Saint-Étienne Mine Museum

The Saint-Étienne Mine Museum is a French museum founded in 1991 in the city of Saint-Étienne in the French department of the Loire situated in the Rhône-Alpes region. The site is registered as a historical monument since 2011.[1]

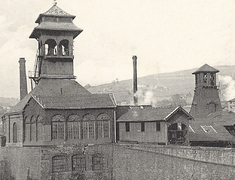

Couriot pit Headframe. | |

| |

| Established | 1991 |

|---|---|

| Location | 3, boulevard Franchet d'Espèrey, Saint-Étienne, Rhône-Alpes, France |

| Coordinates | 45.438514°N 4.376636°E |

| Type | Show Mine |

| Collections | Mining 15 hectares (37 acres) |

| Visitors | 50,000–60,000 visitors/year |

| Website | www |

Presentation

Officially named Puits Couriot ([pɥi kuʁjo]; English: Couriot Coalmine) / Parc Musée de la Mine ([paʁk myze də la min]; English: Mine Museum Park), it is set up in the buildings of the last coal pit of the city (closed in 1973).

The museum is also a show mine and thus offers the possibility to visit a reconstructed gallery and the historical buildings of the former mine site:

- the Grand lavabo (the main washroom);

- the hoist room and the power room (superchargers and electric converters);

- the lamp room (lamp maintenance workshop);

- the compressor room;

- the electric locomotives maintenance shop;

- former access to underground structures (tunnel of the Loire pit, slotted bridges).

The museum also offers three permanent exhibition tours (launched in December 2014). Those exhibitions display a selection of objects from the museum's collections:

- The Figure of the Miner (reproduction of "Mineurs" by Jean-Paul Laurens, Le Mineur by Armand Bloch, sculptures, posters, extracts from archive films);

- The Great History of Couriot (tactile model, animated theater, cut view of the Couriot pit, relief maps and cut views of Mines de la Loire plc)'s mines.

- Six Centuries of Coal Adventures (large relief plan of the Loire area created for the Universal Exhibition of 1889, video wall, models, posters, photographs, tools and everyday objects among others ...).

The site is also part of a cultural program (performing arts, film screenings, festivals). It was awarded the Musée de France label.

Above-ground facilities

The Couriot pit site covers an area of 115 hectares (37 acres) if the slag heaps are included). It is the best preserved remnant and the most comprehensive showing of the coal activity of the area.

The facilities situated above ground responded to the need to circulate men, coal and equipment in the same limited space. In order to manage traffic flow near the pit, the site was organized under a system of platforms where former quarries used to be.

Washing rooms and sorting plants were installed on the lower platform called the "plâtre"(the plaster) and were demolished in 1969.

For the most part, the buildings of the intermediary platform, which have been preserved, date back to the First World War (administrative buildings, boiler room, former lamp room, engine room and the "petit lavabo" (the small washroom)) and to the post-war era ("grand lavabo" and lamp room of 1948).

In its most recent configuration, the pit could accommodate nearly 2,000 miners and several hundred workers every day.

The site was the head office of the Société Anonyme des Mines de la Loire. It was the largest pit of the area until the 1930s and remained the western sector headquarters after the 1946 nationalisation .

Site history

Located west of Saint-Étienne, the site is located within the perimeter of the old town of Montaud, then split with the ephemeral town of Beaubrun (1842–1855) which is finally integrated in Saint-Étienne in 1855. Certified since the 18th century, coal mining in this area is due to the presence of an anticline bringing three shallow exploitable layers to the surface (the first, second and third layers of the Beaubrun part of the pit). The rugged terrain of the area of the old locality known as the Clapier reflects the previous exploitation of the outcrops of these coal layers. These old quarries have also provided the sandstone needed to create underground work (called overturned bleachers) until the 1930s.

Around 1810, the activity seemed restricted when compared to Villars', east of Saint-Étienne (beyond the Furan) in Saint-Jean-Bonnefonds and especially the Gier Valley which then produces nearly half of the domestic coal production. At that time, the area of Beaubrun is known in the official documents to be partly exploited and its former works, which sometimes resulted in deadly floods, made it difficult to exploit.

The 1840s Beaubrun plot

It was around 1840, with the development of the first railway junction from Saint-Étienne to Montrambert, that mining activity has sustainably grown in this sector. The Beaubrun plot was run by three small companies:

In the south, the Compagnie des Mines Ranchon: Mining company bordering the Tardy neighbourhood (now rue Vaillant Couturier). It owned a pit and a split.

To the west, the Compagnie Parisienne is a smaller company (two new pits which were then in the process of being dug).

In the southwest, near the present location of the Couriot pit, the Mines Grangette; grouping the pits Basses-villes 1 and 2 , Hautes-villes 1 and 2, Culatte 1 and 2 and Clapier 1 and 2 (scene of a disaster in 1839 which provoked a flood and its subsequent desertion for several decades) . The current location of the Couriot pit was then occupied by the Clapier castle.

This small company subsequently joined other companies to found the Compagnie des Houillères de Saint-Étienne in 1845 in order to counteract the irresistible rise of the Compagnie Générale des Mines de la Loire after a merger between various companies from Rive-de-Gier.

The CHSE was eventually absorbed in September 1845 by the great Compagnie Générale des Mines de la Loire.

1854–92: The Beaubrun Company

In 1854 Napoleon III dissolved the monopoly. A small company, the Compagnie des Mines Beaubrun ran the plot consisting of half a dozen old pits, among which the Châtelus pit (founded in 1850 by the Compagnie des Mines de la Loire). It is the result of the two great neighboring companies running two coal veins situated on each sides of the Malacussy underground rift which cuts the plot in two.

Its capital is partly owned by these powerful neighbors: The S.A. des Mines de la Loire which runs more concessions to the North and the Société Anonyme des Mines de Montrambert and la Béraudière in the South. Both societies were the result of the division of the monopoly and each owned a portion of the capital of the Beaubrun Company.

In 1857, Clapier Station was inaugurated and the rail workaround of the western part of Saint-Étienne provided new uses for the coal extracted in Beaubrun. A key element that would later make the site the main place of extraction.

Around 1860, the old Clapier castle was demolished along with the hamlet of Clapier. The Châtelus pit was connected to the old Clapier pit and 5th layer was explored but the digging of a new pit was required. The digging of a new pit named Châtelus 2 started in 1870.

In 1887, a huge explosion of coal dust in the area between Châtelus 1 and Culatte caused the death of 79 miners. The event made the headlines, the emotion was great and the damage was substantial: the pit was therefore closed.

On 3 June 1893, the small company was eventually absorbed by the Mines de la Loire, under the influence of Henry Couriot who probably saw development opportunities in the plot strategic position and stocks.

The new head office of the S.A. des Mines de la Loire

After the dissolution of the Compagnie des Mines de la Loire by Napoleon III in 1854, the S.A. des Mines de la Loire inherited the CML name, its debts and its Northwest plots.

1892–1893: it assimilated the Beaubrun Company and started working again (restarting Châtelus and modernising the sorting plants).

The company began in 1907 to design a new generation pit named Châtelus 3, which later became known as the Couriot pit. The pit was created to mine a vein of coal destined for coke named the "8th Grüner", the company hoped to reach a record depth of 1 km.

The Mines de la Loire associated themselves in 1911 with other partners to launch a housing project called La Ruche Immobilière(the property beehive) in order to house the workforce that would be working in their new pit.

The drilling ended at 727.25 m in 1914 and the headframe was skidded over the pit, but the beginning of World War I stopped the building work.

In 1917, the Châtelus 3 pit is renamed after the president of the Société Anonyme des Mines de la Loire, Henry Couriot and officially becomes the Couriot pit

1919: Couriot pit starts running. Within the pit, the wagon loading area is situated at −116 m below sea level (i.e. 643 m deep).

Meanwhile, the Mines de la Loire bought the surrounding land to prevent the urban sprawl of Saint Etienne, that is to say 5 km² of land that from then on limited the development of the western sector of the city.

1928: installation of a new concrete headframe for Châtelus 1 which became a service pit, the Chatelus 2 pit is deserted and backfilled.

March 1941: visit and speech of Marshal Philippe Pétain.

1946–1973: From Nationalisation to Closure

- 1945–1947: The project to make an extraction pit equipped with "skips" of Châtelus 1 is considered but there was no follow-up.

- October 1948: Miners go on strike, the mobile guard occupies the site. The same year, the installation of a new line of skips on the surface will allow the elevation of a second slag heap.

- 1969: Controlled caving of the concrete headframe of the Châtelus 1 pit.

- 1971: Couriot pit is progressively being shut down.

- 5 April 1973 : Couriot pit closure. The cables are cut. The last team to go down the pit to shut down the pumps got back above ground through the Rochefort pit. At that time, Couriot is the last pit to cease its activities in the city of Saint-Étienne.

Conversion of the pit after its closure

- 1991: Opening of the mining museum.

- The entire site was listed as historical monument in January 2011[1]

- 2013: Finalisation of the first phase of the conversion of the former "plâtre" (plaster) into a city park named after Joseph Sanguedolce.

- December 2014: Inauguration of three new exhibition spaces presenting a part of the museum's collections.

- Site entrance.

- The "Grand Lavabo" (the big sink) aka. The Hangmen Room.

- Administrative building.

- Emergency winding engine building.

- Main winding engine building.

- The winding engine.

- The power room.

Notes and references

- Listed as historical monument under the French Ministry of Culture's Base Mérimée (Mérimée Database) http://www.culture.gouv.fr/public/mistral/merimee_fr?ACTION=CHERCHER&FIELD_1=REF&VALUE_1=PA42000039

See also

Bibliography

- Couriot, album, coll. Heritage Loire basin 1, Mining Museum of Saint-Étienne (publishing city of Saint-Étienne), 2002.

- 100 sites in issues, Industrial heritage of Saint-Étienne and its territory, coll. Heritage of the Loire basin No. 2 Mining Museum of Saint-Étienne (publishing city of Saint-Étienne), 2006.

- Mr. Bedoin, The Etienne Mining Heritage Drive Guide Roche-La-Molière, 1985.

- Sagnard Jerome Joseph Berthet, minor Memories in Etienne basin, Alan Sutton Publishing, 2004, 128 p.

- Sagnard Jerome Joseph Berthet, Patrick Etievant, Wells coal from the Loire basin, Editions Alan Sutton, minors Memoirs, 2008, 128 p.

Related articles

The few headframes preserved in the area

- Combes Pit

- Marais pit

Other pits

- Pigeot pit

- Verpilleux pit