Runcorn Town Hall

Runcorn Town Hall is in Heath Road, Runcorn, Cheshire, England. It is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a designated Grade II listed building.[1] It was originally built as Halton Grange, a mansion for Thomas Johnson, a local industrialist. After passing through the ownership of two other industrialists, it was purchased in the 1930s by Runcorn Urban District Council and converted into their offices.

| Runcorn Town Hall | |

|---|---|

| Halton Grange | |

Runcorn Town Hall, south aspect, with the newer office block in the background to the right | |

| Location | Heath Road, Runcorn, Cheshire, England |

| Coordinates | 53.3336°N 2.7238°W |

| OS grid reference | SJ 518 820 |

| Built | 1853–56 |

| Built for | Thomas Johnson |

| Architect | Charles Verelst |

| Architectural style(s) | Italianate |

| Governing body | Halton Borough Council |

Listed Building – Grade II | |

| Designated | 31 October 1983 |

| Reference no. | 1104859 |

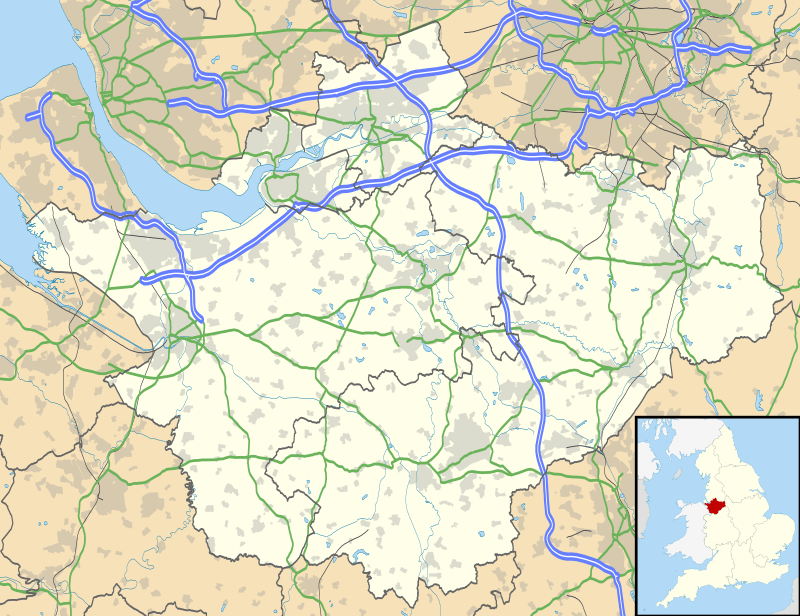

Location in Cheshire | |

History

In January 1854 the land on which the building stands was bought by Thomas Johnson from Francis Selkeld for £4,280 (equivalent to £400,000 in 2019).[2] Thomas was the younger brother in the partnership of John & Thomas Johnson, soap and alkali manufacturers in Runcorn.[3] In 1853–56 a mansion was built for Thomas on the land to a design by Charles Verelst (formerly Reed).[1] The name of the mansion was Halton Grange and its gardens were planned by Edward Kemp.[4] In the 1860s the Johnson brothers became involved in the American Civil War by trying to break a naval blockade at Charleston but all their ships were sunk, resulting in a considerable loss of money. They eventually became bankrupt in 1871.[5] In that year Halton Grange and its surrounding farm were sold to Charles Hazlehurst for £10,428 (equivalent to £980,000 in 2019).[2] Charles Hazlehurst was the junior partner in the other soap and alkali business in Runcorn, Hazlehurst & Sons.[6] Charles died in 1878, leaving Halton Grange to his son, Charles Whiteway Hazlehurst, with a life interest to his wife, Julia, who died in 1903.[7]

In 1904 the house was leased to Francis Boston, the owner of a tannery in Runcorn, who bought it in 1909 for £5,000 (equivalent to £530,000 in 2019).[8] Francis Boston died in 1929 and the house and grounds were put up for auction. In 1931 Frederick Clare and Latham Ryder, local builders, bought part of the grounds for £1,975 (equivalent to £140,000 in 2019).[8] In 1932 Runcorn Urban District Council bought the house and the remainder of the grounds, a total of 11 3⁄4 acres (4.8 ha), for £2,250 (equivalent to £160,000 in 2019).[8][9] The following year the building was converted into the offices of the Runcorn Urban District Council. In 1964–65 an office block was built adjacent to the house and the house was adapted to become the civic suite.[10]

Description

Exterior

The exterior of the building is rendered and the roof is of slate. The building is in two storeys in the style of an Italianate villa, with a belvedere rising to four storeys.[1] The authors of the Buildings of England series suggest it has similarities with Osborne House.[11] The building has three bays on each front. The entrance front has a Tuscan portico with an open balustrade above it. The bay between the portico and the tower has a triple round-headed window with another balustrade above it. All corners have rusticated quoins. The upper level of the tower has triple openings which are flanked by pilasters on all faces. The ground floor windows are double casements and those above are sash windows.[1]

Interior

The ground floor includes the mayor's parlour, a members' room and committee rooms. On the upper floor are reception rooms and a kitchen. A more modern council chamber has been added to the rear. The entrance hall has a mosaic floor, probably by Minton, in the centre of which is the figure of a young girl's head, possibly the daughter of Thomas Johnson. The mayor's parlour has an unusual feature, a window above the fireplace. This is concealed by a mirror which can be slid sideways. The chimney for the fireplace is built into the wall to the right of the window.[10] The staircase is geometrical with cast iron balusters, over which is a large window glazed in a Venetian style.[1] The stained glass in this window depicts Runcorn's coat of arms.[12] On the walls overlooking the staircase are two large paintings by Andrea Casali depicting the Continence of Scipio and Sophonisba taking Poison. These paintings were commissioned in about 1743 by Richard Child, 1st Earl Tylney for Wanstead House. The frames were designed by William Kent.[11][12] In 1822 the paintings were sold, and by 1825 they were hanging in the entrance hall of Eaton Hall. It is likely that they were purchased by Thomas Johnson around the time that the house was built. Elsewhere in the building are other paintings, many of which show Runcorn in former times.[12]

External features

Most of the area occupied by the gardens laid out by Edward Kemp forms a public park. The adjacent office block was reclad and refurbished in 2007. In 2008 a garden was established to the north of the town hall by the town of Tongling in China; it includes a traditional Chinese sculpture depicting acrobats.[11]

References

Citations

- Historic England, "Runcorn Town Hall (1104859)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 12 August 2012

- Anon 1990, p. 1

- Starkey 1990, p. 154

- Kemp 1860, p. 270

- Starkey 1990, p. 158

- Starkey 1990, p. 156

- Anon 1990, p. 5

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017), "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)", MeasuringWorth, retrieved 2 February 2020

- Anon 1990, p. 6

- Anon 1990, p. 13

- Hartwell et al. 2011, p. 561

- Anon 1990, pp. 13–16

Sources

- Anon (1990), Runcorn Town Hall: A History and Description, Halton Borough Council

- Hartwell, Clare; Hyde, Matthew; Hubbard, Edward; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2011) [1971], Cheshire, The Buildings of England, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-17043-6

- Kemp, Edward (1860), How to Lay out a Garden (2nd ed.), New York: John Wiley, p. 270, OCLC 56001631

- Starkey, H. F. (1990), Old Runcorn, Halton Borough Council

Further reading

- de Figueiredo, Peter; Treuherz, Julian (1988), Cheshire Country Houses, Chichester: Phillimore, pp. 235–237, ISBN 0-85033-655-4