S10 (classification)

S10, SB9, SM10 are disability swimming classifications used for categorizing swimmers based on their level of disability. Swimmers in this class tend to have minimal weakness affecting their legs, missing feet, a missing leg below the knee or problems with their hips. This class includes a number of different disabilities including people with amputations and cerebral palsy. The classification is governed by the International Paralympic Committee, and competes at the Paralympic Games.

Definition

This classification is for swimming.[1] In the classification title, S represents Freestyle, Backstroke and Butterfly strokes. SB means breaststroke. SM means individual medley.[1] Swimming classifications are on a gradient, with one being the most severely physically impaired to ten having the least amount of physical disability.[2] Jane Buckley, writing for the Sporting Wheelies, describes the swimmers in this classification as having: "very minimal weakness affecting the legs; Swimmers with restriction of hip joint movement; Swimmers with both feet deformed; Swimmers with one leg amputated below the knee; Swimmers missing one hand. This is the class with the most physical ability."[1] In 1997, Against the odds : New Zealand Paralympians said this classification was graded along a gradient, with S1 being the most disabled and S10 being the least disabled. At this time, competitors who were S10 classified tended to be below the elbow or below the knee amputees.[3] The Yass Tribune defined this classification in 2007 as "Athletes with a significant range of muscular tone and movement".[4]

Disability types

This class includes people with several disability types include cerebral palsy and amputations.[5][6][7]

Amputee

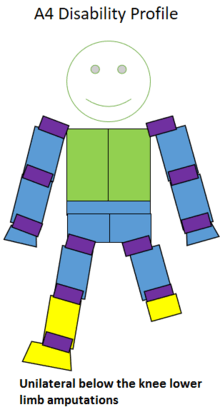

ISOD amputee A4 swimmers may be found in this class.[7] Prior to the 1990s, the A4 class was often grouped with other amputee classes in swimming competitions, including the Paralympic Games.[8] Because they have only a single leg, they have less area on a swimming starting block. The balance issues associated with this can make it more challenging to use a traditional starting position to enter the water.[9] Swimmers in this class have a similar stroke length and stroke rate to able bodied swimmers.[10]

A study of was done comparing the performance of swimming competitors at the 1984 Summer Paralympics. It found there was no significant difference in performance in times between women in A4, A5 and A6 the 100 meter 100 meter freestyle, men in A4 and A5 in the 100 meter freestyle, men and women in A2, A3 and A4 in the 25 meter butterfly, women in A4, A5 and A6 in the 4 x 50 meter individual medley, and men and women in A4, A5 and A6 in the 100 meter backstroke.[8]

The nature of a person's amputations in this class can effect their physiology and sports performance.[11][12][13] Because of the potential for balance issues related to having an amputation, during weight training, amputees are encouraged to use a spotter when lifting more than 15 pounds (6.8 kg).[11] Lower limb amputations affect a person's energy cost for being mobile. To keep their oxygen consumption rate similar to people without lower limb amputations, they need to walk slower.[13] People in this class use around 7% more oxygen to walk or run the same distance as some one without a lower limb amputation.[13]

Cerebral palsy

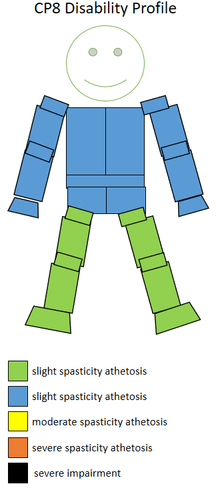

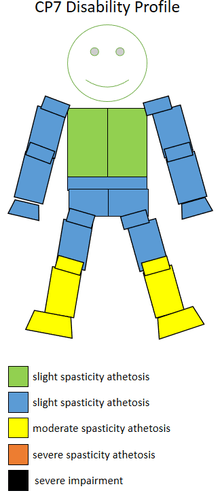

This class includes people with several disability types include cerebral palsy. CP7 and CP8 class swimmers are sometimes found in this class.[5][14] CP7 sportspeople are able to walk, but appear to do so while having a limp as one side of their body is more effected than the other.[15][16][17][18] They may have involuntary muscles spasms on one side of their body.[17][18] They have fine motor control on their dominant side of the body, which can present as asymmetry when they are in motion.[17][19] People in this class tend to have energy expenditure similar to people without cerebral palsy.[20]

Because of the neuromuscular nature of their disability, CP7 and CP8 swimmers have slower start times than other people in their classes.[5] They are also more likely to interlock their hands when underwater in some strokes to prevent hand drift, which increases drag while swimming.[5] CP8 swimmers experience swimmers shoulder, a swimming related injury, at rates similar to their able-bodied counterparts.[5] When fatigued, asymmetry in their stroke becomes a problem for swimmers in this class.[5] The integrated classification system used for swimming, where swimmers with CP compete against those with other disabilities, is subject to criticisms has been that the nature of CP is that greater exertion leads to decreased dexterity and fine motor movements. This puts competitors with CP at a disadvantage when competing against people with amputations who do not lose coordination as a result of exertion.[21]

CP7 swimmers tend to have a passive normalized drag in the range of 0.6 to 0.8. This puts them into the passive drag band of PDB6, PDB8, and PDB9.[22] CP8 swimmers tend to have a passive normalized drag in the range of 0.4 to 0.9. This puts them into the passive drag band of PDB6, PDB8, and PDB10.[23]

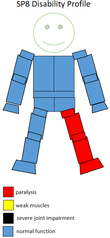

Spinal cord injuries

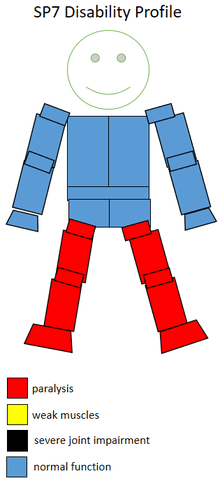

People with spinal cord injuries compete in this class, including F7 and F8 sportspeople.[24][25][26]

F7

F7 is wheelchair sport classification, that corresponds to the neurological level S1- S2.[27][28] Historically, this class has been called Lower 5.[27][28] In 2002, USA Track & Field defined this class as, " These athletes also have the ability to move side to side, so they can throw across their body. They usually can bend one hip backward to push the thigh into the chair, and can bend one ankle downward to push down with the foot. Neurological level: S1-S2."[29]

People with a lesion at S1 have their hamstring and peroneal muscles effected. Functionally, they can bend their knees and lift their feet. They can walk on their own, though they may require ankle braces or orthopedic shoes. They can generally change in any physical activity.[25] People with lesions at the L4 to S2 who are complete paraplegics may have motor function issues in their gluts and hamstrings. Their quadriceps are likely to be unaffected. They may be absent sensation below the knees and in the groin area.[30]

Disabled Sports USA defined the functional definition of this class in 2003 as, "Have very good sitting balance and movements in the backwards and forwards plane. Usually have very good balance and movements towards one side (side to side movements) due to presence of one functional hip abductor, on the side that movement is towards. Usually can bend one hip backwards; i.e. push the thigh into the chair. Usually can bend one ankle downwards; ie. push the foot onto the foot plate. The side that is strong is important when considering how much it will help functional performance."[27]

F7 swimmers competing as S10 tend to have lesions at S1 or S2 that has minimal effect on their lower limbs. This is often caused by polio or cauda-equina syndrome. Swimmers in this class lack full propulsion in their kicks because of a slight loss of function in one limb. They do a standing start and kick turns, but get less power than they might otherwise because of the leg impairment.[31]

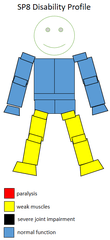

F8

F8 is standing wheelchair sport class.[27][32] The level of spinal cord injury for this class involves people who have incomplete lesions at a slightly higher level. This means they can sometimes bear weight on their legs.[33] In 2002, USA Track & Field defined this class as, "These are standing athletes with dynamic standing balance. Able to recover in standing when balance is challenged. Not more than 70 points in legs."[34] In 2003, Disabled Sports USA defined this class as, "In a sitting class but not more than 70 points in the lower limbs. Are unable to recover balance in challenged standing position."[27] In Australia, this class means combined lower plus upper limb functional problems. "Minimal disability."[35] It can also mean in Australia that the athlete is "ambulant with moderately reduced function in one or both lower limbs."[35] They have a normalized drag in the range of 0.6 to 0.7.[36]

Events

Swimming races available to people in this class include the 50m and 100m Freestyle, 400m Freestyle, 100m Backstroke, 100m Butterfly, 100m Breaststroke and 200m Individual Medley events.[37]

History

The classification was created by the International Paralympic Committee and has roots in a 2003 attempt to address "the overall objective to support and co-ordinate the ongoing development of accurate, reliable, consistent and credible sport focused classification systems and their implementation."[38]

Paralympic Games

For this classification, organisers of the Paralympic Games have the option of including the following events on the Paralympic programme: 50m and 100m Freestyle, 400m Freestyle, 100m Backstroke, 100m Butterfly, 100m Breaststroke and 200m Individual Medley events.[37]

For the 2016 Summer Paralympics in Rio, the International Paralympic Committee had a zero classification at the Games policy. This policy was put into place in 2014, with the goal of avoiding last minute changes in classes that would negatively impact athlete training preparations. All competitors needed to be internationally classified with their classification status confirmed prior to the Games, with exceptions to this policy being dealt with on a case by case basis.[39]

Classification process

Classification generally has four stages. The first stage of classification is a health examination. For amputees in this class, this is often done on site at a sports training facility or competition. The second stage is observation in practice, the third stage is observation in competition and the last stage is assigning the sportsperson to a relevant class.[40] Sometimes the health examination may not be done on site for amputees in this class because the nature of the amputation could cause not physically visible alterations to the body.[41]

In Australia, to be classified in this category, athletes contact the Australian Paralympic Committee or their state swimming governing body.[42] In the United States, classification is handled by the United States Paralympic Committee on a national level. The classification test has three components: "a bench test, a water test, observation during competition."[43] American swimmers are assessed by four people: a medical classified, two general classified and a technical classifier.[43]

Records

Aurélie Rivard of Canada holds both world records in the women's s10 50m freestyle and the women's s10 100m freestyle, both on Long Course.[44] Brazil's Andre Brasil also holds both the men's s10 50m freestyle and the men's s10 100m freestyle world record, on Long Course as well.

Competitors

Swimmers who have competed in this classification include Robert Welbourn, Michael Anderson,[45] Andre Brasil[45] and Anna Eames[45] who all won medals in their class at the 2008 Paralympics.[45]

American swimmers who have been classified by the United States Paralympic Committee as being in this class include Don Alexander, Abbie Argo, Noah Patton and David Prince.[46]

References

- Buckley, Jane (2011). "Understanding Classification: A Guide to the Classification Systems used in Paralympic Sports". Archived from the original on 11 April 2011. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- Shackell, James (2012-07-24). "Paralympic dreams: Croydon Hills teen a hotshot in pool". Maroondah Weekly. Archived from the original on 2012-12-04. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- Gray, Alison (1997). Against the odds : New Zealand Paralympians. Auckland, N.Z.: Hodder Moa Beckett. p. 18. ISBN 1869585666. OCLC 154294284.

- "Aaron Rhind sets record straight". Yass Tribune. 2007-10-24. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- Scott, Riewald; Scott, Rodeo (2015-06-01). Science of Swimming Faster. Human Kinetics. ISBN 9780736095716.

- Tim-Taek, Oh; Osborough, Conor; Burkett, Brendan; Payton, Carl (2015). "Consideration of Passive Drag in IPC Swimming Classification System" (PDF). VISTA Conference. International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- Tim-Taek, Oh; Osborough, Conor; Burkett, Brendan; Payton, Carl (2015). "Consideration of Passive Drag in IPC Swimming Classification System" (PDF). VISTA Conference. International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- van Eijsden-Besseling, M. D. F. (1985). "The (Non)sense of the Present-Day Classification System of Sports for the Disabled, Regarding Paralysed and Amputee Athletes". Paraplegia. International Medical Society of Paraplegia. 23. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- Vanlandewijck, Yves C.; Thompson, Walter R. (2016-06-01). Training and Coaching the Paralympic Athlete. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781119045120.

- Vanlandewijck, Yves C.; Thompson, Walter R. (2011-07-13). Handbook of Sports Medicine and Science, The Paralympic Athlete. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781444348286.

- "Classification 101". Blaze Sports. Blaze Sports. June 2012. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- DeLisa, Joel A.; Gans, Bruce M.; Walsh, Nicholas E. (2005-01-01). Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: Principles and Practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780781741309.

- Miller, Mark D.; Thompson, Stephen R. (2014-04-04). DeLee & Drez's Orthopaedic Sports Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9781455742219.

- Tim-Taek, Oh; Osborough, Conor; Burkett, Brendan; Payton, Carl (2015). "Consideration of Passive Drag in IPC Swimming Classification System" (PDF). VISTA Conference. International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- "CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM FOR STUDENTS WITH A DISABILITY". Queensland Sport. Queensland Sport. Archived from the original on April 4, 2015. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- "Classification Made Easy" (PDF). Sportability British Columbia. Sportability British Columbia. July 2011. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- "Clasificaciones de Ciclismo" (PDF). Comisión Nacional de Cultura Física y Deporte (in Spanish). Mexico: Comisión Nacional de Cultura Física y Deporte. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- "Kategorie postižení handicapovaných sportovců". Tyden (in Czech). September 12, 2008. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- Cashman, Richmard; Darcy, Simon (2008-01-01). Benchmark Games. Benchmark Games. ISBN 9781876718053.

- Broad, Elizabeth (2014-02-06). Sports Nutrition for Paralympic Athletes. CRC Press. ISBN 9781466507562.

- Richter, Kenneth J.; Adams-Mushett, Carol; Ferrara, Michael S.; McCann, B. Cairbre (1992). "llntegrated Swimming Classification : A Faulted System" (PDF). Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly. 9: 5–13. doi:10.1123/apaq.9.1.5.

- Tim-Taek, Oh; Osborough, Conor; Burkett, Brendan; Payton, Carl (2015). "Consideration of Passive Drag in IPC Swimming Classification System" (PDF). VISTA Conference. International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- Tim-Taek, Oh; Osborough, Conor; Burkett, Brendan; Payton, Carl (2015). "Consideration of Passive Drag in IPC Swimming Classification System" (PDF). VISTA Conference. International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- International Paralympic Committee (February 2005). "SWIMMING CLASSIFICATION CLASSIFICATION MANUAL" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee Classification Manual. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04.

- Winnick, Joseph P. (2011-01-01). Adapted Physical Education and Sport. Human Kinetics. ISBN 9780736089180.

- Tim-Taek, Oh; Osborough, Conor; Burkett, Brendan; Payton, Carl (2015). "Consideration of Passive Drag in IPC Swimming Classification System" (PDF). VISTA Conference. International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- National Governing Body for Athletics of Wheelchair Sports, USA. Chapter 2: Competition Rules for Athletics. United States: Wheelchair Sports, USA. 2003.

- Consejo Superior de Deportes (2011). Deportistas sin Adjectivos (PDF) (in Spanish). Spain: Consejo Superior de Deportes. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04. Retrieved 2016-08-03.

- "SPECIAL SECTION ADAPTATIONS TO USA TRACK & FIELD RULES OF COMPETITION FOR INDIVIDUALS WITH DISABILITIES" (PDF). USA Track & Field. USA Track & Field. 2002.

- Goosey-Tolfrey, Vicky (2010-01-01). Wheelchair Sport: A Complete Guide for Athletes, Coaches, and Teachers. Human Kinetics. ISBN 9780736086769.

- International Paralympic Committee (February 2005). "SWIMMING CLASSIFICATION CLASSIFICATION MANUAL" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee Classification Manual. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04.

- Consejo Superior de Deportes (2011). Deportistas sin Adjectivos (PDF) (in Spanish). Spain: Consejo Superior de Deportes. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04. Retrieved 2016-08-03.

- Foster, Mikayla; Loveridge, Kyle; Turley, Cami (2013). "S P I N A L C ORD I N JURY" (PDF). Therapeutic Recreation.

- "SPECIAL SECTION ADAPTATIONS TO USA TRACK & FIELD RULES OF COMPETITION FOR INDIVIDUALS WITH DISABILITIES" (PDF). USA Track & Field. USA Track & Field. 2002.

- Sydney East PSSA (2016). "Para-Athlete (AWD) entry form – NSW PSSA Track & Field". New South Wales Department of Sports. New South Wales Department of Sports. Archived from the original on 2016-09-28.

- Tim-Taek, Oh; Osborough, Conor; Burkett, Brendan; Payton, Carl (2015). "Consideration of Passive Drag in IPC Swimming Classification System" (PDF). VISTA Conference. International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- "Swimming Classification". The Beijing Organizing Committee for the Games of the XXIX Olympiad. 2008. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- "Paralympic Classification Today". International Paralympic Committee. 22 April 2010. p. 3. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - "Rio 2016 Classification Guide" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee. International Paralympic Committee. March 2016. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- Tweedy, Sean M.; Beckman, Emma M.; Connick, Mark J. (August 2014). "Paralympic Classification: Conceptual Basis, Current Methods, and Research Update". Paralympic Sports Medicine and Science. 6 (85). Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- Gilbert, Keith; Schantz, Otto J.; Schantz, Otto (2008-01-01). The Paralympic Games: Empowerment Or Side Show?. Meyer & Meyer Verlag. ISBN 9781841262659.

- "Classification Information Sheet" (PDF). Australian Paralympic Committee. 8 March 2011. p. 3. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- "U.S. Paralympics National Classification Policies & Procedures SWIMMING". United States Paralympic Committee. 26 June 2011. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- "Parapan Am world record". Swimming Canada. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- "Results". International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- "USA NATIONAL CLASSIFICATION DATABASE" (PDF). United States Paralympic Committee. 7 October 2011. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

.svg.png)