Sabal mexicana

Sabal mexicana is a species of palm tree that is native to far southern North America. Common names include Rio Grande palmetto,[3] Mexican palmetto, Texas palmetto, Texas sabal palm, palmmetto cabbage and palma de mícharos.[2] The specific epithet, "mexicana", is Latin for "of Mexico."[4]

| Mexican palmetto | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Clade: | Commelinids |

| Order: | Arecales |

| Family: | Arecaceae |

| Genus: | Sabal |

| Species: | S. mexicana |

| Binomial name | |

| Sabal mexicana | |

| |

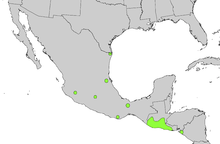

| Natural range | |

| Synonyms[1][2] | |

Description

Mexican palmetto reaches a height of 12–18 m (39–59 ft), with a spread of 3–4 m (9.8–13.1 ft). The trunk reaches 12–15 m (39–49 ft) in length and 30 cm (12 in) in diameter. The fan-shaped fronds are 1.5–1.8 m (4.9–5.9 ft) wide and attach to 90–120 cm (35–47 in) spineless petioles. Spikes 1.2–1.8 m (3.9–5.9 ft) in length yield small bisexual flowers.[5] The drupes[6] are black when ripe and 12 mm (0.47 in) in diameter.[5]

Range

The current range of S. mexicana extends from South Texas on the Gulf Coast of the United States and Nayarit on the Pacific Coast, south along both seashores to Nicaragua.[2] It is one of the most widespread and common palm trees in Mexico, where it is found in the drier lowlands.[7] Some believe that the species may have ranged much further north along the Texas Gulf Coast and as far inland as San Antonio at one time. This is supported by observations recorded in the 17th to 19th centuries, the presence of a small, disjunct population 200 mi (320 km) north of the Lower Rio Grande Valley, and the ease with which cultivated trees have become naturalized in parts of Central Texas.[8] S. mexicana should not be confused with the related and somewhat shorter "Brazoria Palm", a small population of which occurs in southeast Texas, and which is a natural hybrid of S. palmetto and S. minor.[9]

Naturally occurring S. mexicana in Texas may be difficult to discern, because this palm is widely planted as an ornamental, and because feral specimens easily become established. However, at least two populations in Texas have been reported to be purely natural. The most prominent is found in the 557-acre Sabal Palm Sanctuary located outside of Brownsville, Texas, along the banks of the Rio Grande. The second is on a much smaller tract located along the banks of Garcitas Creek, near Vanderbilt, Texas.

Uses

Mexican palmetto is grown as an ornamental for its robust, stately form, drought tolerance, and hardiness to USDA Zone 8.[10] The wood is resistant to decomposition[10] and shipworms, making it desirable for use in wharf pilings[8] and fence posts.[10] The leaves are used for thatching and making straw hats. The drupes and palm hearts are eaten.[7]

Mature S. mexicana in natural state.

Mature S. mexicana in natural state. Juvenile S. mexicana, partially maintained.

Juvenile S. mexicana, partially maintained. S. mexicana, unmaintained “boots”.

S. mexicana, unmaintained “boots”.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sabal mexicana. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Sabal mexicana |

- The Plant List

- "Sabal mexicana". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved 2010-03-23.

- "Sabal mexicana". Natural Resources Conservation Service PLANTS Database. USDA. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- Riffle, Robert Lee; Paul Craft (2003). An Encyclopedia of Cultivated Palms. Timber Press. pp. 446–447. ISBN 978-0-88192-558-6.

- Riffle, Robert Lee (2008). Timber Press Pocket Guide to Palms. Timber Press. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-88192-776-4.

- Miller, George Oxford (2006). Landscaping with Native Plants of Texas. Voyageur Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-7603-2539-1.

- Henderson, Andrew; Gloria Galeano; Rodrigo Bernal (1997). Field Guide to the Palms of the Americas. Princeton University Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-691-01600-9.

- Lockett, Landon (2006). "Sabal Mexicana Palm Trees, Native to San Antonio. And Beyond?" (PDF). Convergence and Diversity: Native Plants of South Central Texas Symposium Proceedings. Native Plant Society of Texas: 79–84.

- Goldman, Douglas; Klooster, Griffith; Fay, Chase (2011-08-25). "A preliminary evaluation of the ancestry of a putative Sabal hybrid (Arecaceae: Coryphoideae), and the description of a new nothospecies, Sabal × brazoriensis" (PDF). Phytotaxa. 1179. 27 (3163).

- "#813 Sabal mexicana". Floridata. Retrieved 2010-01-08.

External links

- "Sabal mexicana" (PDF). Digital Representations of Tree Species Range Maps from "Atlas of United States Trees" by Elbert L. Little, Jr. (and other publications). United States Geological Survey.

- Biota of North America Program 2014 county distribution map

- Interactive Distribution Map for Sabal mexicana

- Sabal Palm Audubon Sanctuary

- Native Texas Palms North of the Lower Rio Grande Valley: Recent Discoveries