length at peak length-tension) in all muscles of an individual as well as between species. Arthropods, however, show tremendous variation (over seven-fold) in sarcomere length, both between species and between muscles in a single individual. The reasons for the lack of substantial sarcomere variability in vertebrates is not fully known.

References

- Reece, Jane; Campbell, Neil (2002). Biology. San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 0-8053-6624-5.

- Assuming that the length of biceps is 20 cm and the length of sarcomere is 2 micrometer, there are 100,000 sarcomeres along the length of biceps.

- Martonosi, A. N. (2000-01-01). "Animal electricity, Ca2+ and muscle contraction. A brief history of muscle research". Acta Biochimica Polonica. 47 (3): 493–516. ISSN 0001-527X. PMID 11310955.

- Lieber (2002). Skeletal Muscle Structure, Function & Plasticity : The Physiological Basis of Rehabilitation (2nd ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0781730617.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sarcomeres. |

- MBInfo: Sarcomere

- MBInfo: Contractile Fiber

- Muscular Tissues Videos

- Histology image: 21601ooa – Histology Learning System at Boston University - "Ultrastructure of the Cell: sarcoplasm of skeletal muscle"

- MedicalMnemonics.com: 50 379 107

- Images created by antibody to striations

- Muscle Contraction for dummies

- Model representation of the sarcomere