Solar Energy Generating Systems

Solar Energy Generating Systems (SEGS) is a concentrated solar power plant in California, United States. With the combined capacity from three separate locations at 354 megawatt (MW), it is the world's second largest solar thermal energy generating facility, after the commissioning of the even larger Ivanpah facility in 2014. It consists of nine solar power plants in California's Mojave Desert, where insolation is among the best available in the United States. SEGS I–II (44 MW) are located at Daggett (34°51′45″N 116°49′45″W), SEGS III–VII (150 MW) are installed at Kramer Junction (35°00′43″N 117°33′32″W), and SEGS VIII–IX (160 MW) are placed at Harper Lake (35°01′55″N 117°20′50″W).[1] NextEra Energy Resources operates and partially owns the plants located at Kramer Junction. On January 26, 2018, the SEGS VIII and IX at Harper Lake were sold to renewable energy company Terra-Gen, LLC. A tenth plant (SEGS X, 80 MW) had been in construction and SEGS XI and SEGS XII had been planned by Luz Industries, but the developer filed for bankruptcy in 1992, because it was unable to secure construction financing.[2]

| Solar Energy Generating Systems | |

|---|---|

Part of the 354 MW SEGS solar complex in northern San Bernardino County, California. | |

| |

| Country | United States |

| Location | Mojave Desert |

| Coordinates | 35.0316°N 117.348°W |

| Status | Operational |

| Construction began | 1983 |

| Commission date | 1984 |

| Owner(s) | NextEra Energy Resources |

| Solar farm | |

| Type | CSP |

| CSP technology | Parabolic trough |

| Collectors | 936,384 |

| Site resource | 2,725 kWh/m2/yr |

| Site area | 1,600 acres (647.5 ha) |

| Power generation | |

| Units operational | 9 |

| Units cancelled | 3 |

| Units decommissioned | 1 |

| Nameplate capacity | 361 MW |

| Capacity factor | 19.2% |

| Annual net output | 539 GW·h (2015) |

Plants' scale and operations

The plants have a 354 MW net (394 MW gross) installed capacity. The nameplate capacity, which operating continuously, would dеliver the samе net power output, coming only from the solar source is around 75 MWe —, representing a 21% capacity factor. In addition, the turbines can be utilized at night by burning natural gas.

NextEra claims that the solar plants power 232,500 homеs (during the day, at peak power) and displace 3,800 tons of pollution pеr year that would have been produced if the electricity had bееn providеd by fossil fuels, such as oil.[3]

The facilities have a total of 936,384 mirrors and cover more than 1,600 acres (647.5 ha). Lined up, the parabolic mirrors would extend over 229 miles (369 km).

As an example of cost, in 2002, one of the 30 MW Kramer Junction sites required $90 million to construct, and its operation and maintenance cost was about $3 million per year (4.6 cents per kilowatt hour).[4] With a considered lifetime of 20 years, the operation, maintenance and investments interest and depreciation triples the price, to approximately 14 cents per kilowatt hour.

Principle of operation

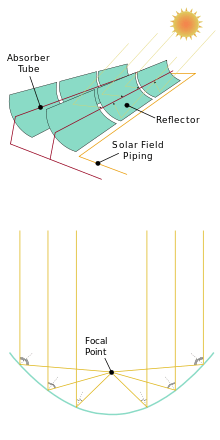

The installation uses parabolic trough, solar thermal technology along with natural gas to generate electricity. About 90% of the electricity is produced by the sunlight. Natural gas is only used when the solar power is insufficient to meet the demand from Southern California Edison, the distributor of power in southern California.[5]

Mirrors

The parabolic mirrors are shaped like quarter-pipes. The sun shines onto the panels made of glass, which are 94% reflective, unlike a typical mirror, which is only 70% reflective. The mirrors automatically track the sun throughout the day. The greatest source of mirror breakage is wind, with 3,000 mirrors typically replaced each year. Operators can turn the mirrors to protect them during intense wind storms. An automated washing mechanism is used to periodically clean the parabolic reflective panels. The term "field area" is assessed as the actual collector area.

Heat transfer

The sunlight bounces off the mirrors and is directed to a central tube filled with synthetic oil, which heats to over 400 °C (750 °F). The reflected light focused at the central tube is 71 to 80 times more intense than the ordinary sunlight. The synthetic oil transfers its heat to water, which boils and drives the Rankine cycle steam turbine,[6] thereby generating electricity. Synthetic oil is used to carry the heat (instead of water) to keep the pressure within manageable parameters.

Individual locations

The SEGS power plants were built by Luz Industries,[6][7] and commissioned between December 20, 1984 and October 1, 1990.[8] After Luz Industries' bankruptcy in 1991 plants were sold to various investor groups as individual projects, and expansion including three more plants was halted.[2]

Kramer Junction employs about 95 people and 45 people work at Harper Lake.

| Plant | Year built |

Location | Turbine capacity |

Field area |

Oil temperature |

Gross solar production of electricity (MWh) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net (MW) | Gross (MW) | (m²) | (°C) | 1985 | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 | 1989 | 1990 | |||

| SEGS I | 1984 | Daggett | 14 | 14 | 82,960 | 307 | 19,261 | 22,510 | 25,055 | 16,927 | 23,527 | 21,491 |

| SEGS II | 1985 | Daggett | 30 | 33 | 190,338 | 316 | 25,085 | 23,431 | 38,914 | 43,862 | 39,156 | |

| SEGS III | 1986 | Kramer Jct. | 30 | 33 | 230,300 | 349 | 49,444 | 61,475 | 63,096 | 69,410 | ||

| SEGS IV | 1986 | Kramer Jct. | 30 | 33 | 230,300 | 349 | 52,181 | 64,762 | 70,552 | 74,661 | ||

| SEGS V | 1987 | Kramer Jct. | 30 | 33 | 250,500 | 349 | 62,858 | 65,280 | 72,449 | |||

| SEGS VI | 1988 | Kramer Jct. | 30 | 35 | 188,000 | 390 | 48,045 | 62,690 | ||||

| SEGS VII | 1988 | Kramer Jct. | 30 | 35 | 194,280 | 390 | 38,868 | 57,661 | ||||

| SEGS VIII | 1989 | Harper Lake | 80 | 89 | 464,340 | 390 | 114,996 | |||||

| SEGS IX | 1990 | Harper Lake | 80 | 89 | 483,960 | 390 | 5,974 | |||||

| Total | 354 | 394 | 2,314,978 | 19,261 | 47,595 | 150,111 | 244,937 | 353,230 | 518,487 | |||

| Sources: Solargenix Energy,[9] KJC Operating Company,[10] IEEE,[11] NREL[12][13] | ||||||||||||

| Gross solar production of electricity (MWh) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | average 1998–2002 | Total |

| SEGS I | 20,252 | 17,938 | 20,368 | 20,194 | 19,800 | 19,879 | 19,228 | 18,686 | 11,250 | 17,235 | 17,947 | 17,402 | 16,500 | 331,550 |

| SEGS II | 35,168 | 32,481 | 36,882 | 36,566 | 35,853 | 35,995 | 34,817 | 33,836 | 33,408 | 31,207 | 32,497 | 31,511 | 32,500 | 549,159 |

| SEGS III | 60,134 | 48,702 | 58,248 | 56,892 | 56,663 | 64,170 | 64,677 | 70,598 | 70,689 | 65,994 | 69,369 | 66,125 | 68,555 | 995,686 |

| SEGS IV | 64,600 | 51,007 | 58,935 | 57,795 | 54,929 | 61,970 | 64,503 | 71,635 | 71,142 | 63,457 | 64,842 | 70,313 | 68,278 | 1,017,283 |

| SEGS V | 59,009 | 55,383 | 67,685 | 66,255 | 63,757 | 71,439 | 75,936 | 75,229 | 70,293 | 73,810 | 71,826 | 73,235 | 72,879 | 1,014,444 |

| SEGS VI | 64,155 | 47,087 | 55,724 | 56,908 | 63,650 | 71,409 | 70,019 | 67,358 | 71,066 | 68,543 | 67,339 | 64,483 | 67,758 | 878,476 |

| SEGS VII | 58,373 | 46,940 | 54,110 | 53,251 | 61,220 | 70,138 | 69,186 | 67,651 | 66,258 | 64,195 | 64,210 | 62,196 | 65,048 | 834,986 |

| SEGS VIII | 102,464 | 109,361 | 130,999 | 134,578 | 133,843 | 139,174 | 136,410 | 137,905 | 135,233 | 140,079 | 137,754 | 138,977 | 137,990 | 1,691,773 |

| SEGS IX | 144,805 | 129,558 | 130,847 | 137,915 | 138,959 | 141,916 | 139,697 | 119,732 | 107,513 | 128,315 | 132,051 | 137,570 | 125,036 | 1,594,852 |

| Total | 608,960 | 538,458 | 613,798 | 620,358 | 628,674 | 676,091 | 674,473 | 662,631 | 636,851 | 652,835 | 657,834 | 662,542 | 654,539 | 8,967,123 |

| Sources: Solargenix Energy,[9] KJC Operating Company,[10] IEEE,[11] NREL[12][13] | ||||||||||||||

| Net solar production of electricity (MWh) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | average 2003–2014 | Total |

| SEGS I | 6,913 | 8,421 | 6,336 | 5,559 | 0 | 10,705 | 9,033 | 10,648 | 11,164 | 11,666 | 9,403 | 8,583 | 8,203 | 98,431 |

| SEGS II | 11,142 | 14,582 | 13,375 | 7,547 | 5,445 | 28,040 | 18,635 | 22,829 | 26,198 | 25,126 | 23,173 | 7,611 | 16,975 | 203,703 |

| SEGS III | 59,027 | 64,413 | 56,680 | 51,721 | 59,480 | 69,012 | 62,971 | 60,029 | 61,350 | 56,877 | 56,824 | 54,407 | 59,399 | 712,791 |

| SEGS IV | 58,100 | 62,006 | 56,349 | 52,439 | 59,799 | 69,338 | 63,563 | 63,084 | 57,684 | 62,414 | 58,317 | 54,321 | 59,785 | 717,414 |

| SEGS V | 61,921 | 67,717 | 62,309 | 53,471 | 59,547 | 69,316 | 59,820 | 54,328 | 60,451 | 62,877 | 57,758 | 56,354 | 60,489 | 725,869 |

| SEGS VI | 50,504 | 53,618 | 51,827 | 45,076 | 65,832 | 67,156 | 62,750 | 63,576 | 59,327 | 56,082 | 52,539 | 50,547 | 56,570 | 678,834 |

| SEGS VII | 49,154 | 50,479 | 46,628 | 42,050 | 58,307 | 65,185 | 58,950 | 58,836 | 57,378 | 54,147 | 48,183 | 46,762 | 53,005 | 636,059 |

| SEGS VIII | 119,357 | 124,089 | 120,282 | 117,451 | 122,676 | 135,492 | 131,474 | 155,933 | 152,463 | 145,247 | 141,356 | 145,525 | 134,279 | 1,611,345 |

| SEGS IX | 115,541 | 123,605 | 120,915 | 117,310 | 122,699 | 150,362 | 139,756 | 163,899 | 160,506 | 164,203 | 154,082 | 147,883 | 140,063 | 1,680,761 |

| Total | 531,659 | 568,930 | 534,701 | 492,624 | 553,785 | 664,606 | 606,952 | 653,162 | 646,521 | 638,639 | 601,635 | 571,993 | 588,767 | 7,065,207 |

| Net solar production of electricity (MWh) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | Total | Total 1985–2017 |

| SEGS I[14] | 12,562 | dec. | (PV) | (PV) | 12,562 | 442,543 |

| SEGS II[15] | dec. | dec. | (PV) | (PV) | 0 | 752,862 |

| SEGS III[16] | 52,073 | 46,582 | 44,115 | 43,849 | 186,619 | 1,895,096 |

| SEGS IV[17] | 53,117 | 49,034 | 43,182 | 44,406 | 189,739 | 1,924,436 |

| SEGS V[18] | 52,646 | 50,142 | 43,934 | 47,383 | 194,105 | 2,889,310 |

| SEGS VI[19] | 46,937 | 40,923 | 36,380 | 34,262 | 158,502 | 1,762,847 |

| SEGS VII[20] | 37,771 | 30,480 | 32,601 | 27,956 | 128,808 | 1,642,628 |

| SEGS VIII[21] | 138,149 | 140,849 | 123,451 | 132,871 | 535,320 | 2,863,152 |

| SEGS IX[22] | 145,863 | 142,867 | 131,268 | 137,564 | 557,562 | 3,763,759 |

| Total | 539,118 | 500,877 | 454,931 | 468,291 | 1,963,217 | 17,936,633 |

| Starting 2017, SEGS I was replaced by PV system Sunray 2, and SEGS II by PV system Sunray 3 | ||||||

Harper Lake

SEGS VIII and SEGS IX, located at 35°01′55″N 117°20′50″W, until Ivanpah Solar Power Facility commissioning in 2014, were the largest solar thermal power plants individually and collectively in the world.[23] They were the last, the largest, and the most advanced of the nine plants at SEGS, designed to take advantage of the economies of scale. Construction of the tenth plant in the same locality was halted because of the bankruptcy of Luz Industries. Construction of the approved eleventh and twelfth plants never started. Each of the three planned plants had 80 MW of installed capacity.[24] Abengoa Solar recently constructed the 280MW Mojave Solar Project (MSP) adjacent to the SEGS VIII and SEGS IX plants.[25] The MSP also uses concentrating solar thermal trough technology.

Kramer Junction

This location (35°00′48″N 117°33′38″W) receives an average of 340 days of sunshine per year, which makes it an ideal place for solar power generation. The average direct normal radiation (DNR) is 7.44 kWh/m²/day (310 W/m²),[10] one of the best in the nation.

Daggett

SEGS I and II were located at 34°51′47″N 116°49′37″W and owned by Cogentrix Energy (Carlyle Group).[26] SEGS II was shut down in 2014 and was replaced by Sunray 3 (EIA plant code 10438), a 13,8 MW photovoltaic system. SEGS I was shut down one year later and replaced by 20 MW PV system Sunray 2 (EIA plant code 10437).[27][28] Sunray 2 and Sunray 3 started production in 2017 as per EIA data.

Accidents and incidents

In February 1999, a 900,000-US-gallon (3,400 m3) Mineral Oil storage tank exploded at the SEGS I (Daggett) solar power plant, sending flames and smoke into the sky. Authorities were trying to keep flames away from two adjacent containers that held sulfuric acid and sodium hydroxide. The immediate area of 0.5 square miles (1.3 km2) was evacuated.[29]

See also

- List of concentrating solar thermal power companies

- List of photovoltaic power stations

- List of solar thermal power stations

- Renewable energy in the United States

- Renewable portfolio standard

- Solar power

- Solar power plants in the Mojave Desert

- List of largest power stations in the world

- Solana Generating Station

References

- The Energy Blog: About Parabolic Trough Solar

- "Large Solar Energy Projects". California Energy Commission. Archived from the original on 14 July 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- "Solar Electric Generating System" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-12-13.

- "Reducing the Cost of Energy from Parabolic Trough Solar Power Plants", NREL, 2003

- Penn, Ivan. "California invested heavily in solar power. Now there's so much that other states are sometimes paid to take it". www.latimes.com. Retrieved 2019-02-25.

- "Solar thermal power generation". Solel Solar Systems Ltd. Archived from the original on 2008-06-01. Retrieved 2010-09-30.

- Alexis Madrigal (November 16, 2009). "Crimes Against the Future: The Demise of Luz". Inventing Green. Archived from the original on 2011-07-11. Retrieved 30 September 2010.

- Solar Electricity Generation in California

-

Cohen, Gilbert (2006). IEEE May Technical Meeting (ed.). "Nevada First Solar Electric Generating System" (PDF). Las Vegas, Nevada: Solargenix Energy: 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-18. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) -

Frier, Scott (1999). An overview of the Kramer Junction SEGS recent performance (ed.). "Parabolic Trough Workshop" (PDF). Ontario, California: KJC Operating Company. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-10-15. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Kearney, D. (August 1989). "Solar Electric Generating Stations (SEGS)". IEEE Power Engineering Review. IEEE. 9 (8): 4–8. doi:10.1109/MPER.1989.4310850.

-

Price, Hank (2002). Parabolic trough technology overview (ed.). "Trough Technology - Algeria" (PDF). NREL: 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-10-20. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Solar Electric Generating Station IX. NREL

- EIA Electricity Data Browser - SEGS I

- EIA Electricity Data Browser - SEGS II

- EIA Electricity Data Browser - SEGS III

- EIA Electricity Data Browser - SEGS IV

- EIA Electricity Data Browser - SEGS V

- EIA Electricity Data Browser - SEGS VI

- EIA Electricity Data Browser - SEGS VII

- EIA Electricity Data Browser - SEGS VIII

- EIA Electricity Data Browser - SEGS IX

- Jones, J. (2000), "Solar Trough Power Plants", National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Retrieved 2010-01-04.

- California Energy Commission - Large Solar Energy Projects

- Abengoa Solar - The Mojave Solar Project

- SUNRAY/SEGS Archived 2013-05-16 at the Wayback Machine

- California Solar Energy Statistics & Data

- Permit approved for solar facility Archived 2017-02-13 at the Wayback Machine

- Storage Tank at Solar Power Plant in Desert Explodes; Immediate Area Is Evacuated