SS Otsego

SS Otsego was an American merchant ship that saw service after World War I as a US Navy troop transport and again during World War II as a US Army troop transport. Prior to her American service, she was a German cruise ship, and she went to the Soviet Union under Lend-Lease in the twilight of her career.

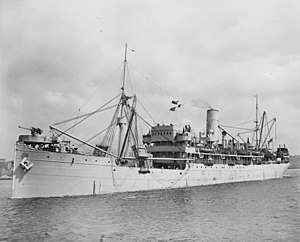

USAT Otsego, August 1943 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | SS Otsego |

| Owner: |

|

| Operator: |

|

| Builder: | Reiherstieg Schiffswerfte & Maschinenfabrik (Hamburg, Germany) |

| Yard number: | 408 |

| Launched: | 21 Dec 1901 |

| Christened: | Prinz Eitel Friedrich |

| Completed: | 19 April 1902 |

| Commissioned: | USN: 10 Mar 1919–28 Aug 1919 |

| In service: | 1902–14; 1917–19; 1921; 1924–55 |

| Out of service: | 1914–17; 1919–20; 1921–23 |

| Renamed: |

|

| Refit: |

|

| Fate: | Hulked near Vladivostok, March 1955 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Passenger-cargo (German merchant, 1902–14) |

| Tonnage: | |

| Length: | 370 ft (110 m) |

| Beam: | 45 ft 3 in (13.79 m) |

| Draft: | 25 ft 4 in (7.72 m) |

| Depth of hold: | 26 ft 8 in (8.13 m) |

| Decks: | 2 continuous |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: | Single screw propeller |

| Speed: | 12 knots (14 mph; 22 km/h) |

| Capacity: |

|

| Crew: | 46 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Troop transport (U.S. Navy, 1919) |

| Displacement: | 8,755 long tons (8,895 t) |

| Troops: | 28 officers, 984 enlisted |

| Complement: | 21 officers, 168 enlisted |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Passenger-cargo (U.S. merchant, 1924–41) |

| Capacity: |

|

| Crew: | 63 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Troop transport (U.S. Army, 1941–44) |

| Speed: | 10.5 knots (12 mph; 19 km/h) |

| Troops: | 793 |

Otsego was originally SS Prinz Eitel Friedrich, a passenger-cargo steamer built in Germany in 1901–02 for the Hamburg America Line. The steamer initially served on trade routes between Germany and South America before becoming a cruise ship in 1906, thereafter making tours from New York City to the tropics. Prinz Eitel Friedrich was one of the first ships on the scene in 1907 after the devastating earthquake at Kingston, Jamaica, where she embarked American refugees.

The ship was interned in New York at the outbreak of World War I, then seized by US authorities following the entry of the United States into the war in April 1917. She was renamed Otsego and used to transport troops, weapons, and supplies to France. After the war, Otsego was converted into a troop transport and commissioned into the US Navy as USS Otsego (ID-1628). Between March and August 1919, USS Otsego repatriated about 3,500 US troops from France to the United States. She reverted to the name SS Otsego following her decommissioning and was refitted as a cargo ship, but she was then laid up for some years after failed attempts to sell or charter the vessel.

In 1924, Otsego was purchased by Libby, McNeill & Libby, a canned food manufacturer. She was refitted to carry both passengers and cargo and used to transport employees, supplies, and product between Seattle, Washington and the company's Alaskan salmon canneries. After 18 years of service with Libby's, the ship was chartered to the US Army in 1941, shortly before the United States' entry into World War II. She was converted into the troop transport USAT Otsego and used to convey troops and supplies between Seattle and various Alaskan military bases.

In January 1945, Otsego was handed to the Soviet Union under Lend-Lease and renamed SS Ural. The ship operated in Siberian waters and may have been used to transport prisoners to various Siberian prison and labor camps. In 1947, she was renamed SS Dolinsk. Dolinsk was hulked or scrapped in the vicinity of Vladivostok in 1955.

Design and construction

Prinz Eitel Friedrich was a steel-hulled, screw-propelled passenger-cargo ship built in Hamburg, Germany in 1901–02 by Reiherstieg Schiffswerfte & Maschinenfabrik for the Hamburg America Line,[1][2] named after Prince Eitel Friedrich of Prussia, son of German Emperor Wilhelm II. The ship was launched on 21 December 1901 and delivered on 19 April 1902, yard number 408.[2]

Prinz Eitel Friedrich had a length of 370 feet (112.8 m), beam of 45 feet 3 inches (13.8 m), hold depth of 26 feet 8 inches (8.1 m), and draft of 25 feet 4 inches (7.7 m). She had a gross register tonnage of 4,650, net register tonnage of 2,920,[3][4][5] and a displacement of 8,755 long tons (8,895 t) (as calculated during later naval service).[1][lower-alpha 1] The vessel had two continuous decks, two masts and one smokestack, moderately raked,[6] and nine waterproof bulkheads; she was also fitted with water ballast tanks.[4]

The ship was powered by a 2,400 indicated horsepower (1,790 kW), four-cylinder, vertical quadruple expansion steam engine with cylinders of 22.5, 32.25, 47 and 68 inches (57, 82, 119 and 173 cm) by 47.25-inch (120 cm) stroke, driving a single screw propeller.[3][4][5] Steam was supplied by two 20 ft 6 in (6.2 m) by 12 ft 3 in (3.7 m) double-ended, coal-fired Scotch boilers[3][4][5] with a working pressure of 220 psi (1,517 kPa).[4] The coal bunkers had a total capacity of about 1,400 tons, giving a range of 11,000 nautical miles (12,659 mi; 20,372 km),[3] and the ship had a service speed of 12 knots (14 mph; 22 km/h).[1]

Prinz Eitel Friedrich had accommodation for 100 first-class passengers quartered amidships, 634 steerage passengers housed aft on the main deck, and a crew of 46 housed forward. Passenger facilities included a dining saloon and small social hall, both on the promenade deck, and a smoking room aft of the engineroom casing. There were four cargo hatches, two forward and two aft. The ship carried eight lifeboats on radial davits. A distinctive feature of the vessel was a "lavish use of mahogany on the wheelhouse and bridge fronts".[6]

Service history

German merchant service, 1902–1914

After delivery in April 1902 to her owner, the Hamburg America Line, Prinz Eitel Friedrich began her career by making one or two voyages from Wilhelmshaven, Germany, to St. Thomas, Virgin Islands, transporting general cargoes outbound and fresh fruit inbound. In June, the vessel was reassigned to service between Hamburg and Brazil, on which route she would continue to operate for the next four years.[7]

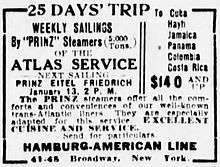

In 1906, the ship was transferred to the Atlas Line, a subsidiary of the Hamburg America Line, to join a new, five-ship winter tour service operating from New York to the tropics.[7][8] Prinz Eitel Friedrich consequently departed Germany for New York, arriving 26 April; she carried 572 third-class passengers on this trip.[7]

The five[8]—later eight[9]—ships assigned to the Atlas Line's tropical tours, including Prinz Eitel Friedrich, eventually offered round trips from New York of either 11, 18, or 25 days,[10] with one ship scheduled to be departing New York every week.[9][11] Prinz Eitel Friedrich appears to have operated almost exclusively on the longer (25-day) cruises, usually in tandem with her stablemate Prinz Sigismund.[9][12] Prospective customers were assured of "accommodations equal to those of the well-known Trans-Atlantic liners of the Hamburg-American Line",[8] along with "excellent cuisine and service".[13]

While the exact itinerary might vary from year to year, localities typically visited on the tours included Jamaica, Haiti, Cuba, Colombia, Costa Rica and Panama.[10][13][14] At the latter, the ships offered a connecting service to Peru and Chile.[14] The call at Panama would also usually entail a two- or three-day stopover, with "optional shore excursions", while the ships exchanged cargoes and through-passengers.[15] At this time, the Panama Canal was still under construction, and Prinz Eitel Friedrich and other ships of the Line frequently arrived with supplies for the construction work.[lower-alpha 2]

Prinz Eitel Friedrich's first season on the winter tour service proved to be an eventful one. After departing Colon, Panama on 12 January 1907, the vessel was due to make port at Kingston, Jamaica on 14 January when a devastating earthquake struck the island, killing as many as 1,745 people and causing widespread destruction.[19][20] Though initially reported to have been stranded in the harbor along with several other ships,[19] Prinz Eitel Friedrich was in fact still operational,[lower-alpha 3] and over the course of the next three days, took aboard some 160 American refugees.[24] With her first-class accommodations "taxed to their capacity",[24] the vessel then departed for New York, where on 23 January, she became the first ship to return there from the disaster.[24] On arrival, the passengers passed a resolution condemning the "inactivity and utter inefficiency" of the British authorities at Jamaica after the quake, along with the latters' alleged neglect of the Americans in favour of British refugees.[25][lower-alpha 4]

By 1911, the Atlas Line was running its tropical tours all year round,[27] though summer tours starting at around $115 for the round trip[10] were somewhat cheaper than the more popular winter tours, with an entry price of $135–150.[9][11][27] In February 1914, Michel Oreste, President of Haiti, abdicated his position in the face of advancing rebel forces, and together with his family and entourage, fled his native country aboard Prinz Eitel Friedrich, his party disembarking at Kingston, Jamaica, on the 9th.[28][29]

On 1 August 1914, with the outbreak of World War I imminent, the Atlas Line announced the suspension of its services, effective immediately. Ships of the Line already in American ports were ordered to remain there, while ships in transit to a U.S. port were instructed to complete their voyages and then cease operation.[30] When war was declared a few days later on 4 August, Prinz Eitel Friedrich was still in transit from Bahamas to New York, and the ship responded to the news by hugging the New Jersey coastline for the remainder of the voyage, attempting to stay within the three-mile limit of the still-neutral United States to avoid possible capture by Allied forces.[31] Before dawn on 5 August, Prinz Eitel Friedrich, with all but her navigation lights covered, slipped quietly into New York Harbor,[32] where she would remain in internment for the next two years and eight months.[lower-alpha 5]

Seizure and U.S. Navy service, 1917–1919

_guarded_by_police%2C_New_York%2C_February_1917.jpg)

On 3 February 1917, the United States broke diplomatic relations with Germany over Germany's resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare. Shortly after, a police guard was posted over Prinz Eitel Friedrich and other German ships interned in New York Harbor.[34] On 6 April, the United States declared war on Germany and seized more than 90 German ships, including Prinz Eitel Friedrich; they were turned over to the United States Shipping Board (USSB) for possible wartime use.[35] Shortly after, the Board renamed Prinz Eitel Friedrich the SS Otsego.[36][lower-alpha 6]

Otsego was used during the war to transport guns and other supplies to Europe, as well as some troops.[36] After the war, the foreign contingent of the American Cruiser and Transport Force withdrew, necessitating a rapid expansion of the US Navy's troop transport fleet in order to return troops to the United States. A total of 56 ships in the government's possession were selected for conversion to troop transports, including Otsego.[37] She was converted from 15 January to 3 March 1919 by the W. & A. Fletcher Company of Hoboken, New Jersey at a cost of $144,000.[38] While still undergoing conversion, the ship was transferred to the US Navy on 7 February and commissioned the same day as USS Otsego (ID-1628), with Lieutenant Commander Henry Fletcher Long, USNRF in command.[1] After conversion, the ship had a troop capacity of 28 officers and 984 enlisted men,[38] and a crew complement of 21 officers and 168 enlisted men.[39][lower-alpha 7]

USS Otsego was assigned to the Newport News Division of the Cruiser and Transport Force, and she made four round-trips to repatriate troops from France to the United States between 10 March and 28 August 1919.[1] On her first crossing, the ship carried hay and automobile parts to Le Verdon-sur-Mer and returned 1,036 officers and men of the 19th, 20th, 30th, 35th, 36th, and 45th Balloon Companies from Bordeaux to New York 18 April.[1][40] The returned servicemen on this voyage included 74 men convalescing from illness or wounds, the majority of whom had suffered a leg amputation.[41]

On her next trip from France, Otsego departed Bordeaux 11 May[42] with 24 officers and 987 enlisted men, including headquarters and medical detachments of the First Battalion and Companies A, B, and C of the 311th Regiment, 78th Division, arriving New York 26 May.[43] The ship had been expected on the 23rd but was delayed for four days with boiler trouble, apparently disrupting the plans of New Jersey Governor William Nelson Runyon, who had travelled to Brooklyn on the earlier date to welcome the ship.[44] The vessel was nonetheless accorded an enthusiastic reception on the 26th, greeted by a fleet of steamers "with bands playing and flags flying and banners indicating the different towns from which they hailed", while soldiers aboard Otsego "swarmed the decks cheering and seeking and finding their relatives in the aquatic escort".[43] The returning soldiers on this voyage included seven winners of the Distinguished Service Cross.[43]

Otsego's third repatriation voyage returned 1,020 troops to Charleston, South Carolina on 2 July, consisting mostly of supply and transport units and "749 negro enlisted men".[45][46] The ship's final voyage from France returned 392 officers and men from a variety of supply, medical, veterinary, and other units, arriving at New York on 28 August. Among those returning on this voyage was William J. Long, the American Expeditionary Force's doughnut-eating champion, credited with eating 249 doughnuts[lower-alpha 8] in a single 24-hour period during a July 4 contest; his rival went to the hospital after eating 189.[47][48]

On returning to New York on 28 August, USS Otsego was decommissioned and detached from the Cruiser and Transport Force the same day, her name reverting to SS Otsego; she was delivered to the USSB at New York 19 September 1919.[1] During her brief naval career, the ship had repatriated a total of 3,446 troops from France to the United States, including 79 sick or wounded.[49]

Failed plans and lay-up, 1919–1923

After their naval decommissioning, the government was unsure what to do with the ex-German ships in its possession. Plans were drawn up to auction nineteen of the vessels, including Otsego,[50] but the USSB also contracted on 5 November 1919 with J. W. Millard & Bro., naval architects, for the redesign of Otsego[51] as a "modern passenger ship".[lower-alpha 9] The proposed redesign was accepted by the Board on 10 February 1920,[51] but the auction went ahead regardless on 17 February.[50] The auction closed unsuccessfully, having attracted only a single bid for any of the nineteen ships—a $550,000 offer from the Acme Operating Corporation for Otsego, which was rejected.[50]

With the failure of the auction, the USSB proceeded with its alternative plan for Otsego, inviting tenders for the refit of the vessel as a passenger ship per the Millard plans. Tenders were received ranging from $970,000 to $1,477,576, but on 25 March these were also rejected by the Board.[51] On 17 May, Otsego was towed to the Portsmouth Navy Yard "to be reconditioned for cargo-carrying purposes only", with the work expected to completed by September.[51] Work carried out on the vessel during the refit included replacement of the ship's original boilers with three new Foster water-tube boilers, as well as reconditioning of the engine, propeller shaft and auxiliary engines.[lower-alpha 10]

After her refit as a cargo ship, Otsego, along with five other ex-German ships, was put up for auction again on 10 June 1921, but on this occasion none of the vessels attracted a bid.[54] The USSB then decided to return Otsego to service under charter. In late June, she was chartered to the Cosmopolitan Steamship Company,[55] a French-American company, for the purpose of testing the competition on a direct route from Boston, Massachusetts to Liverpool, England. Departing New York, Otsego arrived at Boston on 8 July, where she loaded 200,000 bushels of oats bound for Dunkirk, France, plus general cargoes bound for Liverpool,[56][57] before departing for these ports on or about 18 July.[58] By late August the ship was back in New York, where, having made only one round trip for the Cosmopolitan Line, she was withdrawn from the service due to "depressed market conditions".[59] At this point, having exhausted its options, the USSB had Otsego laid up, in which state she would remain for the next two years and five months.[60]

Libby, McNeill & Libby, 1924–1941

On 29 January 1924, Otsego was purchased by Libby, McNeill & Libby, an American canned food company that ran a number of salmon canneries in Alaska. Following the purchase, a crew made up partly of the company's idle cannery workers, commanded by Captain Neilson, was despatched to New York to man the ship. After being removed from lay-up, Otsego travelled to Seattle, Washington via Baltimore, Newport News, the Panama Canal, Los Angeles and San Francisco, arriving on 6 April 1924.[61]

As the salmon canning industry was seasonal, Otsego's main duty for her new owners was to make a single round trip per year, transporting packing supplies, cannery workers and provisions from Seattle to the company's Alaskan canneries in the Spring, and returning the employees together with the canned salmon in the Fall. The company had previously relied upon two slow motorboats and a small fleet of ageing sailing ships to maintain its salmon canneries, so Otsego's purchase represented a substantial upgrade to the company's transport capabilities.[61]

To prepare Otsego for her new role, the vessel was given another refit. New cabin berths were added, and the ship's steerage space was upgraded for the cannery workers and fishermen, after which, the ship had a total of 219 cabin berths and a further 214 berths in dormitories. Additionally, a new deck was added above the steering engine house at the stern, and the mahogany woodwork on the wheelhouse and bridge fronts was restored. The ship's radial lifeboat davits were also gradually replaced with more modern luffing davits when circumstances allowed.[61]

After a trial trip on Puget Sound, Otsego entered service for her new employers on 11 May, bound for Bristol Bay, Alaska. Throughout her service with Libby's, Otsego would be manned largely by the company's fishermen and cannery workers rather than by professional seamen, an arrangement that would later become unviable due to unionization. After arrival at Bristol Bay, the bulk of the 63-man crew would go ashore along with the other employees to work "day and night" to finish the season's canning, leaving only a skeleton crew behind to tend the ship.[61] Returning to Seattle on 20 August, Otsego demonstrated her advantages by making an additional two trips to Bristol Bay the same season, an occurrence "unheard of in the trade at the time".[61] In her second season for the company, Otsego towed the old sailing ship Oriental both ways on the latter's final voyages.[61]

Libby's satisfaction with the performance of Otsego can be gauged by the fact that in 1926, the company purchased Otsego's sister ship and former Atlas Line stablemate Prinz Sigismund, by now going under the name General W. C. Gorgas. A third ship, Santa Olivia, was added to the company fleet in 1936 and renamed David W. Branch.[61]

During her long career with Libby's, Otsego suffered few accidents, but two are worthy of note. On 7 August 1933, the vessel went aground in dense fog when heading for Shilshole Bay; she was returned to service the following day by the tugboat Creole. A more serious accident occurred about a year later on 31 July 1934 when Otsego, carrying some 600 cannery workers and a full cargo of canned salmon, struck a rock off Cape Mordvinof in Bristol Bay. Refloated, the badly leaking vessel was escorted by the United States Coast Guard cutters Ewing and Bonham to Dutch Harbor the following day, where her passengers and cargo were transferred to other ships. After temporary repairs, Otsego completed the voyage to Seattle under escort from the cutter Shoshone, where she had about 70 hull plates repaired or replaced by Todd Corporation.[61][62]

In addition to her annual round trips to Alaska, Otsego made 42 shorter trips for Libby's during her eighteen years of company service, for a total of about 60 voyages. Otsego's final voyage for Libby, McNeill & Libby ended at Lake Union on 30 August 1941. The ship was then briefly chartered to the States Steamship Company of Portland, Oregon, but before being transferred, was chartered instead to the War Shipping Administration, which in turn chartered the vessel to the U.S. Army on 4 December—three days before the Attack on Pearl Harbor that brought the United States into World War II.[61]

World War II and later service

.jpeg)

As USAT Otsego, the ship made her first voyage under US Army control when she departed Seattle on 19 December 1941. From April to July 1942, she was given an extensive recondition and refit as a troop transport at Seattle, after which she could accommodate 793 troops;[61][63] her service speed by this time was listed at 10.5 knots (12.1 mph; 19.4 km/h).[63]

USAT Otsego was home-ported at Seattle and spent the next 2½ years as an army transport in "arduous"[63] service to "most of the important ports and military bases in Alaska",[61] making 31 voyages from 1941 through 1944.[63][64] On 9 December 1944, she was delivered to the War Shipping Administration.[63][64] By this time, unionization had made Libby's private fleet uneconomic and the company had no further use for the ship, so the aging vessel was transferred to the Soviet Union in January 1945 under Lend-Lease and renamed SS Ural.[2][63][64] The ship was placed under the control of the Far Eastern Steamship Company of Vladivostok and may have been used to transport political prisoners, forced laborers, and criminals from the Eastern terminals of the Trans-Siberian Railway to camps in Kamchatka and Northeast Siberia.[65]

In 1947, Ural was reportedly renamed SS Dolinsk;[2][65] she was hulked[2] or scrapped[65] in the region of Vladivostok in 1955.[2][65] Her sister ship General W. C. Gorgas had also become a US Army troop transport in 1941 and a Soviet Lend-Lease ship in 1945; she was scrapped in the Soviet Union in March 1958.[65][66]

Footnotes

- Note that ship dimensions and tonnages typically vary slightly from source to source.

- Examples:[16][17][18]

- The wrecked vessel was not, as first reported, Prinz Eitel Friedrich, but her stablemate Prinz Waldemar, which went aground about ten miles east of Kingston, near the Plum Point lighthouse which had been destroyed by the earthquake.[21] Prinz Waldemar proved unsalvageable and was never returned to service.[22][23]

- The American refugees were particularly scathing in their criticism of Captain Parsons, commander of the British ship Port Kingston at Kingston Harbour, whom they charged with neglecting to provide them with any sort of assistance. A very different perspective of the role of Port Kingston in the crisis is provided in the account of Dr. Arthur Evans, a medical practitioner aboard the ship. Evans reported that the vessel was overwhelmed with casualties within an hour of the earthquake and that the ship's crew were "unremitting" in providing aid, with Evans himself performing some 200 medical procedures including numerous amputations over the next few days.[26]

- [33] The source erroneously states that Prinz Eitel Friedrich was already in port in New York when the war broke out, a statement disproven by contemporary newspaper reports.[31][32]

- The ship was named after a variety of counties and towns in the United States.[1]

- A crew complement of 203 according to DANFS.[1]

- Actually French crullers

- [52] The source erroneously states that the contract was awarded to Merrill-Stevens; in fact, the USSB rejected all offers.[51]

- [53] The source erroneously describes Otsego as a "twin-screw" vessel.

References

- "Otsego III (Str)". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships (online edition). Naval History and Heritage Command. 2015-08-18.

- "Single Ship Report for "5373878"". Miramar Ship Index. R. B. Hayworth.(subscription required)

- United States Shipping Board 1920. p. 246.

- American Bureau of Shipping 1919. p. 551.

- Johnson 1920. p. 179.

- Stadum 1983. pp. 121–22.

- Stadum 1983. p. 122.

- "No title". The Pittsburgh Post. 1906-06-21. p. 12 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Steamships". The New York Times. 1913-03-10. p. 17 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Ocean Steamships". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 1914-05-11. p. 15 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Ocean Steamers". The Washington Post. 1914-03-20. p. 11 – via Newspapers.com.

- "New Line to Cuba and Jamaica". The Wenatchee Daily World. Wenatchee, Washington. 1910-08-24. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Tours". The Sun. New York. 1912-01-09. p. 16 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Travelers' Guide—Steamships". The New York Times. 1911-08-14. p. 16 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Ocean Steamships". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 1912-04-09. p. 16 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Sources of Canal Supplies". The Canal Record. Vol. I no. 1. Isthmian Canal Commission. 1907-09-04. p. 8 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Supplies for Canal Work". The Canal Record. Vol. VI no. 12. Isthmian Canal Commission. 1912-11-13. p. 100 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Supplies for the Canal". The Canal Record. Vol. VII no. 38. Panama Canal. 1914-05-13. p. 372 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Seven Hundred Persons Killed by Jamaica Quake". Harrisburg Telegraph. 1907-01-19. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- "1,745 Bodies Found" (PDF). The New York Times. 1907-01-21.

- "Prinz Waldemar Ashore". The Hartford Courant. 1907-01-19. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Angered Swettenham". The Washington Post. 1907-01-31 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Single Ship Report for 5614944". Miramar Ship Index. R. B. Haworth.(subscription required)

- "First Boat Due To-Morrow". The New York Times. 1907-01-21. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Refugees Condemn British Officials". The Allentown Leader. 1907-01-23. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- Evans, A.J. (1907-02-09). "Experiences during the recent earthquake in Jamaica". British Medical Journal. 1 (2406): 348. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.2406.348. PMC 2356668. PMID 20763070.

- "Travelers' Guide—Steamships". The New York Times. 1911-03-27. p. 13 – via Newspapers.com.

- "No title". The Star-Independent. Harrisburg, PA. 1914-02-09. p. 9 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Haytien Ex-President in Jamaica". Olean Evening Herald. Olean, NY. 1914-02-10. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- "English Lines Stop Ships to Continent" (PDF). The New York Times. 1914-08-02.

- "Anxiety Felt for Great Ocean Liners". The Decatur Herald. Decatur, IL. 1914-08-05. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- "At the Docks". The Anderson Daily Intelligencer. Anderson, SC. 1914-08-06. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- Stadum 1983. pp. 122–23.

- "German Ships in New York Harbor Guarded by Police". The Coffeyville Daily Journal. 1919-02-06. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- MacLaury, Judson. "DOL Plays Key Role at the Start of World War I". United States Department of Labor. Archived from the original on 2013-07-02.

- Stadum 1983. p. 123.

- United States Department of War 1920. pp. 4974-77.

- United States Department of War 1920. p. 4977.

- United States Department of Commerce 1920. p. 491.

- "Troops Arrive From Marseilles". The Ogden Standard. 1919-04-18. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Wounded Veterans Return". The Gazette Times. 1919-04-19. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Marine Intelligence". The Gazette Times. 1919-05-25. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Argonne Heroes From Jersey Get Rousing Welcome". The Evening World. 1919-05-26. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- "More 311th Boys Coming on Otsego". Trenton Evening Times. 1919-05-23. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Troops Arrive at Charleston Today". The Index-Journal. 1919-07-02. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Ostego [sic] Arrives With Troops at Charleston". The Wilmington Morning Star. 1919-07-03. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Doughnut Champion Here". The New York Times. 1919-08-29. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Champion Cruller Eater With Record of 249 in 24 Hours Arrives Here". The Evening World. 1919-08-28. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- Gleaves 1921. pp. 258-59.

- "Ship Plan". The Cincinnati Enquirer. 1920-02-18. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- United States Shipping Board 1920. p. 130.

- Villard, Howard G., ed. (1920-03-06). "Jacksonville Yard Awarded Repair Contract". The Nautical Gazette. Vol. 98 no. 10. New York: The Nautical Gazette. p. 395.

- "No title (advertisement)". The Nautical Gazette. Vol. 100 no. 23. New York: The Nautical Gazette. 1921-06-04. p. 743.

- Villard, Howard G., ed. (1921-06-18). "Few Bidders for Ex-German Vessels Offered by Board". The Nautical Gazette. Vol. 100 no. 25. New York: The Nautical Gazette. p. 793.

- Hall, Charles H., ed. (1921-06-25). "Foreign Trade". Shipping. Vol. XIII no. 12. New York: Shipping Publishing Co., Inc. p. 24.

- "Along the Waterfront". The Boston Post. 1921-07-03. p. 30 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Along the Waterfront". The Boston Post. 1921-07-09. p. 10 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Shipping and Travel Guide". New York Tribune. 1921-07-18 – via Newspapers.com.

- United States Government 1925. p. 5825.

- Stadum 1983. pp. 123–24.

- Stadum 1983. p. 124.

- "2 Government Ships Rush to Vessel's Aid". Santa Cruz Sentinel. 1934-08-01 – via Newspapers.com.

- Charles 1947. p. 48.

- Stadum 1983. pp. 124–25.

- Stadum 1983. p. 125.

- "Search results for "5234943"". Miramar Ship Index. R. B. Haworth.(subscription required)

Bibliography

Books

- American Bureau of Shipping (1919). 1919 Record of American and Foreign Shipping. New York: American Bureau of Shipping. p. 551.

- American Bureau of Shipping (1922). 1922 Record of American and Foreign Shipping. New York: American Bureau of Shipping. p. 900.

- Charles, Roland W. (1947). Troopships of World War II. Washington, D.C.: The Army Transportation Association. p. 48.

- Gleaves, Albert (1921). A History of the Transport Service. New York: George H. Doran Company. pp. 258–59.

- Johnson, Eads, ed. (1920). Johnson's Steam Vessels of the Atlantic, Gulf and Pacific Coasts. New York: Eads Johnson, M.E. Inc. p. 179.

- United States Department of Commerce (1920). Annual List of Merchant Vessels of the United States For the Year Ended June 30 1919. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. p. 491.

- United States Department of War (1920). War Department Annual Reports, 1919. I (Part 4). Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. pp. 4974–77.

- United States Government (1925). Hearings Before the Select Committee to Inquire into the Operations, Policies, and Affairs of the United States Shipping Board and the United States Emergency Fleet Corporation: Exhibits to Testimony Part F. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Govt. p. 5825.

- United States Shipping Board (1920). Fourth Annual Report of the United States Shipping Board. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. pp. 130, 246.

- This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.

Trade and academic journals

- British Medical Journal

- The Nautical Gazette (New York)

- Shipping (New York)

- The Canal Record (Panama Canal)

- Stadum, Lloyd M. (June 1983). "Otsego, the other Prinz Eitel Friedrich". The Sea Chest. Vol. 16. Seattle, Washington: Puget Sound Maritime Historical Society. pp. 121–25.

Newspapers

- The Allentown Leader (Allentown, PA)

- The Anderson Daily Intelligencer (Anderson, SC)

- The Boston Post

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle

- The Cincinnati Enquirer

- The Coffeyville Daily Journal (Coffeyville, KS)

- The Decatur Herald (Decatur, IL)

- The Evening World (New York)

- The Gazette Times (Pittsburgh, PA)

- Harrisburg Telegraph (Harrisburg, PA)

- The Hartford Courant (Hartford, CT)

- The Index-Journal (Greenwood, SC)

- The Pittsburgh Post

- The New York Times

- New York Tribune

- The Ogden Standard (Ogden, UT)

- Olean Evening Herald (Olean, NY)

- Santa Cruz Sentinel

- The Star-Independent (Harrisburg, PA)

- The Sun (New York)

- Trenton Evening Times

- The Washington Post

- The Wenatchee Daily World (Wenatchee, WA)

- The Wilmington Morning Star

Websites