CP1 (classification)

CP1 is a disability sport classification specific to cerebral palsy. In many sports, it is grouped inside other classifications to allow people with cerebral palsy to compete against people with other different disabilities but the same level of functionality. CP1 classified competitors are the group who are most physically affected by their cerebral palsy. They are quadriplegics.

The most popular sport for people in this class is boccia, where they are classified as either BC1 or BC3. Other sports open to competitors in this class include athletics, cycling, race running, slalom, and swimming. In some of these sports, different classification systems or names for CP1 are used.

Definition and participation

CP1 classified competitors are the group who are most physically affected by their cerebral palsy.[1] They are most likely to participate in boccia.[1]

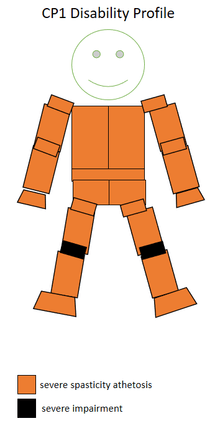

Cerebral Palsy-International Sports and Recreation Association (CP-ISRA) defined this class in January 2005 as, "Quadriplegic (Tetraplegic)-Severe involvement. Spasticity Grade 4 to 3+, with or without athetosis or with poor functional range of movement and poor functional strength in all extremities and trunk OR the severe athetoid with or without spasticity with poor functional strength and control. Dependent on a power wheelchair or assistance for mobility. Unable to functionally propel a wheelchair. Lower Extremities-Considered non-functional in relation to any sport due to limitation in range of movement strength and/or control. Minimal or involuntary movement would not change this person's class. Trunk Control-Static and dynamic trunk control very poor or non-existent. Severe difficulty adjusting back to mid-line or upright position when performing sports movements. Upper Extremities-Severe limitation in functional range of movement or severe athetosis are the major factors in all sports, and reduced throwing motion with poor follow through is evident. Opposition of thumb and one finger may be possible allowing athlete to grip."[2]

Performance

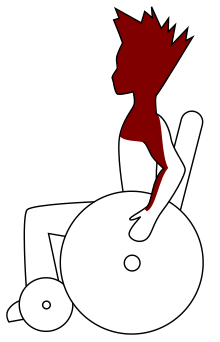

CP1 sportspeople tend to use electric wheelchairs.[3] They may have controlled shakes and twitches.[1][3][4] They have severely limited of their trunk and limbs.[4][5][6] When participating in sport, CP1 competitors tend to have low energy expenditure. This bodily activity can spike their metabolic rate.[1][4] CP1 competitors have worse upper body control when compared to CP2.[7]

Sports

Athletics

The IPC equivalent for this class is F31, and they compete mostly in field events.[2][8] Historically, CP1 athletes were more active in track events. Changes in the classification during the 1980s and 1990s led to most track events for CP1 racers being dropped and replaced exclusively with field events.[9][10] This has been criticized, because with the rise of commercialization of the Paralympic movement, there has been a reduction of classes in more popular sports for people with the most severe disabilities as these classes often have much higher support costs associated with them.[11][12][13]

Boccia

People with cerebral palsy are eligible to compete in boccia at the Paralympic Games.[1][2][14] Boccia made its debut on the Paralympic program at the 1984 Games.[15] Boccia began to develop as an important sport for people in this class as track events began to disappear. The timing of this matched with a push by the CP-ISRA to promote the sport.[9]

CP1 competitors are classified as either BC1 or BC3.[2][16] In BC1, they can generally throw the ball past the V Line.[2][16] They are allowed to have assistants.[3] BC3 players cannot throw the ball themselves, require the use of an electric wheelchair and use a ramp to propel the ball.[2][16]

Cycling

CP1 to CP4 competitors may compete using tricycles in the T1 class.[3][5][17] Tricycles are only eligible to compete in road events, not track ones.[5] Cyclists in this class are required to wear a helmet, with a special color used to designate their class.[3] CP1 cyclists wear a green helmet.[7][18]

Race Running

CP1 sportspeople can compete in race running. CP1 race runners are classified as RR1.[6][16] The classes events include the 100 meters, 200 meters and 400 meters.[16] They often require that their arms or legs be strapped in order for them to run. When they do run, their legs to butterfly out and can inadvertently cross.[2] Compared to other CP race running classes, CP1 and CP2 have a low economy of movement.[19]

Slalom

One of the sports available for CP1 sportspeople is slalom.[14] Slalom involves an obstacle course for people using carts. CP1 competitors can use motorized carts unlike competitors in other CP wheelchair classes.[14]

Swimming

People with cerebral palsy are eligible to compete in swimming at the Paralympic Games.[1][2] CP1 swimmers may be found in several classes. These include S1, and S2.[20] Some swimmers in this class require floaters to race. The use of such devices is not allowed in IPC sanctioned events, but is allowed in CP-ISRA sanctioned ones.[2] CP1 swimmers tend to have a passive normalized drag in the range of 1.3 to 1.7. This puts them into the passive drag band of PDB1, and PDB3.[20]

Classification process

The process for being classified is often sports specific.[21] As a general rule, CP1 need to attend classification in a wheelchair. Failure to do so could result in them being classified as an ambulatory CP class competitor such as CP5 or CP6, or a related sport specific class.[8]

One of the standard means of assessing functional classification is the bench test, which is used in swimming, lawn bowls and wheelchair fencing. Using the Adapted Research Council (MRC) measurements, muscle strength is tested using the bench press for a variety of disabilities a muscle being assessed on a scale of 1 to 5 for people with cerebral palsy and other issues with muscle spasticity. A 1 is for no functional movement of the muscle or where there is no motor coordination. A 2 is for normal muscle movement range not exceeding 25% or where the movement can only take place with great difficult and, even then, very slowly. A 3 is where normal muscle movement range does not exceed 50%. A 4 is when normal muscle movement range does not exceed 75% and or there is slight in-coordination of muscle movement. A 5 is for normal muscle movement.

Swimming classification generally has three components. The first is a bench press. The second is water test. The third is in competition observation.[22] As part of the water test, swimmers are often required to demonstrate their swimming technique for all four strokes. They usually swim a distance of 25 meters for each stroke. They are also generally required to demonstrate how they enter the water and how they turn in the pool.[23]

References

- Broad, Elizabeth (2014-02-06). Sports Nutrition for Paralympic Athletes. CRC Press. ISBN 9781466507562.

- "CLASSIFICATION AND SPORTS RULE MANUAL" (PDF). CPISRA. CPISRA. January 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 15, 2016. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- Hutson, Michael; Speed, Cathy (2011-03-17). Sports Injuries. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780199533909.

- "Kategorie postižení handicapovaných sportovců". Tyden (in Czech). September 12, 2008. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- "Clasificaciones de Ciclismo" (PDF). Comisión Nacional de Cultura Física y Deporte (in Spanish). Mexico: Comisión Nacional de Cultura Física y Deporte. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- "Invitation til DHIF's Atletik Forbunds". Frederiksberg Handicapidræt (in Danish). Frederiksberg Handicapidræt. 2007. Archived from the original on September 16, 2016. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- Hernández García, Jose Ignacio; Vecino, Jorge Manrique; Koszegi, Melinda; Marto, Anabela. "PROGRAMA LEONARDO DA VINCI, TRAINING SPORT ASSISTANTS FOR THE DISABLED" (PDF). Programa Leonardo da Vinci. European Union. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-08-16. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- Cashman, Richmard; Darcy, Simon (2008-01-01). Benchmark Games. Benchmark Games. ISBN 9781876718053.

- Howe, David (2008-02-19). The Cultural Politics of the Paralympic Movement: Through an Anthropological Lens. Routledge. ISBN 9781134440832.

- Loland, Sigmund; Skirstad, Berit; Waddington, Ivan (2006-01-01). Pain and Injury in Sport: Social and Ethical Analysis. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780415357036.

- Hardman, Alun R.; Jones, Carwyn (2010-12-02). The Ethics of Sports Coaching. Routledge. ISBN 9781135282967.

- Brittain, Ian (2016-07-01). The Paralympic Games Explained: Second Edition. Routledge. ISBN 9781317404156.

- Baker, Joe; Safai, Parissa; Fraser-Thomas, Jessica (2014-10-17). Health and Elite Sport: Is High Performance Sport a Healthy Pursuit?. Routledge. ISBN 9781134620012.

- Daďová, Klára; Čichoň, Rostislav; Švarcová, Jana; Potměšil, Jaroslav (2008). "KLASIFIKACE PRO VÝKONNOSTNÍ SPORT ZDRAVOTNĚ POSTIŽENÝCH". Karolinum (in Czech). Prague. Archived from the original on August 17, 2016. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- Whyte, Gregory; Loosemore, Mike; Williams, Clyde (2015-07-27). ABC of Sports and Exercise Medicine. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118777503.

- "Classification Made Easy" (PDF). Sportability British Columbia. Sportability British Columbia. July 2011. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- "Classification Profiles" (PDF). Cerebral Palsy International Sports and Recreation Association. Cerebral Palsy International Sports and Recreation Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-08-18. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- "CAPACITÀ PER LO SPORT`, FORMAZIONE DEGLI OPERATORI SPORTIVI SPECIALIZZATI PER PERSONE CON DISABILITÀ" (PDF). Programa Leonardo da Vinci (in Italian). European Union. September 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-08-17. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- Vanlandewijck, Yves; Van de Vliet, Peter; O’Donnell, Ruairi. "Ergonomic optimization as a basis of performance enhancement in cerebral palsy athletes" (PDF). Retrieved July 19, 2016.

- Tim-Taek, Oh; Osborough, Conor; Burkett, Brendan; Payton, Carl (2015). "Consideration of Passive Drag in IPC Swimming Classification System" (PDF). VISTA Conference. International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- "Classification Profiles" (PDF). Cerebral Palsy International Sports and Recreation Association. Cerebral Palsy International Sports and Recreation Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-08-18. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- "CLASSIFICATION GUIDE" (PDF). Swimming Australia. Swimming Australia. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 24, 2016.

- "Classification Profiles" (PDF). Cerebral Palsy International Sports and Recreation Association. Cerebral Palsy International Sports and Recreation Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-08-18. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

.svg.png)