SS Kamloops

The SS Kamloops was a lake freighter that was part of the fleet of Canada Steamship Lines from its launching in 1924 until it sank with all hands off Isle Royale in Lake Superior on or about 7 December 1927.

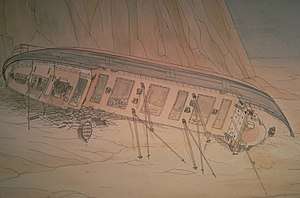

Diagram of Kamloops wreckage | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Kamloops |

| Operator: |

|

| Builder: |

|

| Yard number: | 68 |

| Completed: | 1924 |

| Fate: | Foundered off Isle Royale in western Lake Superior 7 December 1927 |

| Notes: | Canada Registry #147682 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Package freighter – canaller |

| Tonnage: |

|

| Length: | 250 ft (76 m) |

| Beam: | 43 ft (13 m) |

| Height: | 24 ft (7.3 m) |

| Propulsion: | triple expansion steam |

| Crew: | 22 |

KAMLOOPS | |

| |

| Location | Kamloops Point, Isle Royale National Park, Michigan[1] |

| Coordinates | 48°5′6″N 88°45′53″W |

| Area | 45.9 acres (18.6 ha) |

| Built | 1924 |

| Architect | Furness Shipbuilding Company, Ltd. |

| Architectural style | Freighter |

| MPS | Shipwrecks of Isle Royale National Park TR |

| NRHP reference No. | 84001769[2] |

| Added to NRHP | 14 June 1984 |

The canaller

The steamship Kamloops was built by Furness Shipbuilding Co. Ltd.[3] in Haverton Hill within Stockton-on-Tees in the northeast of England for Steamships Ltd of Montreal, Quebec.[4] With a length of only 250 feet (75 m) and rated at 2,402 gross tons,[4] the Kamloops was a relatively small vessel for the Great Lakes in the 1920s.[3] She was built to fit inside the locks of the Welland Canal and other Canadian-operated canals of the lower Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River during the years prior to the construction of the St. Lawrence Seaway.[3] The ship had two rigged masts, and a 1000HP triple expansion steam engine with Scotch boilers.[4]

Kamloops completed its sea testing on 5 July 1924, then shipped to Copenhagen, Denmark to pick up freight, then on to Montreal and Houghton, Michigan.[4] As a canaller, the Kamloops carried diversified "package" freight from Canadian port to port. Her chief duty was carrying manufactured goods from Montreal up the lakes to Thunder Bay.[3] During the 1920s, Canada was part of the British Empire; economically fast-growing areas within the Empire, such as the Prairie Provinces, bought a significant quantity of their manufactured goods from the home country, England. Canada's freshwater fleet, including the Kamloops, was an essential link in this vein of imperial commerce.[5]

It is the custom of Great Lakes shipping to try to move as much freight as possible before winter and associated ice conditions bring boat movements to a halt. The owners operated the ship as late into the season as possible: in 1924 it was one of the last vessels to pass through the Sault Ste. Marie Canal, and in 1926 it ended the season stuck in the ice in the St. Mary's River.[4] The Kamloops remained under British registry until 1926, when it was nominally purchased by new owners, Canada Steamship Lines, and re-registered in Canada.[4]

December 1927

The Kamloops was dispatched up the lakes in late November 1927, carrying a mixed cargo of papermaking machinery, coiled wire for range fencing, shoes, foodstuffs, piping, and tar paper.[3] On 1 December, the steamer called at Courtright, Ontario, to top off its cargo with some bagged salt.[4] It then steamed up Lake Huron, passed through the Sault Ste. Marie Canal on 4 December, and faced the challenge of Lake Superior.

Unfortunately for the Kamloops and other vessels assigned to Lake Superior runs, a massive storm began hammering the lake on 5 December. The Kamloops, heavily coated with ice, was last seen steaming towards the southeastern shore of Isle Royale at dusk on the following day, 6 December.[4] A search for the vessel began on 12 December, concentrating on the Keweenaw Peninsula and Isle Royale; the search continued until 22 December.[4] However, the ship and the 22 men and women aboard were never again seen alive.[5]

When the 1928 navigation season opened in April, a further search was made for wreckage from the Kamloops.[4] In May, fishermen discovered the remains of several crewmembers at Twelve O'Clock Point on Isle Royale (erroneously reported to be on the nearby Amygdaloid Island)[3][4] In addition, wreckage from the ship was discovered ashore.[4] In June, more bodies were discovered, and a more comprehensive search for the wreck and crewmembers was undertaken, but nothing was found.[4]

Of the nine bodies recovered from the Kamloops, five were identified and the remains shipped to next of kin. Four remained unidentified and were buried at Thunder Bay. A collective memorial stone was placed over their gravesite in 2011.[6]

Message in a bottle

In December 1928, a trapper working at the mouth of the Agawa River, Ontario, found a bottled note from Alice Bettridge, an assistant stewardess in her early twenties who initially survived the sinking, and, before she herself perished, wrote "I am the last one left alive, freezing and starving to death on Isle Royale in Lake Superior. I just want mom and dad to know my fate."[7]

The Kamloops today

For fifty years, the Kamloops was one of the Ghost Ships of the Great Lakes, having sunk without a trace.[5] However, on 21 August 1977,[4] her wreck was discovered northwest of Isle Royale, near what is now known as Kamloops Point, by a group of sport divers carrying out a systematic search for the ship.[4] The wreck was discovered sitting on the lake bottom under more than 260 feet (79 m) of water.[8] The ship is lying on its starboard side at the bottom of an underwater cliff.[3] The smokestack has detached and is lying a short distance away, near the starboard aft cargo mast. Cargo is strewn near the ship on the lake floor and the holds still contain wire fencing, high-top shoes, candy life-savers, and crates of Honey Bee molasses.[3] There are still human remains aboard the ship.[3] Approximately 50 dives were made to the Kamloops in 2009 out of 1062 dives made to wrecks in the Isle Royale National Park.[9] The cause of her sinking remained a mystery as of 2007.[3]

The Kamloops features prominently in the novel A Superior Death by Nevada Barr. The body of a contemporary diver is found together with the historical human remains in the ship's engine room.

References

- The wreck is listed as "address restricted", but Isle Royale National Park permits public dives and publishes the location of the wreck. Coordinate location is per "The Wrecks of Isle Royale". Black Dog Diving. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 13 March 2009.

- "The History of the Kamloops". Fridley, Minn: Superior Trips LLC. n.d. Retrieved 13 August 2007.

- Daniel Lenihan; Toni Carrell; Thom Holden; C. Patrick Labadie; Larry Murphy; Ken Vrana (1987), Daniel Lenihan (ed.), Submerged Cultural Resources Study: Isle Royale National Park (PDF), Southwest Cultural Resources Center, pp. 187–209, 326–334

- Dwight Boyer (1968). Ghost Ships of the Great Lakes. New York City, N.Y.: Dodd, Mead & Company. LOC #68-23094.

- "Memorial service to honour S.S. Kamloops sailors". Thunder Bay, Ont.: tbnewswatch.com. 30 November 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- "A shipwreck, a young woman and a message in a bottle". SooToday.com. 26 May 2019. Archived from the original on 12 June 2019.

From the archives of the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library.

Handwriting confirmed by parents. - "Scuba Diving". Isle Royale National Park, National Park Service. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- Pete Sweger (2010), "A Diver's Experience" (PDF), The Greenstone 2010, p. 9

Further reading

- Daniel J. Lenihan (1994), Shipwrecks of Isle Royale National Park: The Archeological Survey, Lake Superior Port Cities, ISBN 0-942235-18-5, archived from the original on 25 November 2010

- Curt Bowen (13 August 2010), "All Hands Lost: Kamloops", Advanced Diver Magazine

- Daniel Lenihan; Toni Carrell; Thom Holden; C. Patrick Labadie; Larry Murphy; Ken Vrana (1987), Daniel Lenihan (ed.), Submerged Cultural Resources Study: Isle Royale National Park, Southwest Cultural Resources Center

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kamloops (ship, 1924). |