SS Tubantia

SS Tubantia was an ocean liner for Royal Holland Lloyd (Dutch: Koninklijke Hollandsche Lloyd) built in 1913 by Alexander Stephen and Sons of Glasgow. She was built as a fast mail and passenger steamer for service between the Netherlands and South America. Tubantia was a sister ship of Gelria, also of Royal Holland Lloyd.

SS Tubantia | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | SS Tubantia |

| Owner: | |

| Port of registry: |

|

| Route: | Europe – South America |

| Builder: | Alexander Stephen and Sons, Glasgow[1] |

| Cost: | £300,000 |

| Yard number: | 455[1] |

| Launched: | 15 November 1913[1] |

| Completed: | March 1914[1] |

| Fate: | sunk by SM UB-13, 16 March 1916 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | ocean liner |

| Tonnage: | 13,911 GRT[1] |

| Length: | |

| Beam: | 65 ft 11 in (20.1 m)[1] |

| Propulsion: | 2 × quadruple-expansion steam engines[1] |

| Speed: | 17.5 knots (32.4 km/h)[1] |

| Capacity: |

|

| Crew: | 294[3] |

Tubantia was torpedoed and sunk by German submarine UB-13 on 16 March 1916. As a vessel of the neutral Netherlands, her sinking caused great fury amongst the Dutch public. The Germans initially claimed that Tubantia must have been sunk by a mine or a British torpedo, but when fragments of a German torpedo were found in one of Tubantia's lifeboats, the Germans claimed that UB-13 had fired the torpedo on 6 March at a British warship but it had remained active until hitting Tubantia ten days later. To redirect Dutch anger over Tubantia's sinking, Germany spread rumors of an impending British invasion of the Netherlands, which one author called a "propaganda coup".[4]

Germany initially offered a settlement of £300,000—the ship's original cost—to Royal Holland Lloyd, but was rejected. In 1922, an international arbitration committee awarded the company £830,000 compensation from Germany for the loss of the ship.

This was followed by an attempt to recover a fortune in gold coins from the wreck, which was the subject of a landmark court case, but the salvage operation was unsuccessful.

Design and construction

Tubantia was ordered by Royal Holland Lloyd from the Scottish shipbuilding firm Alexander Stephen and Sons of Glasgow. The 13,911 GRT ship was about 560 feet (170 m) long (overall) and 66 feet (20 m) abeam. She was powered by twin quadruple-expansion steam engines powered by three double-ended and six single-ended boilers. Her top speed of 17.5 knots (32.4 km/h) exceeded the design requirements.[2]

Built at a cost of about £300,000, Tubantia was, according to author Nigel Pickford, one of the most luxurious passenger ships of the era.[5] Royal Holland Lloyd made extensive use of electricity throughout Tubantia, powering everything from fans and ventilation, to laundry equipment, to cigar lighters for passengers. The ship also boasted her name spelled out in lights, suspended between the two funnels.[5] Tubantia could accommodate up to 1,520 passengers: 250 first-class, 230 intermediate-class, 140 special third-class, and 900 third-class passengers.[2] The liner was launched on 13 November 1913,[1] and completed trials in the River Clyde in March 1914.[2]

Career

Upon completion and acceptance by Royal Holland Lloyd, Tubantia was used in service between Amsterdam and Buenos Aires. At the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, Tubantia was returning from South America with £500,000 in gold destined for banks in London, a large portion of which was intended for the German Bank of London.[6] She was also carrying about 150 German reservists in steerage and a cargo of grain destined for Germany.[6][7] After making an intermediate stop in Vigo, Spain, Tubantia was stopped and boarded by an officer and crewmen from the Royal Navy cruiser Highflyer,[7] and escorted into port at Plymouth.[6] There, the German reservists were taken off Tubantia by Royal Marines;[7] the gold was confiscated and removed from the ship.[8] Although news accounts do not report when it occurred, Tubantia was released from Plymouth and allowed to resume her Royal Holland Lloyd service.

On 18 October, The New York Times carried a report that indicated Tubantia had run aground on the coast of Kent the previous day. According to the report, Tubantia was returning from Buenos Aires and suffered the accident while heading for Rotterdam with a large number of passengers. Although the article also reported that aid had been summoned from Dover, there was no indication of the extent of damage, if any, to Tubantia.[9]

In December 1915, Tubantia again made news when the Overseas News Agency in Berlin released a report saying that the British had seized all South America mail and parcels from the ship.[10] After the United States expressed concerns about related seizures from two other Dutch ships in service to the United States—Nieuw Amsterdam and Rijndam—the British Foreign Office issued a statement that reported that contraband intended for Germany—which included four packages of rubber, and seven containers of wool—had been found among Tubantia's mail.[11]

Sinking

Tubantia began her regularly scheduled voyage from Amsterdam to Buenos Aires on 15 March 1916 nearly empty of passengers,[5] despite Royal Holland Lloyd advertisements that boasted of "submarine signalling apparatus" on their passenger ships.[12] After sailing to a position about 4 nautical miles (7.4 km) from the North Hinder Lightship, about 50 nautical miles (93 km) off the Dutch coast, Tubantia anchored at about 02:00 on 16 March to wait for daylight and avoid any chance of misidentification or attack. To that end, the ship was completely illuminated.[13]

At about 02:30, crewmen aboard Tubantia spotted a stream of bubbles rapidly approaching the ship's starboard side, followed by an explosion. The ship quickly began sinking.[13] Distress calls sent out by Tubantia were answered by three ships, Breda, Krakstau, and La Campine, which between them rescued all 80 passengers and all 294 members of the crew.[3] The ship and her cargo were a total loss.[13] Tubantia was the largest neutral vessel sunk during the entire war.[13]

Aftermath

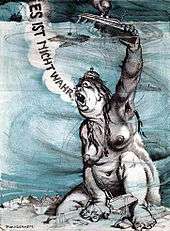

A war in the British and German press erupted, with vigorous attempts to blame the British by the Germans, and angry rebuttals by the British. Both sides had in mind the egregious violation of Dutch neutrality. The German press first proffered the explanation that Tubantia must have been sunk by a British mine. The British reported that the liner had been sunk by a German torpedo; the German press countered by saying that if it were a torpedo that sank the ship, it had to have been a British one. The matter was seemingly settled when a stray lifeboat of Tubantia's was examined and torpedo fragments made of bronze were found embedded in it; Germany was the only country that used bronze in its torpedoes.[3]

Presented with evidence that it was torpedo no. 2033 which had been assigned to the small, coastal submarine UB-13,[Note 1] the Germans presented a forged log from UB-13 that showed her nowhere near Tubantia at the time of the attack. Further, they reported, UB-13 had fired that specific torpedo at a British warship on 6 March, ten days before Tubantia was sunk.[14] The U.S. Minister to the Netherlands, Henry van Dyke, writing in Fighting for Peace in 1917, called this explanation "amazing" and derided it:

This certain U-boat had fired this particular torpedo at a British war-vessel somewhere in the North Sea ten days before the Tubantia was sunk. The shot missed its mark. But the naughty undisciplined little torpedo went cruising around in the sea on its own hook for ten days waiting for a chance to kill somebody. Then the Tubantia came along and the wandering-Willy torpedo promptly, obstinately, ran into the ship and sank her. This was the explanation. Germany was not to blame.[15]

The Dutch public was furious at what they believed a hostile German act. To help divert the public anger against his country, German diplomat Richard von Kühlmann began a coordinated campaign to spread rumors of an impending British invasion of the Netherlands. Author Hubert van Tuyll van Serooskerken called the German plan a "propaganda coup", and reports in his book The Netherlands and World War I that the rumors caused some panic in the streets and forced the government to declare a four-day emergency from 30 March to 2 April.[4]

Despite denials and rumor-spreading, Germany nevertheless offered compensation in the amount of £300,000, Tubantia's original cost. Rejected by the Dutch, the two countries agreed to have the issue arbitrated after the end of the war. The dispute was finally settled in 1922, when compensation in the amount of £830,000 was awarded to Royal Holland Lloyd.[3]

Salvage attempt

In 1924 the wreck was the subject of a salvage dispute between two sets of salvors, both seeking to recover a reputed £2 million worth of gold coins from it (£100 million in 2012 prices). This was resolved in the English court decision The Tubantia [1924] P 78, and remains the leading authority under English law as to when a salvor takes possession of a sunken shipwreck. The winning party, war hero Sydney Vincent Sippe, spent three years and £100,000 trying to access the gold, but abandoned the attempt after concluding that it was too dangerous for divers to recover it.[16]

Notes

- Sources almost invariably report the submarine as U-boat 13 or U-13. UB-13 was the only extant U-boat numbered 13 in March 1916; U-13 and UC-13 had been lost in 1914 and 1915, respectively.See: Helgason, Guðmundur. "WWI U-boats: U 13". German and Austrian U-boats of World War I - Kaiserliche Marine - Uboat.net. Retrieved 16 March 2009. Helgason, Guðmundur. "WWI U-boats: UB 13". German and Austrian U-boats of World War I - Kaiserliche Marine - Uboat.net. Retrieved 16 March 2009. Helgason, Guðmundur. "WWI U-boats: UC 13". German and Austrian U-boats of World War I - Kaiserliche Marine - Uboat.net. Retrieved 16 March 2009.

References

- "Tubantia (5603846)". Miramar Ship Index. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- "New Dutch liner for South American service is ready". The Christian Science Monitor. 2 April 1914. p. 2.

- Pickford, p. 214.

- van Tuyll van Serooskerken, p. 160.

- Pickford, p. 213.

- "British capture $2,500,000 prize". The Washington Post. 8 August 1914. p. 1.

- "3,600 refugees home on 2 ships". The New York Times. 18 August 1914. p. 5.

- "South American gold arrives in England". The Wall Street Journal. 8 August 1914. p. 4.

- "Dutch steamer ashore". The New York Times. 18 October 1914. p. 4.

- "British seize more mail". The New York Times. 29 December 1915. p. 3.

- "British send note on mail detention". The New York Times. 27 January 1916. p. 2.

- Wood, front endpaper.

- Van Tuyll van Serooskerken, p. 159.

- Wilson, George Grafton (1922). "Report of the International Commission of Inquiry in the Loss of the Dutch Steamer Tubantia". The American Journal of International Law. 16: 432. doi:10.2307/2188183. ISSN 0002-9300. OCLC 1480149.

- van Dyke, p. 430.

- Pickford, Nigel (2006). Lost Treasure Ships of the Northern Seas: A Guide and Gazetteer to 2000 Years of Shipwreck. London: Chatham. ISBN 978-1-86176-250-4. OCLC 67375472.

Bibliography

- van Dyke, Henry (1921). The Works of Henry Van Dyke (Avalon ed.). New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 0-665-81693-6. OCLC 9473678.

- van Tuyll van Serooskerken, Hubert P. (2001). The Netherlands and World War I: Espionage, Diplomacy and Survival. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-12243-7. OCLC 48081143.

- Wood, Ruth Kedzie (1913). The Tourist's Spain and Portugal. New York: Dodd, Mead and Co. OCLC 370539.