Russians in Estonia

The population of Russians in Estonia is estimated at 320,000, most of whom live in the urban areas of Harju and Ida-Viru counties. Estonia has a 300-year old history of small-scale settlement by Russian Old Believers along Lake Peipus. The predominant majority of the current Russian population in Estonia originate from the Soviet occupation period immigration.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 320,000 (est.) (24% of total population) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Harju County, Ida-Viru County | |

| Languages | |

| Russian and Estonian | |

| Religion | |

| Russian Orthodox Church |

Early contacts

The Estonian name for Russians vene, venelane derives from an old Germanic loan veneð referring to the Wends, speakers of a Slavic language who lived on the southern coast of the Baltic sea.[1][2]

Prince Yaroslav the Wise of Kievan Rus' defeated Chuds in 1030 and established fort of Yuryev (in modern-day Tartu),[3] which survived until 1061 when the Kievans were driven out by the tribe of Sosols.[4][5]

A medieval proto-Russian settlement was in Kuremäe, Vironia. The Orthodox community in the area built a church in the 16th century and in 1891 the Pühtitsa Convent was created on its site.[6] Proto-Russian cultural influence had its mark on Estonian language, with a number of words such as "turg" (trade) and "rist" (cross) adopted from East Slavic.[7]

In 1217, an allied Ugaunian-Novgorodian army defended the Ugaunian stronghold of Otepää from the German knights. Novgorodian prince Vyachko died in 1224 with all his druzhina defending the fortress of Tarbatu together with his Ugaunian and Sackalian allies against the Livonian Order led by Albert of Riga.

Orthodox churches and small communities of proto-Russian merchants and craftsmen remained in Livonian towns as did close trade links with the Novgorod Republic and the Pskov and Polotsk principalities. In 1481, Ivan III of Russia laid siege to the castle of Fellin (Viljandi) and briefly captured several towns in eastern Livonia in response to a previous attack on Pskov. Between 1558 and 1582, Ivan IV of Russia captured much of mainland Livonia in the midst of the Livonian War but eventually the Russians were driven out by Lithuanian-Polish and Swedish armies. Tsar Alexis I of Russia once again captured towns in eastern Livonia, including Dorpat (Tartu) and Nyslott (Vasknarva) between 1656 and 1661, but had to yield his conquests to Sweden.

17th century to 1940

The beginning of continuous Russian settlement in what is now Estonia dates back to the late 17th century when several thousand Russian Old Believers, escaping religious persecution in Russia, settled in areas then a part of the Swedish empire near the western coast of Lake Peipus.[8]

In the 18th century after the Great Northern War the territories of Estonia divided between the Governorate of Estonia and Livonia became part of the Russian Empire but maintained local autonomy and were administered independently by the local Baltic German nobility through a feudal Regional Council (German: Landtag).[9] The second period of influx of Russians followed the Imperial Russian conquest of the northern Baltic region, including Estonia, from Sweden in 1700–1721. Under Russian rule, power in the region remained primarily in the hands of the Baltic German nobility, but a limited number of administrative jobs was gradually taken over by Russians, who settled in Reval (Tallinn) and other major towns.

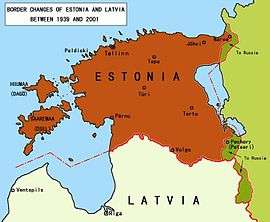

A relatively larger number of ethnic Russian workers settled in Tallinn and Narva during the period of rapid industrial development at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. After the First World War, the share of ethnic Russians in the population of independent Estonia was 7.3%.[10] About half of these were indigenous Russians living in Narva, Ivangorod, the Estonian Ingria and the Petseri County, which were added to Estonia territory according to the 1920 Peace Treaty of Tartu, but were transferred (without Narva) to the Russian SFSR in 1944.

In the aftermath of World War I Estonia became an independent republic where the Russians, comprising 8% of the total population among other ethnic minorities, established Cultural Self-Governments according to the 1925 Estonian Law on Cultural Autonomy.[11] The state was tolerant of the Russian Orthodox Church and became a home to many Russian émigrés after the Russian October Revolution in 1917.[12]

World War II and the Estonian SSR

After the Occupation and annexation of the Baltic states by the Soviet Union in 1940,[13][14] repression of ethnic Estonians followed. According to Sergei Isakov, almost all societies, newspapers, organizations of ethnic Estonians were closed in 1940 and their activists persecuted.[15] The country remained annexed to the Soviet Union until 1991, except for the period of Nazi occupation between 1941 and 1944. During the era of Soviet occupation, the Soviet government maintained a program of replacing the indigenous Estonians with immigrants from the Soviet Union. In the course of violent population transfers, thousands of Estonian citizens were deported to the interior parts of Russia (mostly Siberia), and huge numbers of Russian-speaking Soviet citizens were encouraged to settle in Estonia. In the Ida-Viru and Harju Counties, cities such as Paldiski, Sillamäe, and Narva were ethnically cleansed and the indigenous Estonian population was totally replaced by Russian colonists. As a result of Soviet occupation, the Russian population in Estonia grew from about 23,000 people in 1945 to 475,000 in 1991, and the total Slavic population to 551,000, constituting 35% of the total population at its peak.[16]

In 1939 ethnic Russians had comprised 8% of the population; however, following the annexation of about 2,000 km2 (772 sq mi) of land by the Russian SFSR in January 1945, including Ivangorod (then the eastern suburb of Narva) and the Petseri County, Estonia lost most of its inter-war ethnic Russian population. Of the estimated 20,000 Russians remaining in Estonia, the majority belonged to the historical community of Old Believers.[17]

Most of the present-day Russians in Estonia are recent migrants and their descendants who settled in during the Soviet occupation between 1945 and 1991. Following the terms of the 1939 Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, the Soviet Union occupied and annexed the Baltic States in 1940. The authorities carried out repressions against many prominent ethnic Russians activists and White emigres in Estonia.[18] Many Russians were arrested and executed by different Soviet war tribunals in 1940–1941.[19] After Germany attacked the Soviet Union in 1941, the Baltics quickly fell under German control. Many Russians, especially Communist party members who had arrived in the area with the initial occupation and annexation, retreated; those who fell into the German hands were treated harshly, many were executed.

After the war, Narva's inhabitants previously evacuated by the Germans were for the most part not permitted to return and were replaced by refugees and workers administratively mobilized from western Russia, Belarus and Ukraine.[20] By 1989, ethnic Russians made up 30.3% of the population in Estonia.[21]

During the Singing Revolution, the Intermovement, International Movement of the Workers of the ESSR, organised the indigenous Russian resistance to the independence movement and purported to represent the ethnic Russians and other Russophones in Estonia.[22]

In independent Estonia (1990–present)

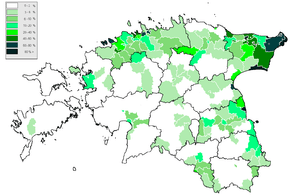

Today most Russians live in Tallinn and the major northeastern cities of Narva, Kohtla-Järve, Jõhvi, and Sillamäe. The rural areas are populated almost entirely by ethnic Estonians, except for Lake Peipus coast, which has a long history of Old Believers communities. In 2011, University of Tartu sociology professor Marju Lauristin found that 21% were successfully integrated, 28% showed partial integration, and 51% were unintegrated or little integrated.[23]

There are efforts by the Estonian government to improve its tie with the Russian community with Prime Minister Jüri Ratas learning Russian to better communicate with them.[24] The younger generation is better integrated with the rest of the country such as joining the military via conscription and improve their Estonian language skills.[24]

Citizenship

The restored republic recognised citizenship only for the pre-occupation citizens or descendants from such (including the long-term Russian settlers from earlier influxes, such as Lake Peipus coast and the 10,000 residents of the Petseri County)[25], rather than to grant Estonian nationality to all Estonian-resident Soviet citizens. The Citizenship Act provides the following requirements for naturalisation of those people who had arrived in the country after 1940,[26] the majority of whom were ethnic Russians: knowledge of the Estonian language, Constitution and a pledge of loyalty to Estonia.[27] The government offers free preparation courses for the examination on the Constitution and the Citizenship Act, and reimburses up to 380 euros for language studies.[28]

Under the law, residents without citizenship may not elect the Riigikogu (the national parliament) nor the European Parliament, but are eligible to vote in the municipal elections.[29] As of 2 July 2010, 84.1% of Estonian residents are Estonian citizens, 8.6% are citizens of other countries (mainly Russia) and 7.3% are "persons with undetermined citizenship".[30]

Between 1992 and 2007 about 147,000 people acquired Estonian or Russian citizenship, or left the country, bringing the proportion of stateless residents from 32% down to about 8 percent.[29] According to Amnesty International's 2015 report, approximately 6.8% of Estonia's population are not citizens of the country.[31]

In late 2014 an amendment to the law was proposed that would give Estonian citizenship to children of non-citizen parents who have resided in Estonia for at least five years.[32]

Language requirements

The perceived difficulty of the language tests became a point of international contention, as the government of the Russian Federation and a number of human rights organizations objected on the grounds that they made it hard for many Russians who had not learned the language to gain the citizenship in the short term. As a result, the tests were altered somewhat, due to which the number of stateless persons steadily decreased. According to Estonian officials, in 1992, 32% of residents lacked any form of citizenship. In May 2009, the Population register reported that 7.6% of residents have undefined citizenship and 8.4% have foreign citizenship, mostly Russian.[33] As the Russian Federation was recognized as the successor state to the Soviet Union, all former USSR citizens qualified for natural-born citizenship of Russia, available upon mere request, as provided by the law "On the RSFSR Citizenship" in force up to the end of 2000.[34]

By county

| County | Russians | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Ida-Viru | 106,664 | 72.8% |

| Harju | 180,477 | 31.3% |

| Tartu | 17,572 | 12.2% |

| Valga | 3,730 | 12.2% |

| Lääne-Viru | 5,472 | 9.6% |

| Pärnu | 6,372 | 8.0% |

| Lääne | 1,851 | 8.0% |

| Jõgeva | 2,126 | 7.0% |

| Rapla | 1,108 | 3.8% |

| Põlva | 1,088 | 3.7% |

| Võru | 1,170 | 3.4% |

| Viljandi | 1,215 | 2.7% |

| Järva | 801 | 2.7% |

| Saare | 284 | 1.0% |

| Hiiu | 58 | 0.7% |

| Total | 324,431 | 25.2%[35] |

Notable Russians from Estonia

- Alexy II of Moscow was born in Tallinn.

- Anna Levandi (née Kondrashova), a former competitive figure skater, silver medalist at the 1984 World Championships, a four-time European bronze medalist

- Valery Karpin, a former football player who represented the Russian national team, was born in Narva. Since 2003 he holds Estonian citizenship.

- Nikolai Stepulov, silver medal in Men's Boxing, lightweight class in the 1936 Summer Olympics.

- Igor Severyanin (Igor Lotaryov), poet; lived, married, and died in Estonia.

- Tanja Mihhailova, represented Estonia in the Eurovision Song Contest 2014.

- Nikolai Novosjolov, Estonian fencer.

- Jevgeni Ossinovski, Estonian politician and former leader of the Estonian Social Democratic Party.

See also

- Baltic Russians

- Ethnic Russians in post-Soviet states

- Demographics of Estonia

References

- Campbell, Lyle (2004). Historical Linguistics. MIT Press. p. 418. ISBN 0-262-53267-0.

- Bojtár, Endre (1999). Foreword to the Past. Central European University Press. p. 88. ISBN 9789639116429.

- Tvauri, Andres (2012). The Migration Period, Pre-Viking Age, and Viking Age in Estonia. pp. 33, 59, 60. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- Miljan, Toivo (13 January 2004). Historical Dictionary of Estonia. ISBN 9780810865716.

- Mäesalu, Ain (2012). "Could Kedipiv in East-Slavonic Chronicles be Keava hill fort?" (PDF). Estonian Journal of Archaeology. 1: 199. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- "Pühtitsa (Pyhtitsa) Dormition Convent". Archived from the original on 20 June 2004.

- Kahk, J.; Palamets, H.; Vahtre, S. (1974), Eesti NSV ajaloost. Lisamaterjali VII-VIII klassi NSV Liidu ajaloo kursuse juurde. 7. trükk, Tallinn: Valgus

- Frucht, Richard (2005). Eastern Europe. ABC-CLIO. p. 65. ISBN 1-57607-800-0.

- Smith, David James (2005). The Baltic States and Their Region. Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-420-1666-8.

- "EESTI - ERINEVATE RAHVUSTE ESINDAJATE KODU" (in Estonian). miksike.ee.

- Suksi, Markku (198). Autonomy. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 253. ISBN 9041105638.

- Kishkovsky, Sophia (6 December 2008). "Patriarch Aleksy II". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 December 2008.

- Mälksoo, Lauri (2003). Illegal Annexation and State Continuity: The Case of the Incorporation of the Baltic States by the USSR. Leiden – Boston: Brill. ISBN 90-411-2177-3.

- Chernichenko, S. V. (August 2004). "Об "оккупации" Прибалтики и нарушении прав русскоязычного населения" (in Russian). Международная жизнь». Archived from the original on 27 August 2009.

- Isakov, S. G. (2005). Очерки истории русской культуры в Эстонии, Изд. : Aleksandra (in Russian). Tallinn. p. 21.

- Chinn, Jeff; Kaiser, Robert John (1996). Russians as the new minority. Westview Press. p. 97. ISBN 0-8133-2248-0.

- Smith, David (2001). Estonia: independence and European integration. Routledge. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-415-26728-1.

- Isakov, S. G. (2005). Очерки истории русской культуры в Эстонии (in Russian). Tallinn. pp. 394–395.

- "Estonian International Commission for Investigation of Crimes Against Humanity" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 June 2007.

- Batt, Judy; Wolczuk, Kataryna (2002). Region, state, and identity in Central and Eastern Europe. Routledge. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-7146-5243-6.

- "Population by Nationality". Estonia.eu.

- Bunce, Valerie; Watts, Steven (2005). "Managing Diversity and Sustaining Democracy: Ethnofederal versus Unitary States in the Postcommunist World". In Philip G. Roeder, Donald Rothchild (ed.). Sustainable peace: power and democracy after civil wars. Cornell University Press. p. 151. ISBN 0801489741.

- Koort, Katja (July 2014). "The Russians of Estonia: Twenty Years After". World Affairs.

- https://www.reuters.com/article/us-baltics-russia/wary-of-divided-loyalties-a-baltic-state-reaches-out-to-its-russians-idUSKBN1630W2

- "Estonian passport holders at risk". The Baltic Times. 21 May 2008. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- Ludwikowski, Rett R. (1996). Constitution-making in the region of former Soviet dominance. Duke University Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-8223-1802-6.

- "Citizenship Act of Estonia". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007.

- "Government to develop activities to decrease the number of non-citizens". Archived from the original on 1 September 2009.

- Puddington, Arch; Piano, Aili; Eiss, Camille; Roylance, Tyler (2007). "Estonia". Freedom in the World: The Annual Survey of Political Rights and Civil Liberties. Freedom House. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 248. ISBN 0-7425-5897-5.

- "Citizenship". Estonia.eu. 13 July 2010. Archived from the original on 27 August 2010. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- "Amnesty International Report 2014/15: The State of the World's Human Rights". amnesty.org. 25 February 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- "Riigikogu asub arutama kodakondsuse andmise lihtsustamist" (in Estonian). 12 November 2014.

- "Estonia: Citizenship". vm.ee. Archived from the original on 11 July 2007.

- Gradirovsky, Sergei. "The Policy of Immigration and Naturalization in Russia: Present State and Prospects" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2008.

- "Population by sex, ethnic nationality and County, 1 January". stat.ee. Statistics Estonia. 1 January 2013. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

Further reading

- "Alternative Report for the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination of United Nations" (PDF).

- "The Russian Diaspora in Latvia and Estonia: Predicting Language Outcomes" (PDF).

- "Report on Estonia". Amnesty International. 2007.

- "Linguistic minorities in Estonia: Discrimination must end". Amnesty International. 7 December 2006.

- Lucas, Edward (14 December 2006). "An excess of conscience – Estonia is right and Amnesty is wrong". The Economist.

- Vetik, Raivo (1993). "Ethnic conflict and accommodation in post-communist Estonia". Journal of Peace Research. 30 (3): 271–280. JSTOR 424806.

- Andersen, Erik André (1997). "The Legal Status of Russians in Estonian Privatisation Legislation 1989–1995". Europe-Asia Studies. 49 (2): 303–316. JSTOR 153989.

- Park, Andrus (1994). "Ethnicity and Independence: The Case of Estonia in Comparative Perspective". Europe-Asia Studies. 46 (1): 69–87. JSTOR 153031.

- Vares, Peeter; Zhurayi, Olga (1998). Estonia and Russia, Estonians and Russians: A Dialogue. 2nd ed. Tallinn: Olof Palme International Center.

- Lauristin, Marju; Heidmets, Mati (2002). The Challenge of the Russian Minority: Emerging Multicultural Democracy in Estonia. Tartu: Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastus.