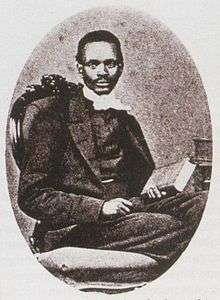

Tiyo Soga

Tiyo Soga (1829 – 12 August 1871) was a South African journalist, minister, translator, missionary evangelist, and composer of hymns. Soga was the first black South African to be ordained and worked to translate the Bible and John Bunyan's classic work Pilgrim's Progress into his native Xhosa language.[1]

Background

Soga was Xhosa.[2] When his mother Nosuthu became a Christian she sought and received release from her marriage to Jotello, a head advisor of Chief Ngqika, on the grounds that she wanted her son to be raised a Christian and receive formal education. Nosuthu's request was granted and she took Soga to the Chumie Mission. As a child in Chumie, Soga attended the school of the Rev. John A. Chalmers.[3]

In 1844 at the age of 15 Soga received a scholarship to Lovedale Missionary Institution located 13 kilometres (8.1 mi) from Chumie. Soga's education was interrupted by the "War of the Axe" in 1846 and he and his mother were forced to take refuge in nearby Fort Armstrong.[3] The principal of Lovedale, Rev. William Govan, decided to return home to Scotland and offered to pay the way for Soga to come with him and seek higher education. Nosuthu agreed to let her son go. Not knowing if she would ever see him again, she said: "my son belongs to God; wherever he goes God is with him…he is as much in God's care in Scotland as he is here with me". [4]

Soga attended the Normal School in Glasgow, Scotland and was "adopted" by the John Street United Presbyterian Church. During his stay in Scotland Soga made a formal profession of Christian faith and was baptized in May 1848.[3] During his time in Scotland Soga developed a sympathetic perspective for both the white and black races and his unique racial perspective remained with him for the rest of his life.

After two years in Scotland, Soga returned to the Eastern Cape to work as an evangelist and teacher in Chumie. Soga was asked by the Rev. Robert Niven to help establish a new mission station in the Amatole Mountains and he faithfully planted the Uniondale Mission in Keiskammahoek. Because of its identification with the colonial authorities Uniondale mission was burnt to the ground by those at war with the colonial powers. Soga was almost killed in the incident and refused to side with the chief leading the war or to accept the position of translator offered him by the colonial government.

Soga decided to pursue further theological education and accompanied Rev. Niven back to Scotland where he enrolled at the Theological Hall, Glasgow so that he might "learn better how to preach Christ as my known Saviour to my countrymen who know Him not".[5] On 10 December 1856 Tiyo Soga became the first black South African to be ordained in the United Presbyterian Church.[6] Two months after his ordination Soga married Janet Burnside, a Scotswoman who was "a most honourable, thrifty, frugal, and devoted woman who marched heroically and faithfully by her husband's side through all the chequered scenes of his short life". Throughout his life Soga faced racism as a "Kaffir" and was treated as a second-class citizen by many whites in Africa. Soga also faced opposition from black Africans, some of whom thought of him as trying to become a "black Englishman".[3]

In 1857 Soga returned to the Eastern Cape with his wife where they eventually founded the Emgwali Mission where Soga worked among his native Ngqika people. During their years in Emgwali the Soga's had seven children. His fourth son was Jotello Festiri Soga, the first black veterinary surgeon in South Africa.[7] Janet Soga returned to England for the births of all her children. Tiyo Soga suffered from poor health and it was during one of these bouts of sickness that he used his time to translate Pilgrim's Progress (U-Hambo Iom-Hambi) into his native Xhosa language. Soga's translation and adaptation of Pilgrim's Progress has been called "the most important literary influence in 19th century South Africa after the Bible."[6] He also worked to translate the Christian gospels and served on the advisory board to revise the Xhosa Bible.[3]

At the end of his short life Soga was sent to open a new mission station in Tutuka (Somerville) in Kreli's country and the difficult work further deteriorated his health.[1] It was the desire of Soga that his children be educated in Scotland and before his death instructed his sons, "For your own sakes never appear ashamed that your father was a "Kaffir" and that you inherit some African blood. It is every whit as good and as pure as that which flows in the veins of my fairer brethren…you will ever cherish the memory of your mother as that of an upright, conscientious, thrifty, Christian Scots woman. You will ever be thankful for your connection by this tie with the white race".[8]

Soga died of tuberculosis in August 1871. He died in the arms of fellow missionary Richard Ross with his mother, Nosuthu, by his side. He is considered by many to be the first major modern African intellectual and was among the first Christian leaders to assert the right of black Africans to have freedom and equality.[6]

Hymns and poetry

One of Soga's hymns exemplifies his Xhosa heritage by setting the words of Ntsikana's "Great Hymn" to music. Ntsikana, a Xhosa chief, is remembered as the first important African convert to Christianity. Around 1815, Ntsikana started the first African Christian organization and went on to write four poetic hymns. His "Great Hymn" extols God as creator and redeemer, and still appears with Soga's music in modern hymnbooks.[9]

Although Ntisikana died before Soga's birth, Soga was clearly influenced by his predecessor's poetry and example.[10] Soga's tribute to Ntsikana includes the lines:

What "thing" Ntsikana, was't that prompted thee

To preach to thy dark countrymen beneath yon tree'?

What sacred vision did the mind enthral,

Whil'st thou lay dormant in thy cattle kraal?[9]

Soga's "Bell Hymn", used to call worshippers together, is also based on a Ntisikana poem. African poet and playwright H. I. E. Dhlomo's play The Girl Who Killed to Save: Nongqause the Liberator incorporates the music of the Bell Hymn.[11]

The character of Soga himself appears at the end of the play, heralded by other characters singing another of Soga's hymns, "Fulfill Your Promise." Lizalis' idinga lakho[12] This hymn was sung long after Soga's death, to open the first meeting of the South African Native National Congress in 1912.[12] "Fulfill Your Promise" may also have inspired the African National Congress anthem, "God Bless Africa". Soga wrote the hymn in July 1857, when he returned to Africa. The last verse of "Fulfill Your Promise" may be translated as:

O Lord, bless

The teachings of our land;

Please revive us

That we may restore goodness.[12]

References

- "Missionaries, South Africa". Genealogy World. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- "Tiyo Soga | South African author". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- "Soga, Tiyo". Dictionary of African Christian Biography (DACB). Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- McGregor, A. (1978). "Missionary women". Annals of the Grahamstown Historical Society. 2 (4): 180.

- Chalmers, John A. (1878). Tiyo Soga: a page of South African Mission Work (2nd ed.). Grahamstown: James Hay.

- "Soga, Tiyo". South African Presidential Website. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- Tiyo Soga (1983). The journal and selected writings of the Reverend Tiyo Soga. Grahamstown: Rhodes University. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-86961-148-7 – via A.A. Balkema.

- Cousins, H.T. (1899). From Kaffir Kraal to Pulpit: The Story of Tiyo Soga. London: S.W. Partridge.

- "Ntsikana". Dictionary of African Christian Biography (DACB) This article is reproduced, with permission, from Malihambe - Let the Word Spread, copyright © 1999, by J. A. Millard, Unisa Press, Pretoria, South Africa. All rights reserved. Archived from the original on 7 June 2017. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- Duncan, Graham A. (2018). "Tiyo Soga (1829–1871) at the intersection of 'universes in collision'". HTS Teologiese Studies / Theological Studies. 74 (1). doi:10.4102/hts.v74i1.4862. ISSN 2072-8050.

- Wentzel, Jennifer (Spring 2005). "Voices of Spectral and Textual Ancestors: Reading Tiyo Soga alongside H. I. E. Dhlomo's The Girl Who Killed to Save". Research in African Literatures. Indiana University Press. 36 (1): 51–73. JSTOR 3821319.

- "Music of the play as means to bring the past alive". Universität Wien. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2011.