Saitō Satoshi

Saitō Satoshi (齋藤 聰, March 24, 1922 – March 16, 2014)[1] was the 5th generation Sōke of Negishi-ryū, a classical Japanese warrior tradition and the nation's last surviving specialist school of Shurikenjutsu.[2] From 1997 to 2014 (17 years), Saitō served as the elected Chairman of the Nihon Kobudō Shinkōkai (est. 1935), Japan's oldest classical martial arts association.[3] In addition, Saitō was the 6th generation head of Shirai-ryū shurikenjutsu and the 15th Sōke of Kuwana Han-den Yamamoto-ryū Iaijutsu. In 1992, Saitō was awarded the Imperial Order of the Sacred Treasure.[4]

| Saitō Satoshi | |

|---|---|

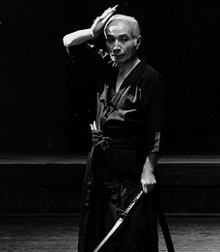

Saitō Satoshi, 5th Sōke of Negishi-ryū | |

| Born | March 24, 1922 Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan |

| Died | March 16, 2014 (aged 91) Itabashi-ku, Tokyo, Japan |

| Native name | 齋藤 聰 |

| Style | Negishi-ryū Shurikenjutsu Shirai-ryū Shurikenjutsu Kuwana Han-den Yamamoto-ryū Iaijutsu |

| Teacher(s) | Gichin Funakoshi Kanji Naruse Seiko Fujita |

| Rank | Sōke / Headmaster |

Biography

Born in Tokyo’s Minato Ward on March 24, 1922, Saitō Satoshi was one of four siblings. At the age of eighteen he enrolled at the law faculty of Tokyo's Keio University.[5] Whilst at Keio, he began the study of karate under Funakoshi Gichin, the attributed father of modern-day karate-dō.[6] In 1941, at the age of 19, Saitō began his training in shurikenjutsu under the instruction of Naruse Kanji, headmaster of the Negishi-ryū tradition. In 1943, Saitō was drafted into the military. When Naruse heard that Saitō would be heading off to war, he had the blade of his most treasured katana fitted to the body of a military issued guntō. Saitō was instructed to carry it bravely into battle. During his service, Saitō attained the rank of second lieutenant, receiving training as both an artillery officer and an aircraft navigator.[7] During his military service, he made regular visits to the dōjō of Miyawaki Tōru, master of Chuya-ha Itto-ryū and Shirai-ryū Shurikenjutsu. For many years, Naruse had been working toward the resurrection of Shirai-ryū, which many believed to have died-out. At Naruse's request, Saitō compiled valuable technical and historical information concerning the tradition. Eventually however, both Miyawaki and his Shizuoka-based dōjō fell victim to a strategic bombing campaign, which had been targeting the armament factories and airfields in Hamamatsu.[8] During this period, Naruse Kanji had written to Saitō Satoshi and expressed his wish for him to succeed him as headmaster of both the Negishi-ryū and Yamamoto-ryū traditions.

After the war drew to a close in late 1945, Saitō returned to studies at Keio University. He supported himself financially by working several part-time jobs. Nuruse’s health was deteriorating by this stage, but Saitō paid regular visits leading up to his death. Professionally, Saitō worked as a civil servant for the city of Tokyo. He served at various ministries, and specialized in the field of statistics. He also worked as Chief-of-Staff at Tokyo Metropolitan University and lectured at the Faculty of Economics. He was also a senior adviser to the National Federation of Statistical Associations in Japan. In 1983, he received the Ouchi Prize, in honor of his contribution to the field of statistics.[9] For seventy years, Saitō Satoshi had been a devoted researcher and collector of all things related to Japan’s militaristic past. His personal collection of weapons, books, scrolls, historical documents and antiques was overwhelmingly extensive. In 1949, Saitō became a friend and student of Fujita Seiko, commonly known as the last Kōga Ninja.[10] In 1954, Saitō Satoshi brought Negishi-ryū back to the public eye when he demonstrated the art at the first postwar Japanese Martial Arts Exposition, held at the Tokyo Taikukan in Sendagaya ward. The aftermath of World War 2 and the subsequent banning of all martial arts by the Allied Occupation Forces meant that many classical martial arts were now facing possible extinction. This monumental event, which was sponsored by the Life Extension Society, is said to have attracted an audience of over 15,000. It was at this event that Saitō Satoshi first met and became friends with Gōzō Shioda, founder of the Yōshinkan School of Aikidō. Between the years of 1957 and 1994, Saitō made regular TV appearances on NHK, TBS (Japan), TV Asahi, TV Tokyo and Tokai TV. He was also called upon to choreograph fight scenes for period dramas and films. During this period, Saitō became friends with Nawa Yumio of the Masaki-ryū, and later instructed him in the art of shurikenjutsu (Nawa had also studied under Maeda Isamu, 4th generation Sōke of Negishi-ryū). In 1992, Saitō Satoshi was awarded the Imperial Order of the Sacred Treasure. After his retirement, Saitō dedicated his life exclusively to the study and preservation of classical Japanese warrior traditions. From 1997 until his death in 2014, he served as Chairman (会長) of the Nihon Kobudō Shinkōkai (日本古武道振興会), Japan’s oldest and most illustrious kobudo organisation (est. 1935). He was also a long-term Director of the Nihon Kobudō Kyōkai (日本古武道協会). On 16 March 2014, Saitō Satoshi attended a plum-blossom festival with one of his senior students, David Kawazu-Barber, head of the Kamakura branch. After returning home that same evening, he passed away peacefully in his sleep; his death was attributed to old-age.

Negishi-ryū Shurikenjutsu

The Negishi school of shurikenjutsu is a classical Japanese martial art (Koryū) founded by samurai, Negishi Shōrei in the mid 1850s. Its distant roots can be traced back to the Sendai region's Katori Shinkon-ryū (divine soul school), an offshoot of Tenshin Shōden Katori Shintō-ryū (divine way school) originating in Chiba prefecture, Japan. A master of the Katori Shinkon-ryū, Matsubayashi Samanotsuke Nagayoshi, aka "Henyasai" (the bat), later founded his own school of sōgō bujutsu in 1644 and named it Ganritsu-ryū. Ganritsu-ryū spread throughout the Tohoku region, and was handed down within the Katōno family for generations. Date Yoshikuni, 13th generation lord of the Sendai domain, received the art from the Katōnos. Due to their light weight and concealability, Lord Date insisted that women within his household be trained in the art, as a method of self-defense. Date's wife, Tokugawa Takako, daughter of Tokugawa Nariaki (aka, Mito Rekko), Lord of the Mito territory, developed a high level of skill in the art. At her father's request, Takako passed the art on to Kaiho Hanpei, the official sword instructor for the Mito territory. As a child, Kaiho Hanpei enrolled as a disciple of Negishi Tsunemasa, master of Araki-ryū in the Annaka Domain. After Tsunemasa’s death, he continued his studies under his son, Negishi Sentoku, the 3rd generation master of the school. In 1849, Negishi Sentoku asked Kaiho to instruct his 16-year-old son, Shōrei, in the arts of Hokushin Ittō-ryū and Ganritsu-ryū. Within a few years, Negishi Nobunori Shōrei became Kaiho’s most skilled student. Having perfected and refined his skill in shuriken-jutsu, Shōrei felt the need to develop a new breed of shuriken-jutsu. His aim was to create a school that focused exclusively on shuriken combat. This gave birth to Negishi-ryū. The school uses the jiki-dahō (direct flight) throwing method (unique to Japan) and incorporates the use of weapons, such as the sword.[11]

Shirai-ryū Shurikenjutsu

The Shirai school of shurikenjutsu is a classical Japanese martial art (koryū) founded by samurai, Shirai Tōru in the early 1800s. The school uses long, needle-like darts, which can be thrown using the jiki-dahō (direct flight) or hanten-dahō (half-spin) methods. Used in conjunction with weapons, such as the sword and shubō, Shirai-ryū shurikenjutsu is a powerful and devastating system of traditional Japanese combat.[12]

Kuwana Han-den Yamamoto-ryū Iaijutsu

Handed down within the Naruse family for generations, Yamamoto-ryū Iaijutsu was founded by Yamamoto Jikensai, brother of Yamamoto Kansuke. The school consists largely of iaijutsu, as the name suggests, but also includes a short kenjutsu & jujutsu curriculum.

Shingetsu-ryū Shurikenjutsu / Kōga-ryū Tradition

Training under the guidance of Fujita Seiko from 1949 onward, Saito Satoshi received instruction in Shingetsu-ryū Shurikenjutsu.[13]

Honors

- Imperial Order of the Sacred Treasure (Japan), 1992.

- Honorable Chairman, Nihon Kobudō Shinkōkai (Japan Kobudo Promotion Society), 1997-2014.

- Director, Nihon Kobudō Kyōkai (Japan Kobudō Association).

Legacy

During his lifetime, Saito Satoshi only accepted a small number of students, which he trained privately at his home dojo in Tokyo. Only four were awarded teaching licenses.[14]

Major Publications

- Nihon Budō Zenshū Vol.6 -Shurikenjutsu (1967),Shin Jinbutsu Ōraisha, ISIN: B000JB7T9K

- Nihon Budō Taikai Vol.7 -Shurikenjutsu (1982), Dōhōsha, ISIN: B000J7H2S2

- Nihon no Budō Vol.11 -Shurikenjutsu (1983), Kodansha, ISBN 4061880918

- Nihon Denshō Bugei Ryūha Dokuhon Negishi-ryū Shurikenjutsu, 1994),Shin Jinbutsu Ōraisha, ISBN 4883173259

References

- Official statement from Nihon Kobudō Shinkōkai, released April 2014

- Kobudo Renbukan website

- Official statement from Nihon Kobudō Shinkōkai, released April 2014

- Nippon Budokan Foundation Report, March 2007

- Published profile in International Seminar of Budo Culture booklet, Nippon Budokan Foundation 2007.

- Interview with Miek Skoss, Sword & Spirit, Classical Warrior Traditions of Japan, Vol.2, ISBN 1-890536-05-9

- Interview with Miek Skoss, Sword & Spirit, Classical Warrior Traditions of Japan, Vol.2, ISBN 1-890536-05-9

- Interview with David Kawazu-Barber, Fighters Magazine 2012.

- Published profile in International Seminar of Budo Culture booklet, Nippon Budokan Foundation 2007

- Article by David Kawazu-Barber published in 2nd edition, Fujita Seiko, The Last Koga Ninja.

- Nihon Kobudō Kyōkai

- Nihon Kobudō Shinkōkai Diamond Jubilee Publication, 2010.

- Interviews with David Kawazu-Barber, conducted by Phillip Hevener 2009-2014.

- Nippon Budokan Foundation's "Budo" magazine, Jan. 2014.