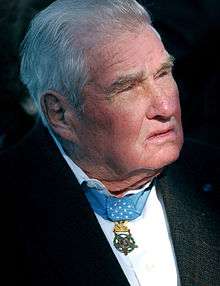

Russell E. Dunham

Russell Dunham (February 23, 1920 – April 6, 2009)[1][2] was an American World War II veteran and recipient of the Medal of Honor. On January 8, 1945, as a member of Company I, 30th Infantry, 3d Infantry Division, Dunham eliminated three German machine gun nests despite being injured himself.

Russell E. Dunham | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | February 23, 1920 East Carondelet, Illinois |

| Died | April 6, 2009 (aged 89) Godfrey, Illinois |

| Place of burial | Valhalla Memorial Park and Mausoleum, Godfrey, Illinois |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/ | United States Army |

| Rank | Technical Sergeant |

| Unit | 3rd Battalion, 30th Infantry, 3d Infantry Division. |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Awards | Medal of Honor Silver Star Bronze Star Croix de Guerre Purple Heart |

Early life

Dunham and his brother Ralph, who also joined him in battle.[3] He joined the Army from Brighton, Illinois in August 1940.[4]

Combat action on January 8, 1945

Dunham was a platoon leader in his unit. Dunham's unit became pinned down at the base of snow-covered Hill 616, a steep hill in Alsace-Lorraine near Kaysersberg, France on January 8, 1945. With machine gun fire coming down the hill in front of their unit, and a heavy artillery barrage landing behind them, Dunham decided "the only way to go was up".[5] Using a white mattress cover as a camouflage aid against the backdrop of the snow, Dunham began moving up the hill. He carried with him a dozen hand grenades and a dozen magazines for his M1 Carbine.

Dunham began crawling more than 100 yards (91 m) to the first machine gun nest under fire from two machine guns and supporting riflemen. When10 yards (9 m) from the nest, he jumped up to assault the nest and was hit by a bullet which caused him to tumble 15 yards (14 m) downhill. He got back up and charged the nest firing his carbine as he went, and kicked aside an egg grenade that had landed at his feet. Prior to reaching the nest, he tossed a hand grenade into the nest. When he got to the nest, he killed the machine gunner and his assistant. His carbine then jammed, and he jumped into the machine gun emplacement. He threw a third German in the nest down the hill who was later captured by his unit.

With his carbine jammed, he picked up another carbine from a wounded soldier and advanced on the second nest, 50 yards (46 m) away. As he came within25 yards (23 m) of the nest, he lobbed two hand grenades into the nest, wiping it out. He followed this up by firing down fox holes used in support of the nest. He then began his slow advance on the third nest, 65 yards (59 m) up the hill. He made his advance on the third nest under heavy automatic fire and grenades. As he came within 15 yards (14 m) of the nest, he tossed more grenades and wiped out the last nest, barely being missed at point blank range by a German rifleman.

During the action, Dunham killed nine Germans, wounded seven and captured two on his own. Nearly 30 other Germans were captured as a result of his actions.

When Dunham was presented with the Medal of Honor, General Alexander Patch said as he placed the award around Dunham's neck that his actions in single-handedly destroying the machine gun nests saved the lives of 120 U.S. soldiers who had been pinned down.

For his injuries on that day, Dunham also received the Purple Heart. Shrapnel from his injuries remained in his body for the rest of his life, and Dunham was quoted as saying "The shrapnel in my leg is a reminder of the war we fought."[6]

Return to the front

Dunham returned to the front before his wounds healed. On January 22 his battalion was surrounded by tanks, forcing most of the men to surrender. The following morning, two German soldiers discovered Dunham hiding in a sauerkraut barrel outside a barn. When their search of his pockets turned up a pack of cigarettes, they fought over it, overlooking his pistol in a shoulder holster. Later that day as he was being transported toward German lines, the driver stopped in a bar, giving Dunham the opportunity to shoot his other captor in the head and set off toward the American lines. Dunham suffered severe frostbite while completing his escape.[7]

Medal of Honor citation

Rank: Technical Sergeant, U.S. Army Organization: Company I, 30th Infantry, 3d Infantry Division. Place: Near Kaysersberg, France, Date: 8 January 1945. Entered service at: Brighton, Illinois Order: G.O. No.: 37, 11 May 1945.

Citation:

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at risk of life above and beyond the call of duty. At about 1430 hours on 8 January 1945, during an attack on Hill 616, near Kayserberg, France, T/Sgt. Dunham single-handedly assaulted 3 enemy machine guns. Wearing a white robe made of a mattress cover, carrying 12 carbine magazines and with a dozen hand grenades snagged in his belt, suspenders, and buttonholes, T/Sgt. Dunham advanced in the attack up a snow-covered hill under fire from 2 machine guns and supporting riflemen. His platoon 35 yards behind him, T/Sgt. Dunham crawled 75 yards under heavy direct fire toward the timbered emplacement shielding the left machine gun. As he jumped to his feet 10 yards from the gun and charged forward, machine gun fire tore through his camouflage robe and a rifle bullet seared a 10-inch gash across his back sending him spinning 15 yards down hill into the snow. When the indomitable sergeant sprang to his feet to renew his 1-man assault, a German egg grenade landed beside him. He kicked it aside, and as it exploded 5 yards away, shot and killed the German machine gunner and assistant gunner. His carbine empty, he jumped into the emplacement and hauled out the third member of the gun crew by the collar. Although his back wound was causing him excruciating pain and blood was seeping through his white coat, T/Sgt. Dunham proceeded 50 yards through a storm of automatic and rifle fire to attack the second machine gun. Twenty-five yards from the emplacement he hurled 2 grenades, destroying the gun and its crew; then fired down into the supporting foxholes with his carbine dispatching and dispersing the enemy riflemen. Although his coat was so thoroughly blood-soaked that he was a conspicuous target against the white landscape, T/Sgt. Dunham again advanced ahead of his platoon in an assault on enemy positions farther up the hill. Coming under machinegun fire from 65 yards to his front, while rifle grenades exploded 10 yards from his position, he hit the ground and crawled forward. At 15 yards range, he jumped to his feet, staggered a few paces toward the timbered machinegun emplacement and killed the crew with hand grenades. An enemy rifleman fired at pointblank range, but missed him. After killing the rifleman, T/Sgt. Dunham drove others from their foxholes with grenades and carbine fire. Killing 9 Germans—wounding 7 and capturing 2—firing about 175 rounds of carbine ammunition, and expending 11 grenades, T/Sgt. Dunham, despite a painful wound, spearheaded a spectacular and successful diversionary attack.[8]

Military awards

| Medal of Honor | |

| Silver Star | |

| Bronze Star | |

| Purple Heart | |

| Croix de Guerre for heroism from the president of France. |

Later life

Dunham and his wife Wilda lived on a small farm near Jerseyville, Illinois for over 30 years.[5] He regularly attended a variety of functions related to honoring Medal of Honor recipients. Dunham erected a monument at Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery in honor of those who served with the 3rd Infantry Division. The monument was dedicated on May 20, 2000, and stands near Flagstaff and Rostrum Drive on the cemetery grounds.[9] In his later years he still enjoyed coon hunting.[5]

Death

Dunham died of heart failure in his sleep on the morning of April 6, 2009 at his home in Godfrey, Illinois at the age of 89.[10] He is interred at Godfrey's Valhalla Memorial Park.[11]

References

- Holley, Joe (April 8, 2009). "Russell Dunham dies at 89; Medal of Honor recipient". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 9, 2009.

- Russell Dunham, awarded Medal of Honor for bravery, dies

- Ande Yakstis, Alton Telegraph staff writer. "World War II Congressional Medal of Honor recipient Technical Sergeant Russell E. Dunham, US Army". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved October 2, 2006.

- WWII Army Enlistment Records

- Ralph Kinney Bennett, Reader's Digest. "The Medal of Honor - Profiles of men who'vereceived the Medal of Honor". Retrieved October 2, 2006.

- Judy Griffin. "Medal of Honor recipient Durham cited in national magazine". Archived from the original on January 8, 2007. Retrieved October 2, 2006.

- RUSSELL DUNHAM, 89, Sergeant Awarded Medal of Honor

- United States Army. "Medal of Honor citation". Retrieved October 2, 2006.

- United States Department of Veterans Affairs. "Burial & Memorials - Cemeteries - Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery". Retrieved October 2, 2006.

- Thorsen, Leah (7 April 2009). "Russell Dunham World War II veteran won Medal of Honor for bravery during battle in France in 1945 OBITUARY". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. STLtoday.com. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- Services Friday for Alton Medal of Honor recipient. Retrieved on April 10, 2009