F8 (classification)

F8, also SP8, is a standing wheelchair sport classification open to people with spinal cord injuries, with inclusion based on a functional classification on a points system for lower limb functionality. Sportspeople in this class need to have less than 70 points. The class has largely been used in Australia and the United States. F8 has largely been eliminated because of a perceived lack of need internationally for a standing wheelchair class. Sports this class participates in include athletics, swimming and wheelchair basketball. In athletics, participation is mostly in field events.

Definition

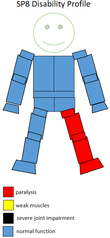

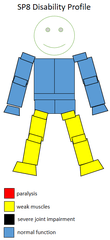

F8 is standing wheelchair sport class.[1][2] The level of spinal cord injury for this class involves people who have incomplete lesions at a slightly higher level. This means they can sometimes bear weight on their legs.[3] In 2002, USA Track & Field defined this class as, "These are standing athletes with dynamic standing balance. Able to recover in standing when balance is challenged. Not more than 70 points in legs."[4] In 2003, Disabled Sports USA defined this class as, "In a sitting class but not more than 70 points in the lower limbs. Are unable to recover balance in challenged standing position."[1] In Australia, this class means combined lower plus upper limb functional problems. "Minimal disability."[5] It can also mean in Australia that the athlete is "ambulant with moderately reduced function in one or both lower limbs."[5] In Australia, the corresponding class for based on disability type classes are A2, A3, A9, and LAF5.[5]

History

During the 1960s and 1970s, classification involved being examined in a supine position on an examination table, where multiple medical classifiers would often stand around the player, poke and prod their muscles with their hands and with pins. The system had no built in privacy safeguards and players being classified were not insured privacy during medical classification nor with their medical records.[6] In the early Paralympic Games, this class would have been ineligible to participate in many cases because they did not meet minimum disability requirements set by the ISMGF.[7]

This class was historically merged in the 2000s with.[1][8] The class was largely used in the United States for domestic competitions during the 2000s for standing wheelchair athletes. Initially, following changes made to the classification system internationally in this period, they were classified as F59 for international purposes. Their class was then changed following international classification. Their new classification was then used domestically. Domestically, they were moved to the F9 class because of a perceived lack internationally to have a standing wheelchair class.[1]

Sports

Athletics

Under the IPC Athletics classification system, this class competes in F42, F43, F44, and F58.[1][2][5] Field events open to this class have included shot put, discus and javelin.[1][2] In pentathlon, the events for this class have included Shot, Javelin, 200m, Discus, 1500m.[1] For F8 javelin throwers, they can throw the javelin from a standing position and they use a javelin that weights .8 kilograms (1.8 lb).[9]

Performance wise, a 1999 study of discus throwers found that for F5 to F8 discus throwers, the upper arm tends to be near horizontal at the moment of release of the discus. F5 and F8 discus throwers have less average angular forearm speed than F2 and F4 throwers. F2 and F4 speed is caused by use of the elbow flexion to compensate for the shoulder flexion advantage of F5 to F8 throwers.[10] A study of javelin throwers in 2003 found that F8 throwers have angular speeds of the shoulder girdle similar to that of F3, F4, F5, F6, F7 and F9 throwers.[9]

Other sports

Two other sports people in this class participate in are wheelchair basketball and swimming.[11][12] In the earliest medical classifications for wheelchair basketball, they would have been ineligible to play.[11] Under the current classification system, they would likely be classified as a 4.5 point player.[13] SP8 swimmers can be found in IPC classes of S8, S9 and S10.[1][14][15][16] They have a normalized drag in the range of 0.6 to 0.7.[12]

Getting classified

Classification is often sport specific, and has two parts: a medical classification process and a functional classification process.[17][18][19]

Medical classification for wheelchair sport can consist of medical records being sent to medical classifiers at the international sports federation. The sportsperson's physician may be asked to provide extensive medical information including medical diagnosis and any loss of function related to their condition. This includes if the condition is progressive or stable, if it is an acquired or congenital condition. It may include a request for information on any future anticipated medical care. It may also include a request for any medications the person is taking. Documentation that may be required my include x-rays, ASIA scale results, or Modified Ashworth Scale scores.[20]

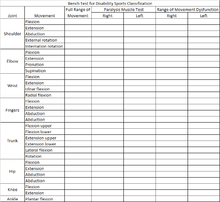

One of the standard means of assessing functional classification is the bench test, which is used in swimming, lawn bowls and wheelchair fencing.[18][17][19] Using the Adapted Research Council measurements, muscle strength is tested using the bench press for a variety of spinal cord related injuries with a muscle being assessed on a scale of 0 to 5. A 0 is for no muscle contraction. A 1 is for a flicker or trace of contraction in a muscle. A 2 is for active movement in a muscle with gravity eliminated. A 3 is for movement against gravity. A 4 is for active movement against gravity with some resistance. A 5 is for normal muscle movement.[18]

References

- National Governing Body for Athletics of Wheelchair Sports, USA. Chapter 2: Competition Rules for Athletics. United States: Wheelchair Sports, USA. 2003.

- Consejo Superior de Deportes (2011). Deportistas sin Adjectivos (PDF) (in Spanish). Spain: Consejo Superior de Deportes. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04. Retrieved 2016-07-28.

- Foster, Mikayla; Loveridge, Kyle; Turley, Cami (2013). "Spinal Cord Injury" (PDF). Therapeutic Recreation.

- "Special Section Adaptations to USA Track & Field Rules of Competition for Individuals with Disabilities" (PDF). USA Track & Field. USA Track & Field. 2002.

- Sydney East PSSA (2016). "Para-Athlete (AWD) entry form – NSW PSSA Track & Field". New South Wales Department of Sports. New South Wales Department of Sports. Archived from the original on 2016-09-28.

- Chapter 4. 4 - Position Statement on background and scientific rationale for classification in Paralympic sport (PDF). International Paralympic Committee. December 2009.

- Chapter 4. 4 - Position Statement on background and scientific rationale for classification in Paralympic sport (PDF). International Paralympic Committee. December 2009.

- "Official Guide & Rules of Games 2006" (PDF). Gaelic Athletics & Cycle Association. 2006.

- Chow, John W.; Kuenster, Ann F.; Lim, Young-tae (2003-06-01). "Kinematic Analysis of Javelin Throw Performed by Wheelchair Athletes of Different Functional Classes". Journal of Sports Science & Medicine. 2 (2): 36–46. ISSN 1303-2968. PMC 3938047. PMID 24616609.

- Chow, J. W., & Mindock, L. A. (1999). Discus throwing performances and medical classification of wheelchair athletes. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise,31(9), 1272-1279. doi:10.1097/00005768-199909000-00007

- Chapter 4. 4 - Position Statement on background and scientific rationale for classification in Paralympic sport (PDF). International Paralympic Committee. December 2009.

- Tim-Taek, Oh; Osborough, Conor; Burkett, Brendan; Payton, Carl (2015). "Consideration of Passive Drag in IPC Swimming Classification System" (PDF). VISTA Conference. International Paralympic Committee. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 16, 2016. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- "Simplified Rules of Wheelchair Basketball and a Brief Guide to the Classification system". Cardiff Celts. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- Consejo Superior de Deportes (2011). Deportistas sin Adjectivos (PDF) (in Spanish). Spain: Consejo Superior de Deportes. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04. Retrieved 2016-07-28.

- Tim-Taek, Oh; Osborough, Conor; Burkett, Brendan; Payton, Carl (2015). "Consideration of Passive Drag in IPC Swimming Classification System" (PDF). VISTA Conference. International Paralympic Committee. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 16, 2016. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- Tweedy, S. M. (2003). The ICF and Classification in Disability Athletics. In R. Madden, S. Bricknell, C. Sykes and L. York (Ed.), ICF Australian User Guide, Version 1.0, Disability Series (pp. 82-88)Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

- "Classification Guide" (PDF). Swimming Australia. Swimming Australia. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 24, 2016.

- "Bench Press Form". International Disabled Bowls. International Disabled Bowls. Retrieved July 29, 2016.

- IWAS (20 March 2011). "IWF Rules for Competition, Book 4 – Classification Rules" (PDF).

- "Medical Diagnostic Form" (PDF). IWAS. IWAS. Retrieved July 30, 2016.