Ross Ulbricht

Ross William Ulbricht (born March 27, 1984) is an American convict best known for creating and operating the darknet market website Silk Road from 2011 until his arrest in 2013.[4] The site was designed to use Tor for anonymity and bitcoin as a currency.[5][6] Ulbricht's online pseudonym was "Dread Pirate Roberts" after the fictional character in the novel The Princess Bride and its film adaptation.

Ross Ulbricht | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | March 27, 1984 |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | Dread Pirate Roberts, Frosty, Altoid |

| Citizenship | American |

| Alma mater | University of Texas at Dallas (B.S. 2006) Pennsylvania State University (M.S. 2009) |

| Occupation | Darknet market operator |

| Years active | February 2011 – October 2013 |

| Known for | Creator of Silk Road |

| Net worth | $28.5 million (at time of seizure)[1] |

| Conviction(s) | Money laundering Computer hacking Conspiracy to traffic narcotics (February 6, 2015)[2] |

| Criminal penalty | Double life imprisonment + 40 years without possibility of parole (May 29, 2015) |

Date apprehended | October 1, 2013 |

| Imprisoned at | United States Penitentiary, Tucson[3] |

| Website | https://freeross.org |

In February 2015, Ulbricht was convicted of money laundering, computer hacking, conspiracy to traffic fraudulent identity documents, and conspiracy to traffic narcotics by means of the internet.[7] In May 2015, he was sentenced to a double life sentence plus forty years without the possibility of parole. Ulbricht's appeals to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in 2017 and the U.S Supreme Court in 2018 were unsuccessful.[8][9][10] He is currently incarcerated at the United States Penitentiary in Tucson.[11]

Early life and education

Ulbricht grew up in the Austin metropolitan area. He was a Boy Scout,[12] attaining the rank of Eagle Scout.[13] He attended West Ridge Middle School,[14] and Westlake High School, both near Austin. He graduated from high school in 2002.[15]

He attended the University of Texas at Dallas on a full academic scholarship,[13] and graduated in 2006 with a bachelor's degree in physics.[15] He then attended Pennsylvania State University, where he was in a master's degree program in materials science and engineering and studied crystallography. By the time Ulbricht graduated, he had become interested in libertarian economic theory. In particular, Ulbricht adhered to the political philosophy of Ludwig von Mises, supported Ron Paul, and participated in college debates to discuss his economic views.[14][16]

Ulbricht graduated from Penn State in 2009 and returned to Austin. By this time Ulbricht, finding regular employment unsatisfying, wanted to become an entrepreneur, but his first attempts to start his own business failed. He tried day trading and started a video game company. His mother claimed that his LinkedIn profile referred to a massively multiplayer online role-playing game, not a darknet market, when it stated, "I am creating an economic simulation to give people a first-hand experience of what it would be like to live in a world without the systemic use of force."[17]:7:20 He eventually partnered with his friend Donny Palmertree to help build an online used book seller, Good Wagon Books.

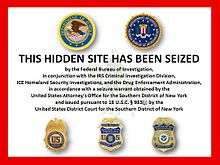

Silk Road, arrest and trial

Silk Road used Tor and bitcoin. Tor is a network which implements protocols that encrypt data and routes internet traffic through intermediary servers that anonymize IP addresses before reaching a final destination. By hosting his market as a Tor site, Ulbricht could conceal its IP address.[5][6] Bitcoin is a cryptocurrency; while all bitcoin transactions are recorded in a log called the blockchain, users who avoid linking their identities to their online "wallets" can conduct transactions with considerable anonymity.[18][19]

Ulbricht used the Dread Pirate Roberts username for Silk Road. However, whether he was the only one to use that account is disputed.[20][21] Dread Pirate Roberts attributed his inspiration for creating the Silk Road marketplace as "Alongside Night and the works of Samuel Edward Konkin III."[22]

Ulbricht began to work on developing his online marketplace in 2010 as a side project to Good Wagon Books. He also sporadically kept a diary during the operating history of Silk Road; in his first entry he outlined his situation prior to launch, and predicted he would make 2011 "a year of prosperity" through his ventures.[14][23] Ulbricht may also have included a reference to Silk Road on his LinkedIn page, where he discussed his wish to "use economic theory as a means to abolish the use of coercion and aggression amongst mankind" and claimed "I am creating an economic simulation to give people a first-hand experience of what it would be like to live in a world without the systemic use of force."[16] Ulbricht moved to San Francisco prior to his arrest.[16]

Ulbricht was first connected to "Dread Pirate Roberts" by Gary Alford, an IRS investigator working with the DEA on the Silk Road case, in mid-2013.[24][25] The connection was made by linking the username "altoid", used during Silk Road's early days to announce the website, and a forum post in which Ulbricht, posting under the nickname "altoid", asked for programming help and gave his email address, which contained his full name.[24] In October 2013, Ulbricht was arrested by the FBI while at the Glen Park branch of the San Francisco Public Library, and accused of being the "mastermind" behind the site.[26][27][28]

To prevent Ulbricht from encrypting or deleting files on the laptop he was using to run the site as he was arrested, two agents pretended to be quarreling lovers. When they had sufficiently distracted him,[29] according to Joshuah Bearman of Wired, a third agent grabbed the laptop while Ulbricht was distracted by the apparent lovers' fight and handed it to agent Thomas Kiernan.[30] Kiernan then inserted a flash drive in one of the laptop's USB ports, with software that copied key files.[29]

On August 21, 2014, Ulbricht was charged with money laundering, conspiracy to commit computer hacking, and conspiracy to traffic narcotics.[31] He was ordered held without bail.[28]

On February 4, 2015, Ulbricht was convicted on all counts after a jury trial that took place in January 2015.[32] On May 29, 2015, he was sentenced to double life imprisonment plus forty years, without the possibility of parole.[33][34]

Federal prosecutors alleged that Ulbricht had paid $730,000 in murder-for-hire deals targeting at least five people,[28] allegedly because they threatened to reveal Ulbricht's Silk Road enterprise.[35][36] Prosecutors believe no contracted killing actually occurred.[28] Ulbricht was not charged in his trial in New York federal court with any murder-for-hire,[28][37] but evidence was introduced at trial supporting the allegations.[28][36] The evidence that Ulbricht had commissioned murders was considered by the judge in sentencing Ulbricht to life, and was a factor in the Second Circuit's decision to affirm the life sentence.[36] A separate indictment against Ulbricht in federal court in Maryland on a single murder-for-hire charge, alleging that he contracted to kill one of his employees (a former Silk Road moderator),[38] was dismissed with prejudice by prosecutors in July 2018, after his New York conviction and sentence became final.[39][40]

After the conviction

Ulbricht appealed his conviction and sentence to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in January 2016, centered on claims that the prosecution illegally withheld evidence of DEA agents' malfeasance in the investigation of Silk Road, for which two agents were convicted.[41] Ulbricht also argued his sentence was too harsh.[42][43] Oral argument was heard in October 2016,[44][36][45] and the Second Circuit issued its decision in May 2017, upholding Ulbricht's conviction and life sentence in an opinion written by Judge Gerard E. Lynch.[36] In a 139-page opinion,[36] the court affirmed the district court's denial of Ulbricht's motion to suppress certain evidence; affirmed the district court's decisions on discovery and the admission of expert testimony; and rejected Ulbricht's argument that a life sentence was procedurally or substantively unreasonable.[36][45]

In December 2017, Ulbricht filed a petition for a writ of certiorari with the United States Supreme Court, asking the Court to hear his appeal on evidentiary and sentencing issues.[46][47] Twenty-one amici filed five amicus curiae briefs in support of Ulbricht, including the National Lawyers Guild, American Black Cross, Reason Foundation, Drug Policy Alliance, and Downsize DC Foundation.[48] The U.S. government filed a response in opposition to Ulbricht's petition.[48][49] On June 28, 2018, the Supreme Court denied the petition, declining to consider Ulbricht's appeal.[50]

In 2019, Ulbricht attempted to vacate his life sentence, based on a claim of ineffective assistance of counsel by his defense lawyers; this attempt was rejected in August 2019.[51]

Incarceration

During his trial, Ulbricht was incarcerated at the Metropolitan Correctional Center, New York. Starting in July 2017, he was held at USP Florence High.[17] His mother Lyn moved to Colorado so she could visit him regularly.[52] Ulbricht has since been transferred to USP Tucson.[53]

Documentaries

Deep Web is a 2015 documentary film chronicling events surrounding Silk Road, bitcoin, and the politics of the dark web, including the trial of Ulbricht. Silk Road – Drugs, Death and the Dark Web is a documentary covering the FBI operation to track down Ulbricht and close Silk Road. The documentary was shown on UK television in 2017 in the BBC Storyville documentary series.[54]

See also

- USBKill, kill switch software created in response to circumstances of Ulbricht's arrest

- Variety Jones and Smedley, pseudonyms of individuals reported to have been closely involved with the founding of the Silk Road

References

- "FBI Says It's Seized $28.5 Million In Bitcoins From Ross Ulbricht, Alleged Owner Of Silk Road". Forbes.com. October 25, 2013. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- https://freeross.org/the-charges/

- "Federal Bureau of Prisons Inmate Locator". Federal Bureau of Prisons. United States Department of Justice. Retrieved January 14, 2018.

BOP Register Number: 18870-111

- Raymond, Nate (February 4, 2015). "Accused Silk Road operator convicted on U.S. drug charges". Reuters. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- Mullin, Joe (May 29, 2015). "Sunk: How Ross Ulbricht ended up in prison for life". Ars Technica. Condé Nast. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- Leger, Donna Leinwand (May 15, 2014). "How FBI brought down cyber-underworld site Silk Road". USA Today. Retrieved December 13, 2015.

- "Jury Verdict". Docket Alarm. Retrieved September 27, 2016.

- "Silk Road founder loses his appeal, will serve a life sentence for online crimes". Techcrunch.com. Retrieved June 1, 2017.

- "Certiorari Denied" (PDF). Supreme Court of the United States. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 29, 2018. Retrieved June 29, 2018.

- "Judgment in a Criminal Case (Sentencing)". Docket Alarm. Retrieved September 27, 2016.

- "Federal Bureau of Prisons Inmate Locator". Federal Bureau of Prisons. United States Department of Justice. Retrieved January 14, 2018.

Register Number: 18870-111

- "Silk Road's Ross Ulbricht: Drug 'kingpin' or 'idealistic' Boy Scout?" CNN/Money. May 28, 2015. Retrieved on June 15, 2015.

- Segal, David. "Eagle Scout. Idealist. Drug Trafficker?" The New York Times. January 18, 2014. Retrieved on June 10, 2015.

- "The Untold Story of Silk Road, Part 1". Wired. April 2015. Retrieved June 9, 2015.

- "Man with Austin ties charged with running vast underground drugs website" (Archive). Austin American-Statesman. October 2, 2013. Retrieved on June 14, 2015.

- Dewey, Caitlin. "Everything we know about Ross Ulbricht, the outdoorsy libertarian behind Silk Road". Washington Post. October 3, 2013. Retrieved on June 15, 2015.

- "Ross Ulbricht Loses His Appeal. Here's What Happens Next". Corbett Report. Retrieved July 12, 2017.

- Popper, Nathaniel (May 24, 2015). ""We are up to something big": Silk Road discovers Bitcoin". Salon. Retrieved December 13, 2015.

- Pagliery, Jose (February 5, 2015). "Bitcoin fallacy led to Silk Road founder's conviction". cnn.com. CNN Money. Retrieved December 13, 2015.

- Greenburg, Andy (February 9, 2015). "Ross Ulbricht Didn't Create Silk Road's Dread Pirate Roberts. This Guy Did". Wired. Retrieved May 5, 2018.

- Koebler, Jason (December 1, 2016). "Someone Accessed Silk Road Operator's Account While Ross Ulbricht Was in Jail". Motherboard. Retrieved May 5, 2018.

- Greenburg, Andy (April 29, 2013). "Collected Quotations Of The Dread Pirate Roberts, Founder Of Underground Drug Site Silk Road And Radical Libertarian". Forbes. Retrieved May 5, 2018.

- Mullin, Joe (January 21, 2015). ""I have secrets": Ross Ulbricht's private journal shows Silk Road's birth". Ars Technica. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- Popper, Nathaniel (December 25, 2015). "The Tax Sleuth Who Took Down a Drug Lord". New York Times. Retrieved December 26, 2015.

- "Silk Road: Google search unmasked Dread Pirate Roberts". BBC News. August 19, 2017. Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- "Dark net marketplace Silk Road 'back online'". BBC. November 6, 2013. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- Mac, Ryan (October 2, 2013). "Who Is Ross Ulbricht? Piecing Together The Life Of The Alleged Libertarian Mastermind Behind Silk Road [Page 2]". Forbes. Retrieved December 19, 2013.

- "Silk Road founder Ross William Ulbricht denied bail". The Guardian. November 21, 2013. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016.

- Bertrand, Natasha (May 29, 2015). "The FBI staged a lovers' fight to catch the kingpin of the web's biggest illegal drug marketplace". Business Insider. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- "Trial Transcript, Day 2, page 856" (PDF). January 21, 2015. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- "Ross Ulbricht Indictment" (PDF). U.S District Court Southern District of New York. February 4, 2014. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- "Accused Silk Road Operator Ross Ulbricht Convicted on All Counts". NBC News. February 4, 2015. Retrieved June 21, 2015.

- Thielman, Sam (May 29, 2015). "Silk Road operator Ross Ulbricht sentenced to life in prison". The Guardian. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- Greenberg, Andy. "After Ross Ulbricht's First NY Court Appearance, His Lawyer Says He's Not The FBI's Dread Pirate Roberts". Forbes. November 7, 2013. Retrieved on June 15, 2015. "Dratel said Ulbricht is now being held at the Metropolitan Detention Center in Brooklyn[...]"

- Alan Klasfeld, Silk Road Murder Threat Shown as Case Nears End, Courthouse News Service (January 29, 2015): "Silk Road founder Ross Ulbricht is not charged with murder-for-hire in his New York trial, but federal prosecutors have long accused him of hiring a hit-man to kill those who threatened his underground online drug empire. Minutes before the second week of Ulbricht's trial ended on Thursday, a jury saw email records supporting this allegation."

- Cassye M. Cole & Harry Sandick, A Long Journey Through "Silk Road" Appeal: Second Circuit Affirms Conviction and Life Sentence of Silk Road Mastermind, Patterson Belknap Webb & Tyler LLP, Lexology, June 8, 2017): "At trial, the government presented evidence that Ulbricht conspired to engage in multiple murders for hire to protect Silk Road's anonymity. Ulbricht was not charged with these offenses. ... At sentencing, in its Pre-Sentence Investigation Report, the U.S. Probation Office referenced the five commissioned murders, as well as six drug-related deaths connected with Silk Road. On May 29, 2015, the district court sentenced Ulbricht to life in prison, pursuant to the Guidelines advisory sentence range, and based on the recommendation of the U.S. Probation Office. ... While the Court recognized that a life sentence for selling drugs was rare and could be considered harsh, the facts of this case involved much more than routine drug dealings—namely that Ulbricht commissioned at least five murders for hire and did not challenge those murders on appeal."

- Patrick Howell O'Neill (October 22, 2014). "The mystery of the disappearing Silk Road murder charges". The Daily Dot.

- Joseph Cox, 'Murdered' Silk Road Employee Sentenced to Time Served, Vice (January 26, 2016).

- Doherty, Brian (July 25, 2018). "Ross Ulbricht's Murder-for-Hire Charges Dropped by U.S. Attorney". Reason.com.

- United States District Court for the District of Maryland. "Motion to Dismiss Indictment and Superseding Indictment".

- Greenberg, Andy (January 12, 2016). "In Silk Road Appeal, Ross Ulbricht's Defense Focuses on Corrupt Feds". Wired. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- Stempel, Jonathan (May 31, 2017). "Silk Road website founder loses appeal of conviction, life sentence". Reuters. Retrieved May 5, 2018.

- https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-cyber-silkroad-idUSKBN18R23A

- Greenberg, Andy (October 6, 2016). "Judges Question Ross Ulbricht's Life Sentence in Silk Road Appeal". Wired. Retrieved October 15, 2016.

- United States v. Ulbricht, 858 F.3d 71 (2d. Cir. 2017)

- "The Supreme Court is Silk Road founder Ross Ulbricht's last hope". VICE News. Retrieved February 24, 2018.

- Ulbricht, Ross (December 22, 2017). "Ulbricht v. U.S." (PDF). SupremeCourt.Gov. Retrieved February 23, 2018.

- "Ulbricht v. United States". SCOTUSblog. Retrieved February 24, 2018.

- Francisco, Noel (March 7, 2018). "Ulbricht v. U.S." (PDF). SupremeCourt.Gov. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- "U.S. Supreme Court turns away Silk Road website founder's appeal". Reuters. June 28, 2018.

- Silk Road mastermind Ross Ulbricht attempts to vacate life sentence

- Mangu-Ward, Katherine (July 2018). "Ross Ulbricht Is Serving a Double Life Sentence". Retrieved December 31, 2018.

- O'Connell, Justin (January 17, 2019). "Silk Road's Ross Ulbricht moved to another high security prison". Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- Gibbings-Jones, Mark (August 21, 2017). "Monday's best TV: Storyville: Silk Road – Drugs, Death and the Dark Web". The Guardian. Retrieved July 10, 2020.

Further reading

- Greenberg, Andy. "Meet The Dread Pirate Roberts, The Man Behind Booming Black Market Drug Website Silk Road". Forbes. August 14, 2013.

- Greenberg, Andy. "An Interview With A Digital Drug Lord: The Silk Road's Dread Pirate Roberts (Q&A)". Forbes. August 14, 2013.

- Howell O’Neill, Patrick. "The mystery of the disappearing Silk Road murder charges". The Daily Dot. October 22, 2014.

- Borders, Max. "Did Dread Pirate Roberts Deserve a Life Sentence?" (Archive) (Opinion). Newsweek. June 1, 2015.

- Bertrand, Natasha. "Eerie diary entries written by the Silk Road founder who just got a life sentence". Business Insider. May 29, 2015.

- Bearman, Joshuah. "Silk Road: The Untold Story" Wired Magazine. April/May 2015.

- Bilton, Nick, American Kingpin, 2017.

- Doherty, Brian. "Ross Ulbricht's Murder-for-Hire Charges Dropped by U.S. Attorney". Reason. July 25, 2018.