Safavid Campaign (1554–55)

The Safavid Campaign of 1554–55 was the final bout of hostilities between the Ottomans and the Safavids during the Ottoman-Safavid War of 1532–55. It was launched by Suleiman the Magnificent (r. 1520–66), and took place between June 1554 and May 1555.[1] It was part of the wider Sunni–Shia conflict.[2][3]

| Safavid Campaign (1554–55) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Ottoman–Safavid War (1532–55) | |||||||

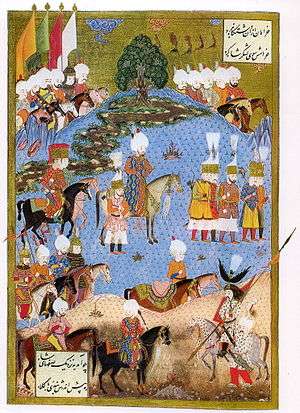

Miniature from the Süleymanname depicting Suleiman marching into Nakhchivan in the summer of 1554. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Sultan Suleiman Sokollu Mehmed Pasha | Shah Tahmasp I | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

Sultan's Army Rumelian forces | |||||||

Background

The campaign was triggered by the 1550–52 Safavid attacks in eastern Anatolia which devastated Van and Erzurum, and left many Sunnis dead.[3] In a letter dated July 1554, the Ottomans invited the Safavids to battle, then repeated the famous fatwa of Ibn Kemal.[2] The campaign, which was the third expedition during the war,[3] and was led by Suleiman himself and Governor-General of Rumelia Sokollu Mehmed Pasha, and included forces from the Balkans (the Rumelia Eyalet).[1] The Balkan forces were stationed at Tokat and spent the winter of 1553–54 there, then in June 1554 joined up with the Sultan's Army coming from Aleppo in Suşehri.[1] The Balkan forces took part in the whole campaign.[1]

The campaign

The Ottomans raided Safavid Azerbaijan and killed both Sunni and Shia.[3] Safavid palaces, villas and gardens were destroyed, and Yerevan, Karabakh and Nakhchivan were captured by the Ottomans.[4] The Mahmudi tribe in Van (not subdued by the Ottomans during the Ottoman capture of Van in 1548) under their leader Hasan, until then loyal to the Safavids, switched sides to the Ottomans following the attack on Azerbaijan in 1554.[5] Ebussuud, the Ottoman chief jurisconsult (şeyhülislâm), issued a fatwa in 1554 that endorsed the enslavement of Safavid captives, and contrary to previous practice, they could be sold like non-Muslims.[6] The Safavids did not enslave Ottoman subjects, but executed them.[6] Suleiman's army took thousands of captives in Nakhchivan in July 1554.[6] Ebussuud's fatwa did however assert that the enslavement of captured Kizilbaş (Shia) children in Nakhchivan was not lawful.[6] Suleiman threatened to destroy Ardabil and its shrine if Safavid intrusions did not stop.[4] Both sides had terrible losses, with no outright victor.[4]

Aftermath

Suleiman received a Safavid delegation at his winter quarters in Amasya to negotiate peace.[4]

Regarding territory, a Safavid recognition of Ottoman rule in Iraq and eastern Anatolia would return Yerevan, Karabakh and Nakhchivan.[4] Regarding religious matters, the Safavids were promised that Shia pilgrims would not be prevented on visiting their sanctuaries in Ottoman territory, on the condition of Safavid abolition of tabarru.[4]

The Peace was signed at Amasya and brought half a century of Ottoman-Safavid war to an end.[4] With the conclusion of hostilities in May 1555, the commanders Malkoçoğlu Balı Bey and their forces were permitted to return to Rumelia.[1] Ottoman–Safavid correspondence following the war was friendly.[4]

References

- Yürekli 2016, p. 119.

- Şahin 2013, p. 211.

- Scherberger 2014, p. 59.

- Scherberger 2014, p. 60.

- University of Wisconsin 2003, pp. 123, 134.

- Erdem 1996, p. 21.

Sources

- Books

- Erdem, Y. (1996). Slavery in the Ottoman Empire and its Demise 1800-1909. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 21–. ISBN 978-0-230-37297-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Scherberger, Max (2014). "The Sunna and Shi'a in History: Division and Ecumenism in the Muslim Middle East". In Bengio, Ofra; Litvak, Meir (eds.). The Confrontation between Sunni and Shi´i Empires. Springer. pp. 59–. ISBN 978-1-137-49506-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Şahin, Kaya (29 March 2013). Empire and Power in the Reign of Süleyman: Narrating the Sixteenth-Century Ottoman World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 211–. ISBN 978-1-107-03442-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Setton, Kenneth Meyer (1984). The Papacy and the Levant, 1204-1571. American Philosophical Society. pp. 590–. ISBN 978-0-87169-162-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Yürekli, Zeynep (2016) [2012]. Architecture and Hagiography in the Ottoman Empire: The Politics of Bektashi Shrines in the Classical Age. Routledge. pp. 119–. ISBN 978-1-317-17941-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Journals

- University of Wisconsin (2003). International Journal of Turkish Studies. 9. University of Wisconsin.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)