SS Pacific (1849)

SS Pacific was a wooden-hulled, sidewheel steamer built in 1849 for transatlantic service with the American Collins Line. Designed to outclass their chief rivals from the British-owned Cunard Line, Pacific and her three sister ships (Atlantic, Arctic and Baltic) were the largest, fastest and most well-appointed transatlantic steamers of their day.

.jpg) | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Pacific |

| Namesake: | Pacific Ocean |

| Operator: | Collins Line |

| Route: | New York-Liverpool |

| Builder: | Brown & Bell, New York |

| Cost: | $700,000 |

| Launched: | 1 Feb 1849 |

| Maiden voyage: | 25 May 1850 |

| Honors and awards: | Blue Riband holder, 21 Sep 1850–16 Aug 1851 |

| Fate: | Lost with all aboard under unknown circumstances, January 1856 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Passenger |

| Tonnage: | 2,707 gross tons |

| Length: | 281 ft (85.6 m) |

| Beam: | 45 ft (13.7 m) |

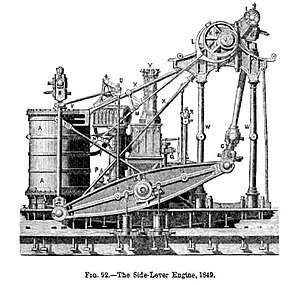

| Propulsion: | 2 × 95-inch cylinder (2.4 m), 9-foot stroke (2.7 m) side-lever engines, auxiliary sails |

| Speed: | 12.5 knots (23.2 km/h; 14.4 mph) |

| Capacity: | Passengers: 200 1st class, 80 2nd class |

| Crew: | 141 |

Pacific's career began on a high note when she set a new transatlantic speed record in her first year of service, but after only five years in operation, the ship along with her entire complement of almost 200 passengers and crew vanished, without a trace, on a voyage from Liverpool to New York City, which began 23 January 1856. Pacific's fate remains a mystery to the present day. A message in a bottle found on the remote island of Uist within the Hebrides (a widespread archipelago off the west coast of mainland Scotland) in 1861 declared her sunk by icebergs. In 1991, wreckage located in the Irish Sea off the coast of Wales was claimed, without corroboration, as being the SS Pacific.

Development

For several decades prior to the 1840s, American sailing ships had dominated the transatlantic routes between Europe and the United States. With the coming of oceangoing steamships however, the U.S. lost its dominance as British steamship companies, particularly the government-subsidized Cunard Line, established regular and reliable steam packet services between the U.S. and Britain.[1]

In 1847, the U.S. Congress granted a large subsidy to the New York and Liverpool United States Mail Steamship Company (S.S.C.) for the establishment of an American steam-packet service to compete with Britain's Cunard Line.[2] With this generous subsidy in hand, the New York and Liverpool S.S.C. ordered four new ships from New York shipyards and established a new shipping line, the Collins Line, to manage them. The Collins Line ships were specifically designed to be larger and faster, and offer a greater degree of passenger comfort, than their Cunard Line counterparts.[1] Design of the ships was entrusted to a noted New York marine architect, George Steers.[3]

Description

Pacific's 281-foot (85.6 m) wooden hull was built from yellow pine, with keel and frames of white oak and chestnut. Like her three sister ships, Pacific had straight stems, a single smokestack, three square-rigged masts for auxiliary power, and a flat main deck with two single-story cabins, one fore and one aft.[2] The ships were painted in Collins Line colors: black hull with a dark-red stripe running the length of the ship,[4] and a black stack with a dark-red top.

Pacific was powered by two side-lever engines built by the Allaire Iron Works of New York, each of which had a 95-inch cylinder (2.4 m) and 9-foot stroke (2.7 m), delivering a speed of 12 to 13 knots (22 to 24 km/h; 14 to 15 mph). The running gear was designed in such a way that if one engine failed, the remaining engine could continue to supply power to both paddlewheels. Steam was supplied by four vertical tubular boilers, with a double row of furnaces, designed by the Line's chief engineer, John Faron.[5] Fuel consumption was from about 75 to 85 short tons (68 to 77 t) of coal per day, and auxiliary sail power was provided by three full-rigged masts.

The passenger accommodations were generous and spacious, and the cabins and saloons were elaborately decorated.[5] The ship could initially accommodate 200 first-class passengers; in 1851, accommodations for an additional 80 second-class passengers were added.[6] Customer service innovations on the Collins Line ships included steam heating in the passenger berths, a barber's shop, and a French maitre de cuisine.[4] The ships' high freeboards and straight stems also contributed to passenger comfort by providing added protection from seaspray and a steadier motion through the waves than typical passenger ships of the period.[7]

Service history

Pacific was launched on 1 February 1849 and made her maiden voyage from New York to Liverpool on 25 May 1850. She would retain service on the New York-Liverpool route for her entire career.[6]

Between 11 and 21 September, Pacific made a record passage from Liverpool to New York with an average speed of 12.46 knots (23.08 km/h; 14.34 mph), breaking the previous record of 12.25 knots held by the Cunard Line's Asia, and thus winning the coveted Blue Riband for fastest transatlantic crossing. Pacific would hold the record for less than a year however, as her sister ship Baltic would set a new record the following August with a new record speed of 12.91 knots (23.91 km/h; 14.86 mph). Between 10 and 20 May 1851, Pacific also set a new eastbound record with an average speed of 13.03 knots, beating the previous record of 12.38 knots set by the Cunard Line's Canada. Again however, the record would stand for only nine months before being broken again by Pacific's slightly more-powerful sister ship, Arctic.[6]

In 1851, Pacific's passenger accommodations were increased to include an additional 80 second-class passengers.[6] In March 1853, Pacific rescued the crew of the barque Jesse Stevens, which had foundered in the Atlantic Ocean.[8][9]. In 1853, Pacific's mizzen mast was removed,[6] presumably in order to reduce drag.

Loss

On 23 January 1856, Pacific departed Liverpool for her usual destination of New York, carrying 45 passengers (a typically small number for a winter voyage) and 141 crew. Her commander was Captain Asa Eldridge, a Yarmouth, Cape Cod skipper and navigator of worldwide reputation; in 1854 he had set a trans-Atlantic speed record on the clipper Red Jacket from New York to Liverpool which remains unbroken. After Pacific failed to arrive at New York, other ships were sent to conduct a search, but no trace of the vessel was found. Contemporaries concluded that Pacific had probably hit an iceberg off Newfoundland, as the ice had been particularly bad that year.[10] Captain Eldridge and his chief engineer, Samuel Matthews, were both still new to the Pacific, making only their second roundtrip voyage on her, and some accounts have blamed the disaster on their inexperience. But as a more recent account explains, both had considerable relevant experience: the Pacific was actually the fourth steamer Eldridge had commanded, while Matthews had a long career on other steamships, including another Collins liner whose engines and boilers were identical to the Pacific's.[11]

Wyn Craig Wade mentions the missing ship in his 1979 book, The Titanic: End of a Dream. Wade wrote, "The only clue in this instance had been a note in a bottle, washed ashore on the west coast of the Hebrides" as follows:

- On board the Pacific from Liverpool to N.Y. - Ship going down. Confusion on board - icebergs around us on every side. I know I cannot escape. I write the cause of our loss that friends may not live in suspense. The finder will please get it published. W.M. GRAHAM.

Author Jim Coogan also mentions the missing vessel in his article "A Message from the Sea" published in The Barnstable Patriot. Coogan writes that after the bottle was found, "on the remote Hebrides island of Uist... in the summer of 1861", the passenger list was thoroughly checked by the London Shipping & Mercantile Gazette, "and when the passenger list of the ill-fated steamer was examined, it contained the name of William Graham, a British sea captain headed for New York as a passenger to take command there of another vessel."[12]

Coogan's article goes on to say:

- "...in 1991, divers found the bow section of the SS Pacific in the Irish Sea only 60 miles [97 km] from Liverpool. Other than the claim, there is no other confirmation of the find, nor is it found in any other book... that no wreckage from the lost ship came ashore along the coast of Wales in the aftermath of her disappearance would...make it unlikely the ship foundered so close to Liverpool."[13]

Supporting this view, a recent book argues that the evidence used to identify the Welsh wreck as the remains of the Pacific is far from conclusive, and that in the absence of further information about that wreck, the note in the bottle that washed ashore in the Hebrides still represents the best explanation of the steamer’s disappearance.[14][15] This conclusion is further reinforced by the evidence from more recent dives which found brass plates, cast-iron irons and copper discs dated 1865, 1863 and 1865 respectively. As a result the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales has concluded that the wreck is unlikely to be that of the Pacific.[16]

Among those lost was Bernard O'Reilly, Bishop of Hartford (Connecticut), who was returning to his diocese after an 1855 trip to Europe.

Footnotes

- Fry, p. 66.

- Morrison, pp. 411–412.

- Morrison, p. 411.

- Morrison, p. 420.

- Morrison, p. 412.

- North Atlantic Seaway by N.R.P. Bonsor, vol.1, p.207, as recorded at Ship Descriptions P-Q Archived 2009-12-15 at the Wayback Machine, The Ships List website.

- Fox, pp. 120, 124-125.

- "A Thrilling Incident at Sea - Sixteen Lives Saved". Freeman's Journal and Daily Commercial Advertiser. Dublin. 23 March 1853.

- "America". The Liverpool Mercury etc (2500). Liverpool. 10 May 1853.

- Fox, pp. 135-136.

- Miles, p. 120.

- Barnstable Patriot.com Archived 2014-10-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Barnstablepatriot.com Archived 2014-10-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Miles

- Sloan

- http://www.coflein.gov.uk/en/site/240648/details/unnamed-wreck

References

- Bonsor, N. P. R.: North Atlantic Seaway, Volume I, unknown edition, page 407.

- Coogan, Jim: "A Message from the Sea", The Barnstable Patriot

- Fox, Stephen (2003): Transatlantic: Samuel Cunard, Isambard Brunel, and the Great Atlantic Steamships, HarperCollins, page 135, ISBN 978-0-06-019595-3.

- Fry, Henry (1896): The History of North Atlantic Steam Navigation: With Some Account of Early Ships and Shipowners, Sampson Low, Marston and Company, London.

- Miles, Vincent (2015): The Lost Hero of Cape Cod: Captain Asa Eldridge and the Maritime Trade That Shaped America, Historical Society of Old Yarmouth, Yarmouth Port, Massachusetts.

- Morrison, John Harrison (1903): History Of American Steam Navigation, W. F. Sametz & Co., New York. Reprinted in 2008 by READ BOOKS, ISBN 978-1-4086-8144-2.

- Sloan, Edward W (1993) The Wreck of the Collins Liner Pacific - A Challenge for Maritime Historians and Nautical Archaeologists. Bermuda Journal of Archaeology and Maritime History, Volume 5, pp. 84-91.

- Wade, Wyn Craig. The Titanic: End of a Dream. 1979, p. 57.

External links

| Records | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Asia |

Holder of the Blue Riband (Westbound record) 1850 - 1851 |

Succeeded by Baltic |

| Preceded by Canada |

Blue Riband (Eastbound record) 1851 - 1852 |

Succeeded by Arctic |