Sand shiner

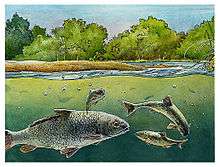

The sand shiner (Notropis stramineus) is a widespread North American species of freshwater fish in the family Cyprinidae.[2] Sand shiners live in open clear water streams with sandy bottoms where they feed in schools on aquatic and terrestrial insects, bottom ooze and diatoms.[3]

| Sand shiner | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Cypriniformes |

| Family: | Cyprinidae |

| Subfamily: | Leuciscinae |

| Genus: | Notropis |

| Species: | N. stramineus |

| Binomial name | |

| Notropis stramineus (Cope, 1865) | |

| Synonyms | |

Distribution

The sand shiner is extremely widespread, known from central part of the United States and southern Canada. The range stretches from Saint Lawrence-Great Lakes, Hudson Bay and Mississippi River basins which are part of the St. Lawrence River in Quebec to Saskatchewan in Canada. The range also stretches south to Tennessee and Texas; west to Montana, Wyoming, Colorado and New Mexico; Trinity River to Rio Grande in Texas and New Mexico, and Mexico.[4]

Name

The genus name Notropis means keeled back and specific epithet stramineus means of straw, making reference to the fish's overall pale amber body color.[5] Neotropis ludibundus is a senior synonym of N. stramineus, however, the specific name N. stramineus is conserved and N. ludibundus is suppressed.[6]

Physical characteristics

Sand shiners have a compressed, slender body covered in leptoid scales, more specifically cycloid scales which are generally round and lack a tooth-like cteni. They have a subterminal mouth position (the end of the snout projects only slightly past the mouth) and a homocercal tail (the vertebral column does not enter the caudal fin).[7] Sand Shiners usually have seven anal soft rays, fewer than 10 dorsal fin soft rays, and fewer than 45 lateral line scales.[4] They have no spinous rays meaning none of their rays are hard. Their pharyngeal teeth count is 0,4-4,0.[4] The average total length of a Sand Shiner is about 44 mm with a maximum length of approximately 82 mm.[5][8] They have a silvery head and sides with a dark middorsal strip extending to the dorsal fin.[9] At the base of the dorsal fin are two distinct black dashes separated by a clear space when viewed from above.[9] Their back scales are an olivaceous color and are outlined with melanophores.[9] Each pore within the lateral line system, is also accented with paired melanophores which creates the appearance of a thin midlateral strip.[4][9] The abdomen is a whitish color with indistinct spots at the base of the caudal fin. During spawning, colors intensify in males.[9]

Habitat

The sand shiner requires clear water with a sandy, gravel-rubble bottom in order to survive.[10][11] It is irregularly distributed amongst streams of diverse sizes and inhabits a wide variety of habitats within the medium to large streams and rivers but is rarely found in upland areas.[12] Sand Shiners tend to seek areas deeper than 20 cm which have little to no aquatic vegetation and a slow-moving current.[9] Habitats with acidic or alkaline conditions are avoided, however, in the Southwest, pH values of around 8.0 are common in streams which Sand Shiners occupy.[9] Habitat locations change slightly throughout the seasons. During spawning season in August, sand shiners form large schools in shallow water which has a slight current and a sandy bottom. In the fall, concentrations of sand shiners are found in deep pools. In late summer and fall, the sand shiners tend to move into shallow water over a rubble bottom during dusk.[13][14]

Diet and feeding behavior

Sand shiners are omnivorous fish, feeding on aquatic and terrestrial insects, bottom ooze and diatoms and are often observed in large schools which frequently feeding in shallow waters.[3] Overall, this species is an opportunistic feeder primarily taking bottom particulate matter, as well as plant material and terrestrial and aquatic insects.[9] More explicitly, their summer diet consists of bottom ooze (68% of volume), aquatic nymphs and larvae, Ephemeroptera nymphs, Tricoptera larvae, adult terrestrial insects, adult and emerging Ephemeroptera, dipterans, corixids, and a small amount of plant matter.[13][15] During late summer, sand shiners show more surface-oriented feeding behaviors, feeding on adult aquatic and terrestrial insects.[16] These feeding habits are similar to the closely related Cape Fear shiner and swallowtail shiner.

Conservation status

Populations of sand shiners in the southern United States are currently stable. They are not listed as endangered by the federal government or any state governments.[17] The state of New Mexico provides limited protection as precipitous decline in Pecos River may becoming a potential threat. This decline is partially as a consequence of water management practices.[11][18]

Reproduction

The total reproductive period of sand shiners extends from May or June through August with slight variation in time of spawning depending upon latitude.[9][12] The peak of activity occurs in July and August when water temperature is high (27- 37°C ) and there is minimal rain and runoff allowing for lower water levels.[19][11] Summerfelt and Minckley hypothesis spawning during the hot-dry portion of the summer is adaptive for survival as it may enhance the survival of the young.[19] The sand shiner is a broadcast spawner that lays demersal, adhesive eggs, suggesting that the sand shiners spawning is not correlated with flow spikes.[11] Eggs are laid in shallow water over sandy substrate in which the eggs rapidly settle to and attach to loose gravel, failing to become buoyant.[9][11] Following hatching, most growth is achieved during the first year of life. A length of 10.5 mm has been reported for the size of the sand shiner at time of scale formation.[19] Once fish reach age I or II, spawning can occur with the former being more numerous.[19] Fecundity varies from 150-1,000 eggs per female per year.[5] There is an increase in fecundity with standard length (or age) of the fish.[10] Egg diameter ranges from 0.75-0.95 mm.[20] On average, the sand shiner has a longevity of three summers.[19][10]

References

- NatureServe (2016). "Notropis stramineus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2013). "Notropis stramineus" in FishBase. April 2013 version.

- Koster, W. J. 1957. Guide to the Fishes of New Mexico. Univ. New Mexico Press, Albuquerque."Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-09-10. Retrieved 2011-05-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Hubbs, C., R. J. Edwards, and G. P. Garrett. 1991. An annotated checklist of the freshwater fishes of Texas, with keys to identification of species. Texas Journal of Science, Supplement 43(4):1-56

- Etnier, D. A., and W. C. Starnes. 1993. The Fishes of Tennessee. University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville, 681 pp."Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-09-10. Retrieved 2011-05-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Mayden, R. L. and C. R. Gilbert. 1989. Notropis ludibundus (Girard) and Notropis tristis (Girard), replacement names for N. stramineus (Cope) and N. topeka (Gilbert) (Teleostei: Cypriniformes). Copeia 1989(4):1084-1089.

- Page, L. M., and B. M. Burr. 1991. A Field Guide to Freshwater Fishes of North America, north of Mexico. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 432 pp. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-09-10. Retrieved 2011-05-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Hugg, D.O. 1996 MAPFISH georeferenced mapping database. Freshwater and estuarine fishes of North America. Life Science Software. Dennis O. and Steven Hugg, 1278 Turkey Point Road, Edgewater, Maryland, USA.

- Sublette, J. E., M. D. Hatch, and M. Sublette. 1990. The Fishes of New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 393 pp "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-09-10. Retrieved 2011-05-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Tanyolac, J. 1973. Morphometric variation and life history of the cyprinid fish Notropis stramineus (Cope). Occ. Pap. Mus. Nat. Hist. Univ. Kans. 12:1-28."Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-09-10. Retrieved 2011-05-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Platania, S. P. and C. S. Altenbach. 1998. Reproductive strategies and egg types of seven Rio Grande Basin cyprinids. Copeia 1998(3):559-569.

- Lee, D. S., Gilbert C. R., Hocutt C. H., Jenkins R. E., Callister D. E., and Stauffer J. R. 1981. Atlas of North American Freshwater Fishes: North Carolina, North Carolina State Museum of Natural History, 1981, c1980

- Starett, W. C. 1950a. Distribution of the fishes of Boone County, Iowa, with special reference to the minnows and darters. American Midland Naturalist 43(1):112-127.

- Mendelson, J. 1975. Feeding relationships among species of Notropis (Pisces: Cyprinidae) in a Wisconsin stream. Ecol. Monogr. 45:199-230.

- Becker, G. C. 1983. Fishes of Wisconsin. The University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, 1052 pp.

- Gillen, Alan L. and Thomas Hart. 1989. Feeding Interrelationships Between the Sand Shiner and the Striped Shiner. Ohio J. Science, Ohio 71-76.

- Warren, L. W., Jr., B. M. Burr, S. J. Walsh, H. L. Bart, Jr., R. C. Cashner, D. A. Etnier, B. J. Freeman, B. R. Kuhajda, R. L. Mayden, H. W. Robison, S. T. Ross, and W. C. Starnes. 2000. Diversity, Distribution, and Conservation status of the native freshwater fishes of the southern United States. Fisheries 25(10):7-29.

- Matthews, W.J. 1987. Geographic variation Cyprinella lutrensis (Pices: Cyprinidae) in the United States, with notes on Cyprinella lepida. Copeia 1979: 70-81.

- Summerfelt, R. C., and C. O. Minckley. 1969. Aspects of the life history of the sand shiner, Notropis stramineus (Cope), in the Smokey Hill River, Kansas. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 3:444-453.

- Coburn, M. M. 1986. Egg diameter variation in Eastern North American minnows (Pisces: Cyprinidae): correlation with vertebral number, habitat, and spawning behavior. Ohio Journal of Science 86(3):110-120

- Robert Jay Goldstein, Rodney W. Harper, Richard Edwards: American Aquarium Fishes. Texas A&M University Press 2000, ISBN 978-0-89096-880-2, p. 94 (restricted online copy, p. 94, at Google Books)

- "Sand Shiner (Notropis stramineus)". Inland Fishes of New York. Retrieved 2007-12-10.