Kajaki Dam

The Kajaki Dam is one of the two major hydroelectric power dams of Helmand province in southern Afghanistan. The dam is located on the Helmand River 100 miles (161 km) north-west of Kandahar and is operated by the Helmand and Arghandab Valley Authority. It has a dual function, to provide electricity and to irrigate some 650,000 acres (1800 km²) of an otherwise arid land. Water discharging from the dam traverses some 300 miles (500 km) of downstream irrigation canals feeding farmland. As of October 2016 it produces 52.5 megawatts of electricity.[2]

| Kajaki Dam | |

|---|---|

Aerial view of the Kajaki Dam in 2007 | |

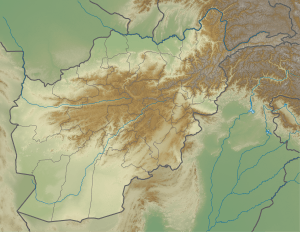

Location of Kajaki Dam in Afghanistan | |

| Country | Afghanistan |

| Location | Kajaki District, Helmand Province |

| Coordinates | 32°19′19″N 65°7′8″E |

| Purpose | Irrigation and electricity |

| Status | Operational |

| Construction began | 1951 |

| Opening date | 1953 |

| Owner(s) | Afghan Ministry of Energy and Water |

| Dam and spillways | |

| Impounds | Helmand River |

| Height | 100 m (328 ft) |

| Length | 270 m (886 ft) |

| Reservoir | |

| Total capacity | 1,715×106 m3 (1,390,373 acre⋅ft) |

| Active capacity | 1,134×106 m3 (919,349 acre⋅ft) |

| Power Station | |

| Operator(s) | Helmand and Arghandab Valley Authority (HAVA) |

| Commission date | 1975 |

| Turbines | 2 x 16.5 MW, 1 x 18.5 MW Francis-type[1] |

| Installed capacity | 52.5 MW |

The dam is 100 m (328 ft) high and 270 m (890 ft) long, with a gross storage capacity of 1,715,000,000 m3 (1,390,373 acre⋅ft) of fresh water. The dam controls the output of the main watershed which feeds the Sistan Basin.

History

Final studies for the dam began in 1946 and a preliminary design was crafted in 1950. The dam was built between 1951 and 1953 by the Morrison-Knudsen firm as part of the Helmand Valley Authority project.[3]

In 1975, USAID commissioned the initial installation of two 16.5 MW generating units in a powerhouse constructed at the toe of the dam. This first stage powerhouse was actually constructed to house three equally sized units. Only units 1 and 3 were installed originally.[3]

When the Soviets invaded Afghanistan in 1979, the contractors left. They had intended to raise the dam by 2 meters in order to increase the available water for power production and irrigation. They were also excavating an emergency spillway which was never completed. Gates were also never installed in the service spillway so the dam passes all water in the reservoir above elevation 1033.5 meters. Completion of the spillway gates would increase the total storage capacity of the reservoir by 1,010,000,000 m3 (818,820 acre⋅ft) to 2,725,000,000 m3 (2,209,193 acre⋅ft).[3]

The Kajaki dam powerhouse was a bombing target of the US Air Force during their attack on Afghanistan in October 2001.[4]

With funding from USAID, World Bank and other donors, Units 1 and 3 were fully rehabilitated and the power station had an installed capacity of 33 MW.[5] Unit 1 was operational in September 2005 and Unit 3 in October 2009.[6] The Unit 3 rehabilitation began in May 2006, with a scheduled return to service in early 2007. The new 18.5 MW Unit 2 turbine/generator had been contracted to China Machine Building International Corporation, which is headquartered in Beijing. The work was to be supervised by Montgomery Watson Harza and was planned to be completed by June 2007 but the work was not completed.

In February 2007, the Kajakai Dam was the subject of fighting between coalition forces and Taliban insurgents, as part of Operation Kryptonite.[7] According to the governor of Helmand province, Assadullah Wafa, over 700 Taliban insurgents (including Pakistanis, Chechens and Uzbeks) coming from neighboring Pakistan fought against over 300 coalition troops.[8] Most of the coalition troops were Dutch and British. The number of casualties mentioned varies. The insurgents intended to destroy the dam.[9]

Hydroelectric power expansion plans

Central to the long term energy security and sustained economic growth of south-eastern Afghanistan is the rehabilitation and expansion of the Kajaki hydroelectric power plant. As a critical component of the Southern Electrical Power System, the capacity of the Kajaki plant would be expanded to 51 MW with a future potential for an additional 100 MW.

In late August 2008 a contingent of ISAF and Afghan troops successfully transported the third turbine (Unit 2) from Kandahar to the Kajaki Dam. The operation was British-led and codenamed Operation Oqab Tsuka, meaning "Eagle's Summit" in Pashto.[10]

A BBC report on the unassembled and uninstalled turbine in June 2011 estimated project completion in late 2013.[11] Despite the turbine being delivered onsite in 2008, over 7 years later in September 2015 it had still not been installed, as its installation required 700 tonnes of cement which could not be delivered to the dam due to attacks by the Taliban.[12] In February 2015, USAID anticipated completion in 2016.[13] When the turbine comes online, and when a new grid of power lines are established to distribute the power, it was expected that the dam would be able to provide 51 megawatts of power.[14]

The turbine was finally commissioned in October 2016, adding 18.5 MW of power output. The project reduces reliance on more expensive and dirtier diesel generation, and nearly doubled the amount of renewable energy distributed to Kandahar. The Afghan electric authority assumed full responsibility for operations and maintenance in March 2017.[2]

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers projects

The United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) had several concurrent project plans associated with the Kajaki Dam with a total program amount of approximately $205 million. Together, the projects would improve water flow for irrigation and electric power generation. The first phase would repair the dam's intake structure. The gates did not close, so no maintenance could be performed on the gates or the irrigation outlet tunnels.

The project included the rehabilitation of existing intake structure components: intake bulkhead gate, steel sliding gate, crane, crane hoist assembly, lifting assembly, embedded parts, and hydrology gauge.

The second phase would rehabilitate the three 84-inch roto valves inside the irrigation tunnel and three 84-inch jet valves at the outlet end of the irrigation tunnel. A roto valve is designed to open and close relatively easily, despite high fluid pressure. Jet valves are installed as part of the outlet structure, and decrease the pressure of the water exiting the bottom of the dam, which prevents erosion and scouring. Another part of the project was to evaluate the current condition of inoperable piezometers at the dam and seek bids to repair or replace them.

Southern Electrical Power System

This two-phased project would improve access to electric power for residents of Helmand and Kandahar provinces. The SEPS—Helmand phase included rebuilding the Kajaki Substation; replacing the 20kV line from the Kajaki Substation to Tangi; a new switchyard at Tangi; a new substation at Musa Qal'eh; a new 110kV line from Kajaki Substation to Musa Qal'eh Substation; a new 20kV line from Kajaki Substation to Kajaki Village, and the rebuilding of a 110kV line from Kajaki Substation to Sangin.

The project also included rebuilding the Sangin North Substation, a new substation at Sangin South, rebuilding a 110kV line from Sangin to Durai Junction, and rebuilding a 110kV line from Durai Junction to Lashkar Gah. USACE awarded the project to Perini Management Services, Inc. of Framingham, Mass., with a 550-day period of performance.

The SEPS-Kandahar project included repairing an existing 110kV line from Durai Junction to Kandahar City, constructing new substations at Maiwand and Pushmool, and upgrading substations at Breshna Kot.

These projects would improve distribution of electrical power to the people of the Lashkar Gah area in Helmand province, and the Kandahar City area.[15]

In October 2017, Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction reported that the project was not complete, and at risk of not being sustained once completed and transferred to the Afghan government.[16]

Water supply accord

Under a monarchy-era accord signed between Iran and Afghanistan in 1972, Afghanistan agreed to release water at a rate of at least 910 cubic feet per second (26 m3/s). In 1998, when Iran threatened to attack in retaliation for the killing of Iranians who were claimed to be diplomats in Mazari Sharif when the Taliban retook that city from the Northern Alliance the second time, the Taliban briefly stopped the flow of water to Iran, using a canal to divert the Helmand's flow southward into the Gowd Zerrah Depression. During that time the Helmand valley was going through a five-year drought. As a result, Iran's Hamun-e Helmand lake dried up, as did regional pastures, leading to the death of flora, fauna, cattle and birds in the Sistan and Baluchestan Province of Iran.[17]

In film

- The American effort to build the dam is mentioned in Adam Curtis's 2015 documentary Bitter Lake.[18] According to the film, the dam caused a salinization of the fields allowing the cultivation of opium.

- Kajaki is a 2014 British war docu-drama film based on the true story of a small unit of British soldiers positioned near the Kajaki dam.

See also

References

![]()

- "Hydroelectric Power Plants in Afghanistan". IndustCards. Archived from the original on 6 December 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- "INSTALLATION OF TURBINE GENERATOR UNIT 2 AT KAJAKI DAM HYDROPOWER PLANT". USAID. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- "Kajakai Hydroelectric Project Condition Assessment Dam Safety Assessment Report" (PDF). Amherst, New York: Acres International Corporation. April 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-08. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- "Kajakai list as October 31, 2002 aerial bombing location". Archived from the original on November 10, 2016. Retrieved July 29, 2006.

- "Afghanistan: Infrastructure" (PDF). USAID. July 2007. Retrieved 2008-10-07.

- "Kajakai Dam Powerhouse Boosts Power to 33 MW, Benefitting Thousands in SW Afghanistan". Afghanistan IRP (Louis Berger Group, Inc.). 24 October 2009. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- Taliban flee battle using children as shields - NATO, February 14, 2007

- US defense secretary in Pakistan, February 12, 2007

- Hundreds of Taliban massing to attack dam - official

- British Troops Complete Operation to Deliver Turbine

- "What went wrong with Afghanistan Kajaki power project?". BBC News report by Mark Urban. Retrieved 2011-06-28.

- The Guardian *with Additional reporting by Rauf Mehrpoor (2015-09-18). "British engineers evacuated from key Afghan dam as Taliban approach". The Guardian. Retrieved 2015-09-18.

- "Installation of Turbine Generator Unit 2 at Kajaki Dam Hydropower Plant (Kajaki Unit 2)". U.S. AID. 3 February 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- UK Troops in Huge Turbine Mission

- Marshall, Karla (25 June 2012). "Corps of Engineers to improve access to water, power in southern Afghanistan". Press Release, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- "Afghanistan Infrastructure Fund: Agencies Have Not Assessed Whether Six Projects That Began in Fiscal Year 2011, Worth about $400 Million, Achieved Counterinsurgency Objectives and Can Be Sustained" (PDF). SIGAR. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- Hirmand River's water to flow into Iran again, soon: Afghan source, December 12, 2002

- Boone, Jon (30 January 2015). "Adam Curtis's Bitter Lake, review: a Carry On Up the Khyber view of Afghanistan". The Spectator. London. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kajaki Dam. |